Cognitive Architecture. from Biopolitics to Noopolitics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edited by Arne De Boever and Warren Neidich

Book small final_cover new 6/15/13 9:19 AM Pagina 1 This book collects the papers that were presented at Edited by Arne De Boever “The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism: Part One” 1 and Warren Neidich conference in Los Angeles in November 2012. The conference brought together an international array of philosophers, critical theorists, media theorists, art historians, architects, and artists to discuss the state of the mind and the brain under the conditions of cognitive capitalism, in which they have become the new focus of laboring. How have emancipatory politics, art and architecture, and education been redefined by semiocapitalism? What might be the lasting, material ramifications of semiocapitalism on the mind and the brain? The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism: Part One is part of a series that will pursue these and other questions. What is the future of the mind under cognitive capitalism? Can a term such as plastic materialism describe the substantive changes in neural architectures instigated by a contingent cultural habitus? What about the unconscious under these conditions? How might JONATHAN BELLER it be modified, mutated, and modulated by the evolving conditions FRANCO “BIFO” BERARDI of global attention? Is there such a thing as cognitive communism, and what might be its distinctive pathologies? How does artistic ARNE DE BOEVER research—the methods and practices of artistic production and the JODI DEAN knowledge they produce—create new emancipatory possibilities WARREN NEIDICH in opposition to the overwhelming instrumentalization of the PATRICIA PISTERS general intellect under semiocapitalism? JASON SMITH TIZIANA TERRANOVA BRUCE WEXLER ARNE DE BOEVER is Assistant Professor of American Studies in the School of Critical Studies at the California Institute of the Arts. -

The Ouroboros Model, Proposal for Self-Organizing General Cognition Substantiated

Opinion The Ouroboros Model, Proposal for Self-Organizing General Cognition Substantiated Knud Thomsen Paul Scherrer Institut, 5232 Villigen-PSI, Switzerland; [email protected] Abstract: The Ouroboros Model has been proposed as a biologically-inspired comprehensive cog- nitive architecture for general intelligence, comprising natural and artificial manifestations. The approach addresses very diverse fundamental desiderata of research in natural cognition and also artificial intelligence, AI. Here, it is described how the postulated structures have met with supportive evidence over recent years. The associated hypothesized processes could remedy pressing problems plaguing many, and even the most powerful current implementations of AI, including in particular deep neural networks. Some selected recent findings from very different fields are summoned, which illustrate the status and substantiate the proposal. Keywords: biological inspired cognitive architecture; deep neural networks; auto-catalytic genera- tion; self-reflective control; efficiency; robustness; common sense; transparency; trustworthiness 1. Introduction The Ouroboros Model was conceptualized as the basic structure for efficient self- Citation: Thomsen, K. The organizing cognition some time ago [1]. The intention there was to explain facets of natural Ouroboros Model, Proposal for cognition and to derive design recommendations for general artificial intelligence at the Self-Organizing General Cognition same time. Whereas it has been argued based on general considerations that this approach Substantiated. AI 2021, 2, 89–105. can shed some light on a wide variety of topics and problems, in terms of specific and https://doi.org/10.3390/ai2010007 comprehensive implementations the Ouroboros Model still is severely underexplored. Beyond some very rudimentary realizations in safeguards and safety installations, no Academic Editors: Rafał Drezewski˙ actual artificially intelligent system of this type has been built so far. -

Cognitive Computing Systems: Potential and Future

Cognitive Computing Systems: Potential and Future Venkat N Gudivada, Sharath Pankanti, Guna Seetharaman, and Yu Zhang March 2019 1 Characteristics of Cognitive Computing Systems Autonomous systems are self-contained and self-regulated entities which continually evolve them- selves in real-time in response to changes in their environment. Fundamental to this evolution is learning and development. Cognition is the basis for autonomous systems. Human cognition refers to those processes and systems that enable humans to perform both mundane and specialized tasks. Machine cognition refers to similar processes and systems that enable computers perform tasks at a level that rivals human performance. While human cognition employs biological and nat- ural means – brain and mind – for its realization, machine cognition views cognition as a type of computation. Cognitive Computing Systems are autonomous systems and are based on machine cognition. A cognitive system views the mind as a highly parallel information processor, uses vari- ous models for representing information, and employs algorithms for transforming and reasoning with the information. In contrast with conventional software systems, cognitive computing systems effectively deal with ambiguity, and conflicting and missing data. They fuse several sources of multi-modal data and incorporate context into computation. In making a decision or answering a query, they quantify uncertainty, generate multiple hypotheses and supporting evidence, and score hypotheses based on evidence. In other words, cognitive computing systems provide multiple ranked decisions and answers. These systems can elucidate reasoning underlying their decisions/answers. They are stateful, and understand various nuances of communication with humans. They are self-aware, and continuously learn, adapt, and evolve. -

Tyler Coburn Born 1983, New York Lives and Works in New York

Tyler Coburn Born 1983, New York Lives and works in New York EDUCATION Whitney Independent Study Program, Studio Concentration, New York, 2013 – 14 University of Southern California, Roski School of Fine Arts, Los Angeles CA M.F.A. Studio Art, 2012 Yale University, New Haven CT B.A. Literature with an Interdisciplinary Concentration in Visual Culture, 2006 SELECTED EXHIBITIONS AND PROJECTS 2021 vogliamo tutto, OGR, Turin Time Capsule 2045, an Art by Translation project at Palais des Beaux-arts, Paris Tribunalism, an exhibition and conference at Leuphana University Lüneburg 52 Proposals for the 20s, invited by Maria Lind Pizza Piennale, co-organized with Volk Lika, Always Fresh, New York 2020 Counterfactuals, a workshop and project for Wendy’s Subway, New York Counterfactuals, Cultural Capital Introspection (CCI), Ukraine Selfing, two talks and a collective animation project for Home Cooking Archimime, a video collaboration with Aura Rosenberg c/o Meliksetian | Briggs and galleryplatform.la Resonator, an audio work for Infrasonica’s Sonic Realism / Wave #2 Excerpt from Body Work in Sibling Gardens 2, curated by Viktor Timofeev, Montez Press Radio 2019 What We Mean By Freedom, Kunstverein Bielefeld Re-Imagining Futures, curated by Henk Slager, On Curating Project Space, Zurich Report, MMCA Changdong, Seoul 24/7, curated by Sarah Cook, Somerset House, London Self as Actor, NeMe, Cyprus OPEN SCORES. How to program the Commons, panke.gallery, Berlin 2018 Ergonomic Futures, with furniture permanently installed in Centre Pompidou and Museum of Man, Paris Remote Viewer, Koenig & Clinton, New York (solo) Remote Viewer, an animated essay for Tensta Konsthall’s SPACE platform Remote Viewer, a workshop at Triangle Arts Association, New York (in collaboration with Ian Hatcher) On Circulation, Bergen Konsthall Stagings. -

A Knowledge-Based Cognitive Architecture Supported by Machine Learning Algorithms for Interpretable Monitoring of Large-Scale Satellite Networks

sensors Article A Knowledge-Based Cognitive Architecture Supported by Machine Learning Algorithms for Interpretable Monitoring of Large-Scale Satellite Networks John Oyekan 1, Windo Hutabarat 1, Christopher Turner 2,* , Ashutosh Tiwari 1, Hongmei He 3 and Raymon Gompelman 4 1 Department of Automatic Control and Systems Engineering, University of Sheffield, Portobello Street, Sheffield S1 3JD, UK; j.oyekan@sheffield.ac.uk (J.O.); w.hutabarat@sheffield.ac.uk (W.H.); a.tiwari@sheffield.ac.uk (A.T.) 2 Surrey Business School, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey GU2 7XH, UK 3 School of Computer Science and Informatics, De Montfort University, The Gateway, Leicester LE1 9BH, UK; [email protected] 4 IDirect UK Ltd., Derwent House, University Way, Cranfield, Bedfordshire MK43 0AZ, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Cyber–physical systems such as satellite telecommunications networks generate vast amounts of data and currently, very crude data processing is used to extract salient information. Only a small subset of data is used reactively by operators for troubleshooting and finding problems. Sometimes, problematic events in the network may go undetected for weeks before they are reported. This becomes even more challenging as the size of the network grows due to the continuous prolif- Citation: Oyekan, J.; Hutabarat, W.; eration of Internet of Things type devices. To overcome these challenges, this research proposes a Turner, C.; Tiwari, A.; He, H.; knowledge-based cognitive architecture supported by machine learning algorithms for monitoring Gompelman, R. A Knowledge-Based satellite network traffic. The architecture is capable of supporting and augmenting infrastructure Cognitive Architecture Supported by Machine Learning Algorithms for engineers in finding and understanding the causes of faults in network through the fusion of the Interpretable Monitoring of results of machine learning models and rules derived from human domain experience. -

Edited by Warren Neidich

Part Two Final File First Edition_cover part two 5/21/14 9:43 PM Pagina 2 Edited by Warren Neidich ESSAYS BY INA BLOM ARNE DE BOEVER PASCAL GIELEN SANFORD KWINTER MAURIZIO LAZZARATO KARL LYDÉN YANN MOULIER BOUTANG WARREN NEIDICH MATTEO PASQUINELLI ALEXEI PENZIN PATRICIA REED JOHN ROBERTS LISS C. WERNER CHARLES T. WOLFE ARCHIVE BOOKS VOX SERIES Edited by Warren Neidich ESSAYS BY INA BLOM ARNE DE BOEVER PASCAL GIELEN SANFORD KWINTER MAURIZIO LAZZARATO KARL LYDÉN YANN MOULIER BOUTANG WARREN NEIDICH MATTEO PASQUINELLI ALEXEI PENZIN PATRICIA REED JOHN ROBERTS LISS C. WERNER CHARLES T. WOLFE ARCHIVE BOOKS This book collects together extended papers that were presented at The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism: Part Two at ICI Berlin in March 2013. This volume is the second in a series of book that aims attempts to broaden the definition of cognitive capitalism in terms of the scope of its material relations, especially as it relates to the condi- tions of mind and brain in our new world of advanced telecommunica- tion, data mining and social relations. It is our hope to first improve awa- reness of its most repressive charac- teristics and secondly to produce an arsenal of discursive practices with which to combat it. Edited by Warren Neidich Coordinating editor Nicola Guy Proofreading by Theo Barry-Born Designed by Archive Appendix, Berlin Printed by Erredi, Genova Published by Archive Books Dieffenbachstraße 31 10967 Berlin www.archivebooks.org ISBN 978-3-943620-16-0 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Warren Neidich The Early and Late Stages of Cognitive Capitalism .................................... 9 SECTION 1 Cognitive Capitalism The Early Phase Ina Blom Video and Autobiography vs. -

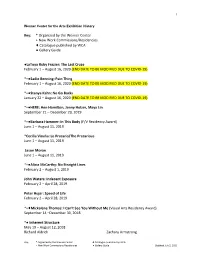

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Theory of Mind in the Sigma Cognitive Architecture

Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Theory of Mind in the Sigma Cognitive Architecture David V. Pynadath1, Paul S. Rosenbloom1;2, and Stacy C. Marsella3 1 Institute for Creative Technologies 2 Department of Computer Science University of Southern California, Los Angeles CA, USA 3 Northeastern University, Boston MA, USA Abstract. One of the most common applications of human intelligence is so- cial interaction, where people must make effective decisions despite uncertainty about the potential behavior of others around them. Reinforcement learning (RL) provides one method for agents to acquire knowledge about such interactions. We investigate different methods of multiagent reinforcement learning within the Sigma cognitive architecture. We leverage Sigma’s architectural mechanism for gradient descent to realize four different approaches to multiagent learning: (1) with no explicit model of the other agent, (2) with a model of the other agent as following an unknown stationary policy, (3) with prior knowledge of the other agent’s possible reward functions, and (4) through inverse reinforcement learn- ing (IRL) of the other agent’s reward function. While the first three variations re-create existing approaches from the literature, the fourth represents a novel combination of RL and IRL for social decision-making. We show how all four styles of adaptive Theory of Mind are realized through Sigma’s same gradient descent algorithm, and we illustrate their behavior within an abstract negotiation task. 1 Introduction Human intelligence faces the daily challenge of interacting with other people. To make effective decisions, people must form beliefs about others and generate expectations about the behavior of others to inform their own behavior. -

Sensory Biology of Aquatic Animals

Jelle Atema Richard R. Fay Arthur N. Popper William N. Tavolga Editors Sensory Biology of Aquatic Animals Springer-Verlag New York Berlin Heidelberg London Paris Tokyo JELLE ATEMA, Boston University Marine Program, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA Richard R. Fay, Parmly Hearing Institute, Loyola University, Chicago, Illinois 60626, USA ARTHUR N. POPPER, Department of Zoology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA WILLIAM N. TAVOLGA, Mote Marine Laboratory, Sarasota, Florida 33577, USA The cover Illustration is a reproduction of Figure 13.3, p. 343 of this volume Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sensory biology of aquatic animals. Papers based on presentations given at an International Conference on the Sensory Biology of Aquatic Animals held, June 24-28, 1985, at the Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Fla. Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. 1. Aquatic animals—Physiology—Congresses. 2. Senses and Sensation—Congresses. I. Atema, Jelle. II. International Conference on the Sensory Biology - . of Aquatic Animals (1985 : Sarasota, Fla.) QL120.S46 1987 591.92 87-9632 © 1988 by Springer-Verlag New York Inc. x —• All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer-Verlag, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York 10010, U.S.A.), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of Information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, Computer Software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use of general descriptive names, trade names, trademarks, etc. -

Neural Cognitive Architectures for Never-Ending Learning

Neural Cognitive Architectures for Never-Ending Learning Author Committee Emmanouil Antonios Platanios Tom Mitchelly www.platanios.org Eric Horvitzz [email protected] Rich Caruanaz Graham Neubigy Abstract Allen Newell argued that the human mind functions as a single system and proposed the notion of a unified theory of cognition (UTC). Most existing work on UTCs has focused on symbolic approaches, such as the Soar architecture (Laird, 2012) and the ACT-R (Anderson et al., 2004) system. However, such approaches limit a system’s ability to perceive information of arbitrary modalities, require a significant amount of human input, and are restrictive in terms of the learning mechanisms they support (supervised learning, semi-supervised learning, reinforcement learning, etc.). For this reason, researchers in machine learning have recently shifted their focus towards subsymbolic processing with methods such as deep learning. Deep learning systems have become a standard for solving prediction problems in multiple application areas including computer vision, natural language processing, and robotics. However, many real-world problems require integrating multiple, distinct modalities of information (e.g., image, audio, language, etc.) in ways that machine learning models cannot currently handle well. Moreover, most deep learning approaches are not able to utilize information learned from solving one problem to directly help in solving another. They are also not capable of never-ending learning, failing on problems that are dynamic, ever-changing, and not fixed a priori, which is true of problems in the real world due to the dynamicity of nature. In this thesis, we aim to bridge the gap between UTCs, deep learning, and never-ending learning. -

Perception, Perfusion & Posture

Perception, Perfusion & Posture Billy L Luu Ph.D. Thesis University of New South Wales 2010 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: LUU First name: BILLY Other name/s: LIANG Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: MEDICAL SCIENCES Faculty: MEDICINE Title: PERCEPTION, PERFUSION & POSTURE Upright posture is a fundamental and critical human behaviour that places unique demands on the brain for motor and cardiovascular control. This thesis examines broad aspects of sensorimotor and cardiovascular function to examine their interdependence, with particular emphasis on the physiological processes operating during standing. How we perceive the forces our muscles exert was investigated by contralateral weight matching in the upper limb. The muscles on one side were weakened to about half their strength by fatigue and by paralysis with curare. In two subjects with dense large-diameter neuropathy, fatigue made lifted objects feel twice as heavy but in normal subjects it made objects feel lighter. Complete paralysis and recovery to half strength also made lifted objects feel lighter. Taken together, these results show that although a signal within the brain is available, this is not how muscle force is normally perceived. Instead, we use a signal that is largely peripheral reafference, which includes a dominant contribution from muscle spindles. Unlike perception of force when lifting weights, it is shown that we perceive only about 15% of the force applied by the legs to balance the body when standing. A series of experiments show that half of the force is provided by passive mechanics and most of the active muscle force is produced by a sub- cortical motor drive that does not give rise to a sense of muscular force through central efference copy or reafference. -

Zootechnologies

Zootechnologies A Media History of Swarm Research SEBASTIAN VEHLKEN Amsterdam University Press Zootechnologies The book series RECURSIONS: THEORIES OF MEDIA, MATERIALITY, AND CULTURAL TECHNIQUES provides a platform for cuttingedge research in the field of media culture studies with a particular focus on the cultural impact of media technology and the materialities of communication. The series aims to be an internationally significant and exciting opening into emerging ideas in media theory ranging from media materialism and hardware-oriented studies to ecology, the post-human, the study of cultural techniques, and recent contributions to media archaeology. The series revolves around key themes: – The material underpinning of media theory – New advances in media archaeology and media philosophy – Studies in cultural techniques These themes resonate with some of the most interesting debates in international media studies, where non-representational thought, the technicity of knowledge formations and new materialities expressed through biological and technological developments are changing the vocabularies of cultural theory. The series is also interested in the mediatic conditions of such theoretical ideas and developing them as media theory. Editorial Board – Jussi Parikka (University of Southampton) – Anna Tuschling (Ruhr-Universität Bochum) – Geoffrey Winthrop-Young (University of British Columbia) Zootechnologies A Media History of Swarm Research Sebastian Vehlken Translated by Valentine A. Pakis Amsterdam University Press This publication is funded by MECS Institute for Advanced Study on Media Cultures of Computer Simulation, Leuphana University Lüneburg (German Research Foundation Project KFOR 1927). Already published as: Zootechnologien. Eine Mediengeschichte der Schwarmforschung, Sebastian Vehlken. Copyright 2012, Diaphanes, Zürich-Berlin. Cover design: Suzan Beijer Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 620 6 e-isbn 978 90 4853 742 6 doi 10.5117/9789462986206 nur 670 © S.