Additional Records of Lazuli Bunting (Passerina Amoena) and First Records of Several Wild-Caught Exotic Birds for Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentation Outline

Nepal - nature, biodiversity & conservation Presentation outline • Nature: physiographic & climatic cond. & biodiversity • Bird diversity (rep. 38 families outof 69) • Threat status • Conservation initiatives Tej Basnet E-mail: [email protected] 2 Where is Nepal ........ Himalaya N Source: Hagen, T. 1998 Total area: 147181 SQ KM (0.1% land of earth) It contains the highest mountains in the world, The majestic Himalaya range Small, landlocked contains Eight of the world’s highest mountains, culminating in Mt. Everest. Population: 27,800,000 (approx) Agriculture dependent : 66% 3 4 1 Mt. Everest A 3600 footage at Lobuche (>5000m asl), from Everest region 5 6 Climate & physiographic general pattern in Nepal Physiographic zones with corresponding bioclimatic zones and sub-zones Cold Paleoarctic Pan Zone Physiographic Corresponding Bioclimatic zones & zones (LRMP 1986) sub-zones (Dobremez, 1972) High Himal zones sub-zones (altitudinal range) High Mountain Mid Hill High Himal Nival (above 5000m) Siwaliks Tarai Alpine Upper (from 4500 to 5000m) Lower (from 4000 to 4500m) High Mountain Sub-alpine Upper (from 3500 to 4000m) Lower (from 3000 to 3500m) Temperate Upper (from 2500 to 3000m Lower (from 2000 to 2500m) Mid Hill Sub-tropical Upper (from 1500 to 2000m) Lower (from 1000 to 1500m) Paleotropic Pan Zone Hot Altitude 60m – 8848m asl. Siwalik Tropical Upper (from 500 to 1000m) Terai Lower (below 500m) 7 8 Spectacular view from south to north Photo: R. Suwal 2 ”Walking through magnificent forests of Nepal’s contribution of Biodiversity in World‘s Total oak and rhododendrons beneath the towering white summits, one can Plant Species Animal Species understand why some claim this to be Group World Nepal Group World Nepal the most beautiful place on the planet”. -

![DRR-Team Mission Report [Cuba – Havana Province and City]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5802/drr-team-mission-report-cuba-havana-province-and-city-75802.webp)

DRR-Team Mission Report [Cuba – Havana Province and City]

DRR-Team Mission Report [Cuba – Havana Province and City] July 17-23, 2018 1. DRR-TEAM MISSION REPORT CUBA October 2018 1 Effect of Hurricane driven wave action on the Malecón (sea wall) of Havana 1. DRR-TEAM MISSION REPORT CUBA October 2018 2 DRR-TEAM [CUBA] Document title Mission Report Status Final Date 04 October 2018 Project name DRR- water related risks in the “La Habana Province” of Cuba Reference DRR218CU Drafted by Marinus Pool, Joana van Nieuwkoop, Arend Jan van de Kerk Checked by Hugo de Vries, RVO/ Bob Oeloff, Babette Graber, I&W/ Cor Schipper, RWS/ NL Embassy Cuba/ DRR- coordinator RVO/ Henk Ovink Date/initials check 11 October 2018 Approved by Mr. Lisa Hartog 1. DRR-TEAM MISSION REPORT CUBA October 2018 3 SUMMARY Again, just over a year ago, after hurricane Wilma hit the Cuban coast severely in 2005, hurricane Irma swept over the northern coast of Cuba resulting in heavy damages and inundations of coastal settlements. Only two months later, on the occasion of the signing of a Letter of Intent (November 2017) between The Netherlands and Cuba, which reflects intended cooperation in the field of reduction of costal vulnerability to Climate Change, support to integrated water management and transfer of associated technologies. Soon after, Cuba’s Deputy Minister of Science, Technology and the Environment (CITMA), José Fidel Santana Nuñez, requested in his letter of March 29, 2018, to the Dutch Deputy Minister for Foreign Economic Relations, for Dutch assistance in the field of joint research on coastal flood management with emphasis on the design of infrastructure and environmental engineering in densely populated areas (in this case La Habana) all on the basis of modeling of wave energy dissipation and reduction of coastal vulnerability. -

Printable PDF Format

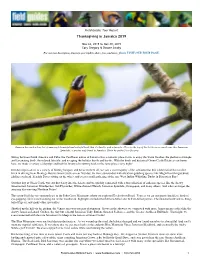

Field Guides Tour Report Thanksgiving in Jamaica 2019 Nov 24, 2019 to Nov 30, 2019 Cory Gregory & Dwane Swaby For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Jamaica has such a long list of amazingly beautiful and colorful birds that it's hard to pick a favorite. Close to the top of the list however surely was this Jamaican Spindalis, a species only found in Jamaica. Photo by guide Cory Gregory. Sitting between South America and Cuba, the Caribbean nation of Jamaica was a fantastic place for us to enjoy the warm weather, the plethora of unique and fascinating birds, the relaxed lifestyle, and escaping the holiday hustle and bustle. With the birdy and historical Green Castle Estate as our home base, we made a variety of daytrips and had the luxury of returning back to the same place every night! Our day trips took us to a variety of birding hotspots and between them all, we saw a vast majority of the avifauna that this island nation has to offer. Even in driving from Montego Bay to Green Castle on our first day, we were surrounded with attention-grabbing species like Magnificent Frigatebirds gliding overhead, Zenaida Doves sitting on the wires, and even a small gathering of the rare West Indian Whistling-Ducks in Discovery Bay! Our first day at Green Castle was our first foray into the forests and we quickly connected with a fun collection of endemic species like the showy Streamertail, Jamaican Woodpecker, Sad Flycatcher, White-chinned Thrush, Jamaican Spindalis, Orangequit, and many others. -

Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer Domesticus

46 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2005, 22, 46--47 Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer domesticus NEIL SHELLEY 16 Birdrock Avenue, Mount Martha, Victoria 3934 (Email: [email protected]) Summary This note describes an incidental observation of House Sparrows Passer domesticus foraging for insects trapped within the engine bay of motor vehicles in south-eastern Australia. Introduction The House Sparrow Passer domesticus is commensal with man and its global range has increased significantly recently, closely following human settlement on most continents and many islands (Long 1981, Cramp 1994). It is native to Eurasia and northern Africa (Cramp 1994) and was introduced to Australia in the mid 19th century (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999). It is now common in cities and towns throughout eastern Australia (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999, Barrett et al. 2003), particularly in association with human habitation (Schodde & Tidemann 1997), but is decreasing nationally (Barrett et al. 2003). Observation On 13 January 2003 at c. 1745 h Eastern Summer Time, a small group of House Sparrows was observed foraging in the street outside a restaurant in Port Fairy, on the south-western coast of Victoria (38°23' S, 142°14' E). Several motor vehicles were angle-parked in the street, nose to the kerb, adjacent to the restaurant. The restaurant had a few tables and chairs on the footpath for outside dining. The Sparrows appeared to be foraging only for food scraps, when one of them entered the front of a parked vehicle and emerged shortly after with an insect, which it then consumed. -

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology

THE J OURNAL OF CARIBBEAN ORNITHOLOGY SOCIETY FOR THE C ONSERVATION AND S TUDY OF C ARIBBEAN B IRDS S OCIEDAD PARA LA C ONSERVACIÓN Y E STUDIO DE LAS A VES C ARIBEÑAS ASSOCIATION POUR LA C ONSERVATION ET L’ E TUDE DES O ISEAUX DE LA C ARAÏBE 2005 Vol. 18, No. 1 (ISSN 1527-7151) Formerly EL P ITIRRE CONTENTS RECUPERACIÓN DE A VES M IGRATORIAS N EÁRTICAS DEL O RDEN A NSERIFORMES EN C UBA . Pedro Blanco y Bárbara Sánchez ………………....................................................................................................................................................... 1 INVENTARIO DE LA A VIFAUNA DE T OPES DE C OLLANTES , S ANCTI S PÍRITUS , C UBA . Bárbara Sánchez ……..................... 7 NUEVO R EGISTRO Y C OMENTARIOS A DICIONALES S OBRE LA A VOCETA ( RECURVIROSTRA AMERICANA ) EN C UBA . Omar Labrada, Pedro Blanco, Elizabet S. Delgado, y Jarreton P. Rivero............................................................................... 13 AVES DE C AYO C ARENAS , C IÉNAGA DE B IRAMA , C UBA . Omar Labrada y Gabriel Cisneros ……………........................ 16 FORAGING B EHAVIOR OF T WO T YRANT F LYCATCHERS IN T RINIDAD : THE G REAT K ISKADEE ( PITANGUS SULPHURATUS ) AND T ROPICAL K INGBIRD ( TYRANNUS MELANCHOLICUS ). Nadira Mathura, Shawn O´Garro, Diane Thompson, Floyd E. Hayes, and Urmila S. Nandy........................................................................................................................................ 18 APPARENT N ESTING OF S OUTHERN L APWING ON A RUBA . Steven G. Mlodinow................................................................ -

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material Species Richness and Abundance of Birds in and Around Nimule National Park, South Sudan Gift Sarafadin Simon1*, Elijah Oyoo Okoth2 Table S1Checklist of birds recorded during this study in the Nimule National Park. S/No. Common Name Scientific Name 1 Abyssinian Roller Coracias abyssinica 2 African Blue Flycatcher Elminia longicauda 3 African Cuckoo-Hawk Aviceda cuculoides 4 African Darter Anhinga rufa 5 African Fish-Eagle Haliaeetus vocifer 6 African Grey Hornbill Tockus nasutus 7 African Hoopoe Upupa epops 8 African Jacana Actophilornis africanus 9 African Mourning Dove Streptopelia decipiens 10 African Palm Swift Cypsiurus parvus 11 African Paradise-Flycatcher Terpsiphone viridis 12 Pied Crow Corvus albus 13 African Pied Hornbill Tockus fasciatus 14 Pied Kingfisher Ceryle rudis 15 African Pied Wagtail Motacilla aguimp 16 African Pipit Anthus cinnamomeus 17 African Sacred Ibis Threskiornis aethiopicus 18 African Silverbill Lonchura cantans 19 African Skimmer Rynchops flavirostris 20 Alpine Swift Tachymarptis melba 21 Ashy Starling Lamprotornis unicolor 22 Bare-Face Go- Away Bird Corythaixoides personatus 23 Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica 24 Beautiful Sunbird Cinnyris pulchella 25 Black And White Flycatcher Bias musicus 26 Black-Billed Turaco Tauraco schuettii 27 Black-Billed Wood Dove Turtur abyssinicus 28 Black Crake Amaurornis flavirostra 29 Black Crowned Crane Balearica pavonina 30 Black Cuckoo Cuculus clamosus 31 Black Cuckooshrike Campephaga flava 32 Black Dwarf Hornbill Tockus hartlaubi 33 Northern Red-Billed -

An Annotated List of Birds Wintering in the Lhasa River Watershed and Yamzho Yumco, Tibet Autonomous Region, China

FORKTAIL 23 (2007): 1–11 An annotated list of birds wintering in the Lhasa river watershed and Yamzho Yumco, Tibet Autonomous Region, China AARON LANG, MARY ANNE BISHOP and ALEC LE SUEUR The occurrence and distribution of birds in the Lhasa river watershed of Tibet Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China, is not well documented. Here we report on recent observations of birds made during the winter season (November–March). Combining these observations with earlier records shows that at least 115 species occur in the Lhasa river watershed and adjacent Yamzho Yumco lake during the winter. Of these, at least 88 species appear to occur regularly and 29 species are represented by only a few observations. We recorded 18 species not previously noted during winter. Three species noted from Lhasa in the 1940s, Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata, Solitary Snipe Gallinago solitaria and Red-rumped Swallow Hirundo daurica, were not observed during our study. Black-necked Crane Grus nigricollis (Vulnerable) and Bar-headed Goose Anser indicus are among the more visible species in the agricultural habitats which dominate the valley floors. There is still a great deal to be learned about the winter birds of the region, as evidenced by the number of apparently new records from the last 15 years. INTRODUCTION limited from the late 1940s to the early 1980s. By the late 1980s the first joint ventures with foreign companies were The Lhasa river watershed in Tibet Autonomous Region, initiated and some of the first foreign non-governmental People’s Republic of China, is an important wintering organisations were allowed into Tibet, enabling our own area for a number of migratory and resident bird species. -

A Comprehensive Multilocus Assessment of Sparrow (Aves: Passerellidae) Relationships ⇑ John Klicka A, , F

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 77 (2014) 177–182 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Short Communication A comprehensive multilocus assessment of sparrow (Aves: Passerellidae) relationships ⇑ John Klicka a, , F. Keith Barker b,c, Kevin J. Burns d, Scott M. Lanyon b, Irby J. Lovette e, Jaime A. Chaves f,g, Robert W. Bryson Jr. a a Department of Biology and Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, Box 353010, Seattle, WA 98195-3010, USA b Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior, University of Minnesota, 100 Ecology Building, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA c Bell Museum of Natural History, University of Minnesota, 100 Ecology Building, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA d Department of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182, USA e Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14950, USA f Department of Biology, University of Miami, 1301 Memorial Drive, Coral Gables, FL 33146, USA g Universidad San Francisco de Quito, USFQ, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, y Extensión Galápagos, Campus Cumbayá, Casilla Postal 17-1200-841, Quito, Ecuador article info abstract Article history: The New World sparrows (Emberizidae) are among the best known of songbird groups and have long- Received 6 November 2013 been recognized as one of the prominent components of the New World nine-primaried oscine assem- Revised 16 April 2014 blage. Despite receiving much attention from taxonomists over the years, and only recently using molec- Accepted 21 April 2014 ular methods, was a ‘‘core’’ sparrow clade established allowing the reconstruction of a phylogenetic Available online 30 April 2014 hypothesis that includes the full sampling of sparrow species diversity. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Title Template

AMPHIBIANS OF CUBA: CHECKLIST AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTIONS Vilma Rivalta González, Lourdes Rodríguez Schettino, Carlos A. Mancina, & Manuel Iturriaga Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología y Medio Ambiente SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 145 2014 . SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The first number of the SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE series appeared in 1968. SHIS number 1 was a list of herpetological publications arising from within or through the Smithsonian Institution and its collections entity, the United States National Museum (USNM). The latter exists now as little more than the occasional title for the registration activities of the National Museum of Natural History. No. 1 was prepared and printed by J. A. Peters, then Curator-in-Charge of the Division of Amphibians & Reptiles. The availability of a NASA translation service and assorted indices encouraged him to continue the series and distribute these items on an irregular schedule. The series continues under that tradition. Specifically, the SHIS series distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, and unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such an item, please contact George Zug [zugg @ si.edu] for its consideration for distribution through the SHIS series. Our increasingly digital world is changing the manner of our access to research literature and that is now true for SHIS publications. They are distributed now as pdf documents through two Smithsonian outlets: BIODIVERSITY HERITAGE LIBRARY. -

4911651E2.Pdf

Change in Cuba: How Citizens View Their Country‘s Future Freedom House September 15, 2008 Civil Society Analysis Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 1 Research Findings ........................................................................................................................... 3 Daily Concerns ............................................................................................................................ 3 Restrictions on Society ................................................................................................................ 7 Debate Critico ............................................................................................................................. 8 Cuba‘s New Leadership .............................................................................................................. 9 Structural Changes .................................................................................................................... 10 Timeline .................................................................................................................................... 11 State Institutions -

Assessment and Conservation of Threatened Bird Species at Laojunshan, Sichuan, China

CLP Report Assessment and conservation of threatened bird species at Laojunshan, Sichuan, China Submitted by Jie Wang Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, P.R.China E-mail:[email protected] To Conservation Leadership Programme, UK Contents 1. Summary 2. Study area 3. Avian fauna and conservation status of threatened bird species 4. Habitat analysis 5. Ecological assessment and community education 6. Outputs 7. Main references 8. Acknowledgements 1. Summary Laojunshan Nature Reserve is located at Yibin city, Sichuan province, south China. It belongs to eastern part of Liangshan mountains and is among the twenty-five hotspots of global biodiversity conservation. The local virgin alpine subtropical deciduous forests are abundant, which are actually rare at the same latitudes and harbor a tremendous diversity of plant and animal species. It is listed as a Global 200 ecoregion (WWF), an Important Bird Area (No. CN205), and an Endemic Bird Area (No. D14) (Stattersfield, et al . 1998). However, as a nature reserve newly built in 1999, it is only county-level and has no financial support from the central government. Especially, it is quite lack of scientific research, for example, the avifauna still remains unexplored except for some observations from bird watchers. Furthermore, the local community is extremely poor and facing modern development pressures, unmanaged human activities might seriously disturb the local ecosystem. We conducted our project from April to June 2007, funded by Conservation Leadership Programme. Two fieldwork strategies were used: “En bloc-Assessment” to produce an avifauna census and ecological assessments; "Special Survey" to assess the conservation status of some threatened endemic bird species.