Factors Affecting Girl Child Education in Ntuusi Sub-County, Sembabule District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gomba District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi Le

Gomba District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 GOMBA DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE a Acknowledgment On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Mr. Ogwang Jimmy, Disaster Preparedness Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred-Early Warning system Programmer. My appreciation also goes to Gomba District Team. The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees GOMBA DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The multi-hazard vulnerability profile outputs from this assessment for Gomba District was a combination of spatial modeling using adaptive, sensitivity and exposure spatial layers and information captured from District Key Informant interviews and sub-county FGDs using a participatory approach. -

FY 2019/20 Vote:551 Sembabule District

LG Approved Workplan Vote:551 Sembabule District FY 2019/20 Foreword 6HPEDEXOH'LVWULFW'UDIW%XGJHW(VWLPDWHV$QQXDO:RUNSODQVDQG3HUIRUPDQFH&RQWUDFWIRU2019/2020 manifests compliance to the legal requirement by PFMA 2015 and the Local Government Act Cap 243 as ammended, that mandates the Accounting Officer to prepare the Budget Estimates and plans for the District and have it laid before Council by the 31st of March of every financial year . The Local Government Act CAP 243 section 35, sub section (3) empowers the District Council as the planning authority of the District. Sembabule District Local Government thus recognizes the great importance attached to the production of the for Draft Budget Estimates the District which guides the budgeting process, identifies the key priority areas of the second 5 year NDP 2015/2016-2019/2020DQGWKDWRI6HPEDEXOH2nd five year DDP (2015/2016 - 2019/2020). The execution of the budget is expected to greatly improve service delivery and thus the livelihood of the populace in the District. The 2019/2020 budget process started with the regional budget consultative workshops that were held mid September 2018. A number of consultative meetings involving various stakeholders took place including the District Conference which was held on 8th November 2018 to prioritize, areas of intervention in the financial year 2019/2020,this was follwed by the production of the BFP which was submitted to MOFPED on 13th November 2018. The District shall comply with reforms of physical transfers guided by the MoFPED that are geared towards improved financial management service delivery and accountability. However, Sembabule District still faces a challenge of funding the nine newly created and sworn in Lower Local Governments of Nakasenyi, Katwe, Mitima, Bulongo, Kawanda, Nabitanga, Mabindo kyera and Ntuusi Town Council. -

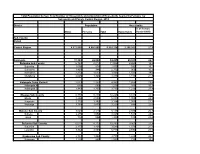

Population by Parish

Total Population by Sex, Total Number of Households and proportion of Households headed by Females by Subcounty and Parish, Central Region, 2014 District Population Households % of Female Males Females Total Households Headed HHS Sub-County Parish Central Region 4,672,658 4,856,580 9,529,238 2,298,942 27.5 Kalangala 31,349 22,944 54,293 20,041 22.7 Bujumba Sub County 6,743 4,813 11,556 4,453 19.3 Bujumba 1,096 874 1,970 592 19.1 Bunyama 1,428 944 2,372 962 16.2 Bwendero 2,214 1,627 3,841 1,586 19.0 Mulabana 2,005 1,368 3,373 1,313 21.9 Kalangala Town Council 2,623 2,357 4,980 1,604 29.4 Kalangala A 680 590 1,270 385 35.8 Kalangala B 1,943 1,767 3,710 1,219 27.4 Mugoye Sub County 6,777 5,447 12,224 3,811 23.9 Bbeta 3,246 2,585 5,831 1,909 24.9 Kagulube 1,772 1,392 3,164 1,003 23.3 Kayunga 1,759 1,470 3,229 899 22.6 Bubeke Sub County 3,023 2,110 5,133 2,036 26.7 Bubeke 2,275 1,554 3,829 1,518 28.0 Jaana 748 556 1,304 518 23.0 Bufumira Sub County 6,019 4,273 10,292 3,967 22.8 Bufumira 2,177 1,404 3,581 1,373 21.4 Lulamba 3,842 2,869 6,711 2,594 23.5 Kyamuswa Sub County 2,733 1,998 4,731 1,820 20.3 Buwanga 1,226 865 2,091 770 19.5 Buzingo 1,507 1,133 2,640 1,050 20.9 Maziga Sub County 3,431 1,946 5,377 2,350 20.8 Buggala 2,190 1,228 3,418 1,484 21.4 Butulume 1,241 718 1,959 866 19.9 Kampala District 712,762 794,318 1,507,080 414,406 30.3 Central Division 37,435 37,733 75,168 23,142 32.7 Bukesa 4,326 4,711 9,037 2,809 37.0 Civic Centre 224 151 375 161 14.9 Industrial Area 383 262 645 259 13.9 Kagugube 2,983 3,246 6,229 2,608 42.7 Kamwokya -

Press Release

t The Reoublic of LJoanda MINISTRY OF HEALTH Office of the Director General 'Public Relations Unit 256-41 -4231 584 D i rector Gen era l's Off ice : 256- 41 4'340873 Fax : PRESS RELEASE IMPLEMENTATION OF HEPATITIS B CONTROL ACTIVITIES IN I(AMPALA METROPOLITAN AREA Kampala - 19th February 2O2l' The Ministry of Health has embarked on phase 4 of the HePatitis B control activities in 31 districts including Kampala Metropolitan Area.- These activities are expected to run uP to October 2021 in the districts of imPlementation' The hepatitis control activities include; 1. Testing all adolescents and adults born before 2OO2 (19 years and above) 2. Testing and vaccination for those who test negative at all HCIIIs, HCIVs, General Hospitals, Regional Referral Hospitals and outreach posts. 3. Linking those who test positive for Hepatitis B for further evaluation for treatment and monitoring. This is conducted at the levels of HC IV, General Hospitals and Regional Referral Hospitals' The Ministry through National Medical Stores has availed adequate test kits and vaccines to all districts including Kampala City Courrcil' Hepatitis + Under phase 4, ttle following districts will be covered: Central I Regi6n: Kampala Metropolitan Area, Masaka, Rakai, Kyotera, Kalangala, Mpigi, Bffiambala, Gomba, Sembabule, Bukomansimbi, Lwen$o, Kalungu and Lyantonde. South Western region: Kisoro, Kanungu, Rubanda, Rukiga, Rwampara, Rukungiri, Ntungamno, Isingiro, Sheema, Mbarara, Buhweju, Mitooma, Ibanda, Kiruhura , Kazo, Kabale, Rubirizi and Bushenyi. The distribution in Kampala across the five divisions is as follows: Kawempe Division: St. Kizito Bwaise, Bwaise health clinic, Pillars clinic, Kisansa Maternity, Akugoba Maternity, Kyadondo Medical Center, Mbogo Health Clinic, Mbogo Health Clinic, Kawempe Hospital, Kiganda Maternity, Venus med center, Kisaasi COU HC, Komamboga HC, Kawempe Home care, Mariestopes, St. -

Vote: 551 Sembabule District Structure of Workplan

Local Government Workplan Vote: 551 Sembabule District Structure of Workplan Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2015/16 D: Details of Annual Workplan Activities and Expenditures for 2015/16 Page 1 Local Government Workplan Vote: 551 Sembabule District Foreword Sembabule became a District in 1997. It has two counties – Lwemiyaga with ntuusi and Lwemiyaga Sub Counties and Mawogala with Mateete Town council, Sembabule Town council and Mateete, Lwebitakuli, Mijwala and Lugusulu sub counties hence eight lower local governments. In line with the Local Government Act 1997 CAP 243, which mandates the District with the authority to plan for the Local Governments, this Budget for the Financial Year 2014-2015 has been made comprising of; The Forward, Executive Summary, and a) Revenue Peformance and Pans, b) Summary of Departmental Performance and Plans by Work plan and c) Approved Annual Work plan Outputs for 2014-2015 which have been linked to the Medium Expenditure Plan and the District Development Plan 1011-2015. and this time the District staff list. We hope this will enable elimination of ghost workers and salary payments by 28th of every month. In line with the above, the Budget is the guide for giving an insight to the district available resources and a guide to attach them to priority areas that serve the needs of the people of Sembabule District in order to improve on their standard of living with more focus to the poor, women, youth, the elderly and people with disabilities (PWDs) although not neglecting the middle income and other socioeconomic denominations by providing improver Primary health care services, Pre Primary, Primary, secondary and tertiary Education, increasing agriculture productivity by giving farm inputs and advisory services and provision of infrastructure mainly in roads and water sectors among others . -

Mother and Baby Rescue Project (Mabrp) Sector: Health Sector

MOTHER AND BABY RESCUE PROJECT (MABRP) SECTOR: HEALTH SECTOR PROJECT LOCATION: LWENGO, MASAKA AND BUKOMANSIMBI DISTRICT CONTACT PERSONS: 1. Mrs. Naluyima Proscovia 2. Mr. Isabirye Aron 3. Ms. Kwagala Juliet [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +256755858994 Tel: +256704727677 Tel: +256750399870 PROJECT TITLE: Mother And Baby Rescue Project (MABRP) PROJECT AIM: Improving maternal and newborn health PROJECT DURATION: 12 Months PROJECT FINANCE PROJECT COST: $46011.39 USD Project overview This Project is concerned with improving their maternal and newborn health in rural areas of Lwengo District, Masaka District and Bukomansimbi District by providing the necessary materials to 750 vulnerable mothers through 15 Health Centres, 5 from each district. They will be given Maama kits, basins and Mosquito nets for the pregnant mothers. This will handle seven hundred fifty (750) vulnerable pregnant mothers within the three districts for two years providing 750 maama kits, 750 mosquito nets, and 750 basins within those two years Lwengo District is bordered by Sembabule District to the north, Bukomansimbi District to the north- east, Masaka District to the east, Rakai District to the south, and Lyantonde District to the west. Lwengo is 45 kilometres (28 mi), by road, west of Masaka, the nearest large city. The coordinates of the district are: 00 24S, 31 25E. Masaka District is bordered by Bukomansimbi District to the north-west, Kalungu District to the north, Kalangala District to the east and south, Rakai District to the south-west, and Lwengo District to the west. The town of Masaka, where the district headquarters are located, is approximately 140 kilometres (87 mi), by road, south-west of Kampala on the highway to Mbarara. -

Vote:600 Bukomansimbi District Quarter1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2017/18 Vote:600 Bukomansimbi District Quarter1 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 1 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:600 Bukomansimbi District for FY 2017/18. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Accounting Officer, Bukomansimbi District Date: 27/08/2019 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2017/18 Vote:600 Bukomansimbi District Quarter1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 141,200 41,435 29% Discretionary Government Transfers 1,786,577 462,841 26% Conditional Government Transfers 9,820,059 2,546,196 26% Other Government Transfers 422,491 89,346 21% Donor Funding 535,000 91,808 17% Total Revenues shares 12,705,327 3,231,626 25% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Planning 174,866 43,333 16,453 25% 9% 38% Internal Audit 39,639 6,071 6,071 15% 15% 100% Administration 1,401,725 365,969 314,497 26% 22% 86% Finance 93,524 25,865 25,865 28% 28% 100% Statutory Bodies 351,767 71,551 60,886 20% 17% 85% Production and Marketing -

Vote:551 Sembabule District Quarter3

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:551 Sembabule District Quarter3 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 3 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:551 Sembabule District for FY 2018/19. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Accounting Officer, Sembabule District Date: 08/05/2019 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:551 Sembabule District Quarter3 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 615,345 161,677 26% Discretionary Government Transfers 3,088,581 2,409,559 78% Conditional Government Transfers 20,649,962 15,973,108 77% Other Government Transfers 1,895,403 1,002,443 53% Donor Funding 274,380 186,595 68% Total Revenues shares 26,523,671 19,733,381 74% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Planning 304,826 275,371 47,478 90% 16% 17% Internal Audit 48,268 29,534 18,929 61% 39% 64% Administration 2,314,252 1,752,979 990,864 76% 43% 57% Finance 597,914 291,280 197,152 49% 33% 68% Statutory Bodies 585,066 413,422 316,156 71% 54% 76% Production and -

State of Environment for Uganda 2004/05

STATE OF ENVIRONMENT REPORT FOR UGANDA 2004/05 The State of Environment Report for Uganda, 2004/05 Copy right @ 2004/05 National Environment Management Authority All rights reserved. National Environment Management Authority P.O Box 22255 Kampala, Uganda http://www.nemaug.org [email protected] National Environment Management Authority i The State of Environment Report for Uganda, 2004/05 Editorial committee Kitutu Kimono Mary Goretti Editor in chief M/S Ema consult Author Nimpamya Jane Technical editor Nakiguli Susan Copy editor Creative Design Grafix Design and layout National Environment Management Authority ii The State of Environment Report for Uganda, 2004/05 Review team Eliphaz Bazira Ministry of Water, Lands and Environment. Mr. Kateyo, E.M. Makerere University Institute of Environment and Natural Resources. Nakamya J. Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Amos Lugoloobi National Planning Authority. Damian Akankwasa Uganda Wildlife Authority. Silver Ssebagala Uganda Cleaner Production Centre. Fortunata Lubega Meteorology Department. Baryomu V.K.R. Meteorology Department. J.R. Okonga Water Resource Management Department. Tom Mugisa Plan for the Modernization of Agriculture. Dr. Gerald Saula M National Environment Managemnt Authority. Telly Eugene Muramira National Environment Management Authority. Badru Bwango National Environment Management Authority. Francis Ogwal National Environment Management Authority. Kitutu Mary Goretti. National Environment Management Authority. Wejuli Wilber Intern National Environment Management Authority. Mpabulungi Firipo National Environment Management Authority. Alice Ruhweza National Environment Management Authority. Kaggwa Ronald National Environment Managemnt Authority. Lwanga Margaret National Environment Management Authority. Alice Ruhweza National Environment Management Authority. Elizabeth Mutayanjulwa National Environment Management Authority. Perry Ililia Kiza National Environment Management Authority. Dr. Theresa Sengooba National Agricultural Research Organisation. -

Draft Uganda Standard

DUS 778 DRAFT UGANDA STANDARD Second Edition 2017-mm-dd Animal stock routes, check points and holding grounds — Requirements Reference number DUS 778: 2017 © UNBS 2017 DUS 778: 2017 Compliance with this standard does not, of itself confer immunity from legal obligations A Uganda Standard does not purport to include all necessary provisions of a contract. Users are responsible for its correct application © UNBS 2017 All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm, without prior written permission from UNBS. Requests for permission to reproduce this document should be addressed to The Executive Director Uganda National Bureau of Standards P.O. Box 6329 Kampala Uganda Tel: +256 414 333 250/1/2/3 Fax: +256 414 286 123 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.unbs.go.ug ii © UNBS 2017 – All rights reserved DUS 778: 2017 Contents Page Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................ iv Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... v 1 Scope ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 2 Normative references ........................................................................................................................... -

Sembabule District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi Le

Sembabule District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability profi le 2016 Acknowledgment On behalf of offi ce of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profi les. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Offi cer supported by Kirungi Raymond - Disaster Preparedness Offi cer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfi nch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred-Early Warning system Programmer. My appreciation also goes to Sembabule District Team: 1. Mr. Bimbona Simon - Chief Administrative Offi cer 2. Dr. Kawoya K Emmanuel - District Production Offi cer 3. Mr. Byaruhanga Remegeo K - Districk Agricultural Offi cer 4. Mr. Byarugaba Francis - Senior Environment Offi cer 5. Mr. Byarugaba Simon - Senior Agricultural Offi cer 6. Ms. Namuddu Amina - Information Offi cer The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. -

Planned Shutdown Web August 2020.Indd

PLANNED SHUTDOWN FOR AUGUST 2020 SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT AND ROUTINE MAINTENANCE Region Day Date Substation Planned Work District Areas & Customers To Be Affected Kampala West Saturday 1st August 2020 Mutundwe Shutdown On 132/33Kv Tx 2, To Cure Oil Leakage Nateete No Outage Expected North Eastern Monday 3rd August 2020 Lira Main Gulu 33Kv Feeder Refurbishment Works Gulu Bobi Town, Oyamu Kampala East Monday 3rd August 2020 Kawanda Umeme Pole Erection & Dressing Wandegeya Kawanda Namalere Rd, Nakyesanja, Wabitembe, Mbogo Mixed School, Marika Sweets Kampala East Monday 3rd August 2020 Kawanda Uetcl Safety Panel For Namulonge 11Kv Feeder Wandegeya No Outage Expected Shutdown On Mobile Substation Feeder 2 & 33Kv Bus Section Iii To Carry Out Cable Tororo Cement Industries, Tororo, Mbale, Busia, Bugiri, Busitema, Jinja Rd, Parts Of Kumi, Lumino, Namayengo, Tirinyi Rd, Mbale- North Eastern Tuesday 4th August 2020 Tororo Main Tororo Diversion Works In Preparation For The Installation Of 80Mva Tx3 Tororo Rd, Bubulo, Iki Iki, Nagongera, And Surroundings North Eastern Tuesday 4th August 2020 Tororo Rock Routine Maintenance Tororo Tororo Town And Sorroundings North Eastern Tuesday 4th August 2020 Tororo Rock Mv Cable Inspection, Auxilliary Mv Fusing And Jumper Repair Tororo Tororo Town And Sorroundings General Inspection Of The Transformers, Servicing Of The Tap Changers And The Station North Eastern Tuesday 4th August 2020 Tororo Rock Tororo Tororo Town And Sorroundings Auxilliary Barogole, Aler.ogur, Puranga, Rackoko, Cornerkilak, Pader, Abim, Acholibur,