Of Boom and Bust 243

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scoping Report: Grand Staircase-Escalante National

CONTENTS 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 2 Scoping Process ....................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Purpose of Scoping ........................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Scoping Outreach .............................................................................................................................. 3 2.2.1 Publication of the Notice of Intent ....................................................................................... 3 2.2.2 Other Outreach Methods ....................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Opportunities for Public Comment ................................................................................................ 3 2.4 Public Scoping Meetings .................................................................................................................. 4 2.5 Cooperating Agency Involvement ................................................................................................... 4 2.6 National Historic Preservation Act and Tribal Consultation ....................................................... 5 3 Submission Processing and Comment Coding .................................................................................... 5 -

A Preliminary Assessment of Archaeological Resources Within the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah

A PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCES WITHIN THE GRAND STAIRCASE-ESCALANTE NATIONAL MONUMENT, UTAH by David B. Madsen Common rock art elements of the Fremont and Anasazi on the Colorado Plateau and the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. ,I!! CIRCULAR 95 . 1997 I~\' UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ." if;~~ 6EPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ISBN 1-55791-605-5 STATE OF UTAH Michael O. Leavitt, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Ted Stewart, Executive Director UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY M. Lee Allison~ Director UGS Board Member Representing Russell C. Babcock, Jr. (chairman) .................................................................................................. Mineral Industry D. Cary Smith ................................................................................................................................... Mineral Industry Richard R. Kennedy ....................................................................................................................... Civil Engineering E.H. Deedee O'Brien ......................................................................................................................... Public-at-Large C. William Berge .............................................................................................................................. Mineral Industry Jerry Golden ..................................................................................................................................... Mineral Industry Milton E. Wadsworth ............................................................................................... -

5. Location of Legal Description

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_____________. 1. Name historic Ensign-Smith House and/or common Silas Smith House 2. Location street & number 96 Main not for publication city, town Paragonah vicinity of state Utah code 049 county Iron code 021 3. Classification Category Ownership States Present Use _ ^district _kloccupied agriculture museum _ _ building(s) _i^lprivate unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational Lf^private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process V yes: restricted government scientific _ L being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation n no military other: 4. Owner of Property name R. J. Reynolds street & number Box 384 city, town Palm Springs vicinity of state CA 92263 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Iron County Courthouse street & number city, town Parowan state Utah 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Utah Historic Sites Survey/ title Iron County Survey______ has this property been determined elegible? yes no date SP rin 9 1981 federal X state county local depository for survey records Utah State Historical Society city, town Lake Ci state Utah 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent ^,__ deteriorated .. unaltered X original site _A_ goodC* » -- l<-_ ruins ^ altered __ moved date __ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The En sign -Smith house in Paragonah is a long (the front section measures about 50' x 17') 1-1/2 story adobe house. -

Grand Staircase-Escalante National‘ Monument Annual Manager’S Report—Fiscal Year 2016 Table of Contents

Utah Grand Staircase-Escalante National‘ Monument Annual Manager’s Report—Fiscal Year 2016 Table of Contents Grand Staircase-Escalante Profile ..................................................................................... 2 Planning and NEPA ............................................................................................................. 6 2016 Projects and Accomplishments ................................................................................ 9 Science .............................................................................................................................. 35 Resources, Objects, Values, and Stressors ..................................................................... 57 Summary of Performance Measure ................................................................................. 84 Manager’s Letter ............................................................................................................... 88 1 1 Grand Staircase-Escalante Profile Designating Authority Designating Authority: Presidential Proclamation 6920 Date of Designation: September 18, 1996 Acreage Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (GSENM) spans nearly 1.9 million acres of America’s public lands. Managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), GSENM is part of the National Conservation Lands. Reporting directly to the BLM Utah State Office, the Monument Manager oversees public lands which contain some of America’s most scientifically exciting and visually stunning landscapes. The Monument boundary encompasses -

River Flowing from the Sunrise: an Environmental History of the Lower San Juan

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 River Flowing from the Sunrise: An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan James M. Aton Robert S. McPherson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Recommended Citation Aton, James M. and McPherson, Robert S., "River Flowing from the Sunrise: An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan" (2000). All USU Press Publications. 128. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/128 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. River Flowing from the Sunrise An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan A. R. Raplee’s camp on the San Juan in 1893 and 1894. (Charles Goodman photo, Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library, University of Utah) River Flowing from the Sunrise An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan James M. Aton Robert S. McPherson Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press all rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 Manfactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper 654321 000102030405 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aton, James M., 1949– River flowing from the sunrise : an environmental history of the lower San Juan / James M. Aton, Robert S. McPherson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87421-404-1 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-87421-403-3 (pbk. -

2019-20 Arizona Hunting Regulations

ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT 2019-20 Arizona Hunting Regulations This is the last draw in which paper applications will be accepted. This booklet includes annual regulations for statewide hunting of deer, fall turkey, fall javelina, bighorn sheep, fall bison, fall bear, mountain lion, small game and other huntable wildlife.* PAPER hunt permit application deadline is Tuesday, May 14, 2019 at 7:00 p.m. Arizona time. ONLINE hunt permit application deadline is Tuesday, June 11, 2019 at 11:59 p.m. Arizona time. You may purchase Arizona hunting licenses and apply for the draw online. To report wildlife violations, call: 800-352-0700. * Two other annual hunt draw information booklets are published for spring big game hunts and elk and pronghorn antelope hunts covering season dates, open areas, permits and drawing/application information. Unforgettable Adventures. Feel-Good Savings. Heed the call of adventure with great insurance coverage. 15 minutes could save you 15% or more on motorcycle insurance. geico.com | 1-800-442-9253 | Local Office Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Motorcycle and ATV coverages are underwritten by GEICO Indemnity Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2019 GEICO AdPages2019.indd 7 4/18/2019 2:05:06 PM 2019-20 Arizona Hunting Regulations 1 AdPages2019.indd 6 4/18/2019 2:52:51 PM 2019 RANGER CREW® XP 1000 EPS POLARIS PURSUIT® CAMO STARTING US MSRP $17,699 2019 GENERAL™ 1000 EPS HUNTERS ED. -

Canyons of the Escalante Information and Hiking Guide

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glen Canyon National Recreation Area Rainbow Bridge National Monument Canyons of the Escalante Information and Hiking Guide Everett Ruess linocuts taken from Everett Ruess: A Vagabond for Beauty by W. L. Rusho, published by Gibbs-Smith. Used by permission. These days away from the city have been the happiest of my life...It has all been a beautiful dream, sometimes tranquil, sometimes fantastic, and with enough pain and tragedy to make the delights possible by contrast. - Everett Ruess from a letter to his friend Bill soon after beginning his journey. The Escalante Canyons include some of the most remote, wild, and beautiful country in the Southwest. The Escalante, the last river in the continental United States to be named, meanders slowly between towering canyon walls. Its tributaries, also deeply entrenched in sandstone, contain arches, natural bridges, and waterfalls. The area is reminiscent of Glen Canyon before Lake Powell and offers some of the finest opportunities for desert hiking on the Colorado Plateau. National Park Service 1 BASIC INFORMATION ADMINISTRATION AND INFORMATION Public lands in the Escalante area are administered by the National Park Service (Glen Canyon National Recreation Area), the Bureau of Land Management (Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument), and the U.S. Forest Service (Dixie National Forest). Information ABOUT THE ESCALANTE AREA: Escalante Interagency Visitor Information Center, PO Box 511 Escalante, UT 84726 435-826-5499 EMERGENCIES National Park Service: Escalante Ranger Station 435-826-4315 24 Hour Dispatch 800-582-4351 Bureau of Land Management: Escalante Office 435-826-4291 U.S. -

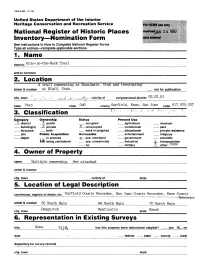

Nomination Form See Instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries—Complete Applicable Sections______1

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections____________________ 1. Name____________________ historic Hole-in-the-Rock Trail and/or common___________________________________________ 2. Location_____ A trail commencing at Escalante, Utah and terminating street & number at Bluff, Utah. not for publication city, town vicinity of congressional district ^, CL, 01 state Utah code 049 county Garfield, Kane, San Juan code 017,025,037 3. Classification c *':.< f .'-;-. &"/•...,-*- rt>"-* ? £^ V""'"' •'"''. Category Ownership Status Present Use X district X public occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private X unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific VIK being considered - yes: unrestricted industrial Y transportation no military 2T Ath^ None name Multiple ownership. See attached street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Garfield County Recorder, San Juan County Recorder, Kane County —————————————————————————————————————————————————————-——-———Recorder street & number 55 South Main 88 North Main 70 North Main Panguitch city, town Monticello state Kanab 6. Representation in Existing Surveys -

Dance Hall Rock Parking EA

United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Dance Hall Rock Parking Area Development Environmental Assessment DOI-BLM-UT-0300-2013-003-EA June 2014 Location: Dance Hall Rock is located in Kane County, Utah. The nearest gateway community is Escalante, Utah, approximately 50 miles west-northwest. Salt Lake Meridian, Township 40 South, Range 7 East, Section 1. Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument 669 South Highway 89A Kanab, Utah 84741 Phone: (435) 644-1200 Fax: (435) 644-1250 Dance Hall Rock Parking Area Development DOI-BLM-UT-0300-2013-003-EA Table of Contents 1.0 Purpose and Need ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Background .............................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Need for the Proposed Action .................................................................................. 2 1.4 Purpose(s) of the Proposed Action .......................................................................... 3 1.5 Conformance with BLM Land Use Plan(s) ............................................................. 3 1.6 Relationship to Statutes, Regulations, or Other Plans ............................................. 3 1.7 Identification of Issues ............................................................................................. 4 2.0 DESCRIPTION -

Modifying the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 12/08/2017 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2017-26714, and on FDsys.gov MODIFYING THE GRAND STAIRCASE-ESCALANTE NATIONAL MONUMENT 9682 - - - - - - - BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA A PROCLAMATION In Proclamation 6920 of September 18, 1996, and exercising his authority under the Act of June 8, 1906 (34 Stat. 225) (the "Antiquities Act"), President William J. Clinton established the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in the State of Utah, reserving approximately 1.7 million acres of Federal lands for the care and management of objects of historic and scientific interest identified therein. The monument is managed by the Department of the Interior's Bureau of Land Management (BLM). This proclamation makes certain modifications to the monument. Proclamation 6920 identifies a long list of objects of historic or scientific interest within the boundaries of the monument. In the 20 years since the designation, the BLM and academic researchers have studied the monument to better understand the geology, paleontology, archeology, history, and biology of the area. The Antiquities Act requires that any reservation of land as part of a monument be confined to the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects of historic or scientific interest to be protected. Determining the appropriate protective area involves examination of a number of factors, including the uniqueness and nature of the objects, the nature of the needed protection, and the protection provided by other laws. Proclamation 6920 identifies the monument area as rich with paleontological sites and fossils, including marine and brackish water mollusks, turtles, crocodilians, lizards, dinosaurs, 2 fishes, and mammals, as well as terrestrial vertebrate fauna, including mammals, of the Cenomanian-Santonian ages, and one of the most continuous records of Late Cretaceous terrestrial life in the world. -

Hole-In-The-Rock Trail Lake Canyon – Cottonwood Canyon

Hole-in-the-Rock Trail Lake Canyon – Cottonwood Canyon © 1999, Lamont Crabtree Document created Aug. 1999 Last update Jan. 2010 Pg. 1 of 5 Hole-in-the-Rock Trail Lake Canyon – Cottonwood Canyon The Hole-in-the-Rock Trail is best known for the crevice (called the Hole-in-the-Rock) in the west wall of the 1300’ deep Colorado River gorge, which Mormon pioneers widened to make a wagon road in 1879/1880. However, it was the terrain east of the river gorge that was deemed as impassible by most of their scouts. This terrain nearly caused them to abandon their journey. When one visits this section of their trail and sees their roads carved/blasted out of solid sandstone and experiences first hand the area’s stark ruggedness, one is awed by the pioneers’ determination and ingenuity. This map is provided for those who wish to have a pioneering experience of their own. Please study the warnings carefully. The typical report I have received back from those using this map to visit the area for the first time is that even after reading the warnings, they were not prepared for the difficulty of the terrain, did not take enough water, and/or did not plan for enough time. Best wishes on your adventure. Lamont Crabtree WARNINGS!!! For your safety, please study and follow these guidelines. 1. It is highly recommended that newcomers take along a guide that is acquainted with the trail. 2. There are few road/trail signs; thus closely following map is crucial. 3. The Lake Canyon Hole-in-the-Rock Trail is a very difficult, technical four-wheel drive trail. -

Archives Summary with Images 08/02/2019 Matches 645

Archives Summary with Images 08/02/2019 Matches 645 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Condition Status Home Location A 2016.2.1 Incomplete Copy of Superior Court Minutes of Cherokee County, Third Floor Storage Record, Judicial 1834-1838 Includes crimes and sentences, Native American issues and crimes, foreclosures, and lawsuits. Also includes typed copies. A 2016.2.3 By-Laws of the Cherokee County Historical Society, Inc. Third Floor Storage Document June 13, 1995 A 2016.2.4 Excerpts from The Cherokee Advance from 1893-1910 Third Floor Storage Document A 2016.2.5 Typed Copy of the 1850 Census of Georgia, Cherokee County Third Floor Storage Document Nearly 11,650 Free Citizens Compiled by Rhea Cumming Otto Page 1 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Condition Status Home Location A 2016.2.7 January 1995 Inventory of the Cherokee County Historical Society Third Floor Storage Document A 2016.3.1 A ledger containing various bits of financial records with Fourth Floor Storage Ledger references to Bank of Canton, Reinhardt College, Canton Drug Co., a saw mill, "Will and James Pham Lumber," James Fincher, E.A. Fincher, and Mr. Darby. The records for Reinhardt expenses are the most prevalent as well as those for the Bank of Canton. The front of the ledger also contains a postage reference guide dating from 1914. The book is in fair condition apart from some pages that have become detached. Dates range from 1919 - 1931. This is the smaller of the two ledgers in this donation. A 2016.3.2 This ledger mentions financial information relating to several Fourth Floor Storage Ledger Cherokee County residents and businesses, including: Bank of Cherokee, Etowah Bank, Canton Drug Store, Jesse Fincher, Barrett House, a saw mill, Reinhardt College, C.A.