Part One Caldwell's Camp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illinois Catholic Historical Review, Volume II Number 3 (1920)

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Loyola University Chicago Archives & Special Illinois Catholic Historical Review Collections 1920 Illinois Catholic Historical Review, Volume II Number 3 (1920) Illinois Catholic Historical Society Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/illinois_catholic_historical_review Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Illinois Catholic Historical Society, "Illinois Catholic Historical Review, Volume II Number 3 (1920)" (1920). Illinois Catholic Historical Review. 3. https://ecommons.luc.edu/illinois_catholic_historical_review/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Loyola University Chicago Archives & Special Collections at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois Catholic Historical Review by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Illinois Catholic Historical Review Volume II JANUARY, 1920 Number 3 CONTENTS Reminiscences of Early Chicago Bedeiia Eehoe Ganaghan The Northeastern Part of the Diocese of St. Louis Under Bishop Rosati Bev. Jolm BotheBsteinei The Irish in Early Illinois Joseph J. Thompson The Chicago Catholic Institute and Chicago Lyceum Jolm Ireland Gallery- Father Saint Cyr, Missionary and Proto-Priest of Modern Chicago The Franciscans in Southern Illinois Bev. Siias Barth, o. F. m. A Link Between East and West Thomas f. Meehan The Beaubiens of Chicago Frank G. Beaubien A National Catholic Historical Society Founded Bishop Duggan and the Chicago Diocese George s. Phillips Catholic Churches and Institutions in Chicago in 1868 George S. Phillips Editorial Comment Annual Meeting of the Illinois Catholic Historical Society Book Reviews Published by the Illinois Catholic Historical Society 617 ASHLAND BLOCK, CHICAGO, ILL. -

War of 1812 Booklist Be Informed • Be Entertained 2013

War of 1812 Booklist Be Informed • Be Entertained 2013 The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and Great Britain from June 18, 1812 through February 18, 1815, in Virginia, Maryland, along the Canadian border, the western frontier, the Gulf Coast, and through naval engagements in the Great Lakes and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In the United States frustrations mounted over British maritime policies, the impressments of Americans into British naval service, the failure of the British to withdraw from American territory along the Great Lakes, their backing of Indians on the frontiers, and their unwillingness to sign commercial agreements favorable to the United States. Thus the United States declared war with Great Britain on June 18, 1812. It ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814, although word of the treaty did not reach America until after the January 8, 1815 Battle of New Orleans. An estimated 70,000 Virginians served during the war. There were some 73 armed encounters with the British that took place in Virginia during the war, and Virginians actively fought in Maryland, Virginia, and Ohio and in naval engagements. The nation’s capitol, strategically located off the Chesapeake Bay, was a prime target for the British, and the coast of Virginia figured prominently in the Atlantic theatre of operations. The War of 1812 helped forge a national identity among the American states and laid the groundwork for a national system of homeland defense and a professional military. For Canadians it also forged a national identity, but as proud British subjects defending their homes against southern invaders. -

The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative Written by Shirley E

THE EMIGRANT MÉTIS OF KANSAS: RETHINKING THE PIONEER NARRATIVE by SHIRLEY E. KASPER B.A., Marshall University, 1971 M.S., University of Kansas, 1984 M.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1998 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2012 This dissertation entitled: The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative written by Shirley E. Kasper has been approved for the Department of History _______________________________________ Dr. Ralph Mann _______________________________________ Dr. Virginia DeJohn Anderson Date: April 13, 2012 The final copy of this dissertation has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii ABSTRACT Kasper, Shirley E. (Ph.D., History) The Emigrant Métis of Kansas: Rethinking the Pioneer Narrative Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Ralph Mann Under the U.S. government’s nineteenth century Indian removal policies, more than ten thousand Eastern Indians, mostly Algonquians from the Great Lakes region, relocated in the 1830s and 1840s beyond the western border of Missouri to what today is the state of Kansas. With them went a number of mixed-race people – the métis, who were born of the fur trade and the interracial unions that it spawned. This dissertation focuses on métis among one emigrant group, the Potawatomi, who removed to a reservation in Kansas that sat directly in the path of the great overland migration to Oregon and California. -

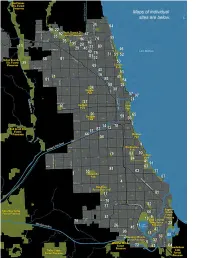

Chicagoâ•Žs Last Unclaimed Indian Territory: a Possible Native

UIC Law Review Volume 50 Issue 1 Article 4 Fall 2016 Chicago’s Last Unclaimed Indian Territory: A Possible Native American Claim Upon Billy Caldwell’s Land, 50 J. Marshall L. Rev. 91 (2016) Scott Priz Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Indigenous, Indian, and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Scott Priz, Chicago’s Last Unclaimed Indian Territory: A Possible Native American Claim Upon Billy Caldwell’s Land, 50 J. Marshall L. Rev. 91 (2016) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol50/iss1/4 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO’S LAST UNCLAIMED INDIAN TERRITORY: A POSSIBLE NATIVE AMERICAN CLAIM UPON BILLY CALDWELL’S LAND SCOTT PRIZ* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 92 II. A BRIEF HISTORY OF BILLY CALDWELL AND HIS LAND ............. 94 A. Billy Caldwell and the Land Granted to Him by Treaty .................................................................................. 94 B. The Land that Was Conveyed and Not Conveyed by Caldwell .............................................................................. 98 C. An Unexpected Son .......................................................... 103 D. Possession of the Land by Robb Robinson -

INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS and TREATIES Vol

INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES Vol. II, Treaties Compiled and edited by Charles J. Kappler. Washington : Government Printing Office, 1904. Home | Disclaimer & Usage | Table of Contents | Index TREATY WITH THE CHIPPEWA, ETC., 1833. Sept. 26, 1833. | 7 Stat., 431. | Proclamation, Feb. 21, 1835. Page Images: 402 | 403 | 404 | 405 | 406 | 407 | 408 | 409 | 410 | 411 | 412 | 413 | 414 | 415 Margin Notes See supplementary articles, post, 410. Lands ceded to United States. Lands west of the Mississippi assigned to the Indians. Moneys to be paid by United States. Fund for the purposes of education, etc. Annuities. Payments for sections of land. Where annuities shall be paid. Treaty binding when ratified. Goods purchased and delivered. Cession of land to United States. Chiefs and headmen parties to treaty. Moneys to be paid for lands relinquished. Goods, provisions, etc. Annuities. Indians to remove in three years. Obligatory when ratified. Page 402 Articles of a treaty made at Chicago, in the State of Illinois, on the twenty-sixth day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and thirty-three, between George B. Porter, Thomas J. V. Owen and William Weatherford, Commissioners on the part of the United States of the one part, and the United Nation of Chippewa, Ottowa and Potawatamie Indians of the other part, being fully represented by the Chiefs and Head-men whose names are hereunto subscribed—which Treaty is in the following words, to wit: ARTICLE 1. The said United Nation of Chippewa, Ottowa, and Potawatamie Indians, cede to the United States all their land, along the western shore of Lake Michigan, and between this Lake and the land ceded to the United States by the Winnebago nation, at the treaty of Fort Armstrong made on the 15th September 1832—bounded on the north by the country lately ceded by the Menominees, and on the south by the country ceded at the treaty of Prairie du Chien made on the 29th July 1829—supposed to contain about five millions of acres. -

Chicago Streets

Chicago Streets Avenue - Title applied mostly to streets running North and South. There are exceptions. Blvd - Title given to streets where trucks over 5 tons are not permitted. Court - Title given to short roadway. Parkway - Title given to street that ends at a park. Place - Title given to street running the 1/2 block between streets. Street - Title applied mostly to streets running East and West. There are exceptions. The information regarding Street changes was complied by William Martin in 1948. A -A Avenue 11400 to 11950S, State Line Road -A Street 1400 to 1500W, Shakespeare -A Street 800 to 999W, 35th Place Abbott Ave., 206W pvt 9050 to 9100S. Named after Robert S. Abbott 1870-1940 was a black lawyer and founder of the Defender Newspaper 1905. At one time street went 8900S to 9500S. -Abbott Ct., Orchard St., 2800 to 3199N 700W. -Aberdeen Ave., 8700 to 944S Aberdeen St. -Aberdeen Ave., 13200 to 13400S Buffalo Ave. Aberdeen St., 1100W 1-12285S and 1-734N. Named after Aberdeen, Scotland which means silver city by the sea. Austin St., Berdeen St., Blackwell St., Bruner Ave., Byer Ave., Curtis St., Dyet St., Dobbins Ave., Grand Ave., High St., Julius St., Lee Ave., Margaret St., Mossprat St., Musprat St., Solon St. -Aberdeen St., 10500 to 10700S Carpenter St. -Aberdeen St., 900 to 1400W Winona St. Academy Court, 812W 100S to 100N. No history for street, but is narrowest street. A mere ten feet wide. Alley -Academy Pl., 810W 100N to 100S. -Achsah Bond Dr., 1325S 600 to 850E. Named after the wife of the first governor of Illinois. -

HSPC July 2008

Member Journal December 2014 A Council Bluffs Christmas Volunteers were all set to return the materials from the Society's History Out of the Vault program N ovem- ber 2nd to the archives when president Mariel Wagner said, "Not so fast!" The exhibit was so well attended she decided to repeat it next month, adding a holiday twist as well. Saturday, December 13, the updated display will bring a touch of Christmas and Council Bluffs memo- ries to a special exhibit from 12:30-3:30 at The Center, 714 South Main Street. Displays will highlight the city through the 20th Century including Christmas post- cards, before and after urban renewal photos, the glory days of parks including Manawa and Fairmount, the first MASH unit (Mobile Hospital #1) which was mustered in Council Bluffs, the city’s radio firsts (KOIL, Sweet 98, Iowa’s first FM), local school histories, and a continuous "Then and Now" video. Bring your camera to get a picture with Mrs. Claus. Dr. Richard Warner and Ryan Roenfeld will be on hand to sign their new local history book, Images of America: Council Bluffs which will make an excellent Christmas gift for anyone on your list who ever lived in Council Bluffs. There will also be a bake sale and other local books and gifts available for purchase. The event The Historical Society of is free and open to the public. You can Pottawattamie County thanks find more information about the event at (Top) Undated photo of Beno's at our corporate members: Christmas. (Lower) Guests examine the www.HistoricalSocietyEvents.com. -

Simon Pokagon – I Write from Quite a Distance from This Man

Chicago’s First Urban Indians – the Potawatomi by John N. Low A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Gregory E. Dowd (Chair) Professor Philip J. Deloria Professor Raymond A. Silverman Associate Professor Vicente M. Diaz © John N. Low ________________________________________________________________________ 2011 Dedication To Irving (Hap) McCue and Daniel (Danny) Rapp – two elders who taught me more than they ever realized; and to my parents, Wilma and Joseph, who gave me opportunity. ii Acknowledgements Every book has many authors and the same is true for this dissertation. I am indebted to many individuals, institutions, and communities for making my work possible. I owe much to the Williams/Daugherty family who made their grandfather’s papers available to me. I am also grateful for the kind assistance from the staffs at the Chicago History Museum archives, the special collections at the Clarke Memorial Library at Central Michigan University, Western Michigan University, the Rackham Graduate Library and the Bentley Library at the University of Michigan, the Harold Washington Library in Chicago, the Grand Rapids Public Museum, the Logan Museum at Beloit College, the Chicago American Indian Center, the Regenstein Library at the University of Chicago, the D’Arcy McNickle Center and special collections at the Newberry Library in Chicago, Pokagon State Park, and the Great Lakes Regional Branch of the National Archives. I also substantially benefitted from the financial support afforded by the award of a five year Rackham Merit Fellowship at the University of Michigan – without which I could not have pursued my dream of returning to academia. -

115 W. Glover St.—Ottawa, IL 61350—Tel. (815) 433-5261 JULY/AUGUST 2012 GUILD HOURS M

The LaSalle County Genealogy Guild – 115 W. Glover St.—Ottawa, IL 61350—Tel. (815) 433-5261 JULY/AUGUST 2012 GUILD HOURS JULY MEETING Mondays & Saturdays Saturday, 21 July 2012 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Meetings—3rd Saturday of Month The speaker for our July meeting will be At 1:00 p.m. GERALD HUSLANDER. His program is 115 W. Glover St., Ottawa titled “Early Settlers of Brookfield Township and the Gallaway Cemetery.” Gerald is the INTERNET CORNER Director of the LaSalle County Historical Soci- The LSCGG’s Home Page address is: ety Utica Museum. Lscgg.org LSCGG’s e-mail address: Brookfield Township [email protected] If you are a member and have not given AUGUST MEETING us your e-mail address, please do so Saturday, 18 August, 2012 at the above address. CHARLES “CHUCK” SANDERS and DAVE OFFICERS MUMPER will present our program this month. They President: Jenan Jobst will be talking about “Letters of the (815) 433-2919 Civil War and the Area.” They will Vice President: Margaret Clemens also speak about General Wallace. (815) 434-6342 Co-Secretaries: Barb Halsey & Sandy Vahl Editor: Carole Nagle PRESIDENT’S LETTER Welcome Summer, We have had some visitors from out of state lately so the researchers are traveling again. We are working on the 1940 census for Illinois. I have done over 40 pages now and finally I got some Ottawa pages. They were fun to do as I knew some of the people and I could use the city directory if I got stuck on a name. -

EARLY DAYS at COUNCIL BLUFFS: Longitude And

Class Rook Ud\. Gop>iiglit]^^_ COPYRIGHT DEPOSrr. EARLY DAYS AT COUNCIL BLUFFS By CHARLES H. BABBITT ILLUSTRATED ''All that I know is, that the facts I state Are true, as Truth has ever been of late. — Byron WASHINGTON, D. C. PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS 1910 copyeioht 1916 By Charles H. Babbitt DEC 916 ©CI,A453043 ;; CONTENTS Pages INTRODUCTION : Wlierefore and How 5—6 EARLY DAYS AT COUNCIL BLUFFS: Longitude and Latitude ; First Occupancy ; Origin of Name ; Hart 's Cut-Off ; Hart 's Bluff ; Bloomer and Gue Histories De Smet's Letter to Jones; Hart's Trapping Station; Who was Hart ? Pottawattamie Indians Arrive ; Old Blockhouse; Billy Caldwell's Village; Jesuit Mission; Fort Croghan; Camp Kearney; Mormons; Miller's Hollow ; Kanesville ; Colonel Kane ; Mormon Church Reorganization ; President Chosen ; General G. M. Dodge; United States Land Office; First "Gentile" Church Edifice; Named Council Bluffs; City Incor- poration ; Townsite Entry ; Survey of Townsite ; News- 9 papers : First Dramatic Performance —24 POTTAWATTAMIE INDIANS: United States Acquire Land in Iowa and Missouri ; Indian Cessions in Illinois and Indiana; Removal of Pottawattamies ; Errone- ously Located; Platte Purchase; Arrival in Iowa; Number Removed ; Blockhouse Erected ; Dr. Edwin James ; Iowa Lands Described ; Father De Smet ; His Mission; Early Writers Err; Old Indian (Wicks) Mill; Historical Works; Colonel Kearney; Sub- Agency Locations ; Camp Fenwick ; Fort Croghan Pottawattamies Relinquish Iowa Lands; Indian and Mormon Co-Occupancy; Departure of Pottawat- tamies 25—40 THE OLD BLOCKHOUSE: Subject of Surmise; Writer's Memory Concerning; Bloomer's Description; Gue's History; Field and Reed History; H. H. Field's Per- sonal Recollection ; Spencer Smith 's Memory ; Ephraim Huntington's Remembrance; Henry De Long's De- scription; Appearance in 1846; Fort Croghan 's Rela- tion; De Smet's Barometric Reading; Nicollett and Fremont's Visit; Camp Kearney; War Department Memorandum; Official Records; When Erected; Jesuit Mission Established ; Mission Abandoned ; Com- ment on Memory ./ . -

The United States' Indian Allies in the Black

FRIENDS LIKE THESE: THE UNITED STATES’ INDIAN ALLIES IN THE BLACK HAWK WAR, 1832 by John William Hall A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Advisor: R. Don Higginbotham Reader: Joseph T. Glatthaar Reader: Michael D. Green Reader: Richard H. Kohn Reader: Theda Perdue © 2007 John William Hall ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JOHN W. HALL: Friends Like These: The United States’ Indian Allies in the Black Hawk War, 1832 (Under the direction of R. Don Higginbotham.) “Friends Like These” examines the decision by elements of the Menominee, Dakota, Potawatomi, and Ho Chunk tribes to ally with the United States government during the Black Hawk War of 1832. Because this conflict is usually depicted as a land- grab by ravenous settlers and the war occurred within two years of the passage of the Indian Removal Act, the military participation of these tribes seems incongruous. This work seeks to determine why various bands of these tribes cooperated with the U.S. Army when such alliance seemed inimical to the interests of their respective tribes. Moreover, it explores the extent to which the Americans conceived of themselves as allies to the Indians while assessing the consequences of this alliance for each of the tribes involved. This study finds that the Indians participated in the Black Hawk War to fulfill their own wartime objectives, and that in so doing they sought to apply familiar forms to the new situation that unfolded in the years after the War of 1812. -

Microsoft Photo Editor

GOOSE ISLAND OVERLOOK This property was once used as a coal storage yard and boat yard prior to its acquisition by the Site No 01 City of Chicago in 2003 thanks to a grant funded by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. The large crane and other structures on the prop- erty are in the process of being removed. The river bank will be graded and the concrete removed. The Chicago Park District will be the eventual owner of the property after the clean-up is completed. Designs are not completed, but improvement of natural habitat will be a strong component within the plan. There will also be a water access point for canoes and kayaks. The park will be used primarily for passive recreation. ARMITAGE C LY KENN B E O L U S RN EDY T O N NORTH DAMEN ASHLAND HALSTED DIVISION Chica go River CHICAGO M ILWA U K E GRAND E KINZIE 1200 NORTH / 1100 WEST OGDEN Goose Island Overlook O . 01 N ADDRESS 1200 N Elston Ave OWNER City of Chicago ACREAGE 1.65 HABITATS 1 Riparian/Water Edge Goose Island Overlook N BR DIRECTIONS Park at 1111 N. Elston; ANC the site is visible through EL S H the fence, or walk out TO CHICAGO onto the Division Street N bridge and view it from RIV the river side. ER Chicago Habitat Directory 2005 58 Page Page 58 100 Feet Riverdale Bend Woods goes for almost a mile The Major Taylor Trail goes through the western RIVERDALE BEND WOODS along the Little Calumet River, and in some places part of the site connecting the Forest Preserve is quite wide, making it a valuable green corridor.