Alien Encounters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society

I I. L /; I; COLLECTIONS OF THE j^olja Scotia ^isitoncal ^otitiv ''Out of monuments, names, wordes, proverbs, traditions, private records, and evidences, fragments of stories, passages of bookes, and the like, we do save, and recover somewhat from the deluge of time."—Lord Bacon: The Advancement of Learning. "A wise nation preserves its records, gathers up its muniments, decorates the tombs' of its illustrious dead, repairs its great structures, and fosters national pride and love of country, by perpetual re- ferences to the sacrifices and glories of the past."—Joseph Howe. VOLUME XVII. HALIFAX, N. S. Wm. Macnab & Son, 1913. FI034 Cef. 1 'TAe care which a nation devotes to the preservation of the monuments of its past may serve as a true measure of the degree of civilization to which it has attained.'' {Les Archives Principales de Moscou du Ministere des Affairs Etrangeres Moscow, 1898, p. 3.) 'To discover and rescue from the unsparing hand of time the records which yet remain of the earliest history of Canada. To preserve while in our power, such documents as may he found amid the dust of yet unexplored depositories, and which may prove important to general history, and to the particular history of this province.'" — Quebec Literary and Historical Society. NATIONAL MONUMENTS. (By Henry Van Dyke). Count not the cost of honour to the deadl The tribute that a mighty nation pays To those who loved her well in former days Means more than gratitude glory fled for ; For every noble man that she hath bred, Immortalized by art's immortal praise, Lives in the bronze and marble that we raise, To lead our sons as he our fathers led. -

Application for Gibraltarian Status (Section 9)

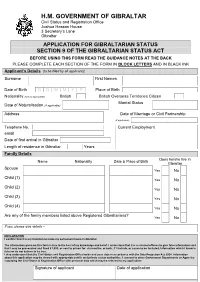

H.M. GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR Civil Status and Registration Office Joshua Hassan House 3 Secretary’s Lane Gibraltar APPLICATION FOR GIBRALTARIAN STATUS SECTION 9 OF THE GIBRALTARIAN STATUS ACT BEFORE USING THIS FORM READ THE GUIDANCE NOTES AT THE BACK PLEASE COMPLETE EACH SECTION OF THE FORM IN BLOCK LETTERS AND IN BLACK INK Applicant’s Details (to be filled by all applicants) Surname First Names Date of Birth D D M M Y Y Place of Birth Nationality (tick as appropriate) British British Overseas Territories Citizen Marital Status Date of Naturalisation (if applicable) Address Date of Marriage or Civil Partnership (if applicable) Telephone No. Current Employment email Date of first arrival in Gibraltar Length of residence in Gibraltar Years Family Details Does he/she live in Name Nationality Date & Place of Birth Gibraltar Spouse Yes No Child (1) Yes No Child (2) Yes No Child (3) Yes No Child (4) Yes No Are any of the family members listed above Registered Gibraltarians? Yes No If yes, please give details – DECLARATION I confirm that it is my intention to make my permanent home in Gibraltar. The information given on this form is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. I understand that it is a criminal offence to give false information and that I may be prosecuted and fined £1,000, or sent to prison for six months, or both, if I include, or cause to be included, information which I know is false or do not believe to be true. I also understand that the Civil Status and Registration Office holds and uses data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2004. -

Tmgm1de3.Pdf

Melissa G. Moyer ANALYSIS OF CODE-SWITCHING IN GIBRALTAR Tesi doctoral dirigida per la Dra. Aránzazu Usandizaga Departament de Filologia Anglesa i de Germanística Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 1992 To Jesús, Carol, and Robert ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The ¡dea of studying Gibraltar was first suggested to me by José Manuel Blecua in 1987 when I returned from completing a master's degree in Linguistics at Stanford University. The summer of that year I went back to California and after extensive library searches on language and Gibraltar, I discovered that little was known about the linguistic situation on "The Rock". The topic at that point had turned into a challenge for me. I immediately became impatient to find out whether it was really true that Gibraltarians spoke "a funny kind of English" with an Andalusian accent. It was José Manuel Blecua's excellent foresight and his helpful guidance throughout all stages of the fieldwork, writing, and revision that has made this dissertation possible. Another person without whom this dissertation would not have been completed is Aránzazu (Arancha) Usandizaga. As the official director she has pressured me when I've needed pressure, but she has also known when to adopt the role of a patient adviser. Her support and encouragement are much appreciated. I am also grateful to the English Department at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona chaired by Aránzazu Usandizaga and Andrew Monnickendam who granted me several short leaves from my teaching obligations in order to carry out the fieldwork on which this research is based. The rest of the English Department gang has provided support and shown their concern at all stages. -

An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar

.............................................................................................................................................................................................................WORK IN PROGESS WORK IN PROGRESS TOMASZ PACIORKOWSKI DOI: 10.15290/CR.2018.23.4.05 Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar Abstract. Gibraltar, popularly known as “The Rock”, has been a British overseas territory since the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1713. The demographics of this unique colony reflect its turbulent past, with most of the population being of Spanish, Portuguese or Italian origin (Garcia 1994). Additionally, there are prominent minorities of Indians, Maltese, Moroccans and Jews, who have also continued to influence both the culture and the languages spoken in Gibraltar (Kellermann 2001). Despite its status as the only English overseas territory in continental Europe, Gibraltar has so far remained relatively neglected by scholars of sociolinguistics, new dialect formation, and World Englishes. The paper provides a summary of the current state of sociolinguistic research in Gibraltar, focusing on such aspects as identity formation, code-switching, language awareness, language attitudes, and norms. It also delineates a plan for further research on code-switching and national identity following the 2016 Brexit referendum. Keywords: Gibraltar, code-switching, sociolinguistics, New Englishes, dialect formation, Brexit. 1. Introduction Gibraltar is located on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula and measures just about 6 square kilometres. This small size, however, belies an extraordinarily complex political history and social fabric. In the Brexit referendum of 23rd of June 2016, the inhabitants of Gibraltar overwhelmingly expressed their willingness to continue belonging to the European Union, yet at the moment it appears that they will be forced to follow the decision of the British govern- ment and leave the EU (Garcia 2016). -

Gibraltar's Constitutional Future

RESEARCH PAPER 02/37 Gibraltar’s Constitutional 22 MAY 2002 Future “Our aims remain to agree proposals covering all outstanding issues, including those of co-operation and sovereignty. The guiding principle of those proposals is to build a secure, stable and prosperous future for Gibraltar and a modern sustainable status consistent with British and Spanish membership of the European Union and NATO. The proposals will rest on four important pillars: safeguarding Gibraltar's way of life; measures of practical co-operation underpinned by economic assistance to secure normalisation of relations with Spain and the EU; extended self-government; and sovereignty”. Peter Hain, HC Deb, 31 January 2002, c.137WH. In July 2001 the British and Spanish Governments embarked on a new round of negotiations under the auspices of the Brussels Process to resolve the sovereignty dispute over Gibraltar. They aim to reach agreement on all unresolved issues by the summer of 2002. The results will be put to a referendum in Gibraltar. The Government of Gibraltar has objected to the process and has rejected any arrangement involving shared sovereignty between Britain and Spain. Gibraltar is pressing for the right of self-determination with regard to its constitutional future. The Brussels Process covers a wide range of topics for discussion. This paper looks primarily at the sovereignty debate. It also considers how the Gibraltar issue has been dealt with at the United Nations. Vaughne Miller INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS AND DEFENCE SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: List of 15 most recent RPs 02/22 Social Indicators 10.04.02 02/23 The Patents Act 1977 (Amendment) (No. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 18 March 2009

United Nations A/AC.109/2009/15 General Assembly Distr.: General 18 March 2009 Original: English Special Committee on the Situation with regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples Gibraltar Working paper prepared by the Secretariat Contents Page I. General ....................................................................... 3 II. Constitutional, legal and political issues ............................................ 3 III. Budget ....................................................................... 5 IV. Economic conditions ............................................................ 5 A. General................................................................... 5 B. Trade .................................................................... 6 C. Banking and financial services ............................................... 6 D. Transportation, communications and utilities .................................... 7 E. Tourism .................................................................. 8 V. Social conditions ............................................................... 8 A. Labour ................................................................... 8 B. Human rights .............................................................. 9 C. Social security and welfare .................................................. 9 D. Public health .............................................................. 9 E. Education ................................................................ -

Constitution and Government 33

CONSTITUTION AND GOVERNMENT 33 GOVERNORS GENERAL OF CANADA. FRENCH. FKENCH. 1534. Jacques Cartier, Captain General. 1663. Chevalier de Saffray de Mesy. 1540. Jean Francois de la Roque, Sieur de 1665. Marquis de Tracy. (6) Roberval. 1665. Chevalier de Courcelles. 1598. Marquis de la Roche. 1672. Comte de Frontenac. 1600. Capitaine de Chauvin (Acting). 1682. Sieur de la Barre. 1603. Commandeur de Chastes. 1685. Marquis de Denonville. 1607. Pierredu Guast de Monts, Lt.-General. 1689. Comte de Frontenac. 1608. Comte de Soissons, 1st Viceroy. 1699. Chevalier de Callieres. 1612. Samuel de Champlain, Lt.-General. 1703. Marquis de Vaudreuil. 1633. ii ii 1st Gov. Gen'l. (a) 1714-16. Comte de Ramesay (Acting). 1635. Marc Antoine de Bras de fer de 1716. Marquis de Vaudreuil. Chateaufort (Administrator). 1725. Baron (1st) de Longueuil (Acting).. 1636. Chevalier de Montmagny. 1726. Marquis de Beauharnois. 1648. Chevalier d'Ailleboust de Coulonge. 1747. Comte de la Galissoniere. (c) 1651. Jean de Lauzon. 1749. Marquis de la Jonquiere. 1656. Charles de Lauzon-Charny (Admr.) 1752. Baron (2nd) de Longueuil. 1657. D'Ailleboust de Coulonge. 1752. Marquis Duquesne-de-Menneville. 1658. Vicomte de Voyer d'Argenson. j 1755. Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal. 1661. Baron Dubois d'Avaugour. ! ENGLISH. ENGLISH. 1760. General Jeffrey Amherst, (d) 1 1820. James Monk (Admin'r). 1764. General James Murray. | 1820. Sir Peregrine Maitland (Admin'r). 1766. P. E. Irving (Admin'r Acting). 1820. Earl of Dalhousie. 1766. Guy Carleton (Lt.-Gov. Acting). 1824. Lt.-Gov. Sir F. N. Burton (Admin'r). 1768. Guy Carleton. (e) 1828. Sir James Kempt (Admin'r). 1770. Lt.-Gov. -

Gibraltar-Messenger.Net

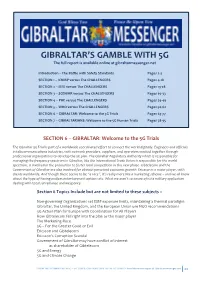

GIBRALTAR’S GAMBLE WITH 5G The full report is available online at gibraltarmessenger.net Introduction – The Battle with Safety Standards Pages 2-3 SECTION 1 – ICNIRP versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 4-18 SECTION 2 – IEEE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 19-28 SECTION 3 – SCENIHR versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 29-33 SECTION 4 – PHE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 34-49 SECTION 5 – WHO versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 50-62 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials Pages 63-77 SECTION 7 – GIBRALTARIANS: Welcome to the 5G Human Trials Pages 78-95 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials The Gibraltar 5G Trial is part of a worldwide coordinated effort to connect the world digitally. Engineers and officials in telecommunications industries, with network providers, suppliers, and operators worked together through professional organizations to develop the 5G plan. The Gibraltar Regulatory Authority which is responsible for managing the frequency spectrum in Gibraltar, like the International Trade Union is responsible for the world spectrum, is involved in the promotion to foster local competition in this new phase. Gibtelecom and the Government of Gibraltar are also involved for obvious perceived economic growth. Ericsson is a major player, with clients worldwide. And though there seems to be “a race”, it’s really more like a marketing scheme – and we all know about the hype of having endless entertainment options etc. What we aren’t so aware of is its military application dealing with total surveillance and weaponry. Section 6 Topics Include but -

Innovation Edition

1 Issue 36 - Summer 2019 iMindingntouch Gibraltar’s Business INNOVATION EDITION INSIDE: Hungry Monkey - Is your workplace The GFSB From zero to home inspiring Gibtelecom screen hero innovation & Innovation creativity? Awards 2019 intouch | ISSUEwww.gfsb.gi 36 | SUMMER 2019 www.gibraltarlawyers.com ISOLAS Trusted Since 1892 Property • Family • Corporate & Commercial • Taxation • Litigation • Trusts Wills & Probate • Shipping • Private Client • Wealth management • Sports law & management For further information contact: [email protected] ISOLAS LLP Portland House Glacis Road PO Box 204 Gibraltar. Tel: +350 2000 1892 Celebrating 125 years of ISOLAS CONTENTS 3 05 MEET THE BOARD 06 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD 08 HUNGRY MONKEY - FROM ZERO TO HOME SCREEN HERO 12 WHAT’S THE BIG iDEA? 14 IS YOUR WORKPLACE INSPIRING INNOVATION & CREATIVITY? 12 16 NETWORKING, ONE OF THE MAIN REASONS PEOPLE JOIN THE GFSB WHAT’S THE BIG IDEA? 18 SAVE TIME AND MONEY WITH DESKTOPS AND MEETINGS BACKED BY GOOGLE CLOUD 20 NOMNOMS: THE NEW KID ON THE DELIVERY BLOCK 24 “IT’S NOT ALL ABOUT BITCOIN”: CRYPTOCURRENCY AND DISTRIBUTED LEDGER TECHNOLOGY 26 JOINT BREAKFAST CLUB WITH THE WOMEN IN BUSINESS 16 26 NETWORKING, ONE OF THE JOINT BREAKFAST CLUB WITH 28 GFSB ANNUAL GALA DINNER 2019 MAIN REASONS PEOPLE JOIN THE WOMEN IN BUSINESS THE GFSB 32 MEET THE GIBRALTAR BUSINESS WITH A TRICK UP ITS SLEEVE 34 SHIELDMAIDENS VIRTUAL ASSISTANTS - INDEFATIGABLE ASSISTANCE AND SUPPORT FOR ALL BUSINESSES 36 ROCK RADIO REFRESHES THE AIRWAVES OVER GIBRALTAR 38 WHEN WHAT YOU NEED, NEEDS TO HAPPEN RIGHT -

Download Guide

#VISITGIBRALTAR GIBRALTAR WHAT TO SEE & DO ST MICHAEL’S CAVE & LOWER ST THE WINDSOR BRIDGE MICHAEL’S CAVE This tourist attraction is definitely not This beautiful natural grotto was prepared as for the faint-hearted, but more intrepid a hospital during WWII; today it is a unique residents and visitors can visit the new auditorium. There is also a lower segment that suspension bridge at Royal Anglian Way. provides the most adventurous visitor with an This spectacular feat of engineering is experience never to be forgotten, however, 71metres in length, across a 50-metre-deep these tours need to be pre-arranged. gorge. Gibraltar Nature Reserve, Upper Rock Nature Reserve, Gibraltar APES’ DEN WORLD WAR II TUNNELS One of Gibraltar’s most important tourist During WWII an attack on Gibraltar was attractions, the Barbary Macaques are imminent. The answer was to construct a actually tailless monkeys. We recommend massive network of tunnels in order to build that you do not carry any visible signs of food a fortress inside a fortress. or touch these animals as they may bite. GREAT SIEGE TUNNELS 9.2” GUN, O’HARA’S BATTERY The Great Siege Tunnels are an impressive Located at the highest point of the Rock, defence system devised by military engineers. O’Hara’s Battery houses a 9.2” gun with Excavated during the Great Siege of 1779-83, original WWII material on display and a film these tunnels were hewn into the rock with from 1947 is also on show. the aid of the simplest of tools and gunpowder. Gibraltar Nature Reserve, Upper Rock Nature Reserve, Gibraltar THE SKYWALK THE MOORISH CASTLE Standing 340 metres directly above sea level, The superbly conserved Moorish Castle is the Skywalk is located higher than the tallest part of the architectural legacy of Gibraltar’s point of The Shard in London. -

Accounts of the Gibraltar Culture and Heritage Agency for the Period Ended 31 March 2012 TABLE of CONTENTS Page No

Gibraltar Audit Office Certificate of the Principal Auditor on the Accounts of the Gibraltar Culture and Heritage Agency for the period ended 31 March 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Audit Certificate I Accounts 1 Gibraltar Audit Office THE CERTIFICATE OF THE PRINCIPAL AUDITOR TO THE PARLIAMENT I certify that I have audited the financial statements of the Gibraltar Culture and Heritage Agency for the financial period 8 September 2011 to 31 March 2012 in accordance with the ·provisions of Section 14(2) of the repealed Gibraltar Culture and Heritage Agency Act 2011. These statements comprise the Receipts and Payments Account, the Capital Account and the Balance Sheet. These financial statements have been prepared using the cash receipts and disbursements basis of accounting. Respective responsibilities of the Gibraltar Culture and Heritage Agency and the Principal Auditor The Gibraltar Culture and Heritage Agency is responsible for the preparation of the financial statements and for being satisfied that they are properly presented. The policy is to prepare the financial statements on the cash receipts and disbursements basis. On this basis revenue is recognised when received rather than when earned, and expenses are recognised when paid rather than when incurred. My responsibility is to audit, certify and report on the financial statements in accordance with the provisions of Sections 14(2) and (3) of the repealed Gibraltar Culture and Heritage Agency Act 2011. I conducted my audit of the financial statements in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Scope of the audit of the financial statements An audit involves obtaining evidence about the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements sufficient to give reasonable assurance that the financial statements are free from material misstatement, whether caused by fraud or error. -

OC 1 to OC 10 Online Statistics

Table OC.8 Official Car Usage by the Minister for Sports, Culture, Heritage and Youth, since 9 December 2011 Purpose of use Date Residence to Victoria Stadium - GFA football match 08 January 2012 Residence to La Linea, Palacio de Congresos - Real Balonpedicas Anniversary 19 January 2012 Residence to Central Hall - 100th anniversary of St Joseph's FC 21 January 2012 Ministry of Culture to - Site meeting Upper Rock 01 February 2012 Residence to Ocean Village - GBC Sports Award 08 February 2012 Residence Tercentenary Hall, Boxing 09 February 2012 Ministry of Culture to GibDock - Press call 09 February 2012 Residence to City Fire Brigade & Central Hall (trophies) 16 February 2012 Ministry of Culture to Bleak House Presentation of Certificates to AquaGib employees 21 February 2012 Ministry of Culture to Youth Clubs visit 06 March 2012 Residence to Ince's Hall - Gala night / Drama Festival 17 March 2012 Ministry of Culture to visit to Retreat Centre and Flat Bastion Magazine 27 March 2012 Residence to dinner at Caleta Hotel - Gibraltar International Rugby 28 March 2012 Residence to El Patio/Rock Hotel - Miss Gibraltar dinner 12 April 2012 Ministry of Culture to GJBS visit followed by visit to airport terminal 13 April 2012 Residence to Miss Gibraltar show at St Michael's Cave 14 April 2012 Residence to Gibraltar fashion week party at The Mount 19 April 2012 Residence to Malaga airport - Little Constalation Art Workshop in Genoa Italy 26 April 2012 Malaga airport to Gibraltar - Little Constalation Art Workshop in Genoa Italy 30 April 2012 Ministry