Visualizing the Decline of the Corset Business

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Washington, Wednesday, March 8, 1950 TITLE 5

VOLUME 15 NUMBER 45 Washington, Wednesday, March 8, 1950 TITLE 5— ADMINISTRATIVE (e) “Promotion” is a change from one CONTENTS position to another position of higher PERSONNEL grade, while continuously employed in Agriculture Department Page the same agency. • Chapter I— Civil Service Commiyion See Commodity Credit Corpora (f) “Repromotion” is a change in po tion; Production and Marketing P art 25— F ederal E m plo y e e s ’ P a y sition from a lower grade back to a Administration. higher grade formerly held by the em R eg u latio n s Air Force Department ployee; or to- a higher intermediate SUBPART B— GENERAL COMPENSATION RULES grade, while continuously employed in Rules and regulations: Joint procurement regulations; Subpart B is redesignated as Subpart the same agency. (gp) “Demotion” is a change from one miscellaneous amendments E and a new Subpart B is added as set ( see Army Department). position to another position in a lower out below. These amendments are ef Alien Property, Office of fective the first day of the first pay grade, while continuously employed in period after October 28, 1949, the date the same agency. Notices: of the enactment of the Classification t (h) “Higher grade” is any GS or CPC Vesting orders, etc.: Behrman, Meta----- -------------- 1259 Act of 1949. * grade, the maximum scheduled rate of which is higher than the maximum Coutinho, Caro & Co. et al____ 1259 Sec. scheduled rate of the last previous GS Eickhoff, Mia, et al___________ 1260 25.101 Scope. or CPC grade held by the employee. Erhart, Louis_____------------— 1260 25.102 Definitions. -

The Corset and the Crinoline : a Book of Modes and Costumes from Remote Periods to the Present Time

THE CORSET THE CRINOLINE. # A BOOK oh MODES AND COSTUMES FROM REMOTE PERIODS TO THE PRESENT TIME. By W. B. L. WITH 54 FULL-PAGE AND OTHER ENGRAVINGS. " wha will shoe my fair foot, Aud wha will glove my han' ? And wha will lace my middle jimp Wi' a new-made London ban' ?" Fair Annie of L&hroyan. LONDON: W A R D, LOCK, AND TYLER. WARWICK HOUSE, PATERNOSTER ROW. LOS DOS PRINTKD BY JAS. WAOE, TAVISTOCK STREET, COVBSI GARDEN 10 PREFACE. The subject which we have here treated is a sort of figurative battle-field, where fierce contests have for ages been from time to time waged; and, notwithstanding the determined assaults of the attacking hosts, the contention and its cause remain pretty much as they were at the commencement of the war. We in the matter remain strictly neutral, merely performing the part of the public's " own correspondent," making it our duty to gather together such extracts from despatches, both ancient and modern, as may prove interesting or important, to take note of the vicissitudes of war, mark its various phases, and, in fine, to do our best to lay clearly before our readers the historical facts—experiences and arguments—relating to the much-discussed " Corset question" As most of our readers are aware, the leading journals especially intended for the perusal of ladies have been for many years the media for the exchange of a vast number of letters and papers touching the use of the Corset. The questions relating to the history of this apparently indispensable article of ladies' attire, its construction, application, and influence on the figure have become so numerous of late that we have thought, by embodying all that we can glean and garner relating to Corsets, their wearers, and the various costumes worn by ladies at different periods, arranging the subject-matter in its due order as to dates, and at the same time availing ourselves of careful illustration when needed, that an interesting volume would result. -

SWART, RENSKA L." 12/06/2016 Matches 149

Collection Contains text "SWART, RENSKA L." 12/06/2016 Matches 149 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Title/Description Date Status Home Location O 0063.001.0001.008 PLAIN TALK TICKET 1892 OK MCHS Building Ticket Ticket to a Y.M.C.A. program entitled "Plain Talk, No. 5" with Dr. William M. Welch on the subject of "The Prevention of Contagion." The program was held Thursday, October 27, 1892 at the Central Branch of the YMCA at 15th and Chestnut Street in what appears to be Philadelphia O 0063.001.0002.012 1931 OK MCHS Building Guard, Lingerie Safety pin with chain and snap. On Original marketing card with printed description and instructions. Used to hold up lingerie shoulder straps. Maker: Kantslip Manufacturing Co., Pittsburgh, PA copyright date 1931 O 0063.001.0002.013 OK MCHS Building Case, Eyeglass Brown leather case for eyeglasses. Stamped or pressed trim design. Material has imitation "cracked-leather" pattern. Snap closure, sewn construction. Name inside flap: L. F. Cronmiller 1760 S. Winter St. Salem, OR O 0063.001.0002.018 OK MCHS Building Massager, Scalp Red Rubber disc with knob-shaped handle in center of one side and numerous "teeth" on other side. Label molded into knob side. "Fitch shampoo dissolves dandruff, Fitch brush stimulates circulation 50 cents Massage Brush." 2 1/8" H x 3 1/2" dia. Maker Fitch's. place and date unmarked Page 1 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Title/Description Date Status Home Location O 0063.001.0002.034 OK MCHS Building Purse, Change Folding leather coin purse with push-tab latch. Brown leather with raised pattern. -

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles – c. 1790-1900 1790-1809 – Neoclassicism In the late 18th century, the latest fashions were influenced by the Rococo and Neo-classical tastes of the French royal courts. Elaborate striped silk gowns gave way to plain white ones made from printed cotton, calico or muslin. The dresses were typically high-waisted (empire line) narrow tubular shifts, unboned and unfitted, but their minimalist style and tight silhouette would have made them extremely unforgiving! Underneath these dresses, the wearer would have worn a cotton shift, under-slip and half-stays (similar to a corset) stiffened with strips of whalebone to support the bust, but it would have been impossible for them to have worn the multiple layers of foundation garments that they had done previously. (Left) Fashion plate showing the neoclassical style of dresses popular in the late 18th century (Right) a similar style ball- gown in the museum’s collections, reputedly worn at the Duchess of Richmond’s ball (1815) There was public outcry about these “naked fashions,” but by modern standards, the quantity of underclothes worn was far from alarming. What was so shocking to the Regency sense of prudery was the novelty of a dress made of such transparent material as to allow a “liberal revelation of the human shape” compared to what had gone before, when the aim had been to conceal the figure. Women adopted split-leg drawers, which had previously been the preserve of men, and subsequently pantalettes (pantaloons), where the lower section of the leg was intended to be seen, which was deemed even more shocking! On a practical note, wearing a short sleeved thin muslin shift dress in the cold British climate would have been far from ideal, which gave way to a growing trend for wearing stoles, capes and pelisses to provide additional warmth. -

Regulation 4316R Athletic Uniforms, Dress Code, and Student Athlete Modesty

Regulation 4316R Athletic Uniforms, Dress Code, and Student Athlete Modesty Background From time-to-time concerns arise regarding the lack of modesty provided by some athletic and other extra-curricular uniforms. Since uniforms are usually designed for optimal performance, several do not comply with the school system’s Board policy for student dress during the instructional day (School Board Policy 4316 – Student Dress Codes). Singlet tops, jersey design, short length, skirt length, and swimsuit cuts seem to draw the most frequent concerns. A review of all uniforms indicates that volleyball, cheerleading, wrestling, track, cross country, tennis, and swimming have design features that could cause modesty concerns. Regulation The following language is adapted from the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS). NFHS regulations are used by the North Carolina High School Athletic Association (NCHSAA) to specify uniform requirements. Schools may not require modifications to uniforms that inhibit athletic performance. However, individual student athletes will be allowed to make the following modifications as long as the uniform meets all requirements set forth by the NCHSAA and NFHS. Uniform Tops o Tops may be worn with a single solid colored t-shirt or similar undergarment. o The color for any t-shirt or similar undergarment shall be solid and must be pre- approved by the school o The solid color shall be the predominant color of the uniform top. o T-shirts or similar undergarments shall match in color and design among student athletes on the same team. o All other NCHSAA and NFHS uniform top regulations shall apply. Uniform Bottoms o Uniform bottoms that are shorts or skirts may include a visible undergarment that is of mid-thigh or knee length. -

Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eoN - Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa University of Copenhagen Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Gaspa, Salvatore, "Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eN o-Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 3. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The Neo- Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa, University of Copenhagen In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. -

Undergarments : Extension Circular 4-12-2

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska 4-H Clubs: Historical Materials and Publications 4-H Youth Development 1951 Undergarments : Extension Circular 4-12-2 Allegra Wilkens Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/a4hhistory Part of the Service Learning Commons Wilkens, Allegra, "Undergarments : Extension Circular 4-12-2" (1951). Nebraska 4-H Clubs: Historical Materials and Publications. 124. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/a4hhistory/124 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 4-H Youth Development at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska 4-H Clubs: Historical Materials and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Jan. 1951 E.G. 4-12-2 o PREPARED FOR 4-H CLOTHrNG ClUB GIRLS EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE COOPERATING A W. V. LAMBERT, DIRECTOR C i ( Undergarments for the Well Dressed 4-H Girl Allegra Wilkens The choosing or designing of the undergarments that will make a suitable foundation for her costume is a challenge to any girl's good taste. She may have attractive under- wear if she is wise in the selection of materials and careful in making it or in choosing ready-made garments. It is not the amount of money that one spends so much as it is good judgment in the choice of styles, materials and trimmings. No matter how beautiful or appropriate a girl's outer garments may be, she is not well dressed unless she has used good judgment in making or selecting her under - wear. -

2017-2018 Acs Dress Code

2017-2018 ACS DRESS CODE K- 12th grade students are required to wear the regular uniform on all non-P.E. days (2 days a week). Parents will be notified of any exceptions. Should a violation of the dress code occur, the student’s homeroom teacher will address the matter verbally with the student and in written form with the parents. A second violation will result in a phone call to parents requesting a change of clothes be brought to school. All subsequent violations will require a uniform rental fee of $5.00 per incident and the student will be allowed to borrow an article of clothing from the used uniform shelf. Students will be responsible for laundering and returning the article of clothing the next day. A. Girls’ Required Regular Uniform: 1. Clothing a) Navy or khaki pants b) Navy or khaki knee-length shorts, skort or jumper with solid navy or white tights or leggings (Please note: shorts, skorts and skirts must reach to within 2” of the top of the knee) c) Navy, white or light blue collared long or short sleeve shirts with ACS logo d) Solid white or navy socks e) Jeans may be worn every Friday. Boots, loafers and athletic shoes are also acceptable on Fridays only. No sandals please. 2. Shoes - Shoes must be brown, black or navy blue lace-up oxfords, loafers, or athletic shoes. Students may NOT wear sandals. Girls May Wear: 1. Clothing a) Navy cardigan with ACS logo b) Navy or white turtleneck or “under armor” (only as an undergarment on cold days) 2. -

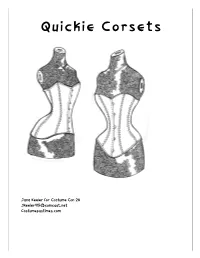

Quickie Corsets

Quickie Corsets Jana Keeler for Costume Con 26 [email protected] Costumepastimes.com A corset can be as complicated and armor-plated as you want—some make them three layers thick out of the stiffest material they can find. But there are times when you just want to whip something up as quickly as you can but still have it be functional and hopefully give you an approximation of the correct silhouette. I’m going to show you how to create a Victorian corset in a couple of different ways. Now, I don’t have a magic way to create a corset in an hour---I’m sure someone out there has figured out how to do that and god bless ‘em! Step One – Get A Pattern: there are a lot of sources for corset patterns these days. You can certainly draft one yourself but why, when there are so many companies doing some nice corset patterns and save yourself some time. • Simplicity.com – “B” to the right is their pattern #5726 and comes in sizes 6 through 20. They also have #7215 and #9769. • McCalls.com (mccallpattern.com) – they have M3609 in sizes 4-18. • Butterick.com – one of my favorites for a fast corset is B4254 in sizes 6-22. • Past Patterns (pastpatterns.com) – #213 in size 8-26 is one of the first corset patterns I found and another one of my favorites. • Farthingales (farthingales.on.ca) – they carry corset patterns and kits. They have detailed instructions on how to put together the Simplicity #9769 corset. They also have photos of different corsets on the same person to see the different fits. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat.