Ethnic and Language Endangerment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating Land Use and Land Cover Change in the Gaborone Dam Catchment, Botswana, from 1984–2015 Using GIS and Remote Sensing

sustainability Article Evaluating Land Use and Land Cover Change in the Gaborone Dam Catchment, Botswana, from 1984–2015 Using GIS and Remote Sensing Botlhe Matlhodi 1,* , Piet K. Kenabatho 1 , Bhagabat P. Parida 2 and Joyce G. Maphanyane 1 1 Department of Environmental Science, Faculty of Science, University of Botswana, P/Bag UB 00704 Gaborone, Botswana; [email protected] (P.K.K.); [email protected] (J.G.M.) 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, University of Botswana, P/Bag UB 0061 Gaborone, Botswana; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +267-355-5475 Received: 31 May 2019; Accepted: 7 August 2019; Published: 20 September 2019 Abstract: Land use land cover (LULC) change is one of the major driving forces of global environmental change in many developing countries. In this study, LULC changes were evaluated in the Gaborone dam catchment in Botswana between 1984 and 2015. The catchment is a major source of water supply to Gaborone city and its surrounding areas. The study employed Remote Sensing and Geographical Information System (GIS) using Landsat imagery of 1984, 1995, 2005 and 2015. Image classification for each of these imageries was done through supervised classification using the Maximum Likelihood Classifier. Six major LULC categories, cropland, bare land, shrub land, built-up area, tree savanna and water bodies, were identified in the catchment. It was observed that shrub land and tree savanna were the major LULC categories between 1984 and 2005 while shrub land and cropland dominated the catchment area in 2015. The rates of change were generally faster in the 1995–2005 and 2005–2015 periods. -

Title of Your Article

Vol. 11, No. 2 International Journal of Multicultural Education 2009 Monocultural Education in a Multicultural Society: The case of Teacher Preparation in Botswana Annah Anikie Molosiwa The University of Botswana Botswana In several policy documents reviewing the country’s education system, the Ministry of Education has made noteworthy pronouncements on how to improve teacher education in Botswana. This mainly concerns equipping teachers with pedagogical skills to better address the learning needs of the linguistically and culturally diverse student population. Even though at policy level it is acknowledged that Botswana is a multicultural society, at implementation stage there is no such evidence. This article argues that lack of implementation of policy pronouncements contradicts the government’s aspirations to provide equal learning opportunity to all learners. The infusion of courses in multicultural education at teacher education level is seen as an alternative. Introduction Geography and Language Description of Language Education Programs Literature Review Policy Pronouncements on Teacher Education Conclusion Notes References Introduction While the government of Botswana has made resources available to support the education of teachers, attempts to prepare teachers with the skills to better address the learning needs of the linguistically and culturally diverse student population in schools still remains inadequate. This contradicts the country‟s aspirations to provide equal educational opportunity to all citizens by the year 2016 (Republic of Botswana, 1997). The aim to increase access and equity at primary and secondary school levels and to improve the quality of education is pronounced in many policy documents such as the 1994 Revised National Policy on Education (RNPE) and Vision 2016 Report. -

Voicing on the Fringe: Towards an Analysis of ‘Quirkyʼ Phonology in Ju and Beyond

Voicing on the fringe: towards an analysis of ‘quirkyʼ phonology in Ju and beyond Lee J. Pratchett Abstract The binary voice contrast is a productive feature of the sound systems of Khoisan languages but is especially pervasive in Ju (Kx’a) and Taa (Tuu) in which it yields phonologically contrastive segments with phonetically complex gestures like click clusters. This paper investigates further the stability of these ‘quirky’ segments in the Ju language complex in light of new data from under-documented varieties spoken in Botswana that demonstrate an almost systematic devoicing of such segments, pointing to a sound change in progress in varieties that one might least expect. After outlining a multi-causal explanation of this phenomenon, the investigation shifts to a diachronic enquiry. In the spirit of Anthony Traill (2001), using the most recent knowledge on Khoisan languages, this paper seeks to unveil more on language history in the Kalahari Basin Area from these typologically and areally unique sounds. Keywords: Khoisan, historical linguistics, phonology, Ju, typology (AFRICaNa LINGUISTICa 24 (2018 100 Introduction A phonological voice distinction is common to more than two thirds of the world’s languages: whilst largely ubiquitous in African languages, a voice contrast is almost completely absent in the languages of Australia (Maddison 2013). The particularly pervasive voice dimension in Khoisan1 languages is especially interesting for two reasons. Firstly, the feature is productive even with articulatory complex combinations of clicks and other ejective consonants, gestures that, from a typological perspective, are incompatible with the realisation of voicing. Secondly, these phonological contrasts are robustly found in only two unrelated languages, Taa (Tuu) and Ju (Kx’a) (for a classification see Güldemann 2014). -

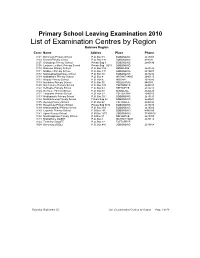

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

Identity and Plurilinguism in Africa – the Case of Mozambique

IDENTITY AND PLURILINGUISM IN AFRICA – THE CASE OF MOZAMBIQUE IDENTIDADE E PLURILINGUISMO NA ÁFRICA: O CASO DE MOÇAMBIQUE Sarita Monjane HENRIKSEN Universidade Pedagógica Mozambique International Abstract: The African continent is a true ethnic-linguistic and cultural mosaic, composed of 55 countries and characterised by the existence of approximately 2.000 languages and a large number of ethnic groups. Mozambique in the extreme south of the continent does not escape from this rule. The country, with its approximately 25 million inhabitants is characterised by a significantly high ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity. In spite of this superdiversity it is possible to talk about an African identity and surely a Mozambican identity. The present study describes ethnic and cultural diversity in Africa, focusing on issues of plurilingualism or multilingualism in the continent. In addition, the study deals particularly with Mozambique’s ethnolinguistic landscape, discussing the importance of preserving diversity and lastly it presents a number of considerations on those factors that contribute to the construction of national identity and to the development of our Mozambicaness in this Indian Ocean country. Ke ywords: Identity, Plurilingualism, Ethnic-Linguistic and Cultural Diversity and Superdiversity Resumo: O continente africano é um verdadeiro mosaico étnico-linguístico e cultural, composto por 55 países e caracterizado pela existência de aproximadamente 2.000 línguas e inúmeros grupos étnicos. Moçambique no extremo sul deste continente não escapa a esta regra. O país, com os seus cerca de 25 milhões de habitantes é também caracterizado por uma significante diversidade étnica, linguística e cultural. Apesar desta superdiversidade é possível falar sobre uma identidade africana e uma identidade moçambicana. -

New List of Archaeologists 2019.Pdf

P Department of National Museum Monument and Art Gallery 331 Independence Avenue Gaborone, Botswana Private Bag 00114 Tel: (267) 3974616 (267) 3610400 Fax: (267) 3902797 Email: [email protected] Website: www.national- museum.gov.bw A LIST OF APPROVED ARCHAEOLOGISTS 2019 Our reference Dr Alfred Tsheboeng Dr Alinah Segobye P.O. Box 2789 University of Botswana Gaborone International Finance Park P/Bag 0022, Gaborone Plot 128,Kgale Court, Unit 8, Gaborone Tel: 3162036 Cel: 71374291 Tel: 3552281 Cel: 71625018 e-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Catrien Van Waarden Dr Nick Walker Marope Research Achilles Investments Pty Ltd P.O. Box 910, Francistown Gaborone Tel: 2414257 Cell: 71378415 Email: [email protected] [email protected] P. Sekgarametso-Modikwa Pena Monageng Archaeological Resources Management Services Ditso Archaeological Surveys P.O. Box 601271 P/Bag 0029, suit no 285 Gaborone Postnet Mogoditshane Tel: 3922289 cell: 71653378 Tel: 3552267 Cell: 71728860 Fax: 3922289 Fax: 3938757 Email: [email protected] Mr. O.J. NOKO Mr. Donald Mookodi Crystal Touch (Pty) Ltd Geoarch Investment Pty Ltd Postnet Kgale View P.O. Box 10111 P/Bag 351 suite 418 Gaborone Gaborone, Botswana Tel: (5442552 Cell: 71710397 Cell: 72202884 Fax: 3975566 Email: [email protected]/ 1 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Mr. Oscar Motsumi Nyatsego L. Baeletsi Watershed (Pty) Ltd Kgato-Go-Ya-Pele (Pty) Ltd P.O. Box 3347 P.O. Box 202850 Gaborone, Botswana Gaborone Tel: (09267) 316400/3699840 Tel/Fax: 3185133 Cel: 71676356 Cel: (09267) 71313089/74222285 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] motsumio@botsnet-bw Dr Susan O. -

Haina-Kalahari-Lodge-Directions.Pdf

DIRECTIONS GPS CO-ORDINATES Main Gate: Lodge: S 21° 00.006’ S 20° 56.966’ E 023° 41.085’ E 023° 40.684’ Campsite: Airfield: S 20° 59.310’ S 20° 57.081’ E 023° 41.905’ E 023° 40.209’ CONTACT DETAILS Lodge Phone: +267 683 0238 Email: [email protected] Reservations Phone: +27 21 421 8433 Website: www.haina.co.za HAINA KALAHARI LODGE From Maun towards Mopipi. The road passes Mopipi and carries Take the main road to Nata – turn right at about on towards Rakops. 23km past the police station at 50km out of Maun towards Makalamabedi. Drive on Rakops turn left on a dirt road, here you will find a sign for 18km (mind the sharp right crossing the Boteti board Haina Kalahari Lodge (please don’t turn left at river!) to the Vet fence gate. Go through the fence the signboard for the Central Kalahari Game Reserve and turn directly right (90 deg.) onto the cut line which is only about 5km past the police station). running South (mind the curb – take a wide turn). Carry on with this dirt road, after +/- 45km you will Continue on the cut line for 70 odd km and turn right find a gate this is Pfefodiafoka (some people refer again entering the gate at Kuke corner. #Take the to this gate as the Kuke Corner). Sign the register small loop around and drive west along the Northern and pass through the Pfefodiafoka Corner Veterinary border on CKGR for 20km. There is a sign for Haina Gate almost 20km, with the veterinary fence on you on the right. -

A Bottom-Up Approach to Language Education Policy in Mozambique Henriksen, Sarita Monjane

Roskilde University Language attitudes in a primary school a bottom-up approach to language education policy in Mozambique Henriksen, Sarita Monjane Publication date: 2010 Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Henriksen, S. M. (2010). Language attitudes in a primary school: a bottom-up approach to language education policy in Mozambique. Roskilde Universitet. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Oct. 2021 RRoosskkiillddee UUnniivveerrssiittyy DDeeppaarrttmmeenntt ooff CCuullttuurree aanndd IIddeennttiittyy Language Attitudes in a Primary School: A Bottom-Up Approach to Language Education Policy in Mozambique Sarita Monjane Henriksen 31-08-2010 LANGUAGE ATTITUDES IN A PRIMARY SCHOOL: A BOTTOM-UP APPROACH TO 31. august 2010 LANGUAGE EDUCATION POLICY IN MOZAMBIQUE RRoosskkiillddee UUnniivveerrssiittyy DDeeppaarrttmmeenntt ooff CCuullttuurree aanndd IIddeennttiittyy LLaanngguuaaggee AAttttiittuuddeess iinn aa PPrriimmaarryy SScchhooooll:: AA BBoottttoomm--UUpp AApppprrooaacchh ttoo LLaanngguuaaggee EEdduuccaattiioonn PPoolliiccyy iinn MMoozzaammbbiiqquuee SSaarriiitttaa MMoonnjjjaannee HHeennrriiikksseenn 2 LANGUAGE ATTITUDES IN A PRIMARY SCHOOL: A BOTTOM-UP APPROACH TO 31. -

List of Schools Visited for Monitoring Visits

LIST OF SCHOOLS VISITED FOR MONITORING VISITS CENTRAL INSPECTORAL AREA LOCATION NAME OF SCHOOL MMADINARE Diloro Diloro MMADINARE Mmadinare Kelele MMADINARE Kgagodi Kgagodi MMADINARE Mmadinare Mmadinare MMADINARE Mmadinare Phethu Mphoeng MMADINARE Robelela Robelela MMADINARE Gojwane Sedibe MMADINARE Serule Serule MMADINARE Mmadinare Tlapalakoma BOTETI Rakops Etsile BOTETI Khumaga Khumaga BOTETI Khwee Khwee BOTETI Mopipi Manthabakwe BOTETI Mmadikola Mmadikola BOTETI Letlhakane Mokane BOTETI Mokoboxane Mokoboxane BOTETI Mokubilo Mokubilo BOTETI Moreomaoto Moreomaoto BOTETI Mosu Mosu BOTETI Motlopi Motlopi BOTETI Letlhakane Retlhatloleng Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Boitshoko Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Boswelakgomo Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Selibe Phikwe Tebogo BOBIRWA Bobonong Bobonong BOBIRWA Gobojango Gobojango BOBIRWA Bobonong Mabumahibidu BOBIRWA Bobonong Madikwe BOBIRWA Mogapi Mogapi BOBIRWA Molalatau Molalatau BOBIRWA Bobonong Rasetimela BOBIRWA Semolale Semolale BOBIRWA Tsetsebye Tsetsebye 1 | P a g e MAHALAPYE WEST Bonwapitse Bonwapitse MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye Leetile MAHALAPYE WEST Mokgenene Mokgenene MAHALAPYE WEST Moralane Moralane MAHALAPYE WEST Mosolotshane Mosolotshane MAHALAPYE WEST Otse Setlhamo MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye St James MAHALAPYE WEST Mahalapye Tshikinyega MHALAPYE EAST Mahalapye Flowertown MHALAPYE EAST Mahalapye Mahalapye MHALAPYE EAST Matlhako Matlhako MHALAPYE EAST Mmaphashalala Mmaphashalala MHALAPYE EAST Sefhare Mmutle PALAPYE NORTH Goo-Sekgweng Goo-Sekgweng PALAPYE NORTH Goo-Tau Goo-Tau -

SABONET Report No 18

ii Quick Guide This book is divided into two sections: the first part provides descriptions of some common trees and shrubs of Botswana, and the second is the complete checklist. The scientific names of the families, genera, and species are arranged alphabetically. Vernacular names are also arranged alphabetically, starting with Setswana and followed by English. Setswana names are separated by a semi-colon from English names. A glossary at the end of the book defines botanical terms used in the text. Species that are listed in the Red Data List for Botswana are indicated by an ® preceding the name. The letters N, SW, and SE indicate the distribution of the species within Botswana according to the Flora zambesiaca geographical regions. Flora zambesiaca regions used in the checklist. Administrative District FZ geographical region Central District SE & N Chobe District N Ghanzi District SW Kgalagadi District SW Kgatleng District SE Kweneng District SW & SE Ngamiland District N North East District N South East District SE Southern District SW & SE N CHOBE DISTRICT NGAMILAND DISTRICT ZIMBABWE NAMIBIA NORTH EAST DISTRICT CENTRAL DISTRICT GHANZI DISTRICT KWENENG DISTRICT KGATLENG KGALAGADI DISTRICT DISTRICT SOUTHERN SOUTH EAST DISTRICT DISTRICT SOUTH AFRICA 0 Kilometres 400 i ii Trees of Botswana: names and distribution Moffat P. Setshogo & Fanie Venter iii Recommended citation format SETSHOGO, M.P. & VENTER, F. 2003. Trees of Botswana: names and distribution. Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report No. 18. Pretoria. Produced by University of Botswana Herbarium Private Bag UB00704 Gaborone Tel: (267) 355 2602 Fax: (267) 318 5097 E-mail: [email protected] Published by Southern African Botanical Diversity Network (SABONET), c/o National Botanical Institute, Private Bag X101, 0001 Pretoria and University of Botswana Herbarium, Private Bag UB00704, Gaborone. -

The Marginalisation of Tonga in the Education System in Zimbabwe

THE MARGINALISATION OF TONGA IN THE EDUCATION SYSTEM IN ZIMBABWE BY PATRICK NGANDINI UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA NOVEMBER 2016 THE MARGINALISATION OF TONGA IN THE EDUCATION SYSTEM IN ZIMBABWE BY PATRICK NGANDINI Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY In the subject AFRICAN LANGUAGES at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: Professor D. E. Mutasa Co – Promoter: Professor M. L. Mojapelo November 2016 Declaration STUDENT NUMBER: 53259955 I, Patrick Ngandini, declare that THE MARGINALISATION OF TONGA IN THE EDUCATION SYSTEM IN ZIMBABWE is my own work and that the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. November 2016 Signature Date (PATRICK NGANDINI) i Dedication To my lovely wife Jesca Benza Ngandini, and my four children, Wadzanai Ashley, Rutendo Trish, Masimba and Wedzerai Faith. This thesis is also dedicated to my late father Simon Tsvetai Ngandini and my late mother Emilly Chamwada Maposa Ngandini who were my pillars throughout the painful process of my education. ii List of tables Table 2:1 Continental number of languages .......................................................................... 21 Table 2:2 Linguistic profile of Botswana............................................................................... 35 Table 4:2 Sample of the population ..................................................................................... 108 Table 5:1 Clauses from the Secretary‘s Circular No. 3 of 2002 .......................................... -

Firewood Utilisation and Its Implication on Trees Around Mopipi Village in Boteti Sub-District of Botswana

Asian Journal of Environment & Ecology 7(2): 1-10, 2018; Article no.AJEE.42471 ISSN: 2456-690X Firewood Utilisation and Its Implication on Trees around Mopipi Village in Boteti Sub-District of Botswana Wanda N. Mphinyane1*, Lawrence K. Akanyang2, Kutlwano Mulale1, Fritz Van Deventer3, Lapologang Magole4, Jeremy S. Perkins1, Reuben J. Sebego1, Julius R. Atlhopheng1 and Raban Chanda1 1Department of Environmental Science, Faculty of Science, Private Bag UB 00704, Gaborone, Botswana. 2Botswana College of Agriculture, Private Bag 0027, Gaborone, Botswana. 3Department of Land and Water Management, Wageningen University, Netherlands. 4Okavango Research Institute, Private Bag 285, Maun, Botswana. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Authors WNM, LKA, JRA and RC designed the study. Authors WNM, LKA, KM, FVD and LM participated in field investigation, data collection and authors WNM, LKA, KM and FVD performed the statistical analysis. Authors RJS and JSP managed the literature searches and analyses of the study. Author WNM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/AJEE/2018/42471 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Onofre S. Corpuz, CFCST-Doroluman Arakan 9417 Cotabato, Philippines. (2) Dr. Daniele De Wrachien, Professor, Agricultural Hydraulics at the Department of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, State University of Milan, Italy. Reviewers: (1) Kokou Kouami, Université de Lomé, Togo. (2) T. O. Adewuyi, Nigerian Defence