N E T a J I' S LIFE and WRITINGS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

'Netaji's Life Was More Important Than the Legends and Myths' Page 1 of 4

The Telegraph Page 1 of 4 Issue Date: Sunday , July 10 , 2011 ‘Netaji’s life was more important than the legends and myths’ Miami-based economist turned film-maker Suman Ghosh — who has also made a documentary on Amartya Sen — was in conversation with Sugata Bose, Netaji’s grandnephew, about the historian’s His Majesty’s Opponent — Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Struggle Against Empire on the morning of the launch of the Penguin book. Metro sat in on the Netaji adda. Excerpts… Suman Ghosh: You are a direct descendent of Subhas Chandra Bose and your father (Sisir Kumar Bose) was involved in the freedom struggle with him. Did you worry about objectivity in treating a subject that was so close to you? Sugata Bose: I made a conscious decision to write this book as a historian. Not as a Sugata Bose speaks with (right) family member. My father always used to tell me that Netaji believed that his country and Suman Ghosh at Netaji Bhavan. family were coterminous. So if I’m a member of the Bose family by an accident of birth so Picture by Bishwarup Dutta are all of the people of India. In some ways, if there is a problem of objectivity it would apply to most people and scholars of the subcontinent. But I felt I had acquired the necessary critical distance from my subject to embark on this project when I did. Ghosh: Netaji has always been shrouded in myths and mysteries. He has primarily been characterised as a revolutionary and a warrior. -

Professional-Address.Pdf

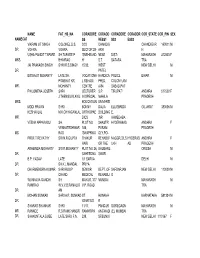

NAME FAT_HS_NA CORADDRE CORADD CORADDRE CORADDR COR_STATE COR_PIN SEX NAMECAT SS RESS1 SS2 ESS3 VIKRAM JIT SINGH COLONEL D.S. 3/33 CHANDIG CHANDIGAR 160011 M DR. VOHRA VOHRA SECTOR 28- ARH H USHA PANDIT TAPARE SH.TAPARE P 'SNEHBAND NEAR DIST- MAHARASH 412803 F MRS. BHIMRAO H' S.T. SATARA TRA JAI PRAKASH SINGH SHRI R.S.SINGH 15/32, WEST NEW DELHI M DR. PATEL BISWAJIT MOHANTY LATE SH. VOCATIONA HANDICA POLICE BIHAR M PRABHAT KR. L REHABI. PPED, COLONY,ANI MR. MOHANTY CENTRE A/84 SABAD,PAT PHILOMENA JOSEPH SHRI LECTURER S.P. TIRUPATI ANDHRA 517502 F J.THENGUVILAYIL IN SPECIAL MAHILA PRADESH MRS. EDUCATION UNIVERSI MODI PRAVIN SHRI BONNY DALIA ELLISBRIDG GUJARAT 380006 M KESHAVLAL M.K.CHHAGANLAL ORTHOPAE BUILDING E, MR. DICS ,NR AHMEDABA VEENA APPARASU SH. PLOT NO SHASTRI HYDERABAD ANDHRA F VENKATESHWAR 188, PURAM PRADESH MS. RAO 'SWAPRIKA' CLY,PO- PROF.T REVATHY SRI N.R.GUPTA THAKUR REHABI.F NAGGR,DILS HYDERAB ANDHRA F HARI OR THE UKH AD PRADESH ARABINDA MOHANTY SRI R.MOHANTY PLOT NO 24, BHUBANE ORISSA M DR. SAHEEDNA SWAR B.P. YADAV LATE 1/1 SARVA DELHI M DR. SH.K.L.MANDAL PRIYA DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHRI ROOP SENIOR DEPT. OF SAFDARJAN NEW DELHI 110029 M DR. CHAND MEDICAL REHABILI G WUNNAVA GANDHI SH MAYUR, 377 MUMBAI MAHARASH M RAMRAO W.V.V.B.RAMALIG V.P. ROAD TRA DR. AM MOHAN SUNKAD SHRI A.R. SUNKAD ST. HONAVA KARNATAKA 581334 M DR. IGNATIUS R SHARAS SHANKAR SHRI 11/17, PANDUR GOREGAON MAHARASH M MR. RANADE R.S.RAMCHANDR RAMKRIPA ANGWADI (E), MUMBAI TRA DR. -

Dr Chandan Basu Is Currently Professor of History in the School of Social Sciences, Netaji Subhas Open University. He Is Also No

Dr Chandan Basu is currently Professor of History in the School of Social Sciences, Netaji Subhas Open University. He is also now the Director of the School of Social Sciences, NOSU. His areas of research are the development of left ideology and politics in West Bengal, the social history of modern Bengal and the gender studies. The Email ID of Dr Basu is [email protected]. Dr Basu’s publication details are given below: Publications Books 1. The Making of the Left Ideology in West Bengal: Culture, Political Economy, Revolution, 1947 – 1970. New Delhi: Abjjeet Publications, Delhi, 2009. (ISBN 978-93-80031-20-0) 2. Radical Ideology and ‘Controlled Politics’: CPI and the History of West Bengal, 1947-1964. Kolkata: Alphabet Books, 2015. (ISBN 978-81-929635-0-1) Edited Volume 1. Third Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Memorial Lecture (Decolonization and the Crisis of Hindu Nationalism, 1947-52: Sekhar Bandyopadhyay). Kolkata: Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Memorial Lecture, 2012. (Co-edited with Professor Debnarayan Modak) ISBN 978-93-82112-06-8 2. Fourth Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Memorial Lecture (The End Game of the Raj and Subhas Bose’s Political Strategy, 1943-1954: Sabyasachi Bhattacharya). Kolkata, 2013. (Co-edited with Professor Debnarayan Modak) ISBN 978-93-82112- 08-2 3. Gender Sensitization, Women Empowerment and Distance Education: History, Society and Culture. Kolkata: Netaji Subhas Open University, 2014. (Co-edited with Professor Kajal De and Sri Srideep Mukherjee) ISBN 978-93-82112-12-9 4. Fifth Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Memorial Lecture (Search for New Constituencies of Politics: Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Freedom Struggle: Bidyut Chakrabarty). -

District Tpname Sector Email ID Mobile Number TC Address

District TPName Sector Email ID Mobile Number TC Address ACADEMY SUBURBIA, ALIPURDUAR (MACWILL), MAC WILLIAM HIGH SCHOOL, ALIPURDUAR ACADEMY SUBURBIA BEAUTY & WELLNESS [email protected] 9830057338 NEW TOWN, ALIPURDUAR. ACADEMY SUBURBIA, ALIPURDUAR (MACWILL), MAC WILLIAM HIGH SCHOOL, ALIPURDUAR ACADEMY SUBURBIA HEALTHCARE [email protected] 9830057338 NEW TOWN, ALIPURDUAR. ACADEMY SUBURBIA, ALIPURDUAR (MACWILL), MAC WILLIAM HIGH SCHOOL, ALIPURDUAR ACADEMY SUBURBIA IT-ITES [email protected] 9830057338 NEW TOWN, ALIPURDUAR. ACADEMY SUBURBIA, ALIPURDUAR (MACWILL), MAC WILLIAM HIGH SCHOOL, ALIPURDUAR ACADEMY SUBURBIA TOURISM & HOSPITALITY [email protected] 9830057338 NEW TOWN, ALIPURDUAR. PO: ALIPURDUAR COURT, DIST: ALIPURDUAR, PS: ALIPURDUAR, PIN: 736122, ALIPURDUAR ALIPURDUAR DISTRICT YOUTH COMPUTER TRAINING CENTRE ELECTRONICS & HARDWARE [email protected] 9749942008 MADHABMORE ALIPURDUAR, OPPOSITE MUNICIPALITY OFFICE BIRPARA WELFARE ORGANIZATION, VILL+P.O-BIRPARA, P.S- BIRPAARA ALIPURDUAR AMTA NATUN DIGANTA WELFARE SOCIETY BEAUTY & WELLNESS [email protected] 9830809606 MADAREAHAT (NEAR BHUTAN BORDER), DIST- ALIPURDUAR, PIN-735204(W.B), PH- 03563-269001 Bidyanidhi Trust, Alipur Duar; SBI Main Branch Building(2nd Floor) ALIPURDUAR Bidyanidhi Trust IT-ITES [email protected] 9830807505 College Halt, Alipur Duar Pin : 736121 BRIGHT FUTURE .COM KALCHINI CENTRE,KALCHINI MAIN ROAD,PO + PS - ALIPURDUAR BRIGHT FUTURE.COM IT-ITES [email protected] 9609601780 KALCHINI,Dist - ALIPURDUAR, PIN - 735217 -

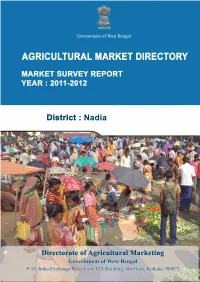

Market Survey Report Year : 2011-2012

GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL AGRICULTURAL MARKET DIRECTORY MARKET SURVEY REPORT YEAR : 2011-2012 DISTRICT : NADIA THE DIRECTORATE OF AGRICULTURAL MARKETING P-16, INDIA EXCHANGE PLACE EXTN. CIT BUILDING, 4 T H F L O O R KOLKATA-700073 THE DIRECTORATE OF AGRICULTURAL MARKETING Government of West Bengal LIST OF MARKETS Nadia District Sl. No. Name of Markets Block/Municipality Page No. 1 Alaipur Beltala Market Chakdah 1 2 Anandanagar Bazar - do - 2 3 Balia Hat - do - 3 4 Banamali Kalitala Bazar - do - 4 5 Bela Mitra Nagar Bazar - do - 5 6 Bishnupur Hat - do - 6 7 Chaudanga Hat - do - 7 8 Chaugachha Naya Bazar - do - 8 9 Chaugachha Puratan Bazar - do - 9 10 Chuadanga Hat - do - 10 11 Dakshin Malopara Market - do - 11 12 Ghetugachi Market - do - 12 13 Gora Chand Tala Bazar - do - 13 14 Hingnara Bazar Hat - do - 14 15 Iswaripur Bazar - do - 15 16 Kadambo Gachi Bazar - do - 16 17 Kali Bazar - do - 17 18 Laknath Bazar - do - 18 19 Madanpur Market - do - 19 20 Narikeldanga Joy Bazar - do - 20 21 Netaji Bazar - do - 21 22 Padmavila Thakurbari Market - do - 22 23 Rasullapur Bazar - do - 23 24 Rasullapur Hat - do - 24 25 Rautari Bazar - do - 25 26 Saguna Bazar - do - 26 27 Sahispur Bazar - do - 27 28 Silinda Bazar - do - 28 29 Simurali Chowmatha Bazar - do - 29 30 Simurali Market - do - 30 31 Sing Bagan Market - do - 31 32 South Chandamari Market - do - 32 33 Sutra Hat - do - 33 34 Tangra Hat - do - 34 35 Tarinipur Hat - do - 35 36 Chakdah Bazar Chakdah Municipality 36 37 Sagnna Bazar ( Only Veg ) - do - 37 38 Sagnna Bazar ( Only Fruits ) - do - 38 39 Goyeshpur ( North ) Gayespur Municipality 39 40 Birohi Bazar Haringhata 40 41 Birohi Cattle Hat - do - 41 42 Boikara Hat - do - 42 43 Dakshin Dutta Para Hat - do - 43 44 Hapania Hat - do - 44 45 Haringhata Ganguria Bazar - do - 45 46 Jhikra Hat - do - 46 47 Jhikra Market - do - 47 48 Kalibazar Hat - do - 48 49 Kastodanga Bazar - do - 49 50 Kastodanga Hat - do - 50 51 Khalsia Hat - do - 51 52 Mohanpur Hat ( 7 No ) - do - 52 53 Mohanpur Market - do - 53 54 Nagarukhra Hat - do - 54 55 Nagarukhra Market - do - 55 Sl. -

JC Bose, SN Bose and KC

International Journal of Librarianship and Administration. ISSN 2231-1300 Volume 6, Number 2 (2015), pp. 143-164 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com Citation profiles of some Indian scientists: J.C. Bose, S.N. Bose and K.C. Kar Gautam Mukhopadhyay Chandrapur College, Chandrapur, Burdwan, 713145, West Bengal, India E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article gives a clear panorama of citation profiles of the research publications of three Indian scientists namely J.C. Bose, S.N. Bose and K.C. Kar. The present study approaches more than one or two scientists taken together and their scientific research contributions (in terms of measurable outputs) as statistical populations. Citations to the scientific research papers by them were collected on checking through Science Citation Index (SCI) and online database of SCI i.e. Web-of-Science (WOS). This paper presents a temporal distribution and the geographical distribution of citations made to the publications of the scientists under study. It has been found that J.C. Bose was the most productive author but K.C. Kar even with much more collaborators was not the same. It has been further noted that S.N. Bose ranked first and was followed by the two other scientists J.C. Bose and K.C. Kar as per the number of total citations received by their scientific papers. Keywords Scientometrics, Scientific Productivity, Citations, Web-of-Science Abbreviations Science Citation Index (SCI), Web-of-Science (WOS) 1 Introduction The significance of individual scientists in the progress of science and technology has been acclaimed over the years. -

SATYENDRA NATH BOSE Santimay Chatterjee Enakshi Chatterjee

SATYENDRA NATH BOSE Santimay Chatterjee Enakshi Chatterjee Contents Preface 1. The Background 2. The Formative-Years (1894-1914) 3. Early Career (1915-1920) 4. The Young Intellectuals 5. First Visit to Europe (1921-1926) 6. Stay at Dacca (1927-1945) 7. Bose at Calcutta (1945-1956) 8. At Santiniketan (1956-1958) 9. The Unconventional Scientist 10. Science through the Mother Tongue 11. The Last Years (1959-1974) 12. The Complete Man References Appendix I List or published papers by S.N. Bose II The Classical Determinism and the Quantum Theory Preface The role of a father figure of Indian science was more or less thrust upon Professor Bose, yet he was grossly misunderstood by many. The image of the idle genius who wasted his powers in intellectual small talk has persisted. It is the task of the biographer to find out if such an image was based on justifiable assumptions. Between the admirers and the detractors, the legend has grown, and the man has been somewhat cast in the background. Bose is perhaps still too close to us historically for a proper perspective. We have made an attempt to show him against the changing times when science was making rapid strides in India, and white doing so other personalities have been drawn into the canvas. We realise, however, the inadequacy of our attempt for Bose was a very complex personality. It would have taken years of research and labour to collect and sort all the materials which, however, are not easily obtainable. Bose’s habit of not keeping any record, letters or diary has further handicapped us; hence some of the information could not be verified. -

Religious Experiments in Colonial Calcutta

FERDINANDO SARDELLA Religious experiments in colonial Calcutta Modern Hinduism and bhakti among the Indian middle class alcutta, 1874: it was one hundred and nine years since the British East India CCompany had taken possession of Bengal, sixteen years since the British Raj officially took over its rule and seventy-three years before Indian inde- pendence.1 A vast and ancient civilisation lived under the rule of the inhabit- ants of a small North Atlantic island, who had managed to project their cul- ture, their religion—and their economic interests—into almost every corner of the globe. It was a time when India was the jewel in the crown of the British Raj and Calcutta had been transformed into a Eurasian metropolis second only to London itself. 1874 was also the year when Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, a Vaishnava of the devotional (bhakti) school of Chaitanya (1486–1534), was born; he died sixty-three years later in 1937. The span of his lifetime was en- trenched in circumstances and events that occurred in and around the city of Calcutta and came to shape the foundation of what is generally known as ‘modern Hinduism’ (the term ‘Hinduism’ will be discussed more in detail at the end of the chapter). For this reason, these years will serve as a suitable focus for this chapter.2 The year 1874 came round at a time of transition in India, when events that began more than a century earlier had started to produce novel patterns of change. In 1757 the Battle of Plassey had paved the way for total domin- ation, as Britain won over French influences in the East. -

Displaced Hindus After Partition in West Bengal1

Südasien-Chronik - South Asia Chronicle 7/2017, S. 123-147 © Südasien-Seminar der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin ISBN: 978-3-86004-330-1 Narrated Time, Constructed Identities: Displaced Hindus after Partition in West Bengal1 ANASUA BASU RAY CHAUDHURY [email protected] KEYWORDS: PARTITION, ORAL HISTORY, KOLKATA, HINDUS, REFUGEE HOMES, SQUATTERS´ COLONY 123 The partition of the Indian sub-continent displaced a large number of people from East Pakistan (or East Bengal as it was popularly known). Unlike the relatively well-off migrants, who could sometimes recon- struct their lives in newer pastures on the other side of the border, for those who were economically not affluent, this was almost an impossi- ble feat. Many had to spend decades in refugee camps before embarking on the vision of a better life. Many could not return to their original occupations leading to a sense of alienation and irreparable occupational loss despite partial rehabilitation in jabar dakhal (squat- ters’) colonies. Refugees who have been surviving in the camps in West Bengal for over six decades and have not yet been rehabilitated are, in a sense, prisoners of the past. It seems that their life and time have been frozen within the boundaries of the camps (Basu Ray Chaudhury 2009: 2-4). This article emphasises the experiences of those displaced Hindus, who crossed the newly-constructed international border between India and Pakistan after 1947, and took refuge in the refugee camps and squatters’ colonies in West Bengal. In order to present a social history of the partition, the article captures the lives and experiences of refu- gees who lived through that "partitioned time". -

1. Letter to Lilavati Asar 2. Letter to Prabhavati1

1. LETTER TO LILAVATI ASAR POONA, August 30, 1945 CHI. LILI, I do not remember having answered your letter. Just now, after the prayer, I have taken out the old letters. This is just to tell you that I think of you. Continue your studies and pass. Do not lose courage. Do not spoil your health. There is no time to write more. Sardar’s treatment is going on. I am well. Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: C.W. 10206. Courtesy: Lilavati Asar 2. LETTER TO PRABHAVATI1 POONA, August 30, 1945 CHI. PRABHA, I do not at all remember whether I have written to you. Your letter of the 1st is lying in front of me. I am writing this after the morning prayer. I hope you keep good health. You may come when you can. Just now I shall have to stay with Sardar in Poona. I may have to be here for three months. After that I shall be touring. You should stay in the Ashram. If there is suitable work for you there and you enjoy peace of mind and keep good health, settle down there. Do as you please. How is Father? Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: G.N. 3579 1 The letters are in the Devanagari script.S VOL. 88 : 30 AUGUST, 1945 - 6 DECEMBER, 1945 1 3. LETTER TO PRABHAVATI1 August 30, 1945 CHI. PRABHA, A letter from Priyamvada is enclosed. I think you should join it2 Get yourself enrolled. About the work, we shall see after you have rested in the Ashram. -

Books on and by Shri Subhas Chandra Bose

Books on and by Shri Subhas Chandra Bose (Birth Anniversary on 23 January) (English Books) Sl. Title Author Publisher and Address Year of Books No. Publicati displayed on (#) 1. The Mission of Life Subhas Chandra Bose Thacker, Spink, Calcutta 1933 # 2. Subhash Bose and his Ideas Jagat S. Bright Indian Printing Works, Lahore 1946 # (Year added in Library 3. Netaji Speaks to the Nation Subhas Chandra Bose The Hero Publications, Lahore 1946 # (1928-1945) : A Symposium of Important Speeches and Writings of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose 4. Netaji Speaks: Being an S. Subuhey Padma Publications, Bombay 1946 # account of the Life and Achievements of Netaji 5. Important Speeches and Jagat S. Bright Indian Printing Works, Lahore 1947 Writings of Subhas Bose: Being a Collection of Most Significant Speeches, Writings and Letters of Subhas Bose from 1927 to 1945 6. The Hero of Hindustan Anthony Elenjimittam Orient Book Co., Calcutta 1947 # 7. Unto Him a Witness; The Story S.A. Aiyar Thacker, Bombay 1951 of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose in East Asia 8. Netaji Mystery Revealed S.M. Goswami The Author, Calcutta 1954 # 9. Netaji: A Realist and a Amita Ghosh The Author, Calcutta 1954 # Visionary 10. Verdict from Formosa: Gallant Harin Shah Atma Ram, Delhi 1956 # End of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose 11. Crossroads: Being the Works of Subhas Chandra Bose Asia Publishing House, Bombay 1962 # Subhas Chandra Bose, 1938- 1940 12. Selected speeches of Subhas India. Ministry of Publications Division, Ministry of 1962 # Chandra Bose Information and Information and Broadcasting, Broadcasting New Delhi 13. Netaji in Germany: A Little N.G.