Some Facts About Scotland and Scots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Orkney Native Wildlife Project

The Orkney Native Wildlife Project Strategic Environmental Assessment Environmental Report June 2020 1 / 31 Orkney Native Wildlife Project Environmental Report 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Project Summary and Objectives ............................................................................. 4 1.2 Policy Context............................................................................................................ 4 1.3 Related Plans, Programmes and Strategies ............................................................ 4 2. SEA METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Topics within the scope of assessment .............................................................. 6 2.2 Assessment Approach .............................................................................................. 6 2.3 SEA Objectives .......................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Limitations to the Assessment ................................................................................. 8 3. ENVIRONMENTAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PROJECT AREA ............................. 8 3.1 Biodiversity, Flora and Fauna ................................................................................... 8 3.2 Population and Human Health .................................................................................. 9 -

Cruising the ISLANDS of ORKNEY

Cruising THE ISLANDS OF ORKNEY his brief guide has been produced to help the cruising visitor create an enjoyable visit to TTour islands, it is by no means exhaustive and only mentions the main and generally obvious anchorages that can be found on charts. Some of the welcoming pubs, hotels and other attractions close to the harbour or mooring are suggested for your entertainment, however much more awaits to be explored afloat and many other delights can be discovered ashore. Each individual island that makes up the archipelago offers a different experience ashore and you should consult “Visit Orkney” and other local guides for information. Orkney waters, if treated with respect, should offer no worries for the experienced sailor and will present no greater problem than cruising elsewhere in the UK. Tides, although strong in some parts, are predictable and can be used to great advantage; passage making is a delight with the current in your favour but can present a challenge when against. The old cruising guides for Orkney waters preached doom for the seafarer who entered where “Dragons and Sea Serpents lie”. This hails from the days of little or no engine power aboard the average sailing vessel and the frequent lack of wind amongst tidal islands; admittedly a worrying combination when you’ve nothing but a scrap of canvas for power and a small anchor for brakes! Consult the charts, tidal guides and sailing directions and don’t be afraid to ask! You will find red “Visitor Mooring” buoys in various locations, these are removed annually over the winter and are well maintained and can cope with boats up to 20 tons (or more in settled weather). -

Scottish Birds

SCOTTISH BIRDS THE JOURNAL OF THE SCOTTISH ORNITHOLOGISTS' CLUB Volume 7 No. 7 AUTUMN 1973 Price SOp SCOTTISH BIRD REPORT 1972 1974 SPECIAL INTEREST TOURS by PEREGRINE HOLIDAYS Directors : Ray Hodgkins, MA. (Oxon) MTAI and Patricia Hodgkins, MTAI. Each tour has been surveyed by one or both of the directors and / or chief guest lecturer; each tour is accompanied by an experienced tour manager (usually one of the directors) in addition to the guest lecturers. All Tours by Scheduled Air Services of International Air Transport Association Airlines such as British Airways, Olympic Airways and Air India. INDIA & NEPAL-Birds and Large Mammals-Sat. 16 February. 20 days. £460.00. A comprehensive tour of the Game Parks (and Monuments) planned after visits by John Gooders and Patricia and Ray Hodgkins. Includes a three-night stay at the outstandingly attractive Tiger Tops Jungle Lodge and National Park where there is as good a chance as any of seeing tigers in the really natural state. Birds & Animals--John Gooders B.Sc., Photography -Su Gooders, Administration-Patricia Hodgkins, MTAI. MAINLAND GREECE & PELOPONNESE-Sites & Flowers-15 days. £175.00. Now known as Dr Pinsent's tour this exhilarating interpretation of Ancient History by our own enthusiastic eponymous D. Phil is in its third successful year. Accompanied in 1974 by the charming young lady botanist who was on the 1973 tour it should both in experience and content be a vintage tour. Wed. 3 April. Sites & Museums-Dr John Pinsent, Flowers-Miss Gaye Dawson. CRETE-Bird and Flower Tours-15 days. £175.00. The Bird and Flower Tours of Crete have steadily increased in popularity since their inception in 1970 with the late Or David Lack, F.R.S. -

4Rt*Cqn! Leadership Award I Am Trying to Find the Birthplace in Lreland, Donnienicholson Led Ateamto Rowfrom St

Glasgow 2015 Donnie Nicholson 9Lente ftpl,p Games photos here for vou! wins Scottish n'tl 4rt*cqn! leadership award I am trying to find the birthplace in lreland, DonnieNicholson led ateamto rowfrom St. Kilda of my 6th great-great to the Isle of Skye. For that accomplishment, he was grandfathern Hugh chosen to win a Leadership Award from the British Na- Harkins. tional Adventure Awards committee for National Ad- venture for organizing his team, who came close to also He came to being awarded the Team Award. Charleston, S.C. in The team, from a small community onthe Isle of May 1767 on the gottogetherto Skye rejuvenate an old boatbuilt in 1890, Prince of Wales the Aurora, androw it for one hundred miles between withhiswife the remote St. Kilda and Skye. Elizabeth. Donnie gathered the team, tained them and moti- vated them; it said much for Donnie's leadership skills. I do not knowwhere/ The entire proj ect was all to raise funds for the Royal howto determine Naval Lifeboat hstitition and Skye Young Carers. some Donnie and Rosie McDade, the Coxswain ofthe document that might boat, recently became the proud parents of a daughter, indicate the parish/ There are two HollyRoseNicolson. town/countyinwhich pages of photos With thank s to Sc onvbre ac. The Journal of Clan they lived. MacNicol of North Am.ti"ffa'* from the 20I5 Any help or advice is Glasgow High- appreciated. land Games on regards, pages I2-13 of Charles Harkins this section, in- charkins8589@aolcom cluding this hand- some young man. re ffi MEf,TBERSHIP VICE PRESIDENT TtAE'VTBERSI{IP Clifford Fitzsimmons Alon Grohom '19 29.|9 Denson Avenue Broe Volley Courl Knoxville, TN 37921-6671 Porf Perry, Onlorio LgL 1V1, Conodo cehl [email protected] clon.grohom.conodo. -

Black's Morayshire Directory, Including the Upper District of Banffshire

tfaU. 2*2. i m HE MOR CTORY. * i e^ % / X BLACKS MORAYSHIRE DIRECTORY, INCLUDING THE UPPER DISTRICTOF BANFFSHIRE. 1863^ ELGIN : PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY JAMES BLACK, ELGIN COURANT OFFICE. SOLD BY THE AGENTS FOR THE COURANT; AND BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. : ELGIN PRINTED AT THE COURANT OFFICE, PREFACE, Thu ''Morayshire Directory" is issued in the hope that it will be found satisfactorily comprehensive and reliably accurate, The greatest possible care has been taken in verifying every particular contained in it ; but, where names and details are so numerous, absolute accuracy is almost impossible. A few changes have taken place since the first sheets were printed, but, so far as is known, they are unimportant, It is believed the Directory now issued may be fully depended upon as a Book of Reference, and a Guide for the County of Moray and the Upper District of Banffshire, Giving names and information for each town arid parish so fully, which has never before been attempted in a Directory for any County in the JTorth of Scotland, has enlarged the present work to a size far beyond anticipation, and has involved much expense, labour, and loss of time. It is hoped, however, that the completeness and accuracy of the Book, on which its value depends, will explain and atone for a little delay in its appearance. It has become so large that it could not be sold at the figure first mentioned without loss of money to a large extent, The price has therefore been fixed at Two and Sixpence, in order, if possible, to cover outlays, Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/blacksmorayshire1863dire INDEX. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRApHY PRIMARY SOURCEs Conversations and Correspondence with Lady Mary Whitley, Countess Mountbatten, Maitre Blum and Dr. Heald Judgements and Case Reports Newell, Ann: The Secret Life of Ellen, Lady Kilmorey, unpublished dissertation, 2016 Royal Archives, Windsor The Kilmorey Papers: Public Record Office of Northern Ireland The Teck Papers: Wellington College SECONDARY SOURCEs Aberdeen, Isobel. 1909. Marchioness of, Notes & Recollections. London: Constable. Annual Register Astle, Thomas. 1775. The Will of Henry VII. ECCO Print editions. Bagehot, Walter. 1867 (1872). The English Constitution. Thomas Nelson & Sons. Baldwin-Smith, Lacey. 1971. Henry VIII: The Mask of Royalty. London: Jonathan Cape. Benn, Anthony Wedgwood. 1993. Common Sense: A New Constitution for Britain, (with Andrew Hood). Brooke, the Hon. Sylvia Brooke. 1970. Queen of the Headhunters. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. Chamberlin, Frederick. 1925. The Wit & Wisdom of Good Queen Bess. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head. © The Author(s) 2017 189 M.L. Nash, Royal Wills in Britain from 1509 to 2008, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-60145-2 190 BIBLIOGRAPHY Chevenix-Trench, Charles. 1964. The Royal Malady. New York: Harcourt, Bruce & World Cronin, Vincent. 1964 (1990). Louis XIV. London: Collins Harvel. Davey, Richard. 1909. The Nine Days’ Queen. London: Methuen & Co. ———. 1912. The Sisters of Lady Jane Grey. New York: E.R. Dutton. De Lisle, Leanda. 2004. After Elizabeth: The Death of Elizabeth, and the Coming of King James. London: Harper Collins. Doran, John. 1875. Lives of the Queens of England of the House of Hanover, vols I & II. London: Richard Bentley & Sons. Edwards, Averyl. 1947. Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales. London/New York/ Toronto: Staples Press. -

Across the Pond...A Word from Our Chief, Sir Malcolm Macgregor

Ardchoille Newsletter of the American Clan Gregor Society Volume XVIII, Issue 1I Summer 2012 Across The Pond...a word from our Chief, Sir Malcolm MacGregor The big event in Inside this issue: Scotland over these past months has been From The Desk Of The Chieftain 2 the official celebrations Scottish Life In Texas of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Clan Gregor Tartan 3 throughout the United Kingdom. The Union 4 flag has been on Clan Gregor Tartan; Con’t... display everywhere. In Dundee, Captain 5 Call To Action! Scott’s ship the Discovery had a huge Clan Gregor Tartan; Con’t… 6 Did You Know? Union Jack on the bow mast with bunting across the decks. There were two huge street parties in Edinburgh, which Honoring A War Hero 7 certainly competed with those in London. Crossing Over Clan Gregor In Tampa! The Queen herself is regarded as ‘chief of chiefs’ and is head of the Royal House of Stewart. The Stewarts have numerous ‘houses’ rather than being a unified clan. Her connection to th For The Kids Word Search! 8 Scotland descends primarily from the Stewart kings who reigned in Scotland in the 16 century and went onto reign under a union of crowns in the 17th century. Newsletter Editor Fiona and I attended the lighting of one of the myriad of Carol Spitznagle 2,000 bonfires lit across the land from the cliffs of Dover to 6470 Harding Street Shetland. We were on Kinpurnie Hill in Angus, the site of an Hollywood, Fl. 33024 ancient bronze age fort. -

Sir Walter Scott's Templar Construct

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. SIR WALTER SCOTT’S TEMPLAR CONSTRUCT – A STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY INFLUENCES ON HISTORICAL PERCEPTIONS. A THESIS PRESENTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY AT MASSEY UNIVERSITY, EXTRAMURAL, NEW ZEALAND. JANE HELEN WOODGER 2017 1 ABSTRACT Sir Walter Scott was a writer of historical fiction, but how accurate are his portrayals? The novels Ivanhoe and Talisman both feature Templars as the antagonists. Scott’s works display he had a fundamental knowledge of the Order and their fall. However, the novels are fiction, and the accuracy of some of the author’s depictions are questionable. As a result, the novels are more representative of events and thinking of the early nineteenth century than any other period. The main theme in both novels is the importance of unity and illustrating the destructive nature of any division. The protagonists unify under the banner of King Richard and the Templars pursue a course of independence. Scott’s works also helped to formulate notions of Scottish identity, Freemasonry (and their alleged forbearers the Templars) and Victorian behaviours. However, Scott’s image is only one of a long history of Templars featuring in literature over the centuries. Like Scott, the previous renditions of the Templars are more illustrations of the contemporary than historical accounts. One matter for unease in the early 1800s was religion and Catholic Emancipation. -

PUBLIC PETITION NO. PE01541 Name Of

PUBLIC PETITION NO. PE01541 Name of petitioner Chris Cromar Petition title 'Flower of Scotland' to be officially recognised as Scotland's national anthem Petition summary Calling on the Scottish Parliament to urge the Scottish Government to Offically recognise 'Flower of Scotland' as Scotland's national anthem. Action taken to resolve issues of concern before submitting the petition In my time as a Member of the Scottish Youth Parliament (MSYP) I discussed this issue with many young people who believed that ‘Flower of Scotland’ should be officially recognised as Scotland’s national anthem. Also, I have spoken to friends and family members who already think that ‘Flower of Scotland’ is Scotland’s official national anthem, just like many others across Scotland. I have also looked into the history of the Scottish Parliament’s role in recognising a national anthem for Scotland and realise that there has been much demand for Scotland to have an officially recognised national anthem for many years now. This year’s Commonwealth Games in Glasgow showed why ‘Flower of Scotland’ should be recognised as Scotland’s national anthem as the incredible passion of the athletes and spectators singing the song was unbelievable. Also, ‘Flower of Scotland’ is performed with passion before and during football and rugby union matches at Hampden and Murrayfield respectively. I have also looked at many opinions polls regarding an official national anthem for Scotland and these show that ‘Flower of Scotland’ is by far the most popular choice and now is the time to officially recognise it as Scotland’s national anthem. Petition background information ‘Flower of Scotland’ also known as ‘Flùr na h-Alba’ in Scottish Gaelic and ‘Flouer o Scotland’ in Scots is widely recognised as Scotland’s unofficial national anthem. -

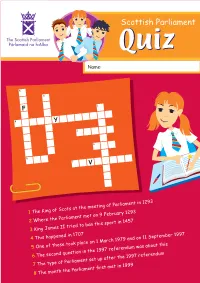

1 the King of Scots at the Meeting of Parliament in 1293 2 Where The

Name: F Y V 1 The King of Scots at the meeting of Parliament in 1293 2 Where the Parliament met on 9 February 1293 3 King James II tried to ban this sport in 1457 4 This happened in 1707 5 One of these took place on 1 March 1979 and on 11 September 1997 6 The second question in the 1997 referendum was about this 7 The type of Parliament set up after the 1997 referendum 8 The month the Parliament first met in 1999 What the Scottish Parliament can do The Scottish Parliament makes decisions that affect matters. our everyday lives and can______________________ pass laws on different things. These are called Some of these matters are: . The Scottish Parliament cannot make laws_________________ on reserved matters. These are dealt with by the Some examples of reserved matters are: The Honours of Scotland The ‘Honours of Scotland’ sculpture was created by silversmith ________________________________. The sculpture was presented to the Scottish Parliament by HM the ______________ to mark the opening of the Scottish Parliament building on Saturday 9 October 200_. The new sculpture is a reminder of the original three Honours of Scotland or the Crown Jewels – the Crown, the Sword and the Sceptre. Label the picture to show the three parts of the ‘Honours’. 1 1 ______________________________________ 2 2 ______________________________________ 3 ______________________________________ 3 What the Scottish Parliament can do The Scottish Parliament makes decisions that affect Passing laws in the Scottish Parliament matters. our everyday lives and can______________________ pass laws on different things. These are called New laws start as a proposal called a B_ _ _ . -

G5 Mysteries Mummy Kids.Pdf

QXP-985166557.qxp 12/8/08 10:00 AM Page 2 This book is dedicated to Tanya Dean, an editor of extraordinary talents; to my daughters, Kerry and Vanessa, and their cousins Doug Acknowledgments and Jessica, who keep me wonderfully “weird;” to the King Family I would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of some of the foremost of Kalamazoo—a minister mom, a radical dad, and two of the cutest mummy experts in the world in creating this book and making it as accurate girls ever to visit a mummy; and to the unsung heroes of free speech— as possible, from a writer’s (as opposed to an expert’s) point of view. Many librarians who battle to keep reading (and writing) a broad-based thanks for the interviews and e-mails to: proposition for ALL Americans. I thank and salute you all. —KMH Dr. Johan Reinhard Dario Piombino-Mascali Dr. Guillermo Cock Dr. Elizabeth Wayland Barber Julie Scott Dr. Victor H. Mair Mandy Aftel Dr. Niels Lynnerup Dr. Johan Binneman Clare Milward Dr. Peter Pieper Dr. Douglas W. Owsley Also, thank you to Dr. Zahi Hawass, Heather Pringle, and James Deem for Mysteries of the Mummy Kids by Kelly Milner Halls. Text copyright their contributions via their remarkable books, and to dozens of others by © 2007 by Kelly Milner Halls. Reprinted by permission of Lerner way of their professional publications in print and online. Thank you. Publishing Group. -KMH PHOTO CREDITS | 5: Mesa Verde mummy © Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, P-605. 7: Chinchero Ruins © Jorge Mazzotti/Go2peru.com. -

That Guy Fae the Corries Ronnie Browne

That Guy Fae the Corries Ronnie Browne Publication Date: 21st January 2016 Format: B paperback ISBN: 9781910985069 Category: Biography RRP: £9.99 Extent: 390 ABOUT THIS BOOK One of the most easily recognised figures on the Scottish scene, Ronnie Browne was one half of The Corries until the untimely death of his musical partner, Roy Williamson, in 1990. He is also a gifted artist, a portraitist of distinction, who has received both critical and commercial success from childhood to the present day. He met his wife, Pat, when they both attended Boroughmuir High School in Edinburgh and formed the most important and enduring partnership of his life, together having three children and four grandchildren. Ronnie Browne writes revealingly of his childhood in pre-War Edinburgh, of The Corrie Folk Trio with Paddy Bell, and The Corries throughout their existence, of the many famous musical personalities he has rubbed shoulders with through the decades, of family, travel and his life as an artist. ‘Likeable because its tone is conversational and confiding, and there are few Scots who have a life SALES AND MARKETING HIGHLIGHTS story like Ronnie Browne’s to confide.’ -The Scots Magazine Follows the highly successful hardback edition published by Sandstone Press in 2015. ‘What unfolds is an incredibly evocative depiction of a young life in post-war Britain, and it is worth ABOUT THE AUTHOR reading the book for his reminiscences of those early days alone.’ Ronnie Browne was born in Edinburgh in 1937 and has lived in or near -Scots Whay Hae the city all through his life.