FEMA Reports and Studies Concerning Risks from Geomagnetic Storms and Solar Flares, 2010*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Space Weather Observing Systems: Current Capabilities And

REPORT ON SPACE WEATHER OBSERVING SYSTEMS: CURRENT CAPABILITIES AND REQUIREMENTS FOR THE NEXT DECADE April 2013 Prepared by the Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research National Space Weather Program Council - Joint Action Group for Space Environmental Gap Analysis In response to a request by the Office of Science and Technology Policy Executive Office of the President NATIONAL SPACE WEATHER PROGRAM COUNCIL (NSWPC) MR. SAMUEL P. WILLIAMSON, Chairman MS. VICTORIA COX* Federal Coordinator for Meteorology Department of Transportation DR. JOHN HAYES* DR. RICHARD FISHER* Department of Commerce National Aeronautics and Space Administration DR. FRED LEWIS* DR. TIMOTHY KILLEEN* Department of Defense National Science Foundation MR. W. RANDALL BELL MS. MARY KICZA Department of Energy Department of Commerce Alternate MS. ROBIN FINEGAN* DR. HARROLD BELL Department of Homeland Security National Aeronautics and Space Administration Alternate MR. JAMES F. DEVINE* MR. DAMON WELLS* Department of the Interior Office of Science and Technology Policy Observer MR. KENNETH HODGKINS MS. GRACE HU Department of State Office of Management and Budget Observer MR. MICHAEL F. BONADONNA, Executive Secretary Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research *Denotes individuals who have rotated off the National Space Weather Program Council. This document was prepared by the Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research (OFCM) at the request of the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) in the Executive Office of the President. OSTP retains distribution control of the report. Do not copy or distribute this document outside of U.S. Government agencies without express permission from OSTP. -

Analysis on Plasma Sheath Formation and Its Effects on Radio Communications

Analysis on Plasma Sheath Formation and its Effects on Radio Communications a project presented to The Faculty of the Department of Aerospace Engineering San José State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Aerospace Engineering by Jared Delatorre Wakefield Sagaga May 2018 approved by Dr. Nikos Mourtos Faculty Advisor Table of Contents Chapter 1. Literature Review ................................................................................................. 3 1.0 Project Objective ................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 1.3 Methodology ........................................................................................................................10 Chapter 2. Analysis .............................................................................................................. 12 2.0 Analytical ..............................................................................................................................12 2.0.1 Euler Equations .........................................................................................................13 2.0.2 Navier-Stokes Equations ...........................................................................................14 -

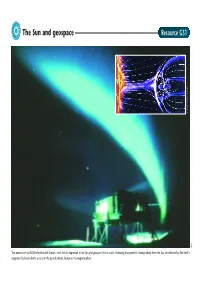

10. Geospace Resource

The Sun and geospace Resource GS1 K. Endo/Nikkei Science BAS The aurora over the BAS Halley Research Station. Inset: Artist’s impression of the Sun and geospace (not to scale) illustrating how particles flowing radially from the Sun are deflected by the Earth’s magnetic field which forms a cavity in the particle stream, known as the magnetosphere. Solar wind – magnetosphere interaction Resource GS2 An illustration of the inter- action between the solar wind and magnetosphere. Solar wind streamlines are deflected by a shock wave to flow around the magnetosphere in a turbulent layer known as the magnetosheath. Some solar wind plasma leaks inside the magnetosphere. In the magnetosphere particles are guided in spiral helical trajectories along magnetic field lines. Some of these precipitate into the atmosphere to create the aurora. SUN BAS The aurora over Antarctica Resource GS3 Professor L.A. Frank (University of Iowa) A satellite view of Antarctica showing the aurora encircling it The effects of space weather on human activity Resource GS4 Effects on satellites radiation belts. Similarly, the continuous the Hubble Space Telescope. These boosts Satellites often operate in the space bombardment by atoms in the thin upper again add to costs. environment for many years. As a result, atmosphere can alter orbits and wear they can sustain long-term exposure surfaces away. Some materials become Effects on power systems effects in addition to special ‘space storm’ brittle from long-term exposure to solar Electric power systems on the ground problems. Depending upon their orbit, ultraviolet light above the protective can be affected by the enhanced satellite electronic components, solar absorbing atmosphere of Earth. -

The Spacecraft Communications Blackout Problem Encountered During Passage Or Entry of Planetary Atmospheres

IPN Progress Report 42-150 August 15, 2002 The Spacecraft Communications Blackout Problem Encountered during Passage or Entry of Planetary Atmospheres D. D. Morabito1 During the Mars Pathfinder mission, there was a 30-second period in which the 8.4-GHz (X-band) communications link to Earth was lost during the atmospheric entry phase. An analysis of the Mars Pathfinder reconstructed flight profile using aero-thermodynamic tools provided estimates of the electron densities in the stag- nation and wake regions of the spacecraft. For the wake region, where the low-gain antenna used to communicate with Earth was located, the electron-density esti- mates exceeded the critical X-band electron density during the first 20 seconds of the 30-second blackout period. High Doppler dynamics and low signal-to-noise ratio may have contributed to the blackout during the last 10 seconds. Thus, at least part of the Mars Pathfinder communications blackout during entry was possibly due to the sheath of charged particles generated by heating incurred by the shock. The up- coming Mars Exploration Rover (MER) missions, MER-A and MER-B, scheduled for 2003 launches, are not expected to experience communication blackouts due to charged particles during their entry phases into the Martian atmosphere in 2004. The estimated peak electron densities expected for MER lie about three orders of magnitude below the critical X-band electron density required for blackout. I. Introduction Several missions have flown or are being planned to fly in which space probes will descend into planetary atmospheres to realize a variety of objectives. Such missions include landers, rovers, and airplanes, as well as orbiting spacecraft, which will use the planetary atmosphere to slow them down and enable aero- capture in order to save fuel to bring them into orbit. -

Apollo 13 Mission Report

M RAPP MSC-02680 RITA ' ' NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION '. APOLLO 13 MISSION REPORT ' . -.I DISTRIBUTION AND REFERENCING This paper is not uitable for general distribution referencing. It may be referenced � c1r _ only 111 other workmg correspondence and documents by participating organizations. • ·� . t , ' • . c c-��� MANNED SPACECRAFT CENTER . ) v �-c: • .. (.' HOUSTON.TEXAS .... v�·s··..... .... ... SE PTEMBER 1970 - ·:.:-:- :-:·: ·:.:. :· : :· . ·.·.·.·.·.·.·.·.·.·.·.·�: �: �:�: �::: �: �: �:�: �: � ·.·.·.·.·.·.·.·.·.·.·.· � �� �� �� � �� � �� � �� �� �� �� � APOLLO SPACECRAFT FLIGHT HISTORY Mission S;Eacecraft Descri;Etion Launch date Launch site PA-l BP-6 First pad abort Nov. 7, 1963 White Sands Missile Range, N. Mex. A-001 BP-12 Transonic abort May 13, 1964 White Sands Missile Range, N. Mex. AS-101 BP-13 Nominal launch and May 28, 1964 Cape Kennedy, exit environment Fla. AS-102 BP-15 Nominal launch and Sept. 18, 1964 Cape Kennedy, exit environment Fla. A-002 BP-23 Maximum dynamic Dec. 8, 1964 White Sands pressure abort f..�ssile Range, N. Mex. AS-103 BP-16 Micrometeoroid Feb. 16' 1965 Cape Kennedy, experiment Fla. A-003 BP-22 Low-altitude abort May 19, 1965 White Sands (planned high- Missile Range, a1ti tude abort) N. Mex. AS-104 BP-26 Mi.crometeoroid May 25' 1965 Cape Kennedy, experiment and Fla. service module RCS launch envirorun.ent PA-2 BP-23A Second pad abort June 29, 1965 White Sands Missi.le Range, N. Mex. AS-105 BP-9A Micrometeoroid July 30, 1965 Cape Kennedy, experiment and Fla. service module RCS launch environment A-004 SC-002 Power-on tumbling Jan. 20, 1966 White Sands boundary abort Missile Range, N. Mex. � AS-201 SC-009 Supercircular Feb. -

Study on Radio Frequency Communication Blackout Environments for a Small Deep Space Probe During an Atmospheric Re-Entry

Study on Radio Frequency Communication Blackout Environments for a Small Deep Space Probe During an Atmospheric Re-entry 著者 Bendoukha Sidi Ahmed その他のタイトル 大気圏再突入時における超小型宇宙機の電波通信ブ ラックアウト環境に関する研究 学位授与年度 平成29年度 学位授与番号 17104甲工第446号 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10228/00006705 STUDY ON RADIO FREQUENCY COMMUNICATION BLACKOUT ENVIRONMENTS FOR A SMALL DEEP SPACE PROBE DURING AN ATMOSPHERIC RE-ENTRY By Sidi Ahmed BENDOUKHA Applied Sciences for Integrated System Engineering Laboratory of Spacecraft Environment Interaction Engineering Kyushu Institute of Technology This dissertation is submitted for the degree PhD in Engineering 09/2014 _ 09/ 2017 Doctoral Committee: Prof. Okuyama Kei-ichi (Main Advisor) Prof. Cho Mengu Prof. Toyoda Kazuhiro Prof. Akahoshi Yasuhiro Prof. Kenichi Asami “Success is not final, failure is not fatal: It is the courage to continue that counts.” By - Winston S. Churchill - Sidi Ahmed BENDOUKHA All Rights Reserved © 2017 DEDICATION To my beautiful spouse. IMENE, And My son. ANAS, Without their support, no one of this labours would have been possible ii AKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation and thanks to my supervisor Professor KEI- ICHI OKUYAMA, you have been a tremendous mentor for me. I would like to thank you for encouraging my research and for allowing me to grow as a research scientist. Your advice on both research as well as on my career have been priceless. I would also like to thank my committee members, Professor CHO MENGU, Professor TOYODA KAZUHIRO, Professor AKAHOSHI YASUHIRO, and Professor KENECHI ASAMI for serving as my committee members even at hardship. I also want to thank you for letting my mid-term evaluation and final defence be an enjoyable moment, and for your brilliant comments and suggestions, thanks so much to you. -

GEMINI PROGRAM MISSION PLANNING REPORT (U)

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19730073399 2018-11-20T16:58:36+00:00Z 120 NASA PROGRAM GEMINI WORKING PAPER NO. 5019 GEMINI PROGRAM MISSION PLANNING REPORT (u) DISTRIBUTION AND REFERENCING or referencing. correspondence and NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION MANNED SPACECRAFT CENTER Houston, Texas Tanna TO ft 10CK ^BIS MATERIAL CONTAINS INFORMATION AE Ud.nud.ry o, laoO TH^I^JUONAL DEFENSE OF THE u,pi*ff .........r, iHia iiiinflir" "- TH&^^ON^E LAWS, TITI F IB. n. s c. ^LiLTIllHi^ae^AND 794. THE TRANS- 173-76978. T Dnclas 00/99 07756 NASA PROGRAM GEMINI WORKING PAPER NO. 5019 GEMINI PROGRAM MISSION PLANNING REPORT Prepared By: Mission Planning Office Approved By: 'Willis Bf-Mitchell. Manager, Vehicles and Missions Authorized For Distribution By: Charles W. Mathews Manager, Gemini Program NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION MANNED SPACECRAFT CENTER HOUSTON, TEXAS January 6, 1965 •tiNCLASGiriCD 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1 General T"T"T~. .""." 7~~7 "TTTTT .' . "''.' .'."l-T^ 1.2 Document Revisions 1-1 1.3 Mission Planning Documents 1-1 2.0 GEMINI PROGRAM OBJECTIVES 2-1 J.O GEMINI MISSIONS 3-1 3.1 Gemini Mission One (GT-l) 3-1 3.2 Gemini Mission Two (GT-2) 3-2 3.3 Gemini Mission Three (GT-3) 3-3 3.4 Gemini Mission Four (GT-4) 3-5 3-5 Gemini Mission Five (GT-5) 3-6 3-6 Gemini-Agena Mission Six (GTA-6) 3-7 3-7 Gemini Mission Seven (GT-7) 3-9 3.8 Gemini-Agena Mission Eight (GTA-8) 3-10 3-9 Gemini-Agena Mission Nine (GTA-9) 3-11 3.10 Gemini-Agena Mission Ten (GTA-10) 3-12 3.11 Gemini-Agena Mission Eleven (GTA-ll) 3-13 3.12 Gemini-Agena Mission Twelve (GTA-12) 3-13 4. -

Solar Warning Architecture for Manned Missions to Mars James S

Air Force Institute of Technology AFIT Scholar Theses and Dissertations Student Graduate Works 6-16-2011 Solar Warning Architecture for Manned Missions to Mars James S. Bohren John K. Howard Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.afit.edu/etd Part of the Systems Engineering and Multidisciplinary Design Optimization Commons Recommended Citation Bohren, James S. and Howard, John K., "Solar Warning Architecture for Manned Missions to Mars" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 1305. https://scholar.afit.edu/etd/1305 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Graduate Works at AFIT Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AFIT Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOLAR WARNING ARCHITECTURE FOR MANNED MISSIONS TO MARS THESIS James S. Bohren John K. Howard Major, USAF Major USAF AFIT/GSE/ENV/11-J01DL DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Wright-Patterson Air Force base, Ohio APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRUBITION UNLIMITED The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the United States Government. This material is declared a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. AFIT/GSE/ENV/11-J01DL SOLAR WARNING ARCHITECTURE FOR MANNED MISSIONS TO MARS THESIS Presented to the faculty Department of Systems and Engineering Management Graduate School of Engineering and Management Air University Air Education and Training Command In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Systems Engineering James S. -

September 2017'S Geoeffective Space Weather and Impacts to Caribbean

Space Weather RESEARCH ARTICLE September 2017’s Geoeffective Space Weather and Impacts 10.1029/2018SW001897 to Caribbean Radio Communications During Special Section: Hurricane Response Space Weather Events of 4-10 September 2017 R. J. Redmon1 , D. B. Seaton1,2 , R. Steenburgh3,J.He4 , and J. V. Rodriguez1,2 1National Centers for Environmental Information, NOAA, Boulder, CO, USA, 2Cooperative Institute for Research in Key Points: Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA, 3Space Weather Prediction Center, NOAA, • The September 2017 solar events 4 impacted high-frequency radio Boulder, CO, USA, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute Joint Program in links for ground and aviation Oceanography and Applied Ocean Science and Engineering, Cambridge, MA, USA communication • Radio communications used in hurricane emergency and disaster Abstract Between 4 and 10 September 2017, multiple solar eruptions occurred from active region relief management were affected, AR12673. NOAA’s and NASA’s well-instrumented spacecraft observed the evolution of these geoeffective especially in the Caribbean • Active region AR12673 released four events from their solar origins, through the interplanetary medium, to their geospace impacts. The 6 X-class flares, three coronal mass September X9.3 flare was the largest to date for the nearly concluded solar cycle 24 and, in fact, the brightest ejections, and a solar energetic recorded since an X17 flare in September 2005, which occurred during the declining phase of solar cycle 23. particle event with ground level enhancement Rapid ionization of the sunlit upper atmosphere occurred, disrupting high-frequency communications in the Caribbean region while emergency managers were scrambling to provide critical recovery services caused by the region’s devastating hurricanes. -

Apollo 11 Mission Report November 1969

=-·. MSC-00171 NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION APOLLO 11 MISOS[ON REPORT I \ :Jj\ MANNED SPACECRAFT CENTER HOUSTON,TEXAS NOVEMBER 1969 APOLLO SPACECRAFT FLIGHT HISTORY Mission S12acecraft Description Launch date Launch site PA-l BP-6 First pad abort Nov. 7, 1963 White Sands Missile Range, N. Mex. A-001 BP-12 Transonic abort Ma;y 13, 1964 White Sands Missile Range, � N. Mex. 1- AS-101 BP-13 Nominal launch and Ma;y 28, 1964 Cape Kennedy, . - exit environment Fla. !' AS-102 BP-15 Nominal launch and Sept. 18, 1964 Cape Kennedy, exit environment Fla. A-002 BP-23 MaximUIIl dynamic Dec. 8, 1964 White Sands pressure abort Missile Range, --� \._._ -::_, N. Mex. AS-103 BP-16 Micrometeoroid Feb. 16, 1965 Cape Kennedy, experiment Fla. A-003 BP-22 Low-altitude abort Ma;y 19, 1965 White Sands (planned high- Missile Range, altitude abort) N. Mex. AS-104 BP-26 Micrometeoroid Ma;y 25 , 1965 Cape Kennedy, experiment and Fla • ..;;__ service module RCS launch environment PA-2 BP-23A Second pad abort June 29, 1965 White Sands Missile Range, N. Mex. AS-105 BP-9A Micrometeoroid July 30, 1965 Cape Kennedy, experiment and Fla. service module RCS launch environment -, A-004 SC-002 Power-on tumbling Jan. 20, 1966 White Sands boundary abort Missile Range, N. Mex. AS-201 SC-009 Supercircular Feb. 26, 1966 Cape Kennedy, entry with high Fla. heat rate AS-202 SC-Oll Supercircular Aug. 25, 1966 Cape Kennedy, \ entry with high Fla. heat load (Continued inside back cover) MSC-00171 APOLLO 11 MISSION REPORT PREPARED BY Mi ssion Evaluat ion Team / APPROVED BY George� M. -

Omond House Lunar Base Camp

Omond House Lunar Base Camp Team Name: T he Fighting Mongooses Team Members: Pablo Anguiano, Andrew Jones, Nathan McCanna, Jessica Pronga, Matthew Sconzo, Rohan Sikdar, Kieran Smith, Jack Sparkman, and Hannah Rens Faculty Advisor: Adam Nokes The University of Texas at Austin Department of Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics 1 The Fighting Mongooses Design Team Member List Member AIAA# & Signature Member AIAA# & Signature 1109098 1108615 Andrew Jones Nathan McCanna 1109097 951064 Rohan Sikdar Hannah Rens 833650 1109101 Jessica Pronga Jack Sparkman 1109099 936129 Pablo Anguiano Kieran Smith 998788 Matthew Sconzo Faculty Advisor: Adam Nokes 2 Table of Contents List of Acronyms 5 List of Figures 7 List of Tables 8 1. Executive Summary 9 2. Mission Description 13 3. Location and Sc ientific Operations 15 3.1. L unar Environment 15 3.2. B ase Camp Location 17 3.3. S cientific Operations 20 4. Habitat 23 5. Life Support 32 5.1. R adiation 32 5.2. R egenerative Life Support 37 5.3. Waste Management System 38 5.4. Water Recovery System 40 5.5. Air Revitalization System 43 5.6. Life Support Mass Flow Rates 46 5.7. Atmospheric Controls 48 5.8. Thermal Controls 50 5.9. Food 51 5.10. Medical 51 5.11. Psychology 53 6. Power 57 6.1. Power Requirements 57 6.2. Trade Studies and Decision Matrices 58 6.3. Power System Design 61 6.4. Extensibility 68 6.5. Mass, Volume, Area, and Lifetime Estimates 70 7. Communications 71 7.1. C ommunications Relay Satellite 71 7.2. L aser Communication Equipment 73 7.3. -

Tracking Solar Flares Using the Super SID Monitor

American Scientific Research Journal for Engineering, Technology, and Sciences (ASRJETS) ISSN (Print) 2313-4410, ISSN (Online) 2313-4402 © Global Society of Scientific Research and Researchers http://asrjetsjournal.org/ Tracking Solar Flares Using the Super SID Monitor K.A.J Gbadegesina*, Gbenga Adesunlorob a,b Physics Unit, Department of Science Technology, Federal Polytechnic, P.M.B. 5351, Ado-Ekiti, 360001, Nigeria aEmail: [email protected] bEmail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Sudden Ionospheric Disturbances are the immediate effects of solar flares, which impact the earth, and affect the upper atmospheric layers used for telecommunications. The aim of this project was to research, design and build a super sudden Ionospheric Disturbance Monitor for amplitude and phase perturbations occurring in the D-layer of the Ionosphere. For the design and implementation of this monitor Stanford University (NASA) and Society for Amateur Radio Astronomers (SARA) provided the SuperSID distribution pre-Amp, antenna wire and a RG 58 Coax Cable. During the design phase of the super SID Monitor a vertical loop antenna with dimension was constructed as a means to transfer energy from free space into a guided wave into the receiver; a VLF receiver from SARA was attached with the kit, which would incorporate all the signal processing and finally a data- logging device/software to act as an interface between the analogue natural events and the digital interface to record data to a PC. At the implementation stage the constructed balanced loop antenna was tested for its applicability with VLF receiver to process the signals from distant transmitters as a means to observe the propagation of the transmitted VLF signals received by the system.