The Good, the Bad and the Ugly Three Cases in the House of Ptolemy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cleopatra II and III: the Queens of Ptolemy VI and VIII As Guarantors of Kingship and Rivals for Power

Originalveröffentlichung in: Andrea Jördens, Joachim Friedrich Quack (Hg.), Ägypten zwischen innerem Zwist und äußerem Druck. Die Zeit Ptolemaios’ VI. bis VIII. Internationales Symposion Heidelberg 16.-19.9.2007 (Philippika 45), Wiesbaden 2011, S. 58–76 Cleopatra II and III: The queens of Ptolemy VI and VIII as guarantors of kingship and rivals for power Martina Minas-Nerpel Introduction The second half of the Ptolemaic period was marked by power struggles not only among the male rulers of the dynasty, but also among its female members. Starting with Arsinoe II, the Ptolemaic queens had always been powerful and strong-willed and had been a decisive factor in domestic policy. From the death of Ptolemy V Epiphanes onwards, the queens controlled the political developments in Egypt to a still greater extent. Cleopatra II and especially Cleopatra III became all-dominant, in politics and in the ruler-cult, and they were often depicted in Egyptian temple- reliefs—more often than any of her dynastic predecessors and successors. Mother and/or daughter reigned with Ptolemy VI Philometor to Ptolemy X Alexander I, from 175 to 101 BC, that is, for a quarter of the entire Ptolemaic period. Egyptian queenship was complementary to kingship, both in dynastic and Ptolemaic Egypt: No queen could exist without a king, but at the same time the queen was a necessary component of kingship. According to Lana Troy, the pattern of Egyptian queenship “reflects the interaction of male and female as dualistic elements of the creative dynamics ”.1 The king and the queen functioned as the basic duality through which regeneration of the creative power of the kingship was accomplished. -

Tomasz Grabowski Jagiellonian University, Kraków*

ELECTRUM * Vol. 21 (2014): 21–41 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.14.001.2778 www.ejournals.eu/electrum THE CULT OF THE PTOLEMIES IN THE AEGEAN IN THE 3RD CENTURY BC Tomasz Grabowski Jagiellonian University, Kraków* Abstract: The cult of the Ptolemies spread in various ways. Apart from the Lagids, the initiative came from poleis themselves; private cult was also very important. The ruler cult, both that organ- ised directly by the Ptolemaic authorities and that established by poleis, was tangibly benefi cial for the Ptolemaic foreign policy. The dynastic cult became one of the basic instruments of political activity in the region, alongside acts of euergetism. It seems that Ptolemy II played the biggest role in introducing the ruler cult as a foreign policy measure. He was probably responsible for bringing his father’s nickname Soter to prominence. He also played the decisive role in popularising the cult of Arsinoe II, emphasising her role as protector of sailors and guarantor of the monarchy’s prosperity and linking her to cults accentuating the warrior nature of female deities. Ptolemy II also used dynastic festivals as vehicles of dynastic propaganda and ideology and a means to popu- larise the cult. The ruler cult became one of the means of communication between the subordinate cities and the Ptolemies. It also turned out to be an important platform in contacts with the poleis which were loosely or not at all subjugated by the Lagids. The establishment of divine honours for the Ptolemies by a polis facilitated closer relations and created a friendly atmosphere and a certain emotional bond. -

The Influence of Achaemenid Persia on Fourth-Century and Early Hellenistic Greek Tyranny

THE INFLUENCE OF ACHAEMENID PERSIA ON FOURTH-CENTURY AND EARLY HELLENISTIC GREEK TYRANNY Miles Lester-Pearson A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11826 This item is protected by original copyright The influence of Achaemenid Persia on fourth-century and early Hellenistic Greek tyranny Miles Lester-Pearson This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews Submitted February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Miles Lester-Pearson, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2015. Date: Signature of Candidate: 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

D'olbia À Tanaïs

D’Olbia à Tanaïs Christel Müller, ancienne élève de l’École Normale Supérieure et ancien membre de l’École Française d’Athènes, est Profes- seur d’histoire grecque à l’Uni- versité de Reims. Ausonius Éditions — Scripta Antiqua 28 — D’Olbia à Tanaïs Territoires et réseaux d’échanges dans la mer Noire septentrionale aux époques classique et hellénistique par Christel MÜLLER Diffusion De Boccard 11 rue de Médicis F - 75006 Paris — Bordeaux 2010 — AUSONIUS Maison de l’Archéologie F - 33607 Pessac cedex http://ausonius.u-bordeaux3.fr/EditionsAusonius Diffusion De Boccard 11 rue de Médicis 75006 Paris http://www.deboccard.com Directeur des Publications : Jérôme France Secrétaire des Publications : Stéphanie Vincent Graphisme de Couverture : Stéphanie Vincent © AUSONIUS 2010 ISSN : 1298-1990 ISBN : 978-2-35613-035-8 Achevé d’imprimer sur les presses de l’imprimerie BM Z.I. de Canéjan 14, rue Pierre Paul de Riquet F - 33610 Canéjan septembre 2010 Illustration de couverture : carte du Bosphore cimmérien (P. Dubrux, pas après 1833, d’après Tunkina 2002, fig. 45) et décret d’Olbia en l’honneur de deux Athéniens vers 340-330 a.C. (d’après I.Olb 5). Pour Graham et Arthur Sommaire Avant-propos 11 Introduction 15 I - Territoires et conquêtes dans le Pont Nord du dernier tiers du ve s. au début du iiie s. a.C. 23 Le Bosphore cimmérien 23 Des Arkhéanaktides aux Spartocides 24 L’intégration de Nymphaion 24 Les cités du Bosphore asiatique 25 La prise de Théodosia 26 La conquête de la Sindikè 31 Colonisation interne : fondations et refondations du Bosphore asiatique 34 Tanaïs, colonie bosporane ? 37 Ethnicité et partage du territoire : archontes des cités et rois des ethnè 39 Le Bosphore cimmérien : représentations et réalités d’une totalité territoriale 41 Marqueurs symboliques et physiques du territoire 43 Et les kourganes ? 46 Olbia pontique 48 Le nom de la cité 48 Situation territoriale d’Olbia à partir du ve s. -

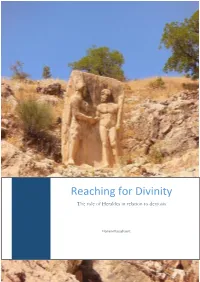

Reaching for Divinity the Role of Herakles in Relation to Dexiosis

Reaching for Divinity The role of Herakles in relation to dexiosis Florien Plasschaert Utrecht University RMA ANCIENT, MEDIEVAL, AND RENAISSANCE STUDIES thesis under the supervision of dr. R. Strootman | prof. L.V. Rutgers Cover Photo: Dexiosis relief of Antiochos I of Kommagene with Herakles at Arsameia on the Nymphaion. Photograph by Stefano Caneva, distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license. 1 Reaching for Divinity The role of Herakles in relation to dexiosis Florien Plasschaert Utrecht 2017 2 Acknowledgements The completion of this master thesis would not have been possible were not it for the advice, input and support of several individuals. First of all, I owe a lot of gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Rolf Strootman, whose lectures not only inspired the subject for this thesis, but whose door was always open in case I needed advice or felt the need to discuss complex topics. With his incredible amount of knowledge on the Hellenistic Period provided me with valuable insights, yet always encouraged me to follow my own view on things. Over the course of this study, there were several people along the way who helped immensely by providing information, even if it was not yet published. Firstly, Prof. Dr. Miguel John Versluys, who was kind enough to send his forthcoming book on Nemrud Dagh, an important contribution to the information on Antiochos I of Kommagene. Secondly, Prof. Dr. Panagiotis Iossif who even managed to send several articles in the nick of time to help my thesis. Lastly, the National Numismatic Collection department of the Nederlandse Bank, to whom I own gratitude for sending several scans of Hellenistic coins. -

Iranians and Greeks in South Russia (Ancient History and Archaeology)

%- IRANIANS & GREEKS IN SOUTH RUSSIA BY M- ROSTOVTZEFF, Hon. D.Litt. PROFESSOR IN THE UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN MEMBER OF THE RUSSIAN ACAPEMY OF SCIENCE I i *&&* OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1922 Oxford University Press London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen Nets York Toronto Melbourne Cape T&tm Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai Humphrey Milford Publisher to the University PREFACE THIS book is not intended to compete with the valuable and learned book of Ellis H. Minns on the same subject. Our aims are different. Minns endeavoured to give a complete survey of the material illustrating the early history of South Russia and of the views expressed by both Russian and non-Russian scholars on the many and various questions suggested by the study of that material. I do not mean that Minns' book is a mere compendium. In dealing with the various problems of the history and archaeology of South Russia Minns went his own way ; his criticism is acute, his views independent. Nevertheless his main object was to give a survey as full and as complete as possible. And his attempt was success- ful. Minns* book will remain for decades the chief source of informa- tion about South Russia both for Russian and for non- Russian scholars. My own aim is different. In my short exposition I have tried to give a history of the South Russian lands in the prehistoric, the proto- historic, and the classic periods down to the epoch of the migrations. By history I mean not a repetition of the scanty evidence preserved by the classical writers and illustrated by the archaeological material but an attempt to define the part played by South Russia in the history of the world in general, and to emphasize the contributions of South Russia to the civilization of mankind. -

The Ptolemies: an Unloved and Unknown Dynasty. Contributions to a Different Perspective and Approach

THE PTOLEMIES: AN UNLOVED AND UNKNOWN DYNASTY. CONTRIBUTIONS TO A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE AND APPROACH JOSÉ DAS CANDEIAS SALES Universidade Aberta. Centro de História (University of Lisbon). Abstract: The fifteen Ptolemies that sat on the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (the date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII) are in most cases little known and, even in its most recognised bibliography, their work has been somewhat overlooked, unappreciated. Although boisterous and sometimes unloved, with the tumultuous and dissolute lives, their unbridled and unrepressed ambitions, the intrigues, the betrayals, the fratricides and the crimes that the members of this dynasty encouraged and practiced, the Ptolemies changed the Egyptian life in some aspects and were responsible for the last Pharaonic monuments which were left us, some of them still considered true masterpieces of Egyptian greatness. The Ptolemaic Period was indeed a paradoxical moment in the History of ancient Egypt, as it was with a genetically foreign dynasty (traditions, language, religion and culture) that the country, with its capital in Alexandria, met a considerable economic prosperity, a significant political and military power and an intense intellectual activity, and finally became part of the world and Mediterranean culture. The fifteen Ptolemies that succeeded to the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII), after Alexander’s death and the division of his empire, are, in most cases, very poorly understood by the public and even in the literature on the topic. -

The Circulation of Ptolemaic Silver in Seleucid Coele Syria and Phoenicia from Antiochus Iii to the Maccabean Revolt: Monetary Policies and Political Consequences

ELECTRUM * Vol. 26 (2019): 9–23 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.19.001.11204 www.ejournals.eu/electrum THE CIRCULatION OF PtoLEMAIC SILVER IN SELEUCID COELE SYRIA AND PHOENICIA FROM ANTIOCHUS III to THE MACCABEAN REVOLT: MonetaRY POLICIES AND POLITICAL CONSEQUENCES Catharine Lorber Abstract: This paper examines the circulation of Ptolemaic silver in the closed monetary zone of Seleucid Coele Syria and Phoenicia. No new silver coinage entered the zone under Antiochus III and Seleucus IV, though hoards were deposited in the Transjordan and eastern Judah in the early years of Antiochus IV. Trade between Phoenicia and Egypt is excluded as an explanatory factor, but the patterns are consistent with Josephus’ account of the dowry of Cleopatra I and Tobiad tax farming. In the 160s BCE fresh Ptolemaic silver began to enter the closed monetary zone, with the earliest finds in Judah, Samaria, and “southern Palestine.” This new influx, like the didrachms “of an uncertain era,” may represent a subsidy from Ptolemy VI to the Maccabees and other dissidents from Seleucid rule. Keywords: closed monetary zone, Ptolemaic silver coinage, dowry, Tobiad, tax farming, Judah, Antiochus III, Antiochus IV, Ptolemy V, Ptolemy VI. When Antiochus III seized Phoenicia and Palestine from Ptolemy V, the region com- prised a closed monetary zone in which Ptolemaic coinage was the sole legal tender. Somewhat surprisingly, Antiochus III maintained the closed monetary zone for precious metal coinage, which in practice meant silver coinage. This curious situation was de- fined by Georges Le Rider in 1995 through the study of coin hoards.1 The hoards reveal that for nearly half a century the only silver coinage circulating in Seleucid Coele Syria and Phoenicia was Ptolemaic. -

Études Pontiques Histoire, Historiographie Et Sites Archéologiques Du Bassin De La Mer Noire

Études de lettres 1-2 | 2012 Études pontiques Histoire, historiographie et sites archéologiques du bassin de la mer Noire Pascal Burgunder (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/edl/283 DOI : 10.4000/edl.283 ISSN : 2296-5084 Éditeur Université de Lausanne Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 mai 2012 ISBN : 978-2-940331-27-7 ISSN : 0014-2026 Référence électronique Pascal Burgunder (dir.), Études de lettres, 1-2 | 2012, « Études pontiques » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 15 mai 2015, consulté le 18 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/edl/283 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/edl.283 © Études de lettres Etudes pontiques Histoire, historiographie et sites archéologiques du bassin de la mer Noire ETUDES DE LETTRES no 290 Revue de la Faculté des lettres de l’Université de Lausanne fondée en 1926 par la Société des Etudes de Lettres Comité de rédaction Alain Corbellari, président Martine Hennard Dutheil de la Rochère Simone Albonico Dave Lüthi Danielle Chaperon François Vallotton Ute Heidmann Rédaction Administration Florence Bertholet Etudes de Lettres Catherine Chène Secrétariat Revue Etudes de Lettres de la Faculté des lettres Bâtiment Anthropole Bâtiment Anthropole CH-1015 Lausanne CH-1015 Lausanne Tél. +41 (21) 692 29 07 Tél. +41 (21) 692 29 09 Courriel : [email protected] Fax. +41 (21) 692 29 05 Site web : www.unil.ch/edl Courriel : [email protected] Abonnement annuel (4 numéros) Frais de port Plein tarif : 60 CHF Suisse : 9 CHF Allemagne : 18 CHF Tarif étudiant : 45 CHF Europe : 21 CHF Autres pays : 26 CHF Prix des volumes Volume simple : 22 CHF (plein tarif) / 20 CHF (prix étudiant) Volume double : 30 CHF (plein tarif) / 26 CHF (prix étudiant) Les volumes de plus de dix ans sont vendus 5 CHF. -

473 Appendix 3A, VI, Attachment 6 DESCENDANCIES PTOLEMAIC

Appendix 3A, VI, Attachment 6 DESCENDANCIES PTOLEMAIC MONARCHS/RELATIVES Ptolemy II Philadelphus to Ptolemy VIII Physcon Refer to prefaces of Attachments 4 and 5 for source information, manners of identification, etc. (1) Resumed from Appendix 3A, VI, Attachment 4, B(6). Ptolemy II Philadelphus / + ? / + ? / + Arsinoe [#3] (3A,VI,Att.4,C(1)/ / + Arsinoe [#2] (3A,VI,Att.4,C(1) / / / / / -- Berenice [II] Ptolemy III a Son a Son Berenice IV + Antiochus II Euergetes (3A,VI,Att. 5(1) / + Berenice IV / + Berenice III (3A,VI,Att.4,B(6) / + ? / + ? / or + Agathocleia / Queen of Cyrene a Son-- a Daughter-- / ? “Brother,” “Sister,” Ptolemy IV Philopater undesignated, undesignated, Continued in part (2) -----------of Ptolemy IV------------ Ptolemy II ultimately succeeded Ptolemy I--who “died in the 84th year of his age, after a reign of 39 years, about 284 years before Christ”--when Ptolemy Ceraunus of Macedon (son of Ptolemy I by Eurydice #3), was unable to mount the Egyptian throne. L 511; 3A, VI, Attachment 4, C(6) and narrative E. “Laodike [Laodice #2], wife of Antiochos II [Attachment 5, (1)] was divorced by him in 252 in order to marry Berenike [Berenice II], daughter of Ptolemais II, a marriage that appears to have been one of the conditions for ending the Second Syrian War.” Burstein, p. 32, fn. 2. (After a revolt by Ptolemy II’s [half-] “brother [by the same mother] Magas, king of Cyrene, which had been kindled by Antiochus [II] the Syrian king,” there was “re-established peace for some time in the family of Philadelphus. Antiochus [II]...married Berenice [II] the daughter of Ptolemy [II]. -

The Jews in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt

Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum herausgegeben von Martin Hengel und Peter Schäfer 7 The Jews in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt The Struggle for Equal Rights by Aryeh Kasher J. C. B. Möhr (Paul Siebeck) Tübingen Revised and translated from the Hebrew original: rponm fl'taDij'jnn DnSQ HliT DDTlinsT 'jp Dpanaa (= Publications of the Diaspora Research Institute and the Haim Rosenberg School of Jewish Studies, edited by Shlomo Simonsohn, Book 23). Tel Aviv University 1978. CIP-Kurztitelaufnahme der Deutschen Bibliothek Kasher, Aryeh: The Jews in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt: the struggle for equal rights / Aryeh Kasher. - Tübingen: Mohr, 1985. (Texte und Studien zum antiken Judentum; 7) ISBN 3-16-144829-4 NE: GT First Hebrew edition 1978 Revised English edition 1985 © J. C. B. Möhr (Paul Siebeck) Tübingen 1985. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. / All rights reserved. Printed in Germany. Säurefreies Papier von Scheufeien, Lenningen. Typeset: Sam Boyd Enterprise, Singapore. Offsetdruck: Guide-Druck GmbH, Tübingen. Einband: Heinr. Koch, Tübingen. In memory of my parents Maniya and Joseph Kasher Preface The Jewish Diaspora has been part and parcel of Jewish history since its earliest days. The desire of the Jews to maintain their na- tional and religious identity, when scattered among the nations, finds its actual expression in self organization, which has served to a ram- part against external influence. The dispersion of the people in modern times has become one of its unique characteristics. Things were different in classical period, and especially in the Hellenistic period, following the conquests of Alexander the Great, when disper- sion and segregational organization were by no means an exceptional phenomenon, as revealed by a close examination of the history of other nations. -

Ptolemaic Pharaohs of Egypt Ptolemy Ii

THE MARION COUNTY MANNA PROJECT offers Commentary on the PTOLEMAIC PHARAOHS OF EGYPT PTOLEMY II Listed on page 2 are the Pharaohs of the Ptolemaic Dynasty (regnal dates are approximate). Subse- quent to the death of Alexander the Great (1) in 323 BC, they ruled Egypt (2) from 305 BC until 30 BC, when they were conquered by the Roman Republic (3) just prior to the founding of the Roman Empire in 27 BC. The Septuagint (LXX) (4), the Greek translation of the Old Testament (5), was written by seventy Jewish Translators/Interpreters under royal compulsion during Ptolemy II's reign. That is con- firmed by historian Flavius Josephus (6), who writes that Ptolemy II, desirous to collect every book in the habitable Earth, applied Demetrius Phalereus (7) to the task of organizing an effort with the Jewish High Priests (8) to translate the Jewish books of the Law for his library. Josephus thus places the origins of the Septuagint in the 3rd century BC, when Demetrius and Ptolemy II lived. Accord- ing to Jewish legend, the seventy wrote their translations independently from memory, and the re- sultant works were identical at every letter. (b) + + + + + + + + + If you're seeking additional info about Christianity on a more personal level, consider visiting a Christian Church here in Marion County (9). Introduce yourself to members and ask to speak with someone to learn more about Jesus. Surrendering your life to Christ (10) (c) is the most rewarding, everlasting decision you'll ever make, and it's comforting to have someone guide you as you begin your new life as a child of the Most High! May God shower you with great favor in this endeavor! + + + + + + + + + Footnotes, Page Credits and External Resources appear on page 3.