Eel-Ig Ounty Ennsy.Lvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Lehigh County

\B7 L5H3 Class _^^ ^ 7 2- CoKiightN". ^A^ COFmiGHT DEPOSIT 1/ I \ HISTORY OF < Lehigh . County . Pennsylvania From The Earliest Settlements to The Present Time including much valuable information FOR THE USE OF THE ScDoolSt Families ana Cibrarics, BY James J. Hauser. "A! Emaus, Pknna., TIMES PURIJSHING CO. 1 901, b^V THF LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, Two Copies Recfived AUG. 31 1901 COPYBIOHT ENTRV ^LASS<^M<Xa No. COPY A/ Entered according to Die Act of Congress, in the year 1901, By JAMES J. HAUSER, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. All rights reserved. OMISSIONS AND ERRORS. /)n page 20, the Lehigh Valley R. R. omitted. rag6[29, Swamp not Swoiup. Page 28, Milford not Milfod. Page ol, Popnlatioii not Populatirn. Page 39, the Daily Leader of Ailentown, omitted. Page 88, Rev. .Solomon Neitz's E. name omitted. Page i)2,The second column of area of square miles should begin with Hanover township and not with Heidelberg. ^ INTRODUCTION i It is both interesting and instructive to study the history of our fathers, to ^ fully understand through what difficulties, obstacles, toils and trials they went to plant settlements wliich struggled up to a position of wealth and prosperity. y These accounts of our county have been written so as to bring before every youth and citizen of our county, on account of the growth of the population, its resources, the up building of the institution that give character and stability to the county. It has been made as concise as possible and everything which was thought to be of any value to the youth and citizen, has been presented as best as it could be under the circumstances and hope that by perusing its pages, many facts of interest can be gathered that will be of use in future years. -

Little Lehigh Creek Visual Assessment WHITEHALL TOWNSHIP ALLENTOWN CITY

Coldwater Heritage Partnership LITTLE LEHIGH CREEK COLDWATER CONSERVATION PLAN October 2007 Acknowledgements This project was not possible without the support of the partners listed below. The Lehigh County Conservation District (LCCD) was critical in the development of the Con- servation Plan. The Watershed Specialist Rebecca Kennedy and Conservation Program Spe- cialist Erin Frederick took on significant roles beyond expectations to ensure success. They were involved in all aspects including developing the protocol for the visual stream assess- ment, surveying dozens of reaches, and designing a GIS format to better interpret the data col- lected. LCCD invested enormous amounts of resources and GIS expertise that allowed the partners to develop a Conservation Plan more comprehensive than thought possible. In addition, dedicated members of the Little Lehigh Trout Unlimited and Saucon Creek Water- shed Association volunteered numerous hours walking the main stem of the Little Lehigh Creek to assess the state of the waterway. Two members of the Saucon Creek Watershed Association deserve special recognition. These volunteers surveyed the greatest number of reaches and their dedication was greatly appreci- ated. Terry Boos Ray Follador We would like to also thank the hard work of the following volunteers that spent time assessing the creek. Bob Ditmars Greg Gliwa Allan Johnson Stacy Reed Jeff Sabo Burt Schaffer Mario Spagnoletti Powen Wang This plan was made possible through a grant from the Coldwater Heritage Partnership. The Partnership is a collabo- rative effort between the PA Fish & Boat Commission, PA De- partment of Conservation and Natural Resources, Western Penn- sylvania Watershed Protection Program and Pennsylvania Trout. -

Environmental Conservation Plan

ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION PLAN ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION PLAN Salisbury Township includes extremely important natural resources, including the mostly wooded Lehigh and South Mountains. The hydrology and other natural resources of Salisbury have great impacts upon the quality and quantity of groundwater and surface waters in the region. In particular, where groundwater reaches the surface at springs and seeps, it greatly impacts creeks and rivers and feeds into wetlands and other habitats. Salisbury Township is a stopping point for a wide variety of migratory birds, and a home and breeding grounds for many other species of birds and wildlife. Salisbury Township includes the headwaters of the Saucon and Trout Creeks. The Trout Creek and many other areas drain to the Little Lehigh Creek, which is a major drinking water source for Salisbury and Allentown. Other areas in drain directly to the Lehigh River. The mountains and areas at the base of the mountains are particularly critical for recharge of the groundwater supplies. The Lehigh County Conservation District in 2011 completed a Natural Resource Inventory (NRI) for Salisbury Township. That effort provided detailed mapping and analysis of many natural resources, including water resources, water quality, birds and habitats. A full copy of that report is available on the Township’s website. Prime Agricultural Soils The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) rates soil types for their ability to support crop farming. Soils most conducive to producing food and sustaining high crop yields are given the designation of “prime” and are rich in nutrients, well drained and permeable, as well as resistant to erosion. Prime agricultural soils typically have gently rolling to flat topography. -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

Phase II Little Lehigh Corridor

DRAFT May, 2014 Acknowledgements City of Allentown Michael Hefele – Director, Planning and Zoning Alan Salinger – Chief Planner John Mikowychok – Director of Parks and Recreation Richard Young – Director of Public Works Sara Hailstone – Director of Community and Economic Development Bernadette Debias – Allentown Business Development Manager Allentown Economic Development Corporation Scott Unger – Executive Director Anthony Durante – Economic Development Specialist Project Team Camoin Associates Bergmann Associates Innovation Policyworks Thomas P. Miller Associates Funding for this project has been provided by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Sustainable Housing and Communities, through the Lehigh Valley Economic Development Corporation. CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. i Context ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Strategic Location ...................................................................................................................................... 1 History ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Reindustrialization Strategy Phases ............................................................................................................ -

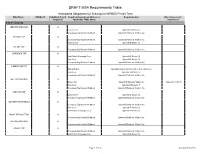

DRAFT MS4 Requirements Table

DRAFT MS4 Requirements Table Anticipated Obligations for Subsequent NPDES Permit Term MS4 Name NPDES ID Individual Permit Impaired Downstream Waters or Requirement(s) Other Cause(s) of Required? Applicable TMDL Name Impairment Adams County ABBOTTSTOWN BORO No Beaver Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) BERWICK TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) Beaver Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) BUTLER TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) CONEWAGO TWP No South Branch Conewago Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Plum Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) CUMBERLAND TWP No Willoughby Run Appendix E-Organic Enrichment/Low D.O., Siltation (5) Rock Creek Appendix E-Nutrients (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) GETTYSBURG BORO No Stevens Run Appendix E-Nutrients, Siltation (5) Unknown Toxicity (5) Rock Creek Appendix E-Nutrients (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) HAMILTON TWP No Beaver Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) MCSHERRYSTOWN BORO No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) Plum Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) South Branch Conewago Creek Appendix E-Siltation (5) MOUNT PLEASANT TWP No Chesapeake Bay Nutrients/Sediment Appendix D-Nutrients, Siltation (4a) NEW OXFORD BORO No -

69 Dams Removed in 2020 to Restore Rivers

69 Dams Removed in 2020 to Restore Rivers American Rivers releases annual list including dams in California, Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin for a total of 23 states. Nationwide, 1,797 dams have been removed from 1912 through 2020. Dam removal brings a variety of benefits to local communities, including restoring river health and clean water, revitalizing fish and wildlife, improving public safety and recreation, and enhancing local economies. Working in a variety of functions with partner organizations throughout the country, American Rivers contributed financial and technical support in many of the removals. Contact information is provided for dam removals, if available. For further information about the list, please contact Jessie Thomas-Blate, American Rivers, Director of River Restoration at 202.347.7550 or [email protected]. This list includes all dam removals reported to American Rivers (as of February 10, 2021) that occurred in 2020, regardless of the level of American Rivers’ involvement. Inclusion on this list does not indicate endorsement by American Rivers. Dams are categorized alphabetically by state. Beale Dam, Dry Creek, California A 2016 anadromous salmonid habitat assessment stated that migratory salmonids were not likely accessing habitat upstream of Beale Lake due to the presence of the dam and an undersized pool and weir fishway. In 2020, Beale Dam, owned by the U.S. Air Force, was removed and a nature-like fishway was constructed at the upstream end of Beale Lake to address the natural falls that remain a partial barrier following dam removal. -

January 1986 Vol

rr Pennsylvania !tao'im/80t 'NGI The Keystone State's Official Fishing Magazine w -*-**< Straight TalK and Wildlife Service and the National control, fish pathology, and fish Marine Fisheries Service, a Great culture are being utilized in the Lakes Caucus of state directors listed Strategic Management Plan. A good and reviewed 40 major areas of look at the predator/forage STRATEGIC GREAT concern relating to management of communities in Lake Erie is very high LAKES FISHERIES the Great Lakes fishery. on our agenda, as well as possibilities In the process of identifying the of use of common advisories of MANAGEMENT PLAN critical issues and strategies that contaminant levels in fish flesh. pertain to the Great Lakes fisheries We have seen considerable give and In June 1981, 12 state, provincial, and for the rest of the 1980s, that caucus take over the years relative to Lake federal agencies signed a Joint determined that the previously Erie, and these things do drag on; but Strategic Plan for the management of adopted Strategic Great Lakes that is unavoidable. Our own staff is the Great Lakes fisheries. This was the Fisheries Management Plan deeply committed to working on result of three years of hard work by (SGLFMP) was still relevant, but that lakewide management plans with fish steering committees, a Committee of a review of the progress achieved in community objectives, and these, of the Whole, working groups, and the the plan's implementation was much course, will have to be general, Great Lakes Fishery Commission. needed. The caucus concluded that flexible, and dynamic. -

Class a Wild Trout Waters Created: August 16, 2021 Definition of Class

Class A Wild Trout Waters Created: August 16, 2021 Definition of Class A Waters: Streams that support a population of naturally produced trout of sufficient size and abundance to support a long-term and rewarding sport fishery. Management: Natural reproduction, wild populations with no stocking. Definition of Ownership: Percent Public Ownership: the percent of stream section that is within publicly owned land is listed in this column, publicly owned land consists of state game lands, state forest, state parks, etc. Important Note to Anglers: Many waters in Pennsylvania are on private property, the listing or mapping of waters by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission DOES NOT guarantee public access. Always obtain permission to fish on private property. Percent Lower Limit Lower Limit Length Public County Water Section Fishery Section Limits Latitude Longitude (miles) Ownership Adams Carbaugh Run 1 Brook Headwaters to Carbaugh Reservoir pool 39.871810 -77.451700 1.50 100 Adams East Branch Antietam Creek 1 Brook Headwaters to Waynesboro Reservoir inlet 39.818420 -77.456300 2.40 100 Adams-Franklin Hayes Run 1 Brook Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 31 Bedford Bear Run 1 Brook Headwaters to Mouth 40.207730 -78.317500 0.77 100 Bedford Ott Town Run 1 Brown Headwaters to Mouth 39.978611 -78.440833 0.60 0 Bedford Potter Creek 2 Brown T 609 bridge to Mouth 40.189160 -78.375700 3.30 0 Bedford Three Springs Run 2 Brown Rt 869 bridge at New Enterprise to Mouth 40.171320 -78.377000 2.00 0 Bedford UNT To Shobers Run (RM 6.50) 2 Brown -

Saucon Creek Tmdl Alternatives Report

SAUCON CREEK TMDL ALTERNATIVES REPORT Lehigh Valley Planning Commission February 2011 -1- -2- SAUCON CREEK TMDL ALTERNATIVES REPORT Lehigh Valley Planning Commission in cooperation with Lehigh County Conservation District February 2011 The preparation of this report was financed through a grant agreement with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. -3- LEHIGH VALLEY PLANNING COMMISSION Steven L. Glickman, Chair Robert A. Lammi, Vice Chair Kent H. Herman, Treasurer Ron Angle Benjamin F. Howells, Jr. Norman E. Blatt, Jr., Esq. Edward D. Hozza, Jr. Becky Bradley (Alternate) Terry J. Lee Dean N. Browning Ronald W. Lutes John B. Callahan Earl B. Lynn Donald Cunningham Jeffrey D. Manzi John N. Diacogiannis Ross Marcus (Alternate) Percy H. Dougherty Kenneth M. McClain Liesel Dreisbach Thomas J. Nolan Karen Duerholz Ray O’Connell Charles W. Elliott, Esq. Salvatore J. Panto, Jr. Cindy Feinberg (Alternate) Edward Pawlowski Charles L. Fraust Stephen Repasch George F. Gemmel Michael Reph Matthew Glennon Ronald E. Stahley Armand V. Greco John Stoffa Michael C. Hefele (Alternate) Donna Wright Darlene Heller (Alternate) LEHIGH VALLEY PLANNING COMMISSION STAFF Michael N. Kaiser, AICP Executive Director ** Geoffrey A. Reese, P.E. Assistant Director Olev Taremäe Chief Planner Joseph L. Gurinko, AICP Chief Transportation Planner Thomas K. Edinger, AICP GIS Manager/Transportation Planner * Lynette E. Romig Senior GIS Analyst * Susan L. Rockwell Senior Environmental Planner Michael S. Donchez Senior Transportation Planner David P. Berryman Senior Planner Teresa Mackey Senior Planner * Travis I. Bartholomew, EIT Stormwater Planner Wilmer R. Hunsicker, Jr. Senior Planning Technician Bonnie D. Sankovsky GIS Technician Anne L. Esser, MBA Administrative Assistant * Alice J. Lipe Senior Planning Technician Kathleen M. -

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - November 2018

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - November 2018 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 7.91 Armstrong Birch Run Allegheny River Headwaters dnst to mouth 41.033300 -79.619414 1.10 Armstrong Bullock Run North Fork Pine Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.879723 -79.441391 1.81 Armstrong Cornplanter Run Buffalo Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.754444 -79.671944 1.76 Armstrong Cove Run Sugar Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.987652 -79.634421 2.59 Armstrong Crooked Creek Allegheny River Headwaters to conf Pine Rn 40.722221 -79.102501 8.18 Armstrong Foundry Run Mahoning Creek Lake Headwaters -

Pennsylvania Highlands Region Canoeing Stream Inventory

Pennsylvania Highlands Region Canoeing Stream Inventory PRELIMINARY November 8, 2006 This document is a list of all streams in the Pennsylvania Highlands region, annotated to indicate canoeable streams and stream charac- teristics. Streams in bold type are paddleable. The others, while pos- sible paddleable, are not generally used for canoeing. Note that some of these streams become canoeable only after heavy rain or snow melt. Others have longer seasons. Some, like the Dela- ware, Schuylkill and Lehigh Rivers, are always paddeable, except when fl ooding or frozen. This inventory uses the standardized river rating system of American Whitewater. It is not intended as paddlers guide. Other sources of information, including information on river levels. Sources: My own personal fi eld observations over 30 years of paddling. I have paddled a majority of the streams listed. Keystone Canoeing, by Edward Gertler, 2004 edition. Seneca Press. American Whitewater, National River Database. Eric Pavlak November, 2006 ID Stream Comments 1. Alexanders Spring Creek 2. Allegheny Creek 3. Angelica Creek 4. Annan Run 5. Antietam Creek Might be high water runnable 6. Back Run 7. Bailey Creek 8. Ball Run 9. Beaver Creek 10. Beaver Run 11 Beck Creek 12. Bells Run 13. Bernhart Creek 14. Bieber Creek 15. Biesecker Run 16. Big Beaver Creek 17. Big Spring Run 18. Birch Run 19. Black Creek 20. Black Horse Creek 21. Black River 22. Boyers Run 23. Brills Run 24. Brooke Evans Creek 25. Brubaker Run 26. Buck Run 27. Bulls Head Branch 28. Butter Creek 29. Cabin Run 30. Cacoosing Creek 31. Calamus Run 32.