Race, Space, and Surveillance: a Response to #Livingwhileblack: Blackness As Nuisance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emily J.H. Contois

Updated June 2021 EMILY J.H. CONTOIS 800 S. Tucker Drive, Department of Media Studies, Oliphant Hall 132, Tulsa, OK 74104 [email protected] | emilycontois.com | @emilycontois — EDUCATION — Ph.D. Brown University, 2018 American Studies with Gender & Sexuality Studies certificate, Advisor: Susan Smulyan M.A. Brown University, 2015 American Studies M.L.A. (Award for Excellence in Graduate Study), Boston University, 2013 Gastronomy, Thesis Advisor: Warren Belasco, Reader: Carole Counihan M.P.H. University of California, Berkeley, 2009 Public Health Nutrition B.A. (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa), University of Oklahoma, 2007 Letters with Medical Humanities minor, Thesis Advisor: Julia Ehrhardt — APPOINTMENTS — Chapman Assistant Professor, Media Studies, The University of Tulsa, 2019-2022 Assistant Professor, Media Studies, The University of Tulsa, 2018-Present — PUBLICATIONS — Books 2020: Diners, Dudes, and Diets: How Gender and Power Collide in Food Media and Culture (University of North Carolina Press). Reviewed in: International Journal of Food Design (2021), Advertising & Society Quarterly (Author Meets Critics 2021), Men and Masculinities (2020), Library Journal (2020); Named one of Helen Rosner’s “Great Food-ish Nonfiction 2020;” Included on Civil Eats, “Our 2020 Food and Farming Holiday Book Gift Guide” and Food Tank’s “2020 Summer Reading List;” Featured in: Vox, Salon, Elle Paris, BitchMedia, San Francisco Chronicle, Tulsa World, Currant, BU Today, Culture Study, InsideHook, Nursing Clio Edited Collections 2022: {forthcoming} Food Instagram: Identity, Influence, and Negotiation, co-edited with Zenia Kish (University of Illinois Press). Refereed Journal Articles 2021: {forthcoming} “Real Men Don’t Eat Quiche, Do They? Food, Fitness, and Masculinity Crisis in 1980s America,” European Journal of American Culture’s 40th anniversary special issue. -

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 80 5Th Avenue, 521 New York, NY 10011 Phone: 917-741-3209 E-Mail: [email protected]

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 80 5th Avenue, 521 New York, NY 10011 Phone: 917-741-3209 E-Mail: [email protected] www.nataliapetrzela.com Education Ph.D. Stanford University, History, 2009. M.A. Stanford University, History, 2004. B.A. Columbia College, History, cum laude, 2000. Experience • Assistant Professor of Education Studies and History, The New 2009-present School • Co-founder, HealthClass2.0 (www.healthclass.org) 2011-present • Spanish Teacher, P.S./I.S. 111 2001-2002 Research Interests • U.S. History, culture, politics, education, gender, the body, conservatism, capitalism, sexuality, race, ethnicity, language, consumption, the West, Latinos, youth, family, public scholarship, civic engagement Books • Classroom Wars: Language, Sex, and the Making of Modern Political 2015 Culture, Oxford University Press Peer-Reviewed Articles and Book Chapters • “An Intellectual History of the Gym, (Thanks, Gender!),” eds. Andrew Hartman and Raymond Haberski, No Things But in Ideas: United States Intellectual History, under editorial review. • “Sex, Spirituality, and the Popularization of Yoga in Modern America” [under review] • “HealthClass2.0: Crossing Boundaries Through Campus-Based Civic September 2015 Engagement,” Anthropology Now, Vol. 7 No. 2. • “Revisiting the Rightward Turn: Max Rafferty, Education, and May 2014 Modern American Politics,” The Sixties: A Journal of History, Politics, and Culture, Vol. 6, No.2. • With Sarah Manekin, “The Accountability Partnership: Writing and October 2013 Surviving in the Digital Age,” in Dougherty, Jack, and Nawrotzki, Natalia Mehlman Petrzela Page 2 Kristin, eds., Writing History in the Digital Age, University of Michigan Digital Humanities Series • “Before the Federal Bilingual Education Act: Legislation and Lived November 2010 Experience,” Immigration and Education: A Special Issue of the Peabody Journal of Education, Vol.85, No.4., 406-424. -

Providence RHODE ISLAND

2016 On Leadership Providence RHODE ISLAND 2016 OAH Annual Meeting Onsite Program RHODE ISLAND CONVENTION CENTER | APRIL 7–10 BEDFORD/ST. MARTIN’S For more information or to request your complimentary review copy now, stop by Booth #413 & 415 or visit us online at 2016 macmillanhighered.com/OAHAPRIL16 NEW Bedford Digital Collections The sources you want from the publisher you trust. Bedford Digital Collections offers a fresh and intuitive approach to teaching with primary sources. Flexible and affordable, this online repository of discovery-oriented projects can be easily customized to suit the way you teach. Take a tour at macmillanhighered.com/bdc Primary source projects Revolutionary Women’s Eighteenth-Century Reading World War I and the Control of Sexually Transmitted and Writing: Beyond “Remember the Ladies” Diseases Karin Wulf, College of William and Mary Kathi Kern, University of Kentucky The Antebellum Temperance Movement: Strategies World War I Posters and the Culture of American for Social Change Internationalism David Head, Spring Hill College Julia Irwin, University of South Florida The California Gold Rush: A Trans-Pacific Phenomenon War Stories: Black Soldiers and the Long Civil Rights David Igler, University of California, Irvine Movement Maggi Morehouse, Coastal Carolina University Bleeding Kansas: A Small Civil War Nicole Etcheson, Ball State University The Social Impact of World War II Kenneth Grubb, Wharton County Junior College What Caused the Civil War? Jennifer Weber, University of Kansas, Lawrence The Juvenile Delinquency/Comic -

History of Education Society Annual Meeting October 22 – 25, 2009

History of Education Society Annual Meeting October 22 – 25, 2009 Doubletree Hotel Philadelphia, Pennsylvania History of Education Society Annual Meeting October 22-25, 2009 Doubletree Hotel Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Conference Sponsors New York University, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development University of Hawai’i College of Education University of Pennsylvania, Graduate School of Education Temple University, College of Education Random House Books Yale University Press Local Arrangements Committee Marybeth Gasman, University of Pennsylvania (Chair) Michael Clapper, St. Joseph’s University John Puckett, University of Pennsylvania Christine Woyshner, Temple University Book Exhibit Director Sherman Dorn, University of South Florida Graduate Student Committee Michelle Purdy, Emory University (Chair) Daniela Blei, Stanford University Deidre Flowers, Teachers College, Columbia University Michael Hevel, University of Iowa 2 Frank Honts, University of Wisconsin--Madison Seabrook Jones, University of Delaware Special Thanks to John Press, New York University, for his help in planning the meeting Karen Lech, Doubletree Hotel History of Education Society Officers, 2008-2009 President Eileen Tamura, University of Hawaii Past President Harold Wechsler, New York University Vice President and Program Chair Jonathan Zimmerman, New York University Vice-President Elect Philo Hutcheson, Georgia State University Secretary-Treasurer Robert Hampel, University of Delaware Directors Harold Wechsler, New York University (2009) Andrea Walton, Indiana University (2007-2009) Kim Tolley, Notre Dame de Namur University (2008-2010) Christine Ogren, University of Iowa (2009-2011) History of Education Quarterly Editorial Staff Senior Editor James D. Anderson, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Co-Editors Yoon K. Pak, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Christopher Span, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Book Review Editor Katrina M. -

San Francisco Program 2014

Crossing Divides Annual Conference March 12 - 16, 2014 San Francisco, California i ASEH is very grateful to the University of California- Table of Contents Berkeley and Stanford University for hosting this We are also very grateful to the following individuals for conference. their support of this conference: Welcome from the Local Arrangements Committee 2 In addition, we thank the following sponsors for their Anonymous generous contributions: Colin Milburn, University of California-Davis, the Gary Snyder Chair A Note from the Program Committee 4 Arizona State University Public History Program John Reiger, Ohio University California Historical Society Edmund Russell, University of Kansas California State Polytechnic University-Pomona Jeanie Sherwood, Davis, California Conference at a Glance 5 California State University-East Bay, Departments of Garrison Sposito, University of California, Berkeley, The Anthropology, Environmental Studies, Geography, and Betty and Isaac Barshad Chair in Soil Science History Joel Tarr, Carnegie Mellon University Conference Information 6 Carnegie Melon University Center for Ecological History, Renmin University of China Program design by Roxane Barwick, Arizona State Location and Lodging 6 Center of the American West, University of Colorado- University Registration 6 Boulder Transportation 6 Forest History Society Photos courtesy Travel San Francisco, Lisa Mighetto, and Local Weather 7 John Muir Center, University of the Pacific Laura A. Watt Cancellations 7 La Boulange de Yerba Buena Child Care 7 Massachusetts -

Gutfreund Dissertation Draft

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Language Education, Race, and the Remaking of American Citizenship in Los Angeles, 1900- 1968 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5zd66224 Author Gutfreund, Zevi Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Language Education, Race, and the Remaking of American Citizenship in Los Angeles, 1900-1968 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Zevi Moses Gutfreund 2013 © Copyright by Zevi Moses Gutfreund 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Language Education, Race, and the Remaking of American Citizenship in Los Angeles, 1900-1968 by Zevi Moses Gutfreund Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Stephen Aron, Chair This dissertation uses language instruction in Los Angeles as a lens through which to explore assimilation, immigration, and what it means to be an American. It draws from sources such as curricular materials, court records, correspondence, blue book exams, and student newspapers in the city of angels’ Anglo, Mexican, and Japanese American communities. They launched language experiments that attracted national attention from 1900 to 1968, the year of the federal Bilingual Education Act and the “Chicano Blowouts” in East Los Angeles. While many scholars have pointed to those events as crucial moments in the origins of the modern -

The Writing on the Wall Orozco, Benton, and Arnautoff

3/13/2020 The Writing on the Wall - Public Seminar NEW SCHOOL HISTORIES The Writing on the Wall Orozco, Benton, and Arnautoff September 25, 2019 Jennifer Wilson 0 By now, most people who care about public art and human rights will have heard about the San Francisco School Board’s recent decisions to destroy, and subsequently to cover The Life of George Washington, a set of 13 murals painted in 1936 by Victor Arnautoff for George Washington High School. The most disputed sections depict Washington encouraging white settlers in their westward march, over the figure of a dead Native American, and images of Washington’ slaves working in the fields of Mount Vernon. Student and activist groups have campaigned for the removal of the murals, arguing they were detrimental to the education and well-being of students of color, who had to confront these images as they walked the halls or ascended the staircase. On the other side of the debate, art historians and preservationists point to the historic and aesthetic values of the WPA mural. They argue that, unlike statues of Confederate soldiers that celebrate perpetrators of injustice, Arnautoff’s murals illustrate the impacts of the country’s founding on African Americans and Native Americans and provide opportunities to develop a more nuanced understanding of U.S. history. The debate over the mural brings to mind a well-known controversy in The New School’s past: the censoring of parts of Jose Clemente Orozco’s murals in the 1950s in response to political pressures during the Cold War. In 1953 a committee of the Board of Directors announced “the existence of the murals was clearly a divisive element and has caused considerable annoyance,” and ordered President Hans Simons to cover the offending section. -

2017 OAH Annual Meeting

2017 OAH Annual Meeting New Orleans, Louisiana April 6–9, 2017 BEDFORD/ ST. MARTIN’S Digital options you can customize HISTORY2017 to your course For more information or to request your review copy, please visit us at OAH or at macmillanlearning.com/OAH2017 Flexible and affordable, this online repository of discovery-oriented proj- ects offers: • Primary Sources , both canonical and unusual documents (texts, visuals, maps, and in the online version, audio and video). • Customizable Projects you can assign individually or in any combination, and add your own instructions and additional sources. • Easy Integration into your course management system or Web site, and offers one-click assigning, assessment with instant feedback, and a convenient gradebook. New Custom Print Option Choose up to two document projects from the collection and add them in print to a Bedford/St. Martin’s title free of charge, add additional modules to your print text at a nominal extra cost, or select an unlimited number of modules to be bound together in a custom reader. Built as an interactive learning experience, LaunchPad prepares students for class and exams while giving instructors the tools they need to quickly set up a course, shape content to a syllabus, craft presentations and lectures, assign and assess homework, and guide the progress of individual students and the class as a whole. Featuring An interactive e-Book integrating all student resources, including: • Newly redesigned LearningCurve adaptive quizzing, with questions that link back to the e-book so students can brush up on the reading when they get stumped by a question • More auto-graded source-based questions including images and excerpts from documents as prompts for student analysis. -

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 80 5Th Avenue, 521! New York, NY 10011 Phone: 917-741-3209 ! E-Mail: [email protected]

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 80 5th Avenue, 521! New York, NY 10011 Phone: 917-741-3209 ! E-Mail: [email protected] www.nataliapetrzela.com Education Ph.D. Stanford University, History, 2009. M.A. Stanford University, History, 2004. B.A. Columbia College, History, cum laude, 2000. Experience • Associate Professor of History July 2017-present • Assistant Professor of Education Studies and History 2009-2017 • Co-founder, HealthClass2.0 (www.healthclass.org) 2011-2016 • Spanish Teacher, P.S./I.S. 111 2001-2002 Research Interests • U.S. History, culture, politics, education, gender, the body, conservatism, capitalism, sexuality, race, ethnicity, language, consumption, the West, Latinos, youth, family, public scholarship, civic engagement Books • Classroom Wars: Language, Sex, and the Making of Modern Political 2015, paperback 2017 Culture, Oxford University Press Peer-Reviewed Articles and Book Chapters • “An Intellectual History of the Gym, (Thanks, Gender!),” eds. Forthcoming Andrew Hartman and Raymond Haberski, No Things But in Ideas: United States Intellectual History, Cornell University Press. • “’The Siren Song of Yoga’: Sex, Spirituality, and the Popularization Forthcoming of Yoga in Modern America,” Pacific Historical Review • “HealthClass2.0: Crossing Boundaries Through Campus-Based Civic September 2015 Engagement,” Anthropology Now, Vol. 7 No. 2. • “Revisiting the Rightward Turn: Max Rafferty, Education, and May 2014 Modern American Politics,” The Sixties: A Journal of History, Politics, and Culture, Vol. 6, No.2. • With Sarah Manekin, “The Accountability Partnership: Writing and October 2013 Surviving in the Digital Age,” in Dougherty, Jack, and Nawrotzki, Natalia Mehlman Petrzela Page 2 Kristin, eds., Writing History in the Digital Age, University of Michigan Digital Humanities Series • “Before the Federal Bilingual Education Act: Legislation and Lived November 2010 Experience,” Immigration and Education: A Special Issue of the Peabody Journal of Education, Vol.85, No.4., 406-424. -

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 80 5Th Avenue, 521 New York, NY 10011 Phone: 917-741-3209 Fax: 212-229-5929 E-Mail: [email protected]

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 80 5th Avenue, 521 New York, NY 10011 Phone: 917-741-3209 Fax: 212-229-5929 E-Mail: [email protected] Education Ph.D. Stanford University, History, 2009 M.A. Stanford University, History, 2004 Dissertation: “Origins of the Culture Wars: Sex, Language, School, and State in California, 1968-78” Committee: Estelle Freedman; Albert Camarillo; Joy Ann Williamson B.A. Columbia College, History, cum laude, 2000 Experience • Assistant Professor of History, Eugene Lang College The New 2014-present School for Liberal Arts • Assistant Professor of Education Studies and History, Eugene Lang 2009-2014 College The New School for Liberal Arts • Co-chair, Education Studies, Eugene Lang College The New 2010-2013 School for Liberal Arts • Spanish teacher, P.S/I.S. 111, New York City Department of 2001-2002 Education Publications Books • Classroom Wars: Language, Sex, and the Making of Modern Political Forthcoming, 2015 Culture, Oxford University Press Articles and Book Chapters • “Revisiting the Rightward Turn: Max Rafferty, Education, and May 2014 Modern American Politics,” The Sixties: A Journal of History, Politics, and Culture, Vol. 6, No.2. • With Sarah Manekin, “The Accountability Partnership: Writing and October 2013 Surviving in the Digital Age,” in Dougherty, Jack, and Nawrotzki, Kristin, eds., Writing History in the Digital Age, University of Michigan Digital Humanities Series • “Before the Federal Bilingual Education Act: Legislation and Lived November 2010 Experience,” Immigration and Education: A Special Issue of the Peabody Journal of Education, Vol.85, No.4., 406-424. • “’Sex Ed… and the Reds?’ Reconsidering the Anaheim Battle over May 2007 Sex Education, 1962-1969,” History of Education Quarterly, Vol. -

Conference Program

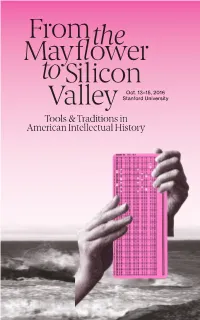

Oct. 13–15, 2016 Stanford University Tools & Traditions in American Intellectual History 1 Welcome to the 2016 Society for United States Intellectual History (S-USIH)’s annual conference! Now in its eighth year, the S-USIH conference is already well known in the historical profession for its welcom- ing atmosphere, rigorous level of discussion, and wide ranging set of interests. In the program that follows, you will find scholars engaging everything from Darwin to Deconstruction, hip hop to the Whole Earth Catalog. Over 100 original papers will be presented, spanning all aspects of American thought, with plenary sessions on gender, Puritanism, technology, and presidential politics. We expect you’ll find plenty of food for thought. Sincerely, 2016 S-USIH Conference Committee Jennifer Burns, Chair, Stanford University Claire Rydell Arcenas, University of Montana Lilian Calles Barger, Independent Scholar Jeffrey Sklansky, University of Illinois at Chicago Ethan Schrum, Azusa Pacific University 2 Schedule Overview Thursday, October 13 4–5pm Welcome Reception, appetizers and drinks Conference registration opens 5:30–7pm Opening Keynote Address Fred Turner, Stanford University, “Network Celebrity: Entrepreneurship and the New Public Intellectuals” 7:15pm Shuttles to Cardinal Hotel, downtown Palo Alto 8pm Stanford Marguerite Shuttle service also available Friday, October 14 8am Shuttle pickups from Cardinal Hotel, Stanford Guest House Stanford Marguerite Shuttle service also available departing from CalTrain Station (Y Limited and P Express) -

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 80 5Th Avenue, 521 New York, NY 10011 Phone: 917-741-3209 E-Mail: [email protected]

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela 80 5th Avenue, 521 New York, NY 10011 Phone: 917-741-3209 E-Mail: [email protected] www.nataliapetrzela.com Education Ph.D. Stanford University, History, 2009. M.A. Stanford University, History, 2004. B.A. Columbia College, History, cum laude, 2000. Experience • Assistant Professor of Education Studies and History, The New 2009-present School • Co-founder, HealthClass2.0 (www.healthclass.org) 2011-present • Spanish Teacher, P.S./I.S. 111 2001-2002 Research Interests • U.S. History, culture, politics, education, gender, the body, conservatism, capitalism, sexuality, race, ethnicity, language, consumption, the West, Latinos, youth, family, public scholarship, civic engagement Books • Classroom Wars: Language, Sex, and the Making of Modern Political 2015 Culture, Oxford University Press Peer-Reviewed Articles and Book Chapters • “Sex, Spirituality, and the Popularization of Yoga in Modern America” [UNDER FINAL REVIEW, contract signed for edited volume, Devotions and Desires, with University of Pennsylvania Press] • “HealthClass2.0: Crossing Boundaries Through Campus-Based Civic September 2015 Engagement,” Anthropology Now, Vol. 7 No. 2. • “Revisiting the Rightward Turn: Max Rafferty, Education, and May 2014 Modern American Politics,” The Sixties: A Journal of History, Politics, and Culture, Vol. 6, No.2. • With Sarah Manekin, “The Accountability Partnership: Writing and October 2013 Surviving in the Digital Age,” in Dougherty, Jack, and Nawrotzki, Kristin, eds., Writing History in the Digital Age, University of Natalia Mehlman Petrzela Page 2 Michigan Digital Humanities Series • “Before the Federal Bilingual Education Act: Legislation and Lived November 2010 Experience,” Immigration and Education: A Special Issue of the Peabody Journal of Education, Vol.85, No.4., 406-424.