ESID Working Paper No. 113 Political Settlements and the Delivery Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gomba District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi Le

Gomba District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 GOMBA DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE a Acknowledgment On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Mr. Ogwang Jimmy, Disaster Preparedness Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred-Early Warning system Programmer. My appreciation also goes to Gomba District Team. The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees GOMBA DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The multi-hazard vulnerability profile outputs from this assessment for Gomba District was a combination of spatial modeling using adaptive, sensitivity and exposure spatial layers and information captured from District Key Informant interviews and sub-county FGDs using a participatory approach. -

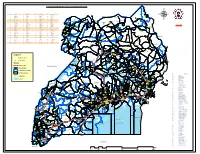

UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details)

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details) SUDAN NARENGEPAK KARENGA KATHILE KIDEPO NP !( NGACINO !( LOPULINGI KATHILE AGORO AGU FR PABAR AGORO !( !( KAMION !( Apoka TULIA PAMUJO !( KAWALAKOL RANGELAND ! KEI FR DIBOLYEC !( KERWA !( RUDI LOKWAKARAMOE !( POTIKA !( !( PAWACH METU LELAPWOT LAWIYE West PAWOR KALAPATA MIDIGO NYAPEA FR LOKORI KAABONG Moyo KAPALATA LODIKO ELENDEREA PAJAKIRI (! KAPEDO Dodoth !( PAMERI LAMWO FR LOTIM MOYO TC LICWAR KAPEDO (! WANDI EBWEA VUURA !( CHAKULYA KEI ! !( !( !( !( PARACELE !( KAMACHARIKOL INGILE Moyo AYUU POBURA NARIAMAOI !( !( LOKUNG Madi RANGELAND LEFORI ALALI OKUTI LOYORO AYIPE ORAA PAWAJA Opei MADI NAPORE MORUKORI GWERE MOYO PAMOYI PARAPONO ! MOROTO Nimule OPEI PALAJA !( ALURU ! !( LOKERUI PAMODO MIGO PAKALABULE KULUBA YUMBE PANGIRA LOKOLIA !( !( PANYANGA ELEGU PADWAT PALUGA !( !( KARENGA !( KOCHI LAMA KAL LOKIAL KAABONG TEUSO Laropi !( !( LIMIDIA POBEL LOPEDO DUFILE !( !( PALOGA LOMERIS/KABONG KOBOKO MASALOA LAROPI ! OLEBE MOCHA KATUM LOSONGOLO AWOBA !( !( !( DUFILE !( ORABA LIRI PALABEK KITENY SANGAR MONODU LUDARA OMBACHI LAROPI ELEGU OKOL !( (! !( !( !( KAL AKURUMOU KOMURIA MOYO LAROPI OMI Lamwo !( KULUBA Koboko PODO LIRI KAL PALORINYA DUFILE (! PADIBE Kaabong LOBONGIA !( LUDARA !( !( PANYANGA !( !( NYOKE ABAKADYAK BUNGU !( OROM KAABONG! TC !( GIMERE LAROPI PADWAT EAST !( KERILA BIAFRA !( LONGIRA PENA MINIKI Aringa!( ROMOGI PALORINYA JIHWA !( LAMWO KULUYE KATATWO !( PIRE BAMURE ORINJI (! BARINGA PALABEK WANGTIT OKOL KINGABA !( LEGU MINIKI -

Roads in Sembabule District; Most Especially Those Connecting to Other Districts

STATEMENT PRESENTED BY HON. MINISTER OF WORKS AND TRANSPORT TO PARLIAMENT OF UGANDA IN RESPONSE TO A QUESTION RAISED BY HON. BANGIRANA KAWOOYA ANIFA, WOMAN MP FOR SEMBABULE DISTRICT CONCERNING THE DEPLORABLE STATE OF ROADS IN SEMBABULE DISTRICT; MOST ESPECIALLY THOSE CONNECTING TO OTHER DISTRICTS Rt. Hon. Speaker and Hon. Members, This statement is presented in response to a matter raised at the 9th sitting of the 1st meeting of the 4th session of the 1Oth Parliament by Hon. Bangirana Kawooya Anifa, Woman MP for Sembabule District concerning the deplorable state of roads in Sembabule district. The Ministry of Works and Transport through Uganda National Road Authority (UNRA), the Uganda Road Fund (URF) and the District Local Governments continues to implement road construction projects and maintenance activities. ln Sembabule district the following projects are being undertaken; (i) The Upgrading of Kanoni - Sembabule and Sembabule - Villa Maria (110km): This project starts in Kanoni in Mpigi district through to Sembabule and Villa Maria and involves upgrading the existing gravel road to paved (tarmac). Road works commenced in September 2014 and substantially completed in June 2019. (ii) Upgrading of Lusalira-Nkonge-Sembabule (97km): This Road is under procurement as part of the Critical Oil Roads development programme. The contract is expected to be signed in August 2019. (iii) Term, Framework and Periodic Maintenance of Roads: UNRA is undertaking term, framework and periodic maintenance within Sembabule \ 7 t I District which will significantly improve the state of roads in the district. This will be done through the following lots; a Term Maintenance of 14 selected National roads Phase Vll. -

FY 2019/20 Vote:551 Sembabule District

LG Approved Workplan Vote:551 Sembabule District FY 2019/20 Foreword 6HPEDEXOH'LVWULFW'UDIW%XGJHW(VWLPDWHV$QQXDO:RUNSODQVDQG3HUIRUPDQFH&RQWUDFWIRU2019/2020 manifests compliance to the legal requirement by PFMA 2015 and the Local Government Act Cap 243 as ammended, that mandates the Accounting Officer to prepare the Budget Estimates and plans for the District and have it laid before Council by the 31st of March of every financial year . The Local Government Act CAP 243 section 35, sub section (3) empowers the District Council as the planning authority of the District. Sembabule District Local Government thus recognizes the great importance attached to the production of the for Draft Budget Estimates the District which guides the budgeting process, identifies the key priority areas of the second 5 year NDP 2015/2016-2019/2020DQGWKDWRI6HPEDEXOH2nd five year DDP (2015/2016 - 2019/2020). The execution of the budget is expected to greatly improve service delivery and thus the livelihood of the populace in the District. The 2019/2020 budget process started with the regional budget consultative workshops that were held mid September 2018. A number of consultative meetings involving various stakeholders took place including the District Conference which was held on 8th November 2018 to prioritize, areas of intervention in the financial year 2019/2020,this was follwed by the production of the BFP which was submitted to MOFPED on 13th November 2018. The District shall comply with reforms of physical transfers guided by the MoFPED that are geared towards improved financial management service delivery and accountability. However, Sembabule District still faces a challenge of funding the nine newly created and sworn in Lower Local Governments of Nakasenyi, Katwe, Mitima, Bulongo, Kawanda, Nabitanga, Mabindo kyera and Ntuusi Town Council. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Population by Parish

Total Population by Sex, Total Number of Households and proportion of Households headed by Females by Subcounty and Parish, Central Region, 2014 District Population Households % of Female Males Females Total Households Headed HHS Sub-County Parish Central Region 4,672,658 4,856,580 9,529,238 2,298,942 27.5 Kalangala 31,349 22,944 54,293 20,041 22.7 Bujumba Sub County 6,743 4,813 11,556 4,453 19.3 Bujumba 1,096 874 1,970 592 19.1 Bunyama 1,428 944 2,372 962 16.2 Bwendero 2,214 1,627 3,841 1,586 19.0 Mulabana 2,005 1,368 3,373 1,313 21.9 Kalangala Town Council 2,623 2,357 4,980 1,604 29.4 Kalangala A 680 590 1,270 385 35.8 Kalangala B 1,943 1,767 3,710 1,219 27.4 Mugoye Sub County 6,777 5,447 12,224 3,811 23.9 Bbeta 3,246 2,585 5,831 1,909 24.9 Kagulube 1,772 1,392 3,164 1,003 23.3 Kayunga 1,759 1,470 3,229 899 22.6 Bubeke Sub County 3,023 2,110 5,133 2,036 26.7 Bubeke 2,275 1,554 3,829 1,518 28.0 Jaana 748 556 1,304 518 23.0 Bufumira Sub County 6,019 4,273 10,292 3,967 22.8 Bufumira 2,177 1,404 3,581 1,373 21.4 Lulamba 3,842 2,869 6,711 2,594 23.5 Kyamuswa Sub County 2,733 1,998 4,731 1,820 20.3 Buwanga 1,226 865 2,091 770 19.5 Buzingo 1,507 1,133 2,640 1,050 20.9 Maziga Sub County 3,431 1,946 5,377 2,350 20.8 Buggala 2,190 1,228 3,418 1,484 21.4 Butulume 1,241 718 1,959 866 19.9 Kampala District 712,762 794,318 1,507,080 414,406 30.3 Central Division 37,435 37,733 75,168 23,142 32.7 Bukesa 4,326 4,711 9,037 2,809 37.0 Civic Centre 224 151 375 161 14.9 Industrial Area 383 262 645 259 13.9 Kagugube 2,983 3,246 6,229 2,608 42.7 Kamwokya -

Funding Going To

% Funding going to Funding Country Name KP‐led Timeline Partner Name Sub‐awardees SNU1 PSNU MER Structural Interventions Allocated Organizations HTS_TST Quarterly stigma & discrimination HTS_TST_NEG meetings; free mental services to HTS_TST_POS KP clients; access to legal services PrEP_CURR for KP PLHIV PrEP_ELIGIBLE Centro de Orientacion e PrEP_NEW Dominican Republic $ 1,000,000.00 88.4% MOSCTHA, Esperanza y Caridad, MODEMU Region 0 Distrito Nacional Investigacion Integral (COIN) PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_NEW TX_PVLS (D) TX_PVLS (N) TX_RTT Gonaives HTS_TST KP sensitization focusing on Artibonite Saint‐Marc HTS_TST_NEG stigma & discrimination, Nord Cap‐Haitien HTS_TST_POS understanding sexual orientation Croix‐des‐Bouquets KP_PREV & gender identity, and building Leogane PrEP_CURR clinical providers' competency to PrEP_CURR_VERIFY serve KP FY19Q4‐ KOURAJ, ACESH, AJCCDS, ANAPFEH, APLCH, CHAAPES, PrEP_ELIGIBLE Haiti $ 1,000,000.00 83.2% FOSREF FY21Q2 HERITAGE, ORAH, UPLCDS PrEP_NEW Ouest PrEP_NEW_VERIFY Port‐au‐Prince PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_CURR_VERIFY TX_NEW TX_NEW_VERIFY Bomu Hospital Affiliated Sites Mombasa County Mombasa County not specified HTS_TST Kitui County Kitui County HTS_TST_NEG CHS Naishi Machakos County Machakos County HTS_TST_POS Makueni County Makueni County KP_PREV CHS Tegemeza Plus Muranga County Muranga County PrEP_CURR EGPAF Timiza Homa Bay County Homa Bay County PrEP_CURR_VERIFY Embu County Embu County PrEP_ELIGIBLE Kirinyaga County Kirinyaga County HWWK Nairobi Eastern PrEP_NEW Tharaka Nithi County Tharaka Nithi County -

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Ssembabule Constituency: 119 Lwemiyaga County

Printed on: Monday, January 18, 2021 14:33:40 PM PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS, (Presidential Elections Act, 2005, Section 48) RESULTS TALLY SHEET DISTRICT: 045 SSEMBABULE CONSTITUENCY: 119 LWEMIYAGA COUNTY Parish Station Reg. AMURIAT KABULETA KALEMBE KATUMBA KYAGULA MAO MAYAMBA MUGISHA MWESIGYE TUMUKUN YOWERI Valid Invalid Total Voters OBOI KIIZA NANCY JOHN NYI NORBERT LA WILLY MUNTU FRED DE HENRY MUSEVENI Votes Votes Votes PATRICK JOSEPH LINDA SSENTAMU GREGG KAKURUG TIBUHABU ROBERT U RWA KAGUTA Sub-county: 001 LWEMIYAGA 002 LWEMIBU 01 LWEMIYAGA 829 1 0 1 2 255 0 0 1 0 0 181 441 5 446 0.23% 0.00% 0.23% 0.45% 57.82% 0.00% 0.00% 0.23% 0.00% 0.00% 41.04% 1.12% 53.80% 02 KAKOMBE 493 0 0 0 1 53 0 0 2 0 1 179 236 3 239 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.42% 22.46% 0.00% 0.00% 0.85% 0.00% 0.42% 75.85% 1.26% 48.48% 03 LUMEGERE 406 0 0 1 0 44 0 1 0 0 0 203 249 7 256 0.00% 0.00% 0.40% 0.00% 17.67% 0.00% 0.40% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 81.53% 2.73% 63.05% 04 KASHUNGA TRADING 416 0 0 0 0 34 0 0 0 0 0 184 218 2 220 CENTRE 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 15.60% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 84.40% 0.91% 52.88% 05 KIWANGIRE TRADING 346 0 0 0 0 48 1 0 0 0 0 126 175 4 179 CENTRE 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 27.43% 0.57% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 72.00% 2.23% 51.73% 06 LWEMIBU A 291 0 0 0 0 23 0 0 0 0 1 120 144 1 145 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 15.97% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.69% 83.33% 0.69% 49.83% 07 TANGIRIZA 255 0 0 0 0 88 0 0 0 0 0 85 173 12 185 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 50.87% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 49.13% 6.49% 72.55% Parish Total 3036 1 0 2 3 545 1 1 3 0 2 1078 1636 34 1670 0.06% 0.00% -

Ministry of Lands,Housing and Urban Development.Pdf

Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 012 Ministry of Lands, Housing & Urban Development Structure of Submission QUARTER 3 Performance Report Summary of Vote Performance Cumulative Progress Report for Projects and Programme Quarterly Progress Report for Projects and Programmes QUARTER 4: Workplans for Projects and Programmes Submission Checklist Page 1 Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 012 Ministry of Lands, Housing & Urban Development QUARTER 3: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution This section provides an overview of Vote expenditure (i) Snapshot of Vote Releases and Expenditures Table V1.1 below summarises cumulative releases and expenditures by the end of the quarter: Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases (i) Excluding Arrears, Taxes Budget by End by End End Mar Released Spent Spent Wage 3.386 3.098 3.098 3.022 91.5% 89.3% 97.6% Recurrent Non Wage 13.648 6.198 9.897 9.228 72.5% 67.6% 93.2% GoU 38.570 13.210 13.210 9.285 34.2% 24.1% 70.3% Development Donor* 25.048 N/A 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% N/A GoU Total 55.604 22.506 26.204 21.535 47.1% 38.7% 82.2% Total GoU+Donor (MTEF) 80.651 N/A 26.204 21.535 32.5% 26.7% 82.2% Arrears 0.116 N/A 0.116 0.116 99.8% 99.7% 99.9% (ii) Arrears and Taxes Taxes** 0.000 N/A 0.000 0.000 N/A N/A N/A Total Budget 80.768 22.506 26.320 21.651 32.6% 26.8% 82.3% (iii) Non Tax Revenue 1.330 N/A 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% N/A Grand Total 82.098 -

Vote: 551 Sembabule District Structure of Workplan

Local Government Workplan Vote: 551 Sembabule District Structure of Workplan Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2015/16 D: Details of Annual Workplan Activities and Expenditures for 2015/16 Page 1 Local Government Workplan Vote: 551 Sembabule District Foreword Sembabule became a District in 1997. It has two counties – Lwemiyaga with ntuusi and Lwemiyaga Sub Counties and Mawogala with Mateete Town council, Sembabule Town council and Mateete, Lwebitakuli, Mijwala and Lugusulu sub counties hence eight lower local governments. In line with the Local Government Act 1997 CAP 243, which mandates the District with the authority to plan for the Local Governments, this Budget for the Financial Year 2014-2015 has been made comprising of; The Forward, Executive Summary, and a) Revenue Peformance and Pans, b) Summary of Departmental Performance and Plans by Work plan and c) Approved Annual Work plan Outputs for 2014-2015 which have been linked to the Medium Expenditure Plan and the District Development Plan 1011-2015. and this time the District staff list. We hope this will enable elimination of ghost workers and salary payments by 28th of every month. In line with the above, the Budget is the guide for giving an insight to the district available resources and a guide to attach them to priority areas that serve the needs of the people of Sembabule District in order to improve on their standard of living with more focus to the poor, women, youth, the elderly and people with disabilities (PWDs) although not neglecting the middle income and other socioeconomic denominations by providing improver Primary health care services, Pre Primary, Primary, secondary and tertiary Education, increasing agriculture productivity by giving farm inputs and advisory services and provision of infrastructure mainly in roads and water sectors among others .