A Handbook for Classroom Management That Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Use of Playing by the Nursing Staff on Palliative Care for Children With

Original article The use of playing by the nursing staff on palliative care for children with cancer Revista Gaúcha O uso do brincar pela equipe de enfermagem de Enfermagem no cuidado paliativo de crianças com câncer El uso de jugar del equipo de enfermería en cuidados paliativos de niños con cáncer Vanessa Albuquerque Soaresa Liliane Faria da Silvab Emília Gallindo Cursinoc Fernanda Garcia Bezerra Goesd DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1983- ABSTRACT 1447.2014.03.43224 This study aimed to describe ways of using play by the nursing staff on palliative care of children with cancer and analyze the fa- cilitators and barriers of the use of playing on this type of care. Qualitative, descriptive research developed on November 2012 with 11 health professionals, in a public hospital of the state of Rio de Janeiro. Semi-structured interviews and thematic analysis of the information were conducted. The use of playing before procedures was highlighted as a facilitator on palliative care. The child’s physical condition, one’s restriction, resistance of some professionals and the lack of time for developing this activity, made the use of play harder. We concluded that playing enables the child with cancer, in palliative care, a humanized assistance, being fundamental to integrate it on the care for these children. Descriptors: Palliative care. Pediatric nursing. Play and playthings. Neoplasms. RESUMO O estudo teve como objetivos descrever as formas de utilização do brincar pela equipe de enfermagem no cuidado paliativo de crianças com câncer e analisar as facilidades e difi culdades do uso do brincar neste cuidado. -

Compact Disc ARTIST: Devendra Banhart

TRACKS Can't Help But Smiling Angelika Baby Goin' Back First Song For B Last Song For B Chin Chin & Muck Muck 16th & Valencia Roxy Music WEBSITES: Rats Official Compact Disc Maria Lionza MySpace ARTIST: Devendra Banhart Brindo TITLE: What Will We Be (Limited Edition) Meet Me At Lookout Point Walilamdzi Label: WB/Warner Bros. NOTES: Config & Selection #: CD 520960 Foolin' Street Date: 10/27/09 Order Due Date: 10/07/09 UPC: 093624973119 Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $18.98 Alphabetize Under: B OTHER EDITIONS: For the latest up to date info on this release visit WEA.com. ALBUM FACTS Genre: Rock Producers: Devendra Banhart & Paul Butler Special Packaging Info: Includes a 36-page booklet with all illustrations and drawings done by Devandra Description: What Will We Be has a sunny, breezy feel with performances that evoke warm, lazy afternoons spent with good friends. The album is dominated by powerfully melodic, mid-tempo numbers played with relaxed expertise. But there's also ambitious stylistic range displayed with the inclusion of evanescent ballads like "Meet Me At the Lookout Point," the epic riff-rocker "Rats" sprightly R&B flavored groovers on "Baby," and the sultry Latin-flavored stunner "Brindo," the Roxy-inspired "16th & Valencia Roxy Music" among other pleasant surprises. What Will We Be was recorded in a sleepy Northern California town throughout the Spring of 2009, and was co-produced by Paul Butler (from UK outfit Band Of Bees). This is the second album Devendra's recorded with the same crew of players: Noah Georgeson (producer of Banhart's last two albums, Little Joy, Bert Jansch and Joanna Newsome) on guitar and backing vocals, Greg Rogove (Priestbird) on drums and backing vocals; Luckey Remington (The Pleased) on bass and vocals and Rodrigo Amarante (Los Hermanos, Little Joy) on guitar and backing vocals. -

LATIN AMERICA ADVISOR a DAILY PUBLICATION of the DIALOGUE Wednesday, June 15, 2016

LATIN AMERICA ADVISOR A DAILY PUBLICATION OF THE DIALOGUE www.thedialogue.org Wednesday, June 15, 2016 BOARD OF ADVISORS FEATURED Q&A TODAY’S NEWS Diego Arria Director, Columbus Group POLITICAL Devry Boughner Vorwerk How Strong Is Senior Policy Advisor Ex-Argentine Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, LLP Gov’t Minister Joyce Chang Global Head of Research, Temer’s Grip on Arrested, Allegedly JPMorgan Chase & Co. After Hiding Cash W. Bowman Cutter Former Partner, Power in Brazil? José López, who served as public E.M. Warburg Pincus works minister in the government Dirk Donath of former President Cristina Senior Partner, Fernández de Kirchner, was Catterton Aimara arrested after he was allegedly Marlene Fernández Corporate Vice President for seen throwing bags stuffed with Government Relations, millions of dollars over the wall of Arcos Dorados a monastery. Peter Hakim Page 2 President Emeritus, Inter-American Dialogue Donna Hrinak POLITICAL President, Boeing Latin America Brazil’s High Jon Huenemann Vice President, U.S. & Int’l Affairs, Court Rejects Philip Morris International In his fi rst month in offi ce as Brazil’s interim president, Michel Temer lost cabinet members James R. Jones following the release of secret audio recordings. // File Photo: Brazilian Government. Requests for Top Co-chair, Manatt Jones Politicians’ Arrests Global Strategies LLC Interim Brazilian President Michel Temer’s transparency Craig A. Kelly Justice Teori Zavascki rejected Director, Americas International and planning ministers resigned in recent weeks following the request to arrest Senate Gov’t Relations, Exxon Mobil the release of secretly recorded audio tapes in which the President Renan Calheiros, Sen. -

Rodrigo Amarante Shares New Single/Video, “Tango” New Album, Drama, out Next Friday, July 16Th on Polyvinyl

July 8, 2021 For Immediate Release Rodrigo Amarante Shares New Single/Video, “Tango” New Album, Drama, Out Next Friday, July 16th on Polyvinyl (Photo by Eliot Lee Hazel) “[Rodrigo Amarante’s] music has its own push and pull, with three-against-two rhythms and a tangle of instrumental lines — guitars, percussion, a nasal synthesizer, a horn section, some whistling — that interlock but sound like they might collide at any moment. It sounds charmingly ramshackle; it’s not.” — The New York Times “[Rodrigo Amarante’s] rich voice and inventive, genre-crossing arrangements make for music that remains as vital as ever." — The AV Club (“Albums We Can’t Wait to Hear in July”) “...on ‘Drama,’ his first solo record in seven years, the Rio-born and L.A.-based Amarante brings a collection of breezy, tropicalia-soaked songs sung in both Portuguese and English.” — Paste (“The 10 Albums We're Most Excited About in July”) "It's hard to not be captivated by Brazilian singer-songwriter Rodrigo Amarante's limber rhythms and infectious vocal melodies. So, let yourself be.” — MTV News Next Friday, July 16th, Rodrigo Amarante will release his new album, Drama, via Polyvinyl. Today, he presents its third single/video, “Tango,” which may be the key to the theme of the album. Over a buttery melody and accommodating arrangement, “Tango” is a song about a relationship disguised as a partner dancing lesson: exploring one’s need for support, struggling with voicing that, and eventually finding it. “When I wrote this song I was projecting the idea of a love that lasts, one that is mutually supportive and reliable, safe in that sense, and I can't imagine that being possible without a good dose of sense of humor,” says Amarante. -

El Cantautor Brasileño Rodrigo Amarante Dará Su Primer Concierto En El Lunario

Ciudad de México, miércoles 8 de junio de 2016 EL CANTAUTOR BRASILEÑO RODRIGO AMARANTE DARÁ SU PRIMER CONCIERTO EN EL LUNARIO Su presentación, que también será su debut en México, se realizará el martes 13 de julio Interpretará temas de Cavalo, su primer disco como solista, que fusiona bossa nova y pop El cantautor y multi-instrumentalista Rodrigo Amarante, uno de los genios detrás de la popular banda de rock brasileña Los Hermanos y también fundador de la big band de samba Orquestra Imperial, se presentará por primera vez en Lunario el próximo 13 de julio. El concierto de Rodrigo Amarante, presentado por el Lunario, será también el debut del músico brasileño en México. En este foro alterno del Auditorio Nacional ofrecerá un paseo sonoro con lo mejor de su repertorio, en el que incluirá por supuesto temas de su primer álbum como solista Cavalo (2014). Amarante (Río de Janeiro, 6 de septiembre de 1976), quien reside actualmente en Estados Unidos, es una figura destacada de la música sudamericana. Ha grabado y compartido escenario con artistas como Devendra Banhart, Gilberto Gil, Adam Green, Tom Zé y Marisa Monte. El cantautor cobró fama a finales de los 90 con la banda Los Hermanos, que alcanzó popularidad con su tema Anna Julia. Época en la que también participó en la Orquestra Imperial, que acompañó a figuras importantes de la escena pop carioca, como Nina Becker y Moreno Veloso. En 2006 Amarante viajó a California, donde formó junto con Fabrizio Moretti, baterista de The Strokes, y del multi-instrumentalista Binki Shapir, un nuevo grupo de rock llamado Little Joy, el cual lanzó su álbum homónimo en 2008 y fue reconocido no sólo en Estados Unidos sino en otros países. -

May 2013 Grant Gets Threat Forces Kids Books Magnet English Poly Lockdown Teacher Michelle Mitchell Is the Santa a Worried Mother’S Call Put the Fresh- Claus of Books

The Poly Optimist John H. Francis Polytechnic High School Vol. xcviii, No. 10 Serving the Poly Community Since 1913 May 2013 Grant Gets Threat Forces Kids Books Magnet English Poly Lockdown teacher Michelle Mitchell is the Santa A worried mother’s call put the Fresh- Claus of books. man Center in full lockdown mode dur- ing Thursday morning’s CST testing. By Walter Linares Staff Writer By Yenifer Rodriguez we made the call to Freshman Center Editor in Chief teachers,” said DeSantiago. Magnet English teacher Mi- Freshman Center security person- chelle Mitchell received a $5000 nel include DeSantiago, Jeppson, A Parrot freshman is in cus- grant from Pepsi to buy books for dean Gabe Cerna and security aide tody following his alleged threat of kids. 80% went to books, 5% to bags Photo by Lirio Alberto Angie. History teacher Juan Campos violence to the Freshman Center on and tags for the books and 15% to also serves as a dean for the second FUNNY BONE: Evil witch Evilene has a laugh during the drama’s dept’s Thursday, April 28 during the last administrative costs. part of the day staging of 1975’s ‘The Wiz.’ Read the OPTIMIST review on page 3. day of CST testing. “Pepsi provided me with a Visa DeSantiago confi rmed that the “At 8:11 am, a mother called card,” said Mitchell. “Most of the student who allegedly made the saying ‘I’m very worried, there’s books were bought at Borders and threat was never on campus. Teachers Recognized a threat,’” said Freshman Center Amazon. -

Miss Missouri Jr High Performs at Veterans Home Window Display Commemorates World War I Anniversary the Great American Eclipse

Thursday, June 29, 2017 75¢ Cameron, Missouri Tuesday, July 4th For more, log on to: www.mycameronnews.com Miss Missouri Jr High The Great American performs at Veterans Eclipse By Annette Bauer • Have a plan, encourage others who may Editor come to visit to have a plan. Home [email protected] • Be flexible, because we do not know what is going to happen. One prediction is Jackie Beucher from the Astronomical By Annette Bauer for anywhere between 60,000 and 270,000 Society of Kansas City was in Cameron on Editor visitors along a 50 mile corridor of I-35 a Wednesday June 21 to speak to the public [email protected] lot of the traffic is going to be concentrated about the upcoming eclipse on August 21. around Highway 116 because it is the center. Abilene Lortz, Miss Missouri Jr High Vizer told the assembled crowd how • Fill up with gas, because you might be School America 2017, performed on extremely lucky they were because there has parked on the highway for a time. Thursday June 22, playing the piano for the not been a total eclipse in this area for a very • Have water, food, candy for diabetics. veterans as they ate lunch. long time. When shut downs happen on the highway, Lortz said Veterans have a special place Beucher said, ‘It’s all about totality, 99% one of the concerns becomes people’s health. in her heart because her grandfather is a is NOT enough.” • Be as prepared as possible. veteran and there is a veterans home in her Cameron is in the path for totality on • Traffic updates will be available on home town of St. -

Los Hermanos E O Novo Século Da Canção

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE LETRAS AFONSO LUIS FREIBERGER ANTUNES LOS HERMANOS E O NOVO SÉCULO DA CANÇÃO Porto Alegre 2018 AFONSO LUIS FREIBERGER ANTUNES LOS HERMANOS E O NOVO SÉCULO DA CANÇÃO Trabalho de conclusão de curso apresentado à Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul para a obtenção do título de licenciatura em Letras Orientador: Prof. Dr. Carlos Augusto Bonifácio Leite Porto Alegre 2018 AFONSO LUIS FREIBERGER ANTUNES LOS HERMANOS E O NOVO SÉCULO DA CANÇÃO Trabalho de conclusão de curso apresentado à Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul para a obtenção do título de licenciatura em Letras BANCA: Porto Alegre 2018 AGRADECIMENTOS À minha mãe, meu porto seguro, por aquela despretensiosa conversa no carro há sete anos, quando falou que me apoiaria independente das escolhas; por ensinar-me que a revolução está nos pequenos gestos. Ao meu pai, meu melhor amigo, por ter me dado um violão aos 10 anos, um disco do Caetano aos 13 e um livro de poesia aos 17; por ensinar-me a boa luta pela justiça social. À Mariana, meu benzinho, por ter sorrido pra mim numa livraria cinco anos atrás e seguir sorrindo exatamente do mesmo jeito todos os dias desde então; por ensinar-me seu infinito dicionário de ternuras. Aos meus avós, Carmen e Edgar,pelos almoços cotidianos e pelo bom papo; por ensinarem-me na prática o significado da palavra memória. À Gabi, por ter sido desde sempre a parte mais leve de mim; por ensinar-me a dançar sempre na ponta dos pés pelos carpetes dos nossos dias. -

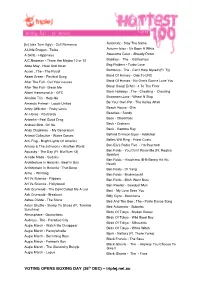

(26Th DEC) – Triplej.Net.Au

1 of 12 [Is] (aka Tom Ugly) - Cult Romance Autokratz - Stay The Same A Little Dragon - Twice Autumn Isles - It's Been A While A Skillz - Happiness Awesome Color - Already Down A.C.Newman - There Are Maybe 10 or 12 Baddies - The - Battleships Abbe May - Howl And Moan Bag Raiders - Turbo Love Acorn , The - The Flood Bamboos , The - Can't Help Myself (Ft. Ty) Adam Green - Festival Song Band Of Horses - Ode To LRC After The Fall - Cut Your Losses Band Of Horses - No One's Gonna Love You After The Fall - Break Me Bang! Bang! Eche! - 4 To The Floor Albert Hammond Jr - GFC Bank Holidays , The - Cheating - Cheating Alkaline Trio - Help Me Basement Jaxx - Wheel N Stop Amanda Palmer - Leeds United Be Your Own Pet - The Kelley Affair Amity Affliction - Fruity Lexia Beach House - Gila An Horse - Postcards Beaches - Sandy Anberlin - Feel Good Drag Beck - Chemtrails Andrew Bird - Oh No Beck - Orphans Andy Clockwise - My Generation Beck - Gamma Ray Animal Collective - Water Curses Behind Crimson Eyes - Addicted Anti-Flag - Bright Lights Of America Belles Will Ring - Priest Coats Antony & The Johnsons - Another World Ben Ely's Radio Five - I'm Psyched Aquasky - The Day (Ft. Blu Rum 13) Ben Folds - You Don't Know Me (Ft. Regina Spektor) Arcade Made - Sudoku Ben Folds - Hiroshima (B-B-Benny Hit His Architecture In Helsinki - Beef In Box Head) Architecture In Helsinki - That Beep Ben Folds - Dr Yang Arms - Whirring Ben Folds - Brainwascht Art Vs Science - Flippers Ben Folds - Bitch Went Nuts Art Vs Science - Hollywood Ben Kweller - Sawdust Man Ash Grunwald - The Devil Called Me A Liar Beni - My Love Sees You Ash Grunwald - Breakout Biffy Clyro - Mountains Ashes Divide - The Stone Bird And The Bee , The - Polite Dance Song Aston Shuffle - Stomp Yo Shoes (Ft. -

Student Handbook As Well As the Home Page

Welcome to Assistance League® of Flintridge Instrumental Music! The ALF Instrumental Music program is one of the most rewarding and exciting educational opportunities offered for our students! ALF is proud to continue its support and administration of this program. We have made the change to a virtual program in light of COVID-19. With COVID restrictions and one-third of LCUSD students Virtual Learners for the year, it is unlikely there will be physical gatherings, although things are ever evolving and we will continue to re-evaluate. We thank you for your patience as we navigate new educational methods designed with the utmost safety in mind. In the following pages you will find information to help your child be successful and get the most out of being a part of the Instrumental Music program. If you still have questions about the overall program, please do not hesitate to contact us. Sincerely, Nancy Gunther, Instrumental Music Chairman 2020-2021 Joanna Petroff, Instrumental Music Assistant Chairman 2020-2021 [email protected] 818-790-2211 Message Anytime Topics 1. Introduction of Teachers & Contact Information 2. Schedules & Calendar 3. Is the ALF Instrumental Music Program Right for your Student? 4. Instruments 5. Class Information 6. Attendance & Commitment 7. Practice Expectations, Private Lessons 8. Behavior Standards For future reference, be sure to download or bookmark this Student Handbook as well as the https://alflintridge.org/programs/instrumental-music/ home page. ® Assistance League of Flintridge Instrumental Music 2020-2021 Music Staff Michael Davis - Brass Instructor La Cañada native Michael Davis enjoys a diverse career both performing and teaching. -

Rodrigo Amarante Returns with New Album, Drama, out 7/16 on Polyvinyl Watch Video for Lead Single “Maré”

May 5, 2021 For Immediate Release Rodrigo Amarante Returns With New Album, Drama, Out 7/16 on Polyvinyl Watch Video for Lead Single “Maré” (Photo Credit: Julia Brokaw) “It feels relaxing to abandon the illusion of verisimilitude and bring forth the confusion and contradiction of what I have to work with, these tales, memory. That is the sound of ‘Drama.’” — Rodrigo Amarante Rodrigo Amarante is thrilled to announce his new album, Drama, out July 16th on Polyvinyl. Drama is the long-awaited follow-up to Amarante’s acclaimed 2014 debut, Cavalo – also being reissued by Polyvinyl, a stunning and intimate collection of songs where “every instrument breathes and every sound blends, yet every moment is distinct” (NPR Music). In conjunction with today’s announcement, Amarante unveils Drama’s lead single, “Maré,” and it’s accompanying self-directed video. An upbeat, seemingly happy song with less jolly aspects hidden beneath the surface, “Maré” is based on Spanish proverb: the tide will fetch what the ebb brings. “Things that arrive in your hand by destiny, they are just as easily swept away,” explains Amarante. About the video, Amarante explains: “This song is about how we shape our destiny and character by what we crave, wish, dream about, despite the outcome. The video is not. That is deliberate. The video is about writing the song, or any song, not about the song itself. It is a representation of writing it, a look on the work that is to produce the magic that is writing, this way looping back to what shapes my own destiny, my wishes and cravings, what the song talks about. -

Working Paper Series Vol 1 Issue 2

WORKING PAPER SERIES 2020 Volume 3 | Special Issue 2 Higher Education and COVID-19 Navigating Careers in the Academy: Gender, Race, and Class www.purdue.edu/butler [email protected] Contents 1 Editors’ Note 1 Mangala Subramaniam 2 Editorial Board Members 4 3 Academic Labor and the Global Pandemic: Revisiting Life-Work Balance under 5 COVID-19* Megha Anwer Purdue University 4 Experiences of Life in a Pandemic: A university community coping with 14 coronavirus Kimberly E. Fox and Norma J. Anderson Bridgewater State University, Massachusetts 5 Contemplating Course Comments, COVID-19 Crisis Communication 29 Challenges, and Considerations – Change vs Color? Marie Allsopp Purdue University 6 Being an International Student in the Age of COVID-19 47 Jaya Bhojwani, Eileen Joy, Abigail Hoxsey, and Amanda Case Purdue University 7 Stranded on Calypso’s Island: Cornerstone, COVID, and power of 61 transformative texts Amanda Mayes and Melinda S. Zook Purdue University 8 Managing Uncertainty in a Pandemic: Transitioning multi-section courses to 73 online delivery Jennifer Hall, Bailey C. Benedict, Elise Taylor, and Seth P. McCullock Purdue University 9 Increasing Access to Food through a Rural Community Pharmacy Initiative 84 Jasmine Gonzalvo and Claire Schumann Purdue University and Northwestern Memorial Hospital 10 Reflections on Institutional Equity for Faculty in Response to COVID-19 92 Dessie Clark, Ethel L. Mickey, and Joya Misra University of Massachusetts Amherst 11 The Inclusive Syllabus Project* 115 Laura Zanotti Purdue University Biographies of Authors 127 *Invited articles. EDITOR’S NOTE Support and Inclusion for Transformative Action Mangala Subramaniam* Purdue University We are all facing challenges because of the uncertainties posed by COVID-19.