STATE of FLORIDA DEPARTMENT of NATURAL RESOURCES Elton J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FWC Division of Law Enforcement South Region

FWC Division of Law Enforcement South Region – Bravo South Region B Comprised of: • Major Alfredo Escanio • Captain Patrick Langley (Key West to Marathon) – Lieutenants Roy Payne, George Cabanas, Ryan Smith, Josh Peters (Sanctuary), Kim Dipre • Captain David Dipre (Marathon to Dade County) – Lieutenants Elizabeth Riesz, David McDaniel, David Robison, Al Maza • Pilot – Officer Daniel Willman • Investigators – Carlo Morato, John Brown, Jeremy Munkelt, Bryan Fugate, Racquel Daniels • 33 Officers • Erik Steinmetz • Seth Wingard • Wade Hefner • Oliver Adams • William Burns • John Conlin • Janette Costoya • Andy Cox • Bret Swenson • Robb Mitchell • Rewa DeBrule • James Johnson • Robert Dube • Kyle Mason • Michael Mattson • Michael Bulger • Danielle Bogue • Steve Golden • Christopher Mattson • Steve Dion • Michael McKay • Jose Lopez • Scott Larosa • Jason Richards • Ed Maldonado • Adam Garrison • Jason Rafter • Marty Messier • Sebastian Dri • Raul Pena-Lopez • Douglas Krieger • Glen Way • Clayton Wagner NOAA Offshore Vessel Peter Gladding 2 NOAA near shore Patrol Vessels FWC Sanctuary Officers State Law Enforcement Authority: F. S. 379.1025 – Powers of the Commission F. S. 379.336 – Citizens with violations outside of state boundaries F. S. 372.3311 – Police Power of the Commission F. S. 910.006 – State Special Maritime Jurisdiction Federal Law Enforcement Authority: U.S. Department of Commerce - National Marine Fisheries Service U.S. Department of the Interior - U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service U.S. Department of the Treasury - U.S. Customs Service -

Coast Guard, DHS § 7.100

Coast Guard, DHS § 7.100 the easternmost extremity of Black- (e) A line drawn across the seaward beard Island at Northeast Point. extremity of the Sebastian Inlet Jet- (d) A line drawn from the southern- ties. most extremity of Blackbeard Island to (f) A line drawn from the seaward ex- latitude 31°19.4′ N. longitude 81°11.5′ W. tremity of the Fort Pierce Inlet North (Doboy Sound Lighted Buoy ‘‘D’’); Jetty to latitude 27°28.5′ N. longitude thence to latitude 31°04.1′ N. longitude 80°16.2′ W. (Fort Pierce Inlet Lighted 81°16.7′ W. (St. Simons Lighted Whistle Whistle Buoy ‘‘2’’); thence to the tank Buoy ‘‘ST S’’). located in approximate position lati- tude 27°27.2′ N. longitude 80°17.2′ W. § 7.85 St. Simons Island, GA to Little (g) A line drawn from the seaward ex- Talbot Island, FL. tremity of St. Lucie Inlet north jetty (a) A line drawn from latitude 31°04.1′ to latitude 27°10′ N. longitude 80°08.4′ N. longitude 81°16.7′ W. (St. Simons W. (St. Lucie Inlet Entrance Lighted Lighted Whistle Buoy ‘‘ST S’’) to lati- Whistle Buoy ‘‘2’’); thence to Jupiter tude 30°42.7′ N. longitude 81°19.0′ W. (St. Island bearing approximately 180° true. Mary’s Entrance Lighted Whistle Buoy (h) A line drawn from the seaward ex- ‘‘1’’); thence to Amelia Island Light. tremity of Jupiter Inlet North Jetty to (b) A line drawn from the southern- the northeast extremity of the con- most extremity of Amelia Island to crete apron on the south side of Jupiter latitude 30°29.4′ N. -

ISAIAS (AL092020) 30 July–4 August 2020

NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT HURRICANE ISAIAS (AL092020) 30 July–4 August 2020 Andy Latto, Andrew Hagen, and Robbie Berg National Hurricane Center 1 11 June 2021 GOES-16 10.3-µM INFRARED SATELLITE IMAGE OF HURRICANE ISAIAS AT 0310 UTC 04 AUGUST 2020 AS IT MADE LANDFALL NEAR OCEAN ISLE BEACH, NORTH CAROLINA. Isaias was a hurricane that formed in the eastern Caribbean Sea. The storm affected the Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Cuba, the Bahamas, and a large portion of the eastern United States. 1 Original report date 30 March 2021. Second version on 15 April updated Figure 12. This version corrects a wind gust value in the Winds and Pressures section and the track length of a tornado in Delaware. Hurricane Isaias 2 Table of Contents SYNOPTIC HISTORY .......................................................................................... 3 METEOROLOGICAL STATISTICS ...................................................................... 5 Winds and Pressure ........................................................................................... 5 Caribbean Islands and Bahamas ..................................................................... 6 United States ................................................................................................... 6 Rainfall and Flooding ......................................................................................... 7 Storm Surge ....................................................................................................... 8 Tornadoes ....................................................................................................... -

MSRP Appendix A

APPENDIX A: RECOVERY TEAM MEMBERS Multi-Species Recovery Plan for South Florida Appendix A. Names appearing in bold print denote those who authored or prepared Appointed Recovery various components of the recovery plan. Team Members Ralph Adams Geoffrey Babb Florida Atlantic University The Nature Conservancy Biological Sciences 222 South Westmonte Drive, Suite 300 Boca Raton, Florida 33431 Altimonte Springs, Florida 32714-4236 Ross Alliston Alice Bard Monroe County, Environmental Florida Department of Environmental Resource Director Protection 2798 Overseas Hwy Florida Park Service, District 3 Marathon , Florida 33050 1549 State Park Drive Clermont, Florida 34711 Ken Alvarez Florida Department of Enviromental Bob Barron Protection U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Florida Park Service, 1843 South Trail Regulatory Division Osprey, Florida 34229 P.O. Box 4970 Jacksonville, Florida 32232-0019 Loran Anderson Florida State University Oron L. “Sonny” Bass Department of Biological Science National Park Service Tallahassee, Florida 32306-2043 Everglades National Park 40001 State Road 9336 Tom Armentano Homestead, Florida 33034-6733 National Park Service Everglades National Park Steven Beissinger 40001 State Road 9336 Yale University - School of Homestead, Florida 33034-6733 Forestry & Environmental Studies Sage Hall, 205 Prospect Street David Arnold New Haven, Connecticut 06511 Florida Department of Environmental Protection Rob Bennetts 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard P.O. Box 502 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-3000 West Glacier, Montana 59936 Daniel F. Austin Michael Bentzien Florida Atlantic University U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Sciences Jacksonville Field Office 777 Glades Road 6620 Southpoint Drive South, Suite 310 Boca Raton, Florida 33431 Jacksonville, Florida 32216-0912 David Auth Nancy Bissett University of Florida The Natives Florida Museum of Natural History 2929 J.B. -

Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets

Keys TravelerThe Magazine Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets fla-keys.com Decompresssing at Bahia Honda State Park near Big Pine Key in the Lower Florida Keys. ANDY NEWMAN MARIA NEWMAN Keys Traveler 12 The Magazine Editor Andy Newman Managing Editor 8 4 Carol Shaughnessy ROB O’NEAL ROB Copy Editor Buck Banks Writers Julie Botteri We do! Briana Ciraulo Chloe Lykes TIM GROLLIMUND “Keys Traveler” is published by the Monroe County Tourist Development Contents Council, the official visitor marketing agency for the Florida Keys & Key West. 4 Sanctuary Protects Keys Marine Resources Director 8 Outdoor Art Enriches the Florida Keys Harold Wheeler 9 Epic Keys: Kiteboarding and Wakeboarding Director of Sales Stacey Mitchell 10 That Florida Keys Sunset! Florida Keys & Key West 12 Keys National Parks Join Centennial Celebration Visitor Information www.fla-keys.com 14 Florida Bay is a Must-Do Angling Experience www.fla-keys.co.uk 16 Race Over Water During Key Largo Bridge Run www.fla-keys.de www.fla-keys.it 17 What’s in a Name? In Marathon, Plenty! www.fla-keys.ie 18 Visit Indian and Lignumvitae Keys Splash or Relax at Keys Beaches www.fla-keys.fr New Arts District Enlivens Key West ach of the Florida Keys’ regions, from Key Largo Bahia Honda State Park, located in the Lower Keys www.fla-keys.nl www.fla-keys.be Stroll Back in Time at Crane Point to Key West, features sandy beaches for relaxing, between MMs 36 and 37. The beaches of Bahia Honda Toll-Free in the U.S. -

Final 2012 NHLPA Report Noapxb.Pub

GSA Office of Real Property Utilization and Disposal 2012 PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS REPORT NATIONAL HISTORIC LIGHTHOUSE PRESERVATION ACT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lighthouses have played an important role in America’s For More Information history, serving as navigational aids as well as symbols of our rich cultural past. Congress passed the National Information about specific light stations in the Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act (NHLPA) in 2000 to NHLPA program is available in the appendices and establish a lighthouse preservation program that at the following websites: recognizes the cultural, recreational, and educational National Park Service Lighthouse Heritage: value of these iconic properties, especially for local http://www.nps.gov/history/maritime/lt_index.htm coastal communities and nonprofit organizations as stewards of maritime history. National Park Service Inventory of Historic Light Stations: http://www.nps.gov/maritime/ltsum.htm Under the NHLPA, historic lighthouses and light stations (lights) are made available for transfer at no cost to Federal agencies, state and local governments, and non-profit organizations (i.e., stewardship transfers). The NHLPA Progress To Date: NHLPA program brings a significant and meaningful opportunity to local communities to preserve their Since the NHLPA program’s inception in 2000, 92 lights maritime heritage. The program also provides have been transferred to eligible entities. Sixty-five substantial cost savings to the United States Coast percent of the transferred lights (60 lights) have been Guard (USCG) since the historic structures, expensive to conveyed through stewardship transfers to interested repair and maintain, are no longer needed by the USCG government or not-for-profit organizations, while 35 to meet its mission as aids to navigation. -

Fkeys-CMP.Pdf

Florida KEYS Scenic Highway corridor management plan Submitted to Florida Department of Transportation, District Six Scenic Highways Coordinator 602 South Miami Avenue Miami, FL 33130 Submitted by The Florida Keys Scenic Highway CAG June Helbling and Kathy Toribio, Co-Chairs c/o Clean Florida Keys, Inc. PO Box 1528 Key West, FL 33041-1528 Prepared by The Florida Keys Scenic Highway CAG Peggy Fowler, Planning Consultant Patricia Fontova, Graphic Designer Carter and Burgess, Inc., Planning Consultants May, 2001 This document was prepared in part with funding from the Florida Department of Transportation. This document is formatted for 2-sided printing. Some pages were left intentionally blank for that reason. Table of Contents Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION .....................................................1 Chapter 2: CORRIDOR VISION ..................................................5 Chapter 3: CORRIDOR STORY ..................................................7 Chapter 4: DESIGNATION CRITERIA .......................................13 Chapter 5: BACKGROUND CONDITONS ANALYSIS ...............27 Chapter 6: RELATIONSHIP TO COMPREHENSIVE PLAN .......59 Chapter 7: PROTECTION TECHNIQUES................................ .63 Chapter 8: COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION ..............................69 Chapter 9: PARTNERSHIPS AND AGREEMENTS.................... .79 Chapter 10: FUNDING AND PROMOTION ...............................85 Chapter 11: GOALS, OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES ................93 Chapter 12: ACTION PLAN .........................................................97 -

HURRICANE IRMA (AL112017) 30 August–12 September 2017

NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT HURRICANE IRMA (AL112017) 30 August–12 September 2017 John P. Cangialosi, Andrew S. Latto, and Robbie Berg National Hurricane Center 1 24 September 2021 VIIRS SATELLITE IMAGE OF HURRICANE IRMA WHEN IT WAS AT ITS PEAK INTENSITY AND MADE LANDFALL ON BARBUDA AT 0535 UTC 6 SEPTEMBER. Irma was a long-lived Cape Verde hurricane that reached category 5 intensity on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. The catastrophic hurricane made seven landfalls, four of which occurred as a category 5 hurricane across the northern Caribbean Islands. Irma made landfall as a category 4 hurricane in the Florida Keys and struck southwestern Florida at category 3 intensity. Irma caused widespread devastation across the affected areas and was one of the strongest and costliest hurricanes on record in the Atlantic basin. 1 Original report date 9 March 2018. Second version on 30 May 2018 updated casualty statistics for Florida, meteorological statistics for the Florida Keys, and corrected a typo. Third version on 30 June 2018 corrected the year of the last category 5 hurricane landfall in Cuba and corrected a typo in the Casualty and Damage Statistics section. This version corrects the maximum wind gust reported at St. Croix Airport (TISX). Hurricane Irma 2 Hurricane Irma 30 AUGUST–12 SEPTEMBER 2017 SYNOPTIC HISTORY Irma originated from a tropical wave that departed the west coast of Africa on 27 August. The wave was then producing a widespread area of deep convection, which became more concentrated near the northern portion of the wave axis on 28 and 29 August. -

Tropical Garden Summer 2016

SUMMER 2016 Summer’s bounty in the tropics published by fairchild tropical botanic garden The Shop AT FAIRCHILD GARDENING SUPPLIES | UNIQUE TROPICAL GIFTS | APPAREL HOME DÉCOR | BOOKS | ECO-FRIENDLY AND FAIR-TraDE PRODUCTS ACCESSORIES | TROPICAL GOURMET FOODS | ORCHIDS AND MUCH MORE @ShopatFairchild SHOP HOURS: 9:00 A.M. - 5:30 P.M. SHOP ONLINE AT STORE.FAIRCHILDONLINE.COM contents FEATURES THE WORK OF CONSERVATION 18 37 THE FIGS OF FAIRCHILD DEPARTMENTS 4 FROM THE DIRECTOR 5 FROM THE CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER 7 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 9 GET IN ON THE CONSERVATION 11 EXPLAINING 14 VIS-A-VIS VOLUNTEERS 17 THE ART IN GARTEN 18 CONSERVING 21 what’s in a name 28 what’s blooming 30 EXPLORING 37 PLANT COLLECTIONS 41 what’s in store 43 PLANT SOCIETIES EXPLORING THE WINDSWEPT 49 EDIBLE GARDENING ISLAND OF GREAT INAGUA 30 50 SOUTH FLORIDA GARDENING 53 BUG BEAT 59 BOOK REVIEW 60 FROM THE ARCHIVES 63 VISTAS 64 GARDEN VIEWS SUMMER 2016 3 from the director ummer at Fairchild is a time when we think about the future, a time for setting plans into motion for the years ahead. It’s when we add new plants to our landscape, launch research projects and develop training programs for our new recruits in botany. Summertime is when our best ideas begin to take shape. SSummertime is also when we keep an extra-vigilant eye on the warm Atlantic tropical waters. During hurricane season, we are constantly aware that everything we do, all of our dreams and hard work, are at risk of being knocked out whenever a storm spins toward South Florida. -

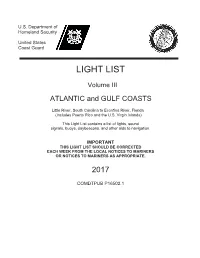

USCG Light List

U.S. Department of Homeland Security United States Coast Guard LIGHT LIST Volume III ATLANTIC and GULF COASTS Little River, South Carolina to Econfina River, Florida (Includes Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) This /LJKW/LVWFRQWDLQVDOLVWRIOLJKWV, sound signals, buoys, daybeacons, and other aids to navigation. IMPORTANT THIS /,*+7/,67 SHOULD BE CORRECTED EACH WEEK FROM THE LOCAL NOTICES TO MARINERS OR NOTICES TO MARINERS AS APPROPRIATE. 2017 COMDTPUB P16502.1 C TES O A A T S T S G D U E A T U.S. AIDS TO NAVIGATION SYSTEM I R N D U 1790 on navigable waters except Western Rivers LATERAL SYSTEM AS SEEN ENTERING FROM SEAWARD PORT SIDE PREFERRED CHANNEL PREFERRED CHANNEL STARBOARD SIDE ODD NUMBERED AIDS NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED EVEN NUMBERED AIDS PREFERRED RED LIGHT ONLY GREEN LIGHT ONLY PREFERRED CHANNEL TO CHANNEL TO FLASHING (2) FLASHING (2) STARBOARD PORT FLASHING FLASHING TOPMOST BAND TOPMOST BAND OCCULTING OCCULTING GREEN RED QUICK FLASHING QUICK FLASHING ISO ISO GREEN LIGHT ONLY RED LIGHT ONLY COMPOSITE GROUP FLASHING (2+1) COMPOSITE GROUP FLASHING (2+1) 9 "2" R "8" "1" G "9" FI R 6s FI R 4s FI G 6s FI G 4s GR "A" RG "B" LIGHT FI (2+1) G 6s FI (2+1) R 6s LIGHTED BUOY LIGHT LIGHTED BUOY 9 G G "5" C "9" GR "U" GR RG R R RG C "S" N "C" N "6" "2" CAN DAYBEACON "G" CAN NUN NUN DAYBEACON AIDS TO NAVIGATION HAVING NO LATERAL SIGNIFICANCE ISOLATED DANGER SAFE WATER NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED WHITE LIGHT ONLY WHITE LIGHT ONLY MORSE CODE FI (2) 5s Mo (A) RW "N" RW RW RW "N" Mo (A) "A" SP "B" LIGHTED MR SPHERICAL UNLIGHTED C AND/OR SOUND AND/OR SOUND BR "A" BR "C" RANGE DAYBOARDS MAY BE LETTERED FI (2) 5s KGW KWG KWB KBW KWR KRW KRB KBR KGB KBG KGR KRG LIGHTED UNLIGHTED DAYBOARDS - MAY BE LETTERED WHITE LIGHT ONLY SPECIAL MARKS - MAY BE LETTERED NR NG NB YELLOW LIGHT ONLY FIXED FLASHING Y Y Y "A" SHAPE OPTIONAL--BUT SELECTED TO BE APPROPRIATE FOR THE POSITION OF THE MARK IN RELATION TO THE Y "B" RW GW BW C "A" N "C" Bn NAVIGABLE WATERWAY AND THE DIRECTION FI Bn Bn Bn OF BUOYAGE. -

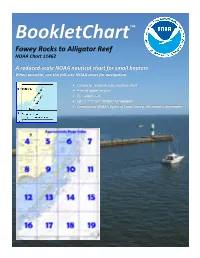

Bookletchart™ Fowey Rocks to Alligator Reef NOAA Chart 11462

BookletChart™ Fowey Rocks to Alligator Reef NOAA Chart 11462 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the daybeacons, leads from the ocean 0.6 mile southward of Pacific Reef Light to Caesar Creek; the reported controlling depth was 8 feet. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration A sunken wreck was reported in Hawk Channel 0.3 mile northwest of National Ocean Service Turtle Harbor West Shoal Daybeacon 2. Office of Coast Survey Ocean Reef Harbor is on the east side of Key Largo. A privately dredged channel leads to the harbor. The depth in the channel was 7 feet. The www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov entrance channel is marked by a light and private daybeacons. The 888-990-NOAA harbor has good anchorage. A private yacht club is on the north side of the harbor. What are Nautical Charts? An obstruction was reported 0.6 mile east-southeastward of the entrance channel in about 25°18'19.4"N., 80°15'35.2"W. Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show Key Largo Anchorage, 20 miles southwestward of Fowey Rocks Light, is water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much fair in all but southerly winds. It has a depth of 14 feet, soft bottom, 4.5 more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and miles northwestward of Carysfort Reef Light. efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial Turtle Harbor, a well-sheltered anchorage between the reefs lying ships that carry America’s commerce. -

Mile Marker 0-65 (Lower Keys)

Key to Map: Map is not to scale Existing Florida Keys Overseas Heritage Trail Aquatic Preserves or Alternate Path Overseas Paddling Trail U.S. 1 Point of Interest U.S. Highway 1 TO MIAMI Kayak/Canoe Launch Site CARD SOUND RD Additional Paths and Lanes TO N KEY LARGO Chamber of Commerce (Future) Trailhead or Rest Area Information Center Key Largo Dagny Johnson Trailhead Mangroves Key Largo Hammock Historic Bridge-Fishing Botanical State Park Islands Historic Bridge Garden Cove MM Mile Marker Rattlesnake Key MM 105 Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Office of Greenways & Trails Florida Keys Overseas Heritage Trail Office: (305) 853-3571 Key Largo Adams Waterway FloridaGreenwaysAndTrails.com El Radabob Key John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park MM 100 Swash Friendship Park Keys Key Largo Community Park Florida Keys Community of Key Largo FLORIDA BAY MM 95 Rodriguez Key Sunset Park Dove Key Overseas Heritage Trail Town of Tavernier Harry Harris Park Burton Drive/Bicycle Lane MM 90 Tavernier Key Plantation Key Tavernier Creek Lignumvitae Key Aquatic Preserve Founders Park ATLANTIC OCEAN Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park MM 85 Snake Creek Long Key Historic Bridge TO UPPER Islamorada, Village of Islands Whale Harbor Channel GULF OF MEXICO KEYS Tom's Harbor Cut Historic Bridge Wayside Rest Area Upper Matecumbe Key Tom's Harbor Channel Historic Bridge MM 80 Dolphin Research Center Lignumvitae Key Botanical State Park Tea Table Key Relief Channel Grassy Key MM 60 Conch Keys Tea Table Channel Grassy Key Rest Area Indian Key