Clustering of Integrin Β Cytoplasmic Domains Triggers Nascent Adhesion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigation of the Immune Receptors CEACAM3 and CEACAM4

Investigation of the human immune receptors CEACAM3 and CEACAM4 Dissertation Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) vorgelegt von Julia Delgado Tascón An der Universität Konstanz des Fachbereichs Biologie Konstanz, Oktober 2015 Konstanzer Online-Publikations-System (KOPS) URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-0-306516 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 05.11.2015 Vorsitzender und mündlicher Prüfer: Herr Professor Dr. Bürkle 1. Referent und und mündlicher Prüfer: Herr Professor Dr. Hauck 2. Referent und und mündlicher Prüfer: Herr Professor Dr. Tschan, Universität Bern A mi familia Acknowledgements I would like to express my special gratitude to my advisor Prof. Dr. Christof Hauck. His patient guidance and enthusiastic encouragement during these four years of PhD were a crucial aid to my process. I’m very thankful for his willingness and for granting me with his time in search for valuable and constructive suggestions during the planning and development of this research work. This certainly allowed me to grow as a person and as a scientist. I would also like to thank my committee members: to Prof. Dr. Mario Tschan for giving me his academic support at this last phase of my PhD thesis, and to Prof. M.Dr. Alexander Bürkle for his wise advices accompanied with Spanish greetings along this time. My thanks are extended to every member of the AG Hauck as well. To Anne, Susana, Petra and Claudia: thank you very much for your technical and personal guidance during these years. I’m also thankful to my fellow colleagues for countless ‘Kaffeepausen’ full of jokes, nice discussions, and delicious vegan cakes. -

Propranolol-Mediated Attenuation of MMP-9 Excretion in Infants with Hemangiomas

Supplementary Online Content Thaivalappil S, Bauman N, Saieg A, Movius E, Brown KJ, Preciado D. Propranolol-mediated attenuation of MMP-9 excretion in infants with hemangiomas. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4773 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/01/2021 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics Protein Name Prop 12 mo/4 Pred 12 mo/4 Δ Prop to Pred mo mo Myeloperoxidase OS=Homo sapiens GN=MPO 26.00 143.00 ‐117.00 Lactotransferrin OS=Homo sapiens GN=LTF 114.00 205.50 ‐91.50 Matrix metalloproteinase‐9 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MMP9 5.00 36.00 ‐31.00 Neutrophil elastase OS=Homo sapiens GN=ELANE 24.00 48.00 ‐24.00 Bleomycin hydrolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=BLMH 3.00 25.00 ‐22.00 CAP7_HUMAN Azurocidin OS=Homo sapiens GN=AZU1 PE=1 SV=3 4.00 26.00 ‐22.00 S10A8_HUMAN Protein S100‐A8 OS=Homo sapiens GN=S100A8 PE=1 14.67 30.50 ‐15.83 SV=1 IL1F9_HUMAN Interleukin‐1 family member 9 OS=Homo sapiens 1.00 15.00 ‐14.00 GN=IL1F9 PE=1 SV=1 MUC5B_HUMAN Mucin‐5B OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC5B PE=1 SV=3 2.00 14.00 ‐12.00 MUC4_HUMAN Mucin‐4 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC4 PE=1 SV=3 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 HRG_HUMAN Histidine‐rich glycoprotein OS=Homo sapiens GN=HRG 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 PE=1 SV=1 TKT_HUMAN Transketolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TKT PE=1 SV=3 17.00 28.00 ‐11.00 CATG_HUMAN Cathepsin G OS=Homo -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Demonstrates the Molecular and Cellular Reprogramming of Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16164-1 OPEN Single-cell RNA sequencing demonstrates the molecular and cellular reprogramming of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma Nayoung Kim 1,2,3,13, Hong Kwan Kim4,13, Kyungjong Lee 5,13, Yourae Hong 1,6, Jong Ho Cho4, Jung Won Choi7, Jung-Il Lee7, Yeon-Lim Suh8,BoMiKu9, Hye Hyeon Eum 1,2,3, Soyean Choi 1, Yoon-La Choi6,10,11, Je-Gun Joung1, Woong-Yang Park 1,2,6, Hyun Ae Jung12, Jong-Mu Sun12, Se-Hoon Lee12, ✉ ✉ Jin Seok Ahn12, Keunchil Park12, Myung-Ju Ahn 12 & Hae-Ock Lee 1,2,3,6 1234567890():,; Advanced metastatic cancer poses utmost clinical challenges and may present molecular and cellular features distinct from an early-stage cancer. Herein, we present single-cell tran- scriptome profiling of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma, the most prevalent histological lung cancer type diagnosed at stage IV in over 40% of all cases. From 208,506 cells populating the normal tissues or early to metastatic stage cancer in 44 patients, we identify a cancer cell subtype deviating from the normal differentiation trajectory and dominating the metastatic stage. In all stages, the stromal and immune cell dynamics reveal ontological and functional changes that create a pro-tumoral and immunosuppressive microenvironment. Normal resident myeloid cell populations are gradually replaced with monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells, along with T-cell exhaustion. This extensive single-cell analysis enhances our understanding of molecular and cellular dynamics in metastatic lung cancer and reveals potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets in cancer-microenvironment interactions. 1 Samsung Genome Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul 06351, Korea. -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Product Datasheet

Antibody Technology Product Data Sheet anti-human CEACAM8 monoclonal antibody Product information Catalog Number: GM-0512 Clone: GM2H6 Description: purified monoclonal mouse antibody Specificity: anti-human CEACAM8 (CD66b/NCA-95) Isotype: IgG1 Purification: Protein G Storage: short term: 2°C - 8°C; long term: -20°C (avoid repeated freezing and thawing) Buffer : phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.2 Immunogen: genetic immunisation with cDNA encoding human CEACAM8 Selection: based on recognition of the complete native protein expressed on transfected mammalian cells Working dilutions Flow cytometry: 1.2 µg/106 cells CELISA: 1:200 - 1:400 For each application a titration should be performed to determine the optimal concentration. Specificity testing by flow cytometry CEACAM8 transfectant control transfectant Fig.1: FACS analysis of BOSC23 cells using GM2H6 Cat.# GM- 0512. BOSC23 cells were transiently transfected with an expression vector encoding either CEACAM8 (red curve) or an irrelevant protein (control transfectant). Binding of GM-0512 was detected with a PE -conjugated secondary antibody. A positive signal was obtained only with CEACAM8 transfected cells. For research use only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. Aldevron Freiburg GmbH [email protected] Page 1 / 2 Waltershofener Str. 17 www.aldevron.com 79111 Freiburg, Germany Antibody Technology Antibody cross-reactivity with members of the CEA family CEACAM1 CEACAM3 CEACAM4 CEACAM5 CEACAM6 CEACAM7 CEACAM8 PSG1 Fig. 2: BOSC23 cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors containing either the cDNA of CEACAM1, CEACAM3-8 or PSG. The latter expressed as a membrane bound fusion protein. Expression of the constructs was tested with monoclonal antibodies known to recognize the corresponding proteins (CEACAM1,3,4,5 and 6: D14HD11; CEACAM7: BAC2; CEACAM8: Tet2; PSG: BAP3; green curves). -

Integrating Text Mining, Data Mining, and Network Analysis for Identifying

Jurca et al. BMC Res Notes (2016) 9:236 DOI 10.1186/s13104-016-2023-5 BMC Research Notes RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Integrating text mining, data mining, and network analysis for identifying genetic breast cancer trends Gabriela Jurca1, Omar Addam1, Alper Aksac1, Shang Gao2, Tansel Özyer3, Douglas Demetrick4 and Reda Alhajj1,5* Abstract Background: Breast cancer is a serious disease which affects many women and may lead to death. It has received considerable attention from the research community. Thus, biomedical researchers aim to find genetic biomarkers indicative of the disease. Novel biomarkers can be elucidated from the existing literature. However, the vast amount of scientific publications on breast cancer make this a daunting task. This paper presents a framework which investigates existing literature data for informative discoveries. It integrates text mining and social network analysis in order to identify new potential biomarkers for breast cancer. Results: We utilized PubMed for the testing. We investigated gene–gene interactions, as well as novel interactions such as gene-year, gene-country, and abstract-country to find out how the discoveries varied over time and how overlapping/diverse are the discoveries and the interest of various research groups in different countries. Conclusions: Interesting trends have been identified and discussed, e.g., different genes are highlighted in relation- ship to different countries though the various genes were found to share functionality. Some text analysis based results have been validated against results from other tools that predict gene–gene relations and gene functions. Keywords: Breast cancer, Data mining, Text mining, Network analysis Background reducing the number of molecules to consider as poten- Introduction tial biomarkers. -

CD Markers Are Routinely Used for the Immunophenotyping of Cells

ptglab.com 1 CD MARKER ANTIBODIES www.ptglab.com Introduction The cluster of differentiation (abbreviated as CD) is a protocol used for the identification and investigation of cell surface molecules. So-called CD markers are routinely used for the immunophenotyping of cells. Despite this use, they are not limited to roles in the immune system and perform a variety of roles in cell differentiation, adhesion, migration, blood clotting, gamete fertilization, amino acid transport and apoptosis, among many others. As such, Proteintech’s mini catalog featuring its antibodies targeting CD markers is applicable to a wide range of research disciplines. PRODUCT FOCUS PECAM1 Platelet endothelial cell adhesion of blood vessels – making up a large portion molecule-1 (PECAM1), also known as cluster of its intracellular junctions. PECAM-1 is also CD Number of differentiation 31 (CD31), is a member of present on the surface of hematopoietic the immunoglobulin gene superfamily of cell cells and immune cells including platelets, CD31 adhesion molecules. It is highly expressed monocytes, neutrophils, natural killer cells, on the surface of the endothelium – the thin megakaryocytes and some types of T-cell. Catalog Number layer of endothelial cells lining the interior 11256-1-AP Type Rabbit Polyclonal Applications ELISA, FC, IF, IHC, IP, WB 16 Publications Immunohistochemical of paraffin-embedded Figure 1: Immunofluorescence staining human hepatocirrhosis using PECAM1, CD31 of PECAM1 (11256-1-AP), Alexa 488 goat antibody (11265-1-AP) at a dilution of 1:50 anti-rabbit (green), and smooth muscle KD/KO Validated (40x objective). alpha-actin (red), courtesy of Nicola Smart. PECAM1: Customer Testimonial Nicola Smart, a cardiovascular researcher “As you can see [the immunostaining] is and a group leader at the University of extremely clean and specific [and] displays Oxford, has said of the PECAM1 antibody strong intercellular junction expression, (11265-1-AP) that it “worked beautifully as expected for a cell adhesion molecule.” on every occasion I’ve tried it.” Proteintech thanks Dr. -

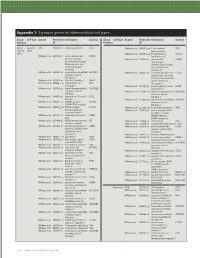

Technical Note, Appendix: an Analysis of Blood Processing Methods to Prepare Samples for Genechip® Expression Profiling (Pdf, 1

Appendix 1: Signature genes for different blood cell types. Blood Cell Type Source Probe Set Description Symbol Blood Cell Type Source Probe Set Description Symbol Fraction ID Fraction ID Mono- Lympho- GSK 203547_at CD4 antigen (p55) CD4 Whitney et al. 209813_x_at T cell receptor TRG nuclear cytes gamma locus cells Whitney et al. 209995_s_at T-cell leukemia/ TCL1A Whitney et al. 203104_at colony stimulating CSF1R lymphoma 1A factor 1 receptor, Whitney et al. 210164_at granzyme B GZMB formerly McDonough (granzyme 2, feline sarcoma viral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte- (v-fms) oncogene associated serine homolog esterase 1) Whitney et al. 203290_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQA1 Whitney et al. 210321_at similar to granzyme B CTLA1 complex, class II, (granzyme 2, cytotoxic DQ alpha 1 T-lymphocyte-associated Whitney et al. 203413_at NEL-like 2 (chicken) NELL2 serine esterase 1) Whitney et al. 203828_s_at natural killer cell NK4 (H. sapiens) transcript 4 Whitney et al. 212827_at immunoglobulin heavy IGHM Whitney et al. 203932_at major histocompatibility HLA-DMB constant mu complex, class II, Whitney et al. 212998_x_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQB1 DM beta complex, class II, Whitney et al. 204655_at chemokine (C-C motif) CCL5 DQ beta 1 ligand 5 Whitney et al. 212999_x_at major histocompatibility HLA-DQB Whitney et al. 204661_at CDW52 antigen CDW52 complex, class II, (CAMPATH-1 antigen) DQ beta 1 Whitney et al. 205049_s_at CD79A antigen CD79A Whitney et al. 213193_x_at T cell receptor beta locus TRB (immunoglobulin- Whitney et al. 213425_at Homo sapiens cDNA associated alpha) FLJ11441 fis, clone Whitney et al. 205291_at interleukin 2 receptor, IL2RB HEMBA1001323, beta mRNA sequence Whitney et al. -

Molecular Characteristics of Circulating Tumor Cells Resemble the Liver Metastasis More Closely Than the Primary Tumor in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Vol. 7, No. 37 Research Paper Molecular characteristics of circulating tumor cells resemble the liver metastasis more closely than the primary tumor in metastatic colorectal cancer Wendy Onstenk1, Anieta M. Sieuwerts1, Bianca Mostert1, Zarina Lalmahomed2, Joan B. Bolt-de Vries1, Anne van Galen1, Marcel Smid1, Jaco Kraan1, Mai Van1, Vanja de Weerd1, Raquel Ramírez-Moreno1, Katharina Biermann3, Cornelis Verhoef2, Dirk J. Grünhagen2, Jan N.M. IJzermans2, Jan W. Gratama1, John W.M. Martens1, John A. Foekens1, Stefan Sleijfer1 1Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Department of Medical Oncology and Cancer Genomics Netherlands, Rotterdam, The Netherlands 2Department of Surgery, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands 3Department of Pathology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Correspondence to: Wendy Onstenk, email: [email protected] Keywords: circulating tumor cells, CTCs, CellSearch, colorectal cancer, gene expression profiling Received: April 06, 2016 Accepted: May 29, 2016 Published: June 20, 2016 ABSTRACT Background: CTCs are a promising alternative for metastatic tissue biopsies for use in precision medicine approaches. We investigated to what extent the molecular characteristics of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) resemble the liver metastasis and/ or the primary tumor from patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). Results: The CTC profiles were concordant with the liver metastasis in 17/23 patients (74%) and with the primary tumor in 13 patients (57%). The CTCs better resembled the liver metastasis in 13 patients (57%), and the primary tumor in five patients (22%). The strength of the correlations was not associated with clinical parameters. Nine genes (CDH1, CDH17, CDX1, CEACAM5, FABP1, FCGBP, IGFBP3, IGFBP4, and MAPT) displayed significant differential expressions, all of which were downregulated, in CTCs compared to the tissues in the 23 patients. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Systemic Surfaceome Profiling Identifies Target Antigens for Immune-Based Therapy in Subtypes of Advanced Prostate Cancer

Systemic surfaceome profiling identifies target antigens for immune-based therapy in subtypes of advanced prostate cancer John K. Leea,b,c, Nathanael J. Bangayand, Timothy Chaie, Bryan A. Smithf, Tiffany E. Parivaf, Sangwon Yung, Ajay Vashishth, Qingfu Zhangi,j, Jung Wook Parkf, Eva Coreyk, Jiaoti Huangi, Thomas G. Graeberc,d,l,m, James Wohlschlegelh, and Owen N. Wittec,d,f,n,o,1 aDivision of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; bInstitute of Urologic Oncology, Department of Urology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; cJonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; dDepartment of Molecular and Medical Pharmacology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; eStanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA 94305; fDepartment of Microbiology, Immunology, and Medical Genetics, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; gYale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06510; hDepartment of Biological Chemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; iDepartment of Pathology, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC 27708; jDepartment of Pathology, China Medical University, 110001 Shenyang, People’s Republic of China; kDepartment of Urology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA 98195; lCrump Institute for Molecular Imaging, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; mUCLA Metabolomics Center, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 900095; nParker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy,