An Overview of Non-Avian Theropod Discoveries and Classification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fused and Vaulted Nasals of Tyrannosaurid Dinosaurs: Implications for Cranial Strength and Feeding Mechanics

Fused and vaulted nasals of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs: Implications for cranial strength and feeding mechanics ERIC SNIVELY, DONALD M. HENDERSON, and DOUG S. PHILLIPS Snively, E., Henderson, D.M., and Phillips, D.S. 2006. Fused and vaulted nasals of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs: Implications for cranial strength and feeding mechanics. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51 (3): 435–454. Tyrannosaurid theropods display several unusual adaptations of the skulls and teeth. Their nasals are fused and vaulted, suggesting that these elements braced the cranium against high feeding forces. Exceptionally high strengths of maxillary teeth in Tyrannosaurus rex indicate that it could exert relatively greater feeding forces than other tyrannosaurids. Areas and second moments of area of the nasals, calculated from CT cross−sections, show higher nasal strengths for large tyrannosaurids than for Allosaurus fragilis. Cross−sectional geometry of theropod crania reveals high second moments of area in tyrannosaurids, with resulting high strengths in bending and torsion, when compared with the crania of similarly sized theropods. In tyrannosaurids trends of strength increase are positively allomeric and have similar allometric expo− nents, indicating correlated progression towards unusually high strengths of the feeding apparatus. Fused, arched nasals and broad crania of tyrannosaurids are consistent with deep bites that impacted bone and powerful lateral movements of the head for dismembering prey. Key words: Theropoda, Carnosauria, Tyrannosauridae, biomechanics, feeding mechanics, computer modeling, com− puted tomography. Eric Snively [[email protected]], Department of Biological Sciences, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive NW, Calgary, Alberta T2N 1N4, Canada; Donald M. Henderson [[email protected]], Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, Box 7500, Drumheller, Alberta T0J 0Y0, Canada; Doug S. -

PALEONTOLOGY and BIOSTRATIGRAPHY of MONGOLIA the JOINT SOVIET-MONGOLIAN PALEONTOLOGICAL EXPEDITION (Transactions, Vol

PALEONTOLOGY AND BIOSTRATIGRAPHY OF MONGOLIA THE JOINT SOVIET-MONGOLIAN PALEONTOLOGICAL EXPEDITION (Transactions, vol. 3) EDITORIAL BOARD: N. N. Kramarenko (editor-in-chief) B. Luvsandansan, Yu. I. Voronin, R. Barsbold, A. K. Rozhdestvensky, B. A. Trofimov, V. Yu. Reshetov 1976 S. M. Kurzanov A NEW CARNOSAUR FROM THE LATE CRETACEOUS OF NOGON-TSAV, MONGOLIA* The Upper Cretaceous locality of Nogon-Tsav, located in the Zaltaika Gobi, 20 km NW of Mt. Ongon-Ulan-Ula, was discovered by geologists of the MNR. Then, in a series of years (1969–1971, 1973) the joint Soviet-Mongolian Geological Expedition investigated the site. According to the oral report of B. Yu. Reshetova, the deposits in this region are composed basically of sandstone and clay, clearly subdivided into two deposits. The lower great thickness contains many complete skulls, separate bones of tarbosaurs, ornithomimids, and claws of therizinosaurs. The upper red-colored beds are characterized only by scattered fragments of skulls. The fragments described below are of a new carnivorous dinosaur, Alioramus remotus (coll. South Goby region), from the family Tyrannosauridae, which occurs in the lower gray beds. Genus Alioramus Kurzanov, gen. nov. G e n u s n a m e from alius (Lat.) – other, ramus (Lat.) – branch; masc. G e n o t y p e — A. remotus Kurzanov, sp. nov., Upper Cretaceous, Nemegetinskaya suite, southern Mongolia. D i a g n o s i s . Tyrannosaurid of average size. Skull low, with highly elongated jaws. Nasals with well-developed separate crests of 1–l.5 cm height. Second antorbital fenestrae displaced forward, reaching the anterior end of the 5th tooth. -

From the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia

AMEGHINIANA (Rev. Asoc. Paleontol. Argent.) - 40 (1): 119-122. Buenos Aires, 30-03-2003 ISSN0002-7014 NOTA PALEONTOLÓGICA A new specimen of Patagonykus puertai (Theropoda: Alvarezsauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia Luis M. CHIAPPE1and Rodolfo A. CORIA2 Introduction Systematic paleontology With their short and robust forelimbs, highly ki- THEROPODA netic skulls, and a host of unique skeletal features, COELUROSAURIA alvarezsaurids are highly specialized Mesozoic ALVAREZSAURIDAEBonaparte, 1991 coelurosaurian theropods known from the Late Cretaceous of Asia, North, and South America Genus PatagonykusNovas, 1997a (Chiappe et al., 2002). Despite abundant and well- preserved material from the Gobi Desert of Patagonykussp. cf. P. puertaiNovas, 1997a Mongolia, the phylogenetic relationships of al- Figures 1 and 2 varezsaurids have remained unclear (Chiappe et Material. MCF-PVPH-102 (Museo Carmen Funes, al., 2002; Novas and Pol, 2002; Suzuki et al., 2002). Paleontología de Vertebrados; Plaza Huincul, The most basal alvarezsaurids are from South Neuquén, Argentina), an articulated phalanx 1 and 2 America and are limited to just two taxa from the (ungual) of the left manual digit I. Patagonian province of Neuquén (Argentina), Geographical provenance and geological horizon. Alvarezsaurus calvoi (Bonaparte, 1991) and Northern shore of Los Barriales lake, approximately Patagokykus puertai (Novas, 1997a), which although 80 km north Plaza Huincul. Because the specimen poorly represented are important because they was not collected by professionals, no precise strati- have been consistently interpreted as the most ple- graphic information is available; nonetheless, only siomorphic members of the group (Novas, 1996; the Late Cretaceous Neuquén Group outcrops in this Chiappe et al., 1998). area. Also, considering that the holotype specimen of Here we report on a second specimen of Patagonykus puertaiwas found in beds attributed to Patagonykus, which we assign to the species P. -

Los Restos Directos De Dinosaurios Terópodos (Excluyendo Aves) En España

Canudo, J. I. y Ruiz-Omeñaca, J. I. 2003. Ciencias de la Tierra. Dinosaurios y otros reptiles mesozoicos de España, 26, 347-373. LOS RESTOS DIRECTOS DE DINOSAURIOS TERÓPODOS (EXCLUYENDO AVES) EN ESPAÑA CANUDO1, J. I. y RUIZ-OMEÑACA1,2 J. I. 1 Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra (Área de Paleontología) y Museo Paleontológico. Universidad de Zaragoza. 50009 Zaragoza. [email protected] 2 Paleoymás, S. L. L. Nuestra Señora del Salz, 4, local, 50017 Zaragoza. [email protected] RESUMEN La mayoría de los restos fósiles de dinosaurios terópodos de España son dientes aislados y escasos restos postcraneales. La única excepción es el ornitomimosaurio Pelecanimimus polyodon, del Barremiense de Las Hoyas (Cuenca). Hay registro de terópodos en el Jurásico superior (Oxfordiense superior-Tithónico inferior), en el tránsito Jurásico-Cretácico (Tithónico superior- Berriasiense inferior) y en todos los pisos del Cretácico inferior, con excepción del Valanginiense. En el Cretácico superior únicamente hay restos en el Campaniense y Maastrichtiense. La mayor parte de las determinaciones son demasiado generales, lo que impide conocer algunas de las familias que posiblemente estén representadas. Se han reconocido: Neoceratosauria, Baryonychidae, Ornithomimosauria, Dromaeosauridae, además de terópodos indeterminados, y celurosaurios indeterminados (dientes pequeños sin dentículos). La mayoría de los restos son de Maniraptoriformes, siendo especialmente abundantes los dromeosáuridos. Las únicas excepciones son por el momento, el posible Ceratosauria del Jurásico superior de Asturias, los barionícidos del Hauteriviense-Barremiense de Burgos, Teruel y La Rioja, el posible carcharodontosáurido del Aptiense inferior de Morella y el posible abelisáurido del Campaniense de Laño. Además hay algunos terópodos incertae sedis, como los "paronicodóntidos" (entre los que se incluye Euronychodon), y Richardoestesia. -

New Oviraptorid Dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Nemegt Formation of Southwestern Mongolia

Bull. Natn. Sci. Mus., Tokyo, Ser. C, 30, pp. 95–130, December 22, 2004 New Oviraptorid Dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Nemegt Formation of Southwestern Mongolia Junchang Lü1, Yukimitsu Tomida2, Yoichi Azuma3, Zhiming Dong4 and Yuong-Nam Lee5 1 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100037, China 2 National Science Museum, 3–23–1 Hyakunincho, Shinjukuku, Tokyo 169–0073, Japan 3 Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum, 51–11 Terao, Muroko, Katsuyama 911–8601, Japan 4 Institute of Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China 5 Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources, Geology & Geoinformation Division, 30 Gajeong-dong, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 305–350, South Korea Abstract Nemegtia barsboldi gen. et sp. nov. here described is a new oviraptorid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous (mid-Maastrichtian) Nemegt Formation of southwestern Mongolia. It differs from other oviraptorids in the skull having a well-developed crest, the anterior margin of which is nearly vertical, and the dorsal margin of the skull and the anterior margin of the crest form nearly 90°; the nasal process of the premaxilla being less exposed on the dorsal surface of the skull than those in other known oviraptorids; the length of the frontal being approximately one fourth that of the parietal along the midline of the skull. Phylogenetic analysis shows that Nemegtia barsboldi is more closely related to Citipati osmolskae than to any other oviraptorosaurs. Key words : Nemegt Basin, Mongolia, Nemegt Formation, Late Cretaceous, Oviraptorosauria, Nemegtia. dae, and Caudipterygidae (Barsbold, 1976; Stern- Introduction berg, 1940; Currie, 2000; Clark et al., 2001; Ji et Oviraptorosaurs are generally regarded as non- al., 1998; Zhou and Wang, 2000; Zhou et al., avian theropod dinosaurs (Osborn, 1924; Bars- 2000). -

Xjiiie'icanj/Useum

XJiiie'ican1ox4tatreJ/useum PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 2I8I JUNE 4, I964 Relationships of the Saurischian Dinosaurs BY EDWIN H. COLBERT1 INTRODUCTION The word "Dinosauria" was coined by Sir Richard Owen in 1842 as a designation for various genera and species of extinct reptiles, the fossil bones of which were then being discovered and described in Europe. For many years this term persisted as the name for one order of reptiles and thus became well intrenched within the literature of paleontology. In- deed, since this name was associated with fossil remains that are frequently of large dimensions and spectacular shape and therefore of considerable interest to the general public, it in time became Anglicized, to take its proper place as a common noun in the English language. Almost every- body in the world is today more or less familiar with dinosaurs. As long ago as 1888, H. G. Seeley recognized the fact that the dino- saurs are not contained within a single reptilian order, but rather are quite clearly members of two distinct orders, each of which can be de- fined on the basis of many osteological characters. The structure of the pelvis is particularly useful in the separation of the two dinosaurian orders, and consequently Seeley named these two major taxonomic categories the Saurischia and the Ornithischia. This astute observation by Seeley was not readily accepted, so that for many years following the publication of his original paper proposing the basic dichotomy of the dinosaurs the 1 Chairman and Curator, Department ofVertebrate Paleontology, the American Museum of Natural History. -

Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in Later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2020-0174.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 04-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Holtz, Thomas; University of Maryland at College Park, Department of Geology; NationalDraft Museum of Natural History, Department of Geology Keyword: Dinosaur, Ontogeny, Theropod, Paleocology, Mesozoic, Tyrannosauridae Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Tribute to Dale Russell Issue? : © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 91 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: 2 Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous 3 Asiamerica 4 5 6 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 7 8 Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA 9 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20013 USA 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 ORCID: 0000-0002-2906-4900 Draft 12 13 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 14 Department of Geology 15 8000 Regents Drive 16 University of Maryland 17 College Park, MD 20742 18 USA 19 Phone: 1-301-405-4084 20 Fax: 1-301-314-9661 21 Email address: [email protected] 22 23 1 © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 91 24 ABSTRACT 25 Well-sampled dinosaur communities from the Jurassic through the early Late Cretaceous show 26 greater taxonomic diversity among larger (>50kg) theropod taxa than communities of the 27 Campano-Maastrichtian, particularly to those of eastern/central Asia and Laramidia. -

The Pelvic and Hind Limb Anatomy of the Stem-Sauropodomorph Saturnalia Tupiniquim (Late Triassic, Brazil)

PaleoBios 23(2):1–30, July 15, 2003 © 2003 University of California Museum of Paleontology The pelvic and hind limb anatomy of the stem-sauropodomorph Saturnalia tupiniquim (Late Triassic, Brazil) MAX CARDOSO LANGER Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queens Road, BS8 1RJ Bristol, UK. Current address: Departamento de Biologia, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Av. Bandeirantes, 3900 14040-901 Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil; [email protected] Three partial skeletons allow a nearly complete description of the sacrum, pelvic girdle, and hind limb of the stem- sauropodomorph Saturnalia tupiniquim, from the Late Triassic Santa Maria Formation, South Brazil. The new morphological data gathered from these specimens considerably improves our knowledge of the anatomy of basal dinosaurs, providing the basis for a reassessment of various morphological transformations that occurred in the early evolution of these reptiles. These include an increase in the number of sacral vertebrae, the development of a brevis fossa, the perforation of the acetabulum, the inturning of the femoral head, as well as various modifications in the insertion of the iliofemoral musculature and the tibio-tarsal articulation. In addition, the reconstruction of the pelvic musculature of Saturnalia, along with a study of its locomotion pattern, indicates that the hind limb of early dinosaurs did not perform only a fore-and-aft stiff rotation in the parasagittal plane, but that lateral and medial movements of the leg were also present and important. INTRODUCTION sisting of most of the presacral vertebral series, both sides Saturnalia tupiniquim was described in a preliminary of the pectoral girdle, right humerus, partial right ulna, right fashion by Langer et al. -

The Nonavian Theropod Quadrate II: Systematic Usefulness, Major Trends and Cladistic and Phylogenetic Morphometrics Analyses

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272162807 The nonavian theropod quadrate II: systematic usefulness, major trends and cladistic and phylogenetic morphometrics analyses Article · January 2014 DOI: 10.7287/peerj.preprints.380v2 CITATION READS 1 90 3 authors: Christophe Hendrickx Ricardo Araujo University of the Witwatersrand Technical University of Lisbon 37 PUBLICATIONS 210 CITATIONS 89 PUBLICATIONS 324 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Octávio Mateus University NOVA of Lisbon 224 PUBLICATIONS 2,205 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Nature and Time on Earth - Project for a course and a book for virtual visits to past environments in learning programmes for university students (coordinators Edoardo Martinetto, Emanuel Tschopp, Robert A. Gastaldo) View project Ten Sleep Wyoming Jurassic dinosaurs View project All content following this page was uploaded by Octávio Mateus on 12 February 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The nonavian theropod quadrate II: systematic usefulness, major trends and cladistic and phylogenetic morphometrics analyses Christophe Hendrickx1,2 1Universidade Nova de Lisboa, CICEGe, Departamento de Ciências da Terra, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Quinta da Torre, 2829-516, Caparica, Portugal. 2 Museu da Lourinhã, 9 Rua João Luis de Moura, 2530-158, Lourinhã, Portugal. s t [email protected] n i r P e 2,3,4,5 r Ricardo Araújo P 2 Museu da Lourinhã, 9 Rua João Luis de Moura, 2530-158, Lourinhã, Portugal. 3 Huffington Department of Earth Sciences, Southern Methodist University, PO Box 750395, 75275-0395, Dallas, Texas, USA. -

Colossal New Predatory Dino Terrorized Early Tyrannosaurs 22 November 2013

Colossal new predatory dino terrorized early tyrannosaurs 22 November 2013 dinosaurs ever discovered. The only other carcharodontosaur known from North America is Acrocanthosaurus, which roamed eastern North America more than 10 million years earlier. Siats is only the second carcharodontosaur ever discovered in North America; Acrocanthosaurus, discovered in 1950, was the first. "It's been 63 years since a predator of this size has been named from North America," says Lindsay Zanno, a North Carolina State University paleontologist with a joint appointment at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, and lead author of a Nature Communications paper describing the find. "You can't imagine how thrilled we were to see the bones of this behemoth poking out of the hillside." Zanno and colleague Peter Makovicky, from Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History, discovered the partial skeleton of the new predator in Utah's Cedar Mountain Formation in 2008. The species name acknowledges the Meeker family for its support of early career paleontologists at the Field Museum, including Zanno. This is an illustration of Siats meekerorum. Credit: Jorge Gonzales A new species of carnivorous dinosaur – one of the three largest ever discovered in North America – lived alongside and competed with small-bodied tyrannosaurs 98 million years ago. This newly discovered species, Siats meekerorum, (pronounced see-atch) was the apex predator of its time, and kept tyrannosaurs from assuming top predator roles for millions of years. Named after a cannibalistic man-eating monster from Ute tribal legend, Siats is a species of carcharodontosaur, a group of giant meat-eaters This illustration shows Siats within its ecosystem, eating that includes some of the largest predatory an Eolambia and intimidating early, small-bodied tyrannosauroids. -

Smaller Than You Think Bird-Brained? Need for Speed

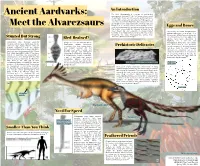

An Introduction The clade Alvarezsauria is a group of small-bodied Ancient Aardvarks: [10] maniraptoran dinosaurs. The first known alvarezsaurid, Alvarezsaurus calvoi, was discovered in partial remains in the late 20th century, and named by Jose F. Bonaparte. A. calvoi was uncovered in Argentina, but today alvarezsaurs are known to have ranged across the Americas, Asia, and Meet the Alvarezsaurs Europe.[10] It is currently estimated that members of this Eggs and Bones clade existed between the Late Jurassic and the Cretaceous. This feather covered bird-like dinosaur is known for its insect based diet and especially its unique hooked The recently discovered Bonapartenykus forelimbs. These highly derived and powerful arms evolved ultimus represents a new genus of of throughout the clade Alvarezsauridae, giving these Alvarezsaurs. A 70 million year old pocket [12] Stunted But Strong dinosaurs a predatory advantage. of fossilized bones and two eggs of this Bird-Brained? species have been discovered in Argentina. This is the first time Alvarezsaurs have strangely powerful Using a cast of a skull from the species Alvarezsaurus bones and egg remains forearms, with one large thumb claw and the Ceratonykus oculatus, researchers have been found in close proximity. other two digits highly reduced. They are reconstructed an alvarezsaurian brain. Prehistoric Delicacies Though evidence of brooding behavior radically transformed from the typical Their analysis revealed that this has been found for other theropod theropod forelimb, which is longer, with three dinosaur had acute hearing and dinosaurs, no conclusion can yet be [10] functional digits and grasping ability. Given excellent eyesight, with intelligence drawn for Alvareszsaurs as no indication their highly specialized nature, it has been comparable to living birds. -

Index of Subjects

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47594-5 — Dinosaurs 4th Edition Index More Information INDEX OF SUBJECTS – – – A Zuul, 275 276 Barrett, Paul, 98, 335 336, 406, 446 447 Ankylosauridae Barrick, R, 383–384 acetabulum, 71, 487 characteristics of, 271–273 basal dinosauromorph, 101 acromial process, 271, 273, 487 cladogram of, 281 basal Iguanodontia, 337 actual diversity, 398 defined, 488 basal Ornithopoda, 336 adenosine diphosphate, see ADP evolution of, 279 Bates, K. T., 236, 360 adenosine triphosphate, see ATP ankylosaurids, 275–276 beak, 489 ADP (adenosine diphosphate), 390, 487 anpsids, 76 belief systems, 474, 489 advanced characters, 55, 487 antediluvian period, 422, 488 Bell, P. R., 162 aerobic metabolism, 391, 487 anterior position, 488 bennettitaleans, 403, 489 – age determination (dinosaur), 354 357 antorbital fenestra, 80, 488 benthic organisms, 464, 489 Age of Dinosaurs, 204, 404–405 Arbour, Victoria, 277 Benton, M. J., 2, 104, 144, 395, 402–403, akinetic movement, see kinetic movement Archibald, J. D., 467, 469 444–445, 477–478 Alexander, R. M., 361 Archosauria, 80, 88–90, 203, 488 Berman, D. S, 236–237 allometry, 351, 487 Archosauromorpha, 79–81, 488 Beurien, Karl, 435 altricial offspring, 230, 487 archosauromorphs, 401 bidirectional respiration, 350 Alvarez, Luis, 455 archosaurs, 203, 401 Big Al, 142 – Alvarez, Walter, 442, 454 455, 481 artifacts, 395 biogeography, 313, 489 Alvarezsauridae, 487 Asaro, Frank, 455 biomass, 415, 489 – alvarezsaurs, 168 169 ascending process of the astragalus, 488 biosphere, 2 alveolus/alveoli,