Bulfinch's Mythology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Journal Intime D'hercule D'andré Dubois La Chartre. Typologie Et Réception Contemporaine Du Mythe D'hercule

Commission de Programme en langues et lettres françaises et romanes Le Journal intime d’Hercule d’André Dubois La Chartre. Typologie et réception contemporaine du mythe d’Hercule Alice GILSOUL Mémoire présenté pour l’obtention du grade de Master en langues et lettres françaises et romanes, sous la direction de Mme. Erica DURANTE et de M. Paul-Augustin DEPROOST Louvain-la-Neuve Juin 2017 2 Le Journal intime d’Hercule d’André Dubois La Chartre. Typologie et réception contemporaine du mythe d’Hercule 3 « Les mythes […] attendent que nous les incarnions. Qu’un seul homme au monde réponde à leur appel, Et ils nous offrent leur sève intacte » (Albert Camus, L’Eté). 4 Remerciements Je tiens à remercier Madame la Professeure Erica Durante et Monsieur le Professeur Paul-Augustin Deproost d’avoir accepté de diriger ce travail. Je remercie Madame Erica Durante qui, par son écoute, son exigence, ses précieux conseils et ses remarques m’a accompagnée et guidée tout au long de l’élaboration de ce présent mémoire. Mais je me dois surtout de la remercier pour la grande disponibilité dont elle a fait preuve lors de la rédaction de ce travail, prête à m’aiguiller et à m’écouter entre deux taxis à New-York. Je remercie également Monsieur Paul-Augustin Deproost pour ses conseils pertinents et ses suggestions qui ont aidé à l’amélioration de ce travail. Je le remercie aussi pour les premières adresses bibliographiques qu’il m’a fournies et qui ont servi d’amorce à ma recherche. Mes remerciements s’adressent également à mes anciens professeurs, Monsieur Yves Marchal et Madame Marie-Christine Rombaux, pour leurs relectures minutieuses et leurs corrections orthographiques. -

Die Adaption Des Orlando Furioso Für Das Italienische Fernsehen Von Edoardo Sanguineti Und Luca Ronconi

https://doi.org/10.20378/irbo-51613 lucA FormiAni(Bamberg) Die Adaption des Orlando Furioso für das italienische Fernsehen von Edoardo Sanguineti und Luca Ronconi ErstEndeder60erJahrekamenderRegisseurundTheaterschauspieler LucaRonconiundderDramatiker,PoetundIntellektuelleEdoardoSangui- netiaufdieIdee,AriostsOrlando Furioso (aufDeutschDer rasende Roland) fürdasTheaterzuadaptieren.ÜberdiesesProjektverrietderRegisseurLuca RonconiderMailänderZeitungIl Corriere della sera1einigeTagevorder Premiere: L´Orlandosaràrappresentatoperinteroattraversounasommadiazionisimultaneecheavver- rannoinluoghilontanitraloro:ilpubblicodivisoingruppi,seguiràtrai„filoni“chenoipropo- niamoquellochepreferirà,quellogrottescooquelloerotico,quelloepicooquellofantastico. Ipercorsideglispettatorisarannodeterminatidaunascenografiamoltoarticolata,affidatanon aunsoloscenografo,maagliartisticheriteniamopiùadattiadesprimereciascunodeitemi rappresentati2. AndieserAussagekannmanbereitsdieneoavantgardistischenCharak- teristikadesTheaterserkennen,dievonEdoardoSanguinetischonimRah- mendesGruppo63formuliertwurden3:dasTheateralsneueForm,inderdas PublikummitdemSchauspielerinteragierenkannundgleichzeitigRegeln wiederfindet,dieesnichtalsTheaterregelnerkennt,sondernalsTeilseines eigenenLebens.DasechteTheateristnämlichjenes,welcheseineÜberwin- dungdeselitärenwiedespopulärenTheatersermöglicht4. DerVerfasserdesArtikelsimCorriere,GiulianoZingone,sahschonvo- raus,dassdieAufführungdesOrlando Furioso(=OF)derAuslöserfüreine ReihevonPolemikensowohlseitensderLiteratenalsauchderTheaterkriti- kerwerdenwürde. -

Thomas Hart Benton MS Text

Thomas Hart Benton: Painter of Everyday America Thomas Hart Benton was born in Missouri in 1889. Throughout his long life he made thousands of drawings and paintings. He was inspired by his experiences of America. As a boy his mother took Tom, his two sisters, and his brother to visit her family in Texas. He traveled with his father, who was running for US Congress. When his father won, the Bentons lived in Washington DC. They came home to Missouri in the summers, where young Tom had a pony, took care of a cow, and picked strawberries. Thomas Hart Benton, 1925, Self Portrait, oil on canvas Collection of the artist;‘s daughter, Jessie Benton Lyman. (It was on the cover of Time magazine, December 24, 1934 Tom's first job was as a newspaper artist in Joplin, Missouri. He studied art in Chicago, Illinois, then in Paris, and finally in New York, New York. During World War I, Benton served in the Navy in Norfolk, Virginia. He created camouflage paint designs for Navy ships. After the war, Benton returned to New York City where he taught art. There he met and married his wife, Rita. The Benton family lived most of the year in New York, and spent their summers on an island off Thomas Hart Benton, 1943, July Hay, egg tempera and oil on the coast of masonite, 38” x 26.7/8” Massachusetts. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The death of his father was a shock to Benton. He started to take long walks in the Catskill Mountains of New York. -

The Classical Tradition in America Saving Endangered Books Lynne Cheney Answers Tough Questions Editor's Notes

HumanitiesNATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES • VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 • JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1987 The Classical Tradition in America Saving Endangered Books Lynne Cheney Answers Tough Questions Editor's Notes A Legacy of Value The pediments, pillars, and domes of official Washington are architectural symbols of the influence of classical Greece and Rome on American political institutions. In this issue of Humanities, classicists look behind the monu mental facades to examine what the ancient republics have contributed to American culture. Essays by Meyer Reinhold of Boston University and Susan Ford Wiltshire of Vanderbilt University demonstrate that the classical This elevation drawing showing a side civilizations inspired not only the mechanism and shape of American gov view of the marble memorial to Thomas ernment but also the values of statehood that continue to affect American Jefferson in Washington, D.C., was is political life. sued by the architectural firm of John In the same spirit that moved Charles Bulfinch to base his design for Russell Pope in January 1939. Inspired the dome of the U.S. Capitol on classical models, his son, Thomas Bulfinch, by the Pantheon in Rome and honoring brought classical mythology to a broad American audience. Marie Cleary, Jefferson's own classically influenced ar who is currently at work on a biography of the younger Bulfinch, describes chitecture, the monument is a symbol of the American heritage of republican gov in an essay on The Age of Fable how Bulfinch brought knowledge of the clas ernment and civic virtue. sical gods and heroes to generations of Americans. The NEH fosters goals similar to those achieved by Bulfinch by supporting projects that increase the awareness of the presence of the classical past in American politics and culture. -

Renaissance and Reformation, 1978-79

Sound and Silence in Ariosto's Narrative DANIEL ROLFS Ever attentive to the Renaissance ideals of balance and harmony, the poet of the Orlando Furioso, in justifying an abrupt transition from one episode of his work to another, compares his method to that of the player of an instrument, who constantly changes chord and varies tone, striving now for the flat, now for the sharp. ^ Certainly this and other similar analogies of author to musician^ well characterize much of the artistry of Ludovico Ariosto, who, like Tasso, even among major poets possesses an unusually keen ear, and who continually enhances his narrative by means of imaginative and often complex plays upon sound. The same keenness of ear, however, also enables Ariosto to enrich numerous scenes and episodes of his poem through the creation of the deepest of silences. The purpose of the present study is to examine and to illustrate the wide range of his literary techniques in each regard. While much of the poet's sensitivity to the aural can readily be observed in his similes alone, many of which contain a vivid auditory component,^ his more significant treatments of sound are of course found throughout entire passages of his work. Let us now turn to such passages, which, for the convenience of the non-speciaUst, will be cited in our discussion both in the Italian text edited by Remo Ceserani, and in the excellent English prose translation by Allan Gilbert."* In one instance, contrasting sounds, or perhaps more accurately, the trans- formation of one sound into another, even serves the implied didactic content of an episode with respect to the important theme of distin- guishing illusion from reality. -

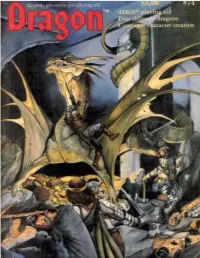

DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) Is Pub- the Occasion, and It Is Now So Noted

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chid: Kim Mohan Quiet celebration Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Roger Raupp Birthdays dont hold as much meaning Patrick L. Price Vol. VII, No. 12 June 1983 for us any more as they did when we were Mary Kirchoff younger. That statement is true for just Office staff: Sharon Walton SPECIAL ATTRACTION about all of us, of just about any age, and Pam Maloney its true of this old magazine, too. Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel June 1983 is the seventh anniversary of The DRAGON Magazine Contributing editors: Roger Moore Combat Computer . .40 Ed Greenwood the first issue of DRAGON Magazine. A playing aid that cant miss National advertising representative: In one way or another, we made a pretty Robert Dewey big thing of birthdays one through five c/o Robert LaBudde & Associates, Inc. if you have those issues, you know what I 2640 Golf Road mean. Birthday number six came and OTHER FEATURES Glenview IL 60025 Phone (312) 724-5860 went without quite as much fanfare, and Landragons . 12 now, for number seven, weve decided on Wingless wonders This issues contributing artists: a quiet celebration. (Maybe well have a Jim Holloway Phil Foglio few friends over to the cave, but thats The electrum dragon . .17 Timothy Truman Dave Trampier about it.) Roger Raupp Last of the metallic monsters? This is as good a place as any to note Seven swords . 18 DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- the occasion, and it is now so noted. Have Blades youll find bearable lished monthly for a subscription price of $24 per a quiet celebration of your own on our year by Dragon Publishing, a division of TSR behalf, if youve a mind to, and I hope Hobbies, Inc. -

HS-Required-Reading-Assignment

Accredited with – SACS/CASI/AdvancedEd - NIPSA Required High School Summer Assignment Summer Reading: (1) Read two books from this list, or one book from this list and one biography, memoir, or autobiography or other book of your own choosing. Any edition or translation is fine. These recommendations include many traditional “classics” of western culture, as well as suggestions for discovering other world masterworks. (2) Create a carefully designed and well executed product that will persuade others to read the books you chose. Due the first day of school! Homer, The Iliad Homer, The Odyssey Ovid, Metamorphoses Virgil, The Aeneid Dante, The Inferno Edith Hamilton, Mythology Thomas Bulfinch, Mythology Shakespeare, The Tempest, Julius Caesar, etc. Swift, Gulliver’s Travels Defoe, Robinson Crusoe Frances Hodgson Burnett, The Secret Garden Poetry by Blake, Keats, Shelley, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Tennyson, Christina Rosetti Any work by Jane Austin, Mary Shelley, Emily Bronte, Charlotte Bronte, Charles Dickens, Joseph Conrad, Somerset Maugham, Evelyn Waugh, or Virginia Woolf Earnest Hemingway, A Farewell To Arms, his Africa stories, etc. John Steinbeck, Travels With Charlie, etc. Patrick O’Brian, Master and Commander, The Far Side of the World Albert Camus, The Stranger Julia Alvarez, How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents or other works by Alvarez Any book by Isabel Allende, especially her books for youth Poetry by Pablo Neruda Julia Butterfly Hill, The Legacy of Luna Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire Carl Hiassen, Hoot, etc. Patrick Smith, A Land Remembered Lucy and Steven Hawking, George’s Cosmic Treasure Hunt Helene Cooper, The House at Sugar Beach Any work by Edgar Allen Poe, H.P. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Bulfinch's Mythology: the Age of Fable, by Thomas Bulfinch

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Bulfinch's Mythology: The Age of Fable, by Thomas Bulfinch This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Bulfinch's Mythology: The Age of Fable Author: Thomas Bulfinch Posting Date: February 4, 2012 [EBook #3327] Release Date: July 2002 First Posted: April 2, 2001 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BULFINCH'S MYTHOLOGY: AGE OF FABLE *** Produced by an anonymous Project Gutenberg volunteer. BULFINCH'S MYTHOLOGY THE AGE OF FABLE Revised by Rev. E. E. Hale CONTENTS Chapter I Origin of Greeks and Romans. The Aryan Family. The Divinities of these Nations. Character of the Romans. Greek notion of the World. Dawn, Sun, and Moon. Jupiter and the gods of Olympus. Foreign gods. Latin Names.-- Saturn or Kronos. Titans. Juno, Vulcan, Mars, Phoebus-Apollo, Venus, Cupid, Minerva, Mercury, Ceres, Bacchus. The Muses. The Graces. The Fates. The Furies. Pan. The Satyrs. Momus. Plutus. Roman gods. Chapter II Roman Idea of Creation. Golden Age. Milky Way. Parnassus. The Deluge. Deucalion and Pyrrha. Pandora. Prometheus. Apollo and Daphne. Pyramus and Thisbe. Davy's Safety Lamp. Cephalus and Procris Chapter III Juno. Syrinx, or Pandean Pipes. Argus's Eyes. Io. Callisto Constellations of Great and Little Bear. Pole-star. Diana. Actaeon. Latona. Rustics turned to Frogs. Isle of Delos. Phaeton. -

The Moslem Enemy in Renaissance Epic: Ariosto, Tasso, and Camoens

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History, Department of 1-1-1977 The oM slem Enemy in Renaissance Epic: Ariosto, Tasso, and Camoens John Donnelly Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Yale Italian Studies, Vol. I, No. 1 (1977): 162-170. © 1977 Yale Italian Studies. Used with permission. The Moslem Enemy in Renaissance Epic: Ariosto, Tasso and Camoens John Patrick Donnelly, S.J. The Renaissance produced many tracts and descriptions dealing with Mos- lems, such as those by Ogier de Busbecq and Phillipe du Fresne-Canaye,' which remain the main source for gauging western attitudes toward Moslems, but these can be supplemented by popular literature which reflects, forms, and gives classic expression to the ideas and stereotypes of a culture.' This study examines and compares the image.of the Moslem in the three greatest epics of the sixteenth century, Ariosto's Orlando furioso, Tasso's Gerusalemme liberata, and Camoens's Os Lusiadas." All three epics enjoyed wide popularity and present Christian heroes struggling against Moslem enemies. Ludovico Ariosto, courtier to the d'Este lords of Ferrara, first published Orlando furioso in 1516 but continued to polish and expand it until 1532. With 38,728 lines, it is the longest poem of the Renaissance, perhaps of west- ern literature, to attain wide popularity. It describes the defense of Paris by Charlemagne and his knights against the Moors of Spain and Africa. This was traditional material already developed by the medieval chansons de geste and by Orlando innamorato of Matteo Maria Boiardo, who preceded Ariosto as court poet at Ferrara. -

^ I F T G L F T S I D

*• .V. A: 3 rTfy!'?f 'iW ft'-’' &&m h ^ iftglftsiDum An Independent Newspaper ©evoted to the Interests of the People of Hightstown and Vicinity 116TH YEAR-No. 36 HIGHTSTOWN GAZETTE, MERCER COUNTY, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, MARCH 4, 1965 PRICE-FIVE CENTS Westerlea Apartments GOP Meeting Require Outside Mirror Pool Plan Withdrawn Fooling With An application to build a private To Disclose On New Passenger Cars swimming pool at the Westerlea Knife Costs Apartments off South Main street Motor Vehicle Director June Stre- on the driver's side. However, if has been temporarily withdrawn, Bank Project lecki today reminded purchasers of the driver's view in the rear mirror Joseph Hoch, chairman of the Man His Life new passnger vehicles of the re is obstructed or obscured by con Borough Zoning Board of Ad quirement that all vehicles manufac struction design or by load, the ve justment, announced over the Director Coates Will tured and sold after January 1 be hicle must be equipped with an ex weekend. Find Migrant Laborer equipped with a rear view mirror terior mirror on the side of the ve Detail First Public and an exterior mirror on the driv hicle opposite the driver’s side. An attorney for the apartment toead in 2d Incident er’s side. owner told the board he would Airing of Project Miss Strelecki pointed out that submit an altered plan later. His On Cranbury Farm This new law also specifies that what the law simply says is if you original annlication was met with every commercial vehicle registered cannot observe the traffic pattern objections from neighbors at a The proposed face-lifting of the in this state, other than a trailer or through your rear view mirror, you session of the board last month. -

Hercules Abstracts

Hercules: A hero for all ages Hover the mouse over the panel title, hold the Ctrl key and right click to jump to the panel. 1a) Hercules and the Christians ................................... 1 1b) The Tragic Hero ..................................................... 3 2a) Late Mediaeval Florence and Beyond .................... 5 2b) The Comic Hero ..................................................... 7 3a) The Victorian Age ................................................... 8 3b) Modern Popular Culture ....................................... 10 4a) Herculean Emblems ............................................. 11 4b) Hercules at the Crossroads .................................. 12 5a) Hercules in France ............................................... 13 5b) A Hero for Children? ............................................ 15 6a) C18th Political Imagery ......................................... 17 6b) C19th-C21st Literature ........................................... 19 7) Vice or Virtue (plenary panel) ............................... 20 8) Antipodean Hercules (plenary panel) ................... 22 1a) Hercules and the Christians Arlene Allan (University of Otago) Apprehending Christ through Herakles: “Christ-curious” Greeks and Revelation 5-6 Primarily (but not exclusively) in the first half of the twentieth century, scholarly interest has focussed on the possible influence of the mythology of Herakles and the allegorizing of his trials amongst philosophers (especially the Stoics) on the shaping of the Gospel narratives of Jesus. This -

Bulfinch's Mythology

Bulfinch's Mythology Thomas Bulfinch Bulfinch's Mythology Table of Contents Bulfinch's Mythology..........................................................................................................................................1 Thomas Bulfinch......................................................................................................................................1 PUBLISHERS' PREFACE......................................................................................................................3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE...........................................................................................................................4 STORIES OF GODS AND HEROES..................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................7 CHAPTER II. PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA...............................................................................13 CHAPTER III. APOLLO AND DAPHNEPYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS7 CHAPTER IV. JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTODIANA AND ACTAEONLATONA2 AND THE RUSTICS CHAPTER V. PHAETON.....................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER VI. MIDASBAUCIS AND PHILEMON........................................................................31 CHAPTER VII. PROSERPINEGLAUCUS AND SCYLLA............................................................34