The Institutionalisation of Children and British Colonisation in New South Wales, 1750-1828

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nineteenth Century Court Records

Nineteenth Century Court Records Subject Court Year Isaac H. Aldrich vs. Joseph B. Mackin & John Webb Supreme Court 1850 Jacob Smith vs. Jabez Felt et al Supreme Court 1852 Elizabeth Hinckley vs. Robert Porter & Nelson Clark Supreme Court 1852 John Steward Jr. vs Solon Peck et al Supreme Court 1852 Masterton Ure, et al vs. Allen S. Benson Supreme Court 1852 Hooper C. Prouty vs. Albany Schnectady RR Co. Supreme Court 1852 Erastus Crandall vs. John Van Allen et al Supreme Court 1853 Miranda Page vs. Marietta Peck et al Supreme Court 1853 Mary Smith et al vs. Electa Willett et al Supreme Court 1853 George W. Smith vs. William G. Wells Supreme Court 1853 John C. Strong vs. Aaron Lucas &J ohn S. Prouty Supreme Court 1853 Elijah Gregory vs. Alanson & Arnold Watkins Supreme Court 1853 George A. Gardner vs. Leman Garlinghouse Supreme Court 1853 John N. Whiting vs. Gideon D. Baggerly Supreme Court 1854 George Snyder vs. Selah Dickerson Supreme Court 1854 Hazaard A. Potter vs. John D. Stewart & Nelson Tunnicliffe Supreme Court 1854 William J. Lewis vs. Stephen Trickey Supreme Court 1855 Charles Webb vs. Henry Overman & Algernon Baxter Supreme Court 1855 Marvin Power vs. Jacob Ferguson Supreme Court 1855 Daniel Phelps vs. Clark Marlin et al Supreme Court 1855 Phinehas Prouty vs. David Barron et al Supreme Court 1855 John C. Lyon vs. Asahel & Sarah Gooding Supreme Court 1855 Frances Sutherland vs. Elizabeth Bannister Supreme Court 1855 Persis Baker for Jasper G. Baker, deceased Supreme Court 1855 Aaron Parmelee & David Wiggins vs. Selleck Dann Supreme Court 1855 Milo M. -

Phanfare May/June 2006

Number 218 – May-June 2006 Observing History – Historians Observing PHANFARE No 218 – May-June 2006 1 Phanfare is the newsletter of the Professional Historians Association (NSW) Inc and a public forum for Professional History Published six times a year Annual subscription Email $20 Hardcopy $38.50 Articles, reviews, commentaries, letters and notices are welcome. Copy should be received by 6th of the first month of each issue (or telephone for late copy) Please email copy or supply on disk with hard copy attached. Contact Phanfare GPO Box 2437 Sydney 2001 Enquiries Annette Salt, email [email protected] Phanfare 2005-06 is produced by the following editorial collectives: Jan-Feb & July-Aug: Roslyn Burge, Mark Dunn, Shirley Fitzgerald, Lisa Murray Mar-Apr & Sept-Oct: Rosemary Broomham, Rosemary Kerr, Christa Ludlow, Terri McCormack, Anne Smith May-June & Nov-Dec: Ruth Banfield, Cathy Dunn, Terry Kass, Katherine Knight, Carol Liston, Karen Schamberger Disclaimer Except for official announcements the Professional Historians Association (NSW) Inc accepts no responsibility for expressions of opinion contained in this publication. The views expressed in articles, commentaries and letters are the personal views and opinions of the authors. Copyright of this publication: PHA (NSW) Inc Copyright of articles and commentaries: the respective authors ISSN 0816-3774 PHA (NSW) contacts see Directory at back of issue PHANFARE No 218 – May-June 2006 2 Contents At the moment the executive is considering ways in which we can achieve this. We will be looking at recruiting more members and would welcome President’s Report 3 suggestions from members as to how this could be Archaeology in Parramatta 4 achieved. -

Winter 2012 SL

–Magazine for members Winter 2012 SL Olympic memories Transit of Venus Mysterious Audubon Wallis album Message Passages Permanence, immutability, authority tend to go with the ontents imposing buildings and rich collections of the State Library of NSW and its international peers, the world’s great Winter 2012 libraries, archives and museums. But that apparent stasis masks the voyages we host. 6 NEWS 26 PROVENANCE In those voyages, each visitor, each student, each scholar Elegance in exile Rare birds finds islets of information and builds archipelagos of Classic line-up 30 A LIVING COLLECTION understanding. Those discoveries are illustrated in this Reading hour issue with Paul Brunton on the transit of Venus, Richard Paul Brickhill’s Biography and Neville on the Wallis album, Tracy Bradford on our war of nerves business collections on Olympians such as Shane Gould and John 32 NEW ACQUISITIONS Konrads, and Daniel Parsa on Audubon’s Birds of America, Library takes on Vantage point one of our great treasures. Premier’s awards All are stories of passage, from Captain James Cook’s SL French connection Art of politics voyage of geographical and scientific discovery to Captain C THE MAGAZINE FOR STATE LIBRARY OF NSW BUILDING A STRONG ON THIS DAY 34 FOUNDATION MEMBERS, 8 James Wallis’s album that includes Joseph Lycett’s early MACQUARIE STREET FRIENDS AND VOLUNTEERS FOUNDATION Newcastle and Sydney watercolours. This artefact, which SYDNEY NSW 2000 IS PUBLISHED QUARTERLY 10 FEATURE New online story had found its way to a personal collection in Canada, BY THE LIBRARY COUNCIL PHONE (02) 9273 1414 OF NSW. -

Emeritus Professor Garth Ian Gaudry 16 May 1941 Π18 October 2012

Emeritus Professor Garth Ian Gaudry 16 May 1941 { 18 October 2012 Emeritus Professor Garth Gaudry died in Sydney on 18 October 2012 after a long battle with a brain tumour. Those of us in the mathematical community will remember him for different reasons; as research collaborators, as a friend, a teacher, lover of red wine, rugby, music and many other things. Above all he will be remembered for leadership in promoting mathematical sciences in the community and politically. Personal connections Garth was my friend and colleague who came into my life at the end of the 1980s. An early encounter involved a meeting in a Carlton coffee caf´e with Garth, David Widdup and me. David was Executive Director of the Federation of Australian Scientific and Technological Societies (FASTS) and a wonderful friend of mathematics. Garth was the inaugural President of the Australian Mathematical Sciences Council (AMSC) and I had just become secretary. Garth and David were discussing a press release with what I can only describe as happy enthusiasm. As the language of the press release became more and more colourful, I thought this is going to be an interesting time. So it proved to be. Early history Garth’s family history dates from the First Fleet. It is a fascinating story of which he was rightly proud and so I have reproduced part of a speech his wife Patricia gave at a dinner for his 70th birthday as an appendix. He was the son of a Queensland primary teacher and spent his first nine years in Rockhampton. His father then became head teacher at Tekowai outside of Mackay and Garth completed his secondary education at Mackay High School, riding his Obituary:GarthIanGaudry 43 bike five miles each way. -

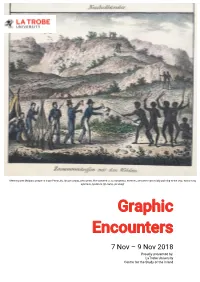

Graphic Encounters Conference Program

Meeting with Malgana people at Cape Peron, by Jacque Arago, who wrote, ‘the watched us as dangerous enemies, and were continually pointing to the ship, exclaiming, ayerkade, ayerkade (go away, go away)’. Graphic Encounters 7 Nov – 9 Nov 2018 Proudly presented by: LaTrobe University Centre for the Study of the Inland Program Melbourne University Forum Theatre Level 1 Arts West North Wing 153 148 Royal Parade Parkville Wednesday 7 November Program 09:30am Registrations 10:00am Welcome to Country by Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO 10:30am (dis)Regarding the Savages: a short history of published images of Tasmanian Aborigines Greg Lehman 11.30am Morning Tea 12.15pm ‘Aborigines of Australia under Civilization’, as seen in Colonial Australian Illustrated Newspapers: Reflections on an article written twenty years ago Peter Dowling News from the Colonies: Representations of Indigenous Australians in 19th century English illustrated magazines Vince Alessi Valuing the visual: the colonial print in a pseudoscientific British collection Mary McMahon 1.45pm Lunch 2.45pm Unsettling landscapes by Julie Gough Catherine De Lorenzo and Catherine Speck The 1818 Project: Reimagining Joseph Lycett’s colonial paintings in the 21st century Sarah Johnson Printmaking in a Post-Truth World: The Aboriginal Print Workshops of Cicada Press Michael Kempson 4.15pm Afternoon tea and close for day 1 2 Thursday 8 November Program 10:00am Australian Blind Spots: Understanding Images of Frontier Conflict Jane Lydon 11:00 Morning Tea 11:45am Ad Vivum: a way of being. Robert Neill -

Commander Ship Port Tons Mate Gunner Boatswain Carpenter Cook

www.1812privateers.org ©Michael Dun Commander Ship Port Tons Mate Gunner Boatswain Carpenter Cook Surgeon William Auld Dalmarnock Glasgow 315 John Auld Robert Miller Peter Johnston Donald Smith Robert Paton William McAlpin Robert McGeorge Diana Glasgow 305 John Dal ? Henry Moss William Long John Birch Henry Jukes William Morgan William Abrams Dunlop Glasgow 331 David Hogg John Williams John Simpson William James John Nelson - Duncan Grey Eclipse Glasgow 263 James Foulke Martin Lawrence Joseph Kelly John Kerr Robert Moss - John Barr Cumming Edward Glasgow 236 John Jenkins James Lee Richard Wiles Thomas Long James Anderson William Bridger Alexander Hardie Emperor Alexander Glasgow 327 John Jones William Jones John Thomas William Thomas James Williams James Thomas Thomas Pollock Lousia Glasgow 324 Alexander McLauren Robert Caldwell Solomon Piike John Duncan James Caldwell none John Bald Maria Glasgow 309 Charles Nelson James Cotton? John George Thomas Wood William Lamb Richard Smith James Bogg Monarch Glasgow 375 Archibald Stewart Thomas Boutfield William Dial Lachlan McLean Donald Docherty none George Bell Bellona Greenock 361 James Wise Thomas Jones Alexander Wigley Philip Johnson Richard Dixon Thomas Dacers Daniel McLarty Caesar Greenock 432 Mathew Simpson John Thomson William Wilson Archibald Stewart Donald McKechnie William Lee Thomas Boag Caledonia Greenock 623 Thomas Wills James Barnes Richard Lee George Hunt William Richards Charles Bailey William Atholl Defiance Greenock 346 James McCullum Francis Duffin John Senston Robert Beck -

Sailing of the First Fleet

1788 AD Magazine of the Fellowship of First Fleeters Inc. ACN 003 223 425 PATRON: Her Excellency, Professor Marie Bashir, AC, CVO, Governor of New South Wales Volume 44, Issue 4 45th Year of Publication August/September, 2013 To live on in the hearts and minds of Descendants is never to die SAILING OF THE FIRST FLEET - CELEBRATION LUNCH This year began a little differently for the Fellowship when probably all benefit by their running some workshops for us the usual Australia Day Luncheon had to be postponed due so we can master verse 2 off by heart. Like our ancestors, to the unavailability of the booked venue. A ‘those who’ve come across the seas’, albeit recently and disappointment it was, for sure, especially for those who ongoing, deserve to share our plains to keep our fair land had booked from afar to spend some time in Sydney for ‘renowned of all’. their summer holiday and join other First Fleeters at the Vice Patron Commodore Paul Kable, in saying ‘grace’, major get-together of the year. thanked the Lord for “our land and its bountiful provisions The Pullman Hotel in College St., Sydney had finished their made available to us through the endurance, motivation downstairs reservations by 11th May and so the celebratory and courage of our First Fleet ancestors.” The Loyal Toast gathering proceeded accordingly. With a change of title in followed, led by Director Robin Palmer, and the President keeping with the date, 226 years, almost to the day since then proposed the Toast to our First Fleet ancestors, listing the First Fleet sailed out of Portsmouth, the 78 names of those represented 139 guests sat down to enjoy a delicious Master of Ceremonies Roderick Best by the guests at the luncheon. -

Nyungar Tradition

Nyungar Tradition : glimpses of Aborigines of south-western Australia 1829-1914 by Lois Tilbrook Background notice about the digital version of this publication: Nyungar Tradition was published in 1983 and is no longer in print. In response to many requests, the AIATSIS Library has received permission to digitise and make it available on our website. This book is an invaluable source for the family and social history of the Nyungar people of south western Australia. In recognition of the book's importance, the Library has indexed this book comprehensively in its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Biographical Index (ABI). Nyungar Tradition by Lois Tilbrook is based on the South West Aboriginal Studies project (SWAS) - in which photographs have been assembled, not only from mission and government sources but also, importantly in Part ll, from the families. Though some of these are studio shots, many are amateur snapshots. The main purpose of the project was to link the photographs to the genealogical trees of several families in the area, including but not limited to Hansen, Adams, Garlett, Bennell and McGuire, enhancing their value as visual documents. The AIATSIS Library acknowledges there are varying opinions on the information in this book. An alternative higher resolution electronic version of this book (PDF, 45.5Mb) is available from the following link. Please note the very large file size. http://www1.aiatsis.gov.au/exhibitions/e_access/book/m0022954/m0022954_a.pdf Consult the following resources for more information: Search the Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Biographical Index (ABI) : ABI contains an extensive index of persons mentioned in Nyungar tradition. -

The Rise and Decline of Cannabis Prohibition the History of Cannabis in the UN Drug Control System and Options for Reform

TRANSNATIONAL I N S T I T U T E THE RISE AND DECLINE OF CANNABIS PROHIBITION THE HISTORY OF CANNABIS IN THE UN DruG CONTROL SYSTEM AND OPTIONS FOR REFORM 3 The Rise and Decline of Cannabis Prohibition Authors Dave Bewley-Taylor Tom Blickman Martin Jelsma Copy editor David Aronson Design Guido Jelsma www.guidojelsma.nl Photo credits Hash Marihuana & Hemp Museum, Amsterdam/ Barcelona Floris Leeuwenberg Pien Metaal UNOG Library/League of Nations Archives UN Photo Printing Jubels, Amsterdam Contact Transnational Institute (TNI) De Wittenstraat 25 1052 AK Amsterdam Netherlands Tel: +31-(0)20-6626608 Fax: +31-(0)20-6757176 [email protected] www.tni.org/drugs www.undrugcontrol.info www.druglawreform.info Global Drug Policy Observatory (GDPO) Research Institute for Arts and Humanities Rooms 201-202 James Callaghan Building Swansea University Financial contributions Singleton Park, Swansea SA2 8PP Tel: +44-(0)1792-604293 This report has been produced with the financial www.swansea.ac.uk/gdpo assistance of the Hash Marihuana & Hemp Museum, twitter: @gdpo_swan Amsterdam/Barcelona, the Open Society Foundations and the Drug Prevention and Information Programme This is an Open Access publication distributed under (DPIP) of the European Union. the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which of TNI and GDPO and can under no circumstances be permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction regarded as reflecting the position of the donors. in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. TNI would appreciate receiving a copy of the text in which this document is used or cited. -

The Illawarra Diary of Lady Jane Franklin, 10-17 May 1839

University of Wollongong Research Online Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Chancellor (Education) - Papers Chancellor (Education) 1-9-1988 The Illawarra Diary of Lady Jane Franklin, 10-17 May 1839 Michael K. Organ University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Organ, Michael K.: The Illawarra Diary of Lady Jane Franklin, 10-17 May 1839 1988. https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers/34 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Illawarra Diary of Lady Jane Franklin, 10-17 May 1839 Abstract Jane Franklin, the wife of Sir John Franklin, Governor of Tasmania, travelled overland from Port Phillip to Sydney in 1839. During the trip she kept detailed diary notes and wrote a number of letters. Between 10-17 May 1839 she journeyed to the Illawarra region on the coast of New South Wales. A transcription of the original diary notes is presented, along with descriptive introduction to the life and times of Jane Franklin. Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Social and Behavioral Sciences Publication Details This booklet was originally published as Organ, M (ed), The Illawarra Diary of Lady Jane Franklin, 10-17 May 1839, Illawarra Historical Publications, 1988, 51p. This book is available at Research Online: -

This Item Is Held in Loughborough University's Institutional Repository

This item is held in Loughborough University’s Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) and was harvested from the British Library’s EThOS service (http://www.ethos.bl.uk/). It is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ CAROLINE CHISHOLM 1808-1877 ORDINARY WOMAN - EXTRAORDINARY LIFE IMPOSSIBLE CATEGORY by Carole Ann Walker A Doctoral Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy of Loughborough University 2001 Supervisor: Dr. M. Pickering Department of Social Science © Carole Walker, 2001. ABSTRACT Caroline Chisholm Australia Nineteenth century emigration Nineteenth century women's history Philanthropy The purpose of this thesis is to look at the motivations behind the life and work of Caroline Chisholm, nee Jones, 1808-1877, and to ascertain why British historians have chosen to ignore her contribution to the nineteenth century emigration movement, while attending closely to such women as Nightingale for example. The Introduction to the thesis discusses the difficulties of writing a biography of a nineteenth century woman, who lived at the threshold of modernity, from the perspective of the twenty-first century, in the period identified as late modernity or postmodernity. The critical issues of writing a historical biography are explored. Chapter Two continues the debate in relation to the Sources, Methods and Problems that have been met with in writing the thesis. Chapters Three to Seven consider Chisholm's life and work in the more conventional narrative format, detailing where new evidence has been found. -

King to Camden. 681

KING TO CAMDEN. 681 [Enclosure E.] lg06 RETURN of Live Stock, March 8th-15th 1806. is March. [A copy of this return is not available.] HveUstock for use as STATEMENT of the time the Cattle belonging to the Crown in Provisions- New South Wales will last at whole and half Rations for the Numbers Victualled from the Stores, Say 2,000 full Rations at 7 lbs. of Fresh Meat a week each full Ration. 3 014 Cattle 300 lbs At full { ' ® - each ") 68 Weekg \ 1,410 Sheep @ 30 „ „ j b» weeks. At half j 3.0W Cattle @ 300 lbs. each ( 186 Weeks \ 1,410 Sheep @ 30 „ „ ) The whole Number of Cattle, Young and old being taken, they are averaged at 300 lbs. each; But the grown Cattle well fattened will weigh from 6 to 800 Weight. For the Cattle and other Stock belonging to Individuals, a Reference may be made to the last General Muster in August, 1805. [Enclosure F.] MR. JOHN MACARTHUR TO GOVERNOR KING. Sir, Parramatta, 2nd March, 1806. When I received my Grants of Land at the Cow Pastures, Macarthur's consequent on the Right Hon'ble Earl Camden's directions, Tour gJ'g^Hd cattle Excellency was pleased to signify, if a Proposal were to be made for reclaiming the numerous Herds of Wild Cattle on Terms equitable and of evident Advantage to Government, such a Pro posal might receive Your Approbation, and induce You to enter into a Contract for the Accomplishment of that Object. Having since very attentively reflected on the Practicability of such an Undertaking, I now do myself the honor to lay before You the enclosed Proposal, And I trust it will appear to Your Excellency both moderate and equitable, Altho' doubtless it will admit of, and perhaps require, some Modifications.