1992 - Inside Talking Heads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology Fa Ct Or

Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price Origin Label Genre Release A40355 A & P Live In Munchen + Cd 2 Dvd € 24 Nld Plabo Pun 2/03/2006 A26833 A Cor Do Som Mudanca De Estacao 1 Dvd € 34 Imp Sony Mpb 13/12/2005 172081 A Perfect Circle Lost In the Bermuda Trian 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Virgi Roc 29/04/2004 204861 Aaliyah So Much More Than a Woman 1 Dvd € 19 Eu Ch.Dr Doc 17/05/2004 A81434 Aaron, Lee Live -13tr- 1 Dvd € 24 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81435 Aaron, Lee Video Collection -10tr- 1 Dvd € 22 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81128 Abba Abba 16 Hits 1 Dvd € 20 Nld Univ Pop 22/06/2006 566802 Abba Abba the Movie 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 29/09/2005 895213 Abba Definitive Collection 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 22/08/2002 824108 Abba Gold 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 21/08/2003 368245 Abba In Concert 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 25/03/2004 086478 Abba Last Video 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Univ Pop 15/07/2004 046821 Abba Movie -Ltd/2dvd- 2 Dvd € 29 Nld Polar Pop 22/09/2005 A64623 Abba Music Box Biographical Co 1 Dvd € 18 Nld Phd Doc 10/07/2006 A67742 Abba Music In Review + Book 2 Dvd € 39 Imp Crl Doc 9/12/2005 617740 Abba Super Troupers 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 14/10/2004 995307 Abbado, Claudio Claudio Abbado, Hearing T 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Tdk Cls 29/03/2005 818024 Abbado, Claudio Dances & Gypsy Tunes 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 12/12/2001 876583 Abbado, Claudio In Rehearsal 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 23/06/2002 903184 Abbado, Claudio Silence That Follows the 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 5/09/2002 A92385 Abbott & Costello Collection 28 Dvd € 163 Eu Univ Com 28/08/2006 470708 Abc 20th Century Masters -

We Need Water!

CONCEPTS OF COMPREHENSION: CAUSE AND EFFECT 2n d GRADE UNIT Reading Passage We Need Water! Every living thing needs water to live. People need clean, fresh water for drinking, washing, and having fun. How do you use water? Watch the Water Cycle Water is found nearly everywhere. It is in the ground we walk on and in the air we breathe. Water moves from land to sky and back again. That journey is called the water cycle. Did you ever wonder where that glass of water comes from? Take a look! USGS The water cycle. 1 Text: Copyright © 2005 Weekly Reader Corporation. All rights reserved. Weekly Reader is a registered trademark of Weekly Reader Corporation. Used by permission. From Weekly Reader 2, Student Edition, 4/1/05. © 2010 Urban Education Exchange. All rights reserved. CONCEPTS OF COMPREHENSION: CAUSE AND EFFECT 2n d GRADE UNIT Reading Passage 1. The sun warms the water in rivers, lakes, and oceans. Soon the warm water changes into a gas. That change is called evaporation1. The gas floats up and forms clouds in the sky. 2. The gas in clouds cools. Soon the cool gas turns back into water. That change is called condensation2. 3. Water falls from the clouds to Earth as raindrops or snowflakes. That process is called precipitation3. 4. Rain soaks into the ground. The water flows back into the rivers, lakes, and oceans. That process is called collection4. Soon the water cycle starts all over again. Protect Water! Photos.com Turn off the faucet while brushing your Here are some tips you can follow to teeth. -

Tom Tom Club's Christmas Stocking Stuffers

2002 - Tom Tom Club's Christmas Stocking Stuffers Interview with ex-Talking Head and Tom Tom Club's Chris FrantzDec. 15, 2002 Just in time for the holiday season ex-Talking Heads turned Tom Tom Club alumni Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth are filling their fan's Christmas stockings with two new downloadable holiday chestnuts from their website, http://www.tomtomclub.net . Both Chris and Tina, along with David Byrne and Jerry Harrison were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame earlier this year, and while their work with the Talking Heads is what they may be best known for, the wedded couple have also, for the last twenty years, been busy making their own brand of uninhibited party music with their band Tom Tom Club. Surprisingly, its their own music with the Tom Tom Club, and not the Talking Heads, that has permeated itself into so many different styles of music over the past two decades, as their 1983 hit "Genius of Love" is the most sampled song of all time, with artists such as 2PAC, Ziggy Marley, the X-ecutioners and Mariah Carey either sampling bits or recreating the entire song. Livewire's Tony Bonyata caught up with Chris to talk about the Heads, the impact of Tom Tom Club, as well as their delightful new stocking stuffers. Livewire: I understand that you're giving your fans a couple of early Christmas presents on your web site this season. Chris: Yeah, we are. The first one, which is already posted on the homepage of our site, tomtomclub.com, is a very traditional, beautiful and kind of chilled-out French carol called "Il Est Ne," which is French for "He Is Born." It's very traditional, and I'm sure you'll recognize it when you hear the melody. -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Gommittee Recommends Ballpark Site Phi Psi Changes Theme Party Name

THE CHRONICLE THURSDAY, OCTOBER 19, 1989 DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL. 85, NO. 38 Gommittee recommends ballpark site By LENOREYARGER the positive aspects of the siting, A four member committee . [the University Ford site] presented city and county repre seemed to be best," Gulley said. sentatives with a recommenda The recommended site is lo tion Wednesday night to locate cated near the American Tobacco Durham's proposed baseball sta land currently being renovated dium at the downtown Univer and redeveloped by the Adaron sity Ford site. Group, the University and the The committee also recom Edgar Bronfman family. mended that the county com The committee considered two pletely fund the stadium, leaving additional sites in addition to the the financing of infrastructure University Ford location. These needs to the city. other two options were for con Durham Mayor Wib Gulley, structing the new ballpark at the Briggs Avenue site and renovat City Manager Orville Powell, CHAD HOOD/THE CHRONICLE County Manager Jack Bond and ing or building a new facility at Chair of the Board of Commis William Bell and Wib Gulley the Durham Athletic Park sioners William Bell presented (DAP), current home of the Dur the University Ford dealership working on their recommenda ham Bulls. site as their first choice for the tion ever since the joint city/ "For all of us, we continue to be location of an 8,000 seat ballpark county council appointed them to flexible and open-minded about to the Durham City Council and the task at their last meeting in it [the site selection]," Gulley Durham County Board of Com June. -

You Can Choose to Be Happy

You Can Choose To Be Happy: “Rise Above” Anxiety, Anger, and Depression with Research Evidence Tom G. Stevens PhD Wheeler-Sutton Publishing Co. YOU CAN CHOOSE TO BE HAPPY: “Rise Above” Anxiety, Anger, and Depression With Research Evidence Tom G. Stevens PhD Wheeler-Sutton Publishing Co. Palm Desert, California 92260 Revised (Second) Edition, 2010 First Edition, 1998; Printings, 2000, 2002. Copyright © 2010 by Tom G. Stevens PhD. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews; or except as provided by U. S. copyright law. For more information address Wheeler-Sutton Publishing Co. The cases mentioned herein are real, but key details were changed to protect identity. This book provides general information about complex issues and is not a substitute for professional help. Anyone needing help for serious problems should see a qualified professional. Printed on acid-free paper. Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stevens, Tom G., Ph.D. 1942- You can choose to be happy: rise above anxiety, anger, and depression./ Tom G. Stevens Ph.D. –2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9653377-2-4 1. Happiness. 2. Self-actualization (Psychology) I. Title. BF575.H27 S84 2010 (pbk.) 158-dc22 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009943621 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: ..................................................................................................................... -

"Erase Me": Gary Numan's 1978-80 Recordings

Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 4 June 2021 "Erase Me": Gary Numan's 1978-80 Recordings John Bruni [email protected], [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ought Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Disability Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bruni, John (2021) ""Erase Me": Gary Numan's 1978-80 Recordings," Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ought/vol2/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Erase Me”: Gary Numan’s 1978-80 Recordings John Bruni ary Numan, almost any way you look at him, makes for an unlikely rock star. He simply never fits the archetype: his best album, both Gin terms of artistic and commercial success, The Pleasure Principle (1979), has no guitars on it; his career was brief; and he retired at his peak. Therefore, he has received little critical attention; the only book-length analysis of his work is a slim volume from Paul Sutton (2018), who strains to fit him somehow into the rock canon. With few signposts at hand—and his own open refusal to be a star—writing about Numan is admittedly a challenge. In fact, Numan is a good test case for questioning the traditional belief in the authenticity of individual artistic genius. -

Scarlet and Cream to Erderiam Troops UNL's Scarlet and Cream Singers Will Spend Part of Their Summer Entertaining U.S

18, 1934 Pano 10 Daily Nebraskan Wednesday, April Aits i !! II II ll Scarlet and Cream to erderiam troops UNL's Scarlet and Cream Singers will spend part of their summer entertaining U.S. troops "over there" or "up there " to be more accurate. Eight members of the 14 member troupe will per- form for military personnel stationed in St. Johns, : Newfoundland, Thulie, Greenland and Sondistrom, x Greenland. Barb Wright, director ofstudent programs for the university Alumni Association said the armed for- ces professional entertainment department, which is the would mem- organizing tour, allow only eight S e bers to visit. 1 v., X' J "We narrowed the group down solely on seniori- 4. r'l ty," she said. There are 14 in Scarlet and f normally singers L Cream, in addition to a four-piec- e band and three full-tim- e technicians. Since all the people making the trip are vocalists, the band will pre-tap- e some music to accompany the singing, she said. 1 The eight making the trip are Julie Beranek. a t - sophomore from Lincoln; Ellen Kollars, a sopho- more from Arlington; Julie Chadwick, a junior from Lincoln; Anna Baker, a junior from Lincoln; Mark Thornburg, a sophomore from Beatrice; Rod Weber, a freshman from Blair; John Kahle, a freshman from Kearney, and Rob Reeder, a sophomore from Lin- coln. Wright said this is the first time in the group's 1 history they have been asked to perform for the military. However, it is not the first time the troupe has performed overseas. -

Fear of Music

Fear of Music ----------- I Zimbra ----------- GADJI BERI BIMBA CLANDRIDI LAULI LONNI CADORI GADJAM A BIM BERI GLASSALA GLANDRIDE E GLASSALA TUFFM I ZIMBRA BIM BLASSA GALASSASA ZIMBRABIM BLASSA GLALLASSASA ZIMBRABIM A BIM BERI GLASSALA GRANDRID E GLASSALA TUFFM I ZIMBRA GADJI BERI BIMBA GLANDRIDI LAULI LONNI CADORA GADJAM A BIM BERI GLASSASA GLANDRID E GLASSALA TUFFM I ZIMBRA ------- Mind ------- Time won't change you Money won't change you I haven't got the faintest idea Everything seems to be up in the air at this time I need something you change your mind 1 / 12 Fear of Music Drugs won't change you Religion won't change you Science won't change you Looks like I can't change you I try to talk to you, to make things clear but you're not even listening to me... And it comes directly from my heart to you... I need something to change your mind. ------- Paper ------- Hold the paper up to the light (some rays pass right through) Expose yourself out there for a minute (some rays pass right through) Take a little rest when the rays pass through Take a little time off when the rays pass through Go ahead and mis it up...Go ahead and tie it up In a long distance telephone call Hold on to that paper Hold on to that paper Hold on becuase it's been taken care of Hold on to that paper 2 / 12 Fear of Music See if you can fit it on the paper See if you can get it on the paper See if you can fit it on the paper See if you can get it on the paper Had a love affair but it was only paper (some rays they pass right through) Had a lot of fun, could have been -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

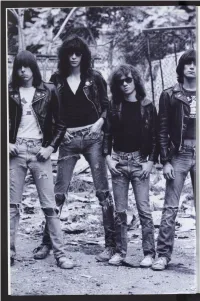

ADAM and the ANTS Adam and the Ants Were Formed in 1977 in London, England

ADAM AND THE ANTS Adam and the Ants were formed in 1977 in London, England. They existed in two incarnations. One of which lasted from 1977 until 1982 known as The Ants. This was considered their Punk era. The second incarnation known as Adam and the Ants also featured Adam Ant on vocals, but the rest of the band changed quite frequently. This would mark their shift to new wave/post-punk. They would release ten studio albums and twenty-five singles. Their hits include Stand and Deliver, Antmusic, Antrap, Prince Charming, and Kings of the Wild Frontier. A large part of their identity was the uniform Adam Ant wore on stage that consisted of blue and gold material as well as his sophisticated and dramatic stage presence. Click the band name above. ECHO AND THE BUNNYMEN Formed in Liverpool, England in 1978 post-punk/new wave band Echo and the Bunnymen consisted of Ian McCulloch (vocals, guitar), Will Sergeant (guitar), Les Pattinson (bass), and Pete de Freitas (drums). They produced thirteen studio albums and thirty singles. Their debut album Crocodiles would make it to the top twenty list in the UK. Some of their hits include Killing Moon, Bring on the Dancing Horses, The Cutter, Rescue, Back of Love, and Lips Like Sugar. A very large part of their identity was silohuettes. Their music videos and album covers often included silohuettes of the band. They also have somewhat dark undertones to their music that are conveyed through the design. Click the band name above. THE CLASH Formed in London, England in 1976, The Clash were a punk rock group consisting of Joe Strummer (vocals, guitar), Mick Jones (vocals, guitar), Paul Simonon (bass), and Topper Headon (drums). -

Talking Heads -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

Talking Heads / David Byrne / A+ A B+ B C D updated: 09/06/2005 Tom Tom Club / Jerry Harrison / ARTISTS = Artists I´m always looking to trade for new shows not on my list :-) The Heads DVD+R for trade: (I´ll trade 1 DVD+R for 2 CDRs if you haven´t a DVD I´m interested and you still would like to tarde for a DVD+R before contact me here are the simple rules of trading policy: - No trading of official released CD´s, only bootleg recordings, - Please use decent blanks. (TDK, Memorex), - I do not sell any bootleg or copies of them from my list. Do not ask!! - I send CDRs only, no tapes, Trading only !!! ;-), - I don't do blanks & postage or 2 for 1's; fair trading only (CD for a CD or CD for a tape), I trade 1 DVD+R for 2 CDRs if you haven´t a DVD I´m - Pack well, ship airmail interested - CD's should be burned DAO, without 2 seconds gaps between the - Don´t send Jewel Cases, use plastic or paper pockets instead, I´ll do the same tracks, - For set lists or quality please ask, - No writing on the disks please - Please include a set list or any venue info, I´l do the same, - Keep contact open during trade to work out a trade please contact me: [email protected] TERRY ALLEN Stubbs, Austin, TX 1999/03/21 Audience Recording (feat. David Byrne) CD Amarillo Highway / Wilderness Of This World / New Delhi Freight Train / Cortez Sail / Buck Naked (w/ David Byrne) / Bloodlines I / Gimme A Ride To Heaven Boy DAVID BYRNE In The Pink Special --/--/-- TV-broadcast / documentary DVD+R Interviews & music excerpts TV-Show Appearances 1990 - 2004 TV-broadcasts (quality differs on each part) DVD+R I.