Displaced Hindus After Partition in West Bengal1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Role of Bengali Women in the Freedom Movement Abstract

Heteroglossia: A Multidisciplinary Research Journal June 2016 | Vol. 01 | No. 01 Role of Bengali Women in the Freedom Movement Kasturi Roy Chatterjee1 Abstract In India women is always affected by the lack of opportunities and facilities. This is due to innate discrimination prevalent within the society for years. Thus when the role of Bengali women in the freedom movement is considered one faces a lot of difficulty, as because the women whatever their role were never highlighted. But in recent years however it is being pointed out that Bengali women not only participated in the freedom movement but had played an active role in it. KeyWords: Swadeshi, Boycott, catalysts, Patriarchy, Civil Disobidience, Satyagraha, Quit India. 1 Assistant Professor in History, Sundarban Mahavidyalaya, Kakdwip, South 24 Parganas, Pin-743347 49 Heteroglossia: A Multidisciplinary Research Journal June 2016 | Vol. 01 | No. 01 Introduction: In attempting to analyse the role of Bengali women in the Indian Freedom Struggle, one faces a series of problem is at the very outset. There are very few comprehensive studies on women’s participation in the freedom movement. In my paper I will try to bring forward a complete picture of Bengali women’s active role in the politics of protest: Bengal from 1905-1947, which is so far being discussed in different phases. In this way we can explain that how the women from time to time had strengthened the nationalist movement not only in the way it is shaped for them but once they participated they had mobilized the movement in their own way. Nature of Participatation in the Various Movements: A general idea for quite a long time had circulated regarding women’s participation that it is male dictated. -

Changing Wage Structure in India in the Post-Reform Era: 1993–2011 Hanan G

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Jacoby, Hanan G.; Dasgupta, Basab Article Changing wage structure in India in the post-reform era: 1993-2011 IZA Journal of Development and Migration Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Jacoby, Hanan G.; Dasgupta, Basab (2018) : Changing wage structure in India in the post-reform era: 1993-2011, IZA Journal of Development and Migration, ISSN 2520-1786, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 8, Iss. 8, pp. 1-26, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40176-017-0115-1 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/197467 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ www.econstor.eu Jacoby and Dasgupta IZA Journal of Development and Migration (2018) 8:8 IZA Journal of Development DOI 10.1186/s40176-017-0115-1 and Migration ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Changing wage structure in India in the post-reform era: 1993–2011 Hanan G. -

Chapter-I Historical Growth of Barasat Town

CHAPTER-I HISTORICAL GROWTH OF BARASAT TOWN INTRODUCTION: 'God made !the country and man made the town' - so says a proverb. Towns are created out of the necessities created by man also. For administrative reasons, for trade and commerce, and for many other obvious reasons, towns/cities emerge. Sometimes there are accidents of history (e.g. Calcutta), sometimes there are planning behind (e.g. Kalyani at Nadia District, West Bengal, Durgapur at Barddhaman District, West Bengal). The present investigation centres around a small township, which grew out of a tiny hamlet into a district town with all the characteristics associated with the process of urbanisation. The tiny hamlet expanded, attracted people from all around and developed into an administrative centre. Advantages of natural growth are no substitute for meticulous planning for tackling with the attendant problem of urbanisation. 1.1 PRE BRITISH PERIOD: The term 'Barasat' means 'Avenue'. Both sides of the road were planted with trees, Warren Hastings, the first Governor General of Bengal (1774-84), planted trees on both sides of the road. Pandit Haraprasad Shastri, a noted lndologist, was of the view that the name 'Barasat originated from the concept that on both sides of the road planted trees were in abundance. Other evidences are not lacking which prove that its history extends to the middle ages. Twelve members of the family of Jagat Sett, the banker of the Nawab of Bengal, lived here. Settpukur and other villages after their names are still there. Another Sett, Ramchandra, a descendant of Jagat Sett, dug out a tank near the Jessore Road to please Hastings. -

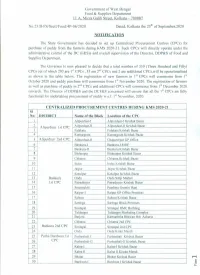

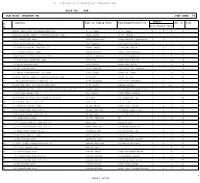

Notification on CPC.Pdf

Government of West Bengal Food & Supplies Department 11 A, Mirza Galib Street, Kolkata - 700087 No.2318-FS/Sectt/Food/4P-06/2020 Dated, Kolkata the zs" of September,2020 NOTIFICATION The State Government has decided to set up Centralized Procurement Centres (CPCs) for purchase of paddy from the farmers during KMS 2020-21. Such CPCs will directly operate under the administrative control of the DC (F&S)s and overall supervision of the Director, DDP&S of Food and Supplies Department. The Governor is now pleased to decide that a total number of 350 (Three Hundred and Fifty) nd CPCs out of which 293 are 1st CPCs ,55 are 2 CPCs and 2 are additional CPCs,will be operationalised as shown in the table below. The registration of new farmers in 1st CPCs will commence from 1sI October 2020 and paddy purchase will commence from 1st November 2020. The registration of farmers nd as well as purchase of paddy in 2 CPCs and additional CPCs will commence from 1st December 2020 onwards. The Director of DDP&S and the DCF&S concerned will ensure that all the 1st CPCs are fully functional for undertaking procurement of paddy w.e.f. 1st November, 2020. CENTRALIZED PROCUREMENT CENTRES DURING KMS 2020-21 SI No: DISTRICT Name ofthe Block Location of the CPC f--- 1 Alipurduar-I Alipurduar-I Krishak Bazar 2 Alipurduar-II Alipurduar-II Krishak Bazar f--- Alipurduar 1st CPC - 3 Falakata Falakata Krishak Bazar 4 Kurnarzram Kumarzram Krishak Bazar 5 Alipurduar 2nd Cf'C Alipurduar-Il Chaporerpar GP Office - 6 Bankura-l Bankura-I RlDF f--- 7 Bankura-II Bankura Krishak Bazar I--- 8 Bishnupur Bishnupur Krishak Bazar I--- 9 Chhatna Chhatna Krishak Bazar 10 - Indus Indus Krishak Bazar ..». -

Changing Meaning Of, , – Aboriginal Groups

INDEX Abhijat, – M. Monier-William’s views on, changing meaning of, , – negative assessments of, Aboriginal groups, Orientalist lineages of, , differentiation from ‘Aryan’ racial and sociological literati, connotations, , exclusion of, valour, , Academic Association, valour, in regional context of Adivasis, , , , –, Bengal, – –, virtual, , Hinduisation of, Asiatic Society, Aitihasik Chitra, and history-writing, agenda of, Atmiyata, and Indian history, – among unrelated individuals, and Rabindranath Tagore, as welding people of the samaj, circulation, , Anderson, Benedict, – Atmiya sajan, and role of print-capitalism, difference between role of print in Bagal, Jogeshchandra, European nationalism and in Bandyopadhyay, Krishnamohan, Bengal, Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar, Anglo-vernacular schools, and variations of caste rank in Aryan, Bengal, as culture, , and ‘low’ caste protest as race, movements, as racial categories, Bangiya Sahitya Parishat, Bengali-Aryan connection, , Romeshchandra Datta as its first , , –, chairman, Bengali-Hindu connection, , Bar Bhuiyans, , – , Basanta Ray, , colonial disjunction of, from Kedar Ray, , , non-Aryan groups, , Pratapaditya, , , , , dharma, differences from non-Aryan, Barth, Frederik difference from non-Aryan in and ethnic boundaries, Bengali discourse, Basu, Nagendranath, , , early samaj, , , and fieldwork undertaken to equated with ‘Hindu’, , reconstruct samajik itihas, idea, emphasis on kulagranthas, India, –, , , , – on caste, index on Dashinrarhiya Kayastha -

Dr. Sabyasachi Dasgupta Present Employment / Teaching Experience

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Sabyasachi Dasgupta Address for Communication Permanent Address Associate Professor C/O Aparajita Dasgupta Department of Forestry & Biodiversity A.K. Road [Opp. Western Club] Tripura University (A Central University) Ramnagar, Agartala Suryamaninagar, PIN-799022 Tripura- 799002 Tripura, INDIA Tel: +91 9410127024 (m) Email: [email protected] [email protected] Date of Birth : 9th December, 1974 Sex : Male Nationality : Indian I am working in the field of conservation ecology which always includes humans as a component. I work well as a team leader and I am known as active team member whenever given some assignment, I am very reliable and organized. Present Employment / Teaching Experience 13th November 2017 onwards Associate Professor in Department of Forestry and Biodiversity, Tripura University. Job responsibility: Teaching, Research, Consultancy and administration. 6th March 2007 to 10th November 2017 Assistant Professor in Department of Forestry, HNB Garhwal Central University. Teaching experience includes taking classes of Graduates and Post-Graduates of Forestry, Guiding Masters & Ph.D students. Administrative responsibilities include- Coordinating foreign collaboration, Resident tutor of Forestry Hostel, Member of IQAC task group for Research and Consultancy, Member of Departmental Purchase committee. Apart from these as a Coordinator, I am also looking after the consultancy related to Environmental Impact Assessment and Biodiversity management planning. 28th September, 2006 –28th February 2007 Assistant Professor, Agroforestry, in the College of Horticulture & Forestry, Central Agricultural University, Arunachal Pradesh, Govt. of India 13th August, 2005 – 20th September 20th 2006 Lecturer in Department of Forestry, HNB Garhwal University. 1 of 13 Qualifications May, 2007 Ph.D. in Ecology & Environment, Wildlife Institute of India, FRI University, Dehradun, Uttarkhand. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Name: Dr. SANKAR BOSE Mailing address (Office): Department of Geology Presidency University 86/1 College Street Kolkata 700 073 Tel: -91-33-22192636 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Web: http://www.presiuniv.ac.in/web/staff.php?staffid=104 Residence: Flat No. Q/6 Lake Gardens R.H.E. 48/4 Sultan Alam Road Kolkata 700 033 Telephone: +91-9874171661 (mobile) Date of Birth: June 07, 1968 Nationality: Indian Area of specialization: Metamorphic Petrology and Mineralogy Additional research interest Geochemistry and geochronology Current Status: Professor of Geology Educational qualification: Ph.D. in Science from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India in 2003. M.Sc. in Applied Geology from Jadavpur University, Kolkata in 1993 with 1st class (75% marks). B.Sc. with Geological Sciences (Hons.) from Jadavpur University, Kolkata in 1991 with 1st class (73% marks). Higher Secondary Examination (12th standard, WB Board) in 1987 with 1st division (75% marks). Secondary Examination (10th standard, WB Board) in 1985 with 1st division (79% marks). Academic Awards: o Awarded National Scholarship for the result of Secondary and B.Sc. Examination in 1985 and 1991 respectively. o Awarded Junior Research Fellowship by University Grants Commission, Government of India in 1993. o Awarded Post-Doctoral Fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) in 2006. o Awarded National Geoscience Award 2012 in the field of Basic Geoscience. o Awarded DST-JSPS Bilateral Research Fellowship for 2014-2016. 1 o Awarded JSPS Bridge Fellowship for the year 2016. Teaching experience: Worked as Lecturer in Geology in Durgapur Government College, Durgapur, India during the period July 1998 - January 2003 (UG and PG teaching) Worked as Lecturer in Geology in Presidency College, Kolkata, India during the January 2003 - December 2003 (UG and PG teaching) Worked as Senior Lecturer in Geology in Presidency College, Kolkata, India during the period December 2003 - December 2008 (UG and PG teaching). -

KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Ward No

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 088 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 MATHOR PARA ROAD 94 TALLYGUNGE ROAD A. P. HELA R. L. HELA 2 5 7 1 2 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE ABHA SARKAR SUSIL SARKAR 2 1 3 2 3 100 TALLYGUNGE ROAD ACHO CHAKHALIYA LATE KRISHNA CHAKHALIYA 2 4 6 3 4 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE ADAR MONDAL LATE MATHUN MONDAL 0 1 1 4 5 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE KOL 26 ADHIR GHOSH LT AKSHAY GHOSH 2 4 6 5 6 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE ADHIR MONDAL LATE DURGA MONDAL 1 0 1 6 7 19A PRATAP ADITYA PLACE KOL-26 ADHIR PRAMANICK LT UPEN PRAMANICK 3 2 5 7 8 11/1/M GOPAL BANERJEE LANE AJAY DAS LATE LALIT KR.DAS 2 2 4 8 9 13 BAULI MONDAL ROAD AJAY GHOSH LATE ANIL GHOSH 3 1 4 9 10 54 TALLYGUNGE ROAD AJAY SAMANTA LATE MITHILAL SAMANTA 2 2 4 10 11 37 NEPAL BHATTACHARYA 1ST LANE AJAY SINGH LATE LOK SINGH 3 1 4 11 12 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE AJIT DAS LT K. L. DAS 3 1 4 12 13 16A CHANDRA MONDAL LANE KOL-26 AJIT KARMAKAR LT SUDHIR KARMAKAR 4 3 7 14 14 TALLYGUNGE ROAD 108 TALLYGUNGE ROAD AJOY PRASD RAMDEB PRASAD 7 6 10+ 15 15 S.P. MUKHERJEE ROAD 200H S.P. MUKHERJEE ROAD KOL-26 ALAOK BOSE LT. -

Apr12 Cal Box

HAPPENINGS AT HABITAT WORLD IN April2012 6:00pm|PANEL DISCUSSION| 6:30am|IHC WALK|Walk through the 11:30am|IHC WALK|Art, Technology 7:15am|IHC WALK|Sair-o-Safar 1 Importance Of Blood Donation And The 8 flowering trees of Samadhi Gardens, 15 And New Media Akansha Rastogi, 6:30pm|DOC FILM|Divine Marriage 29 Safdarjang Madrasa: A Mid Summer Date Associate Curator at the Kiran Nadar 22 Second in a tetralogy of seasonal walks TALKS Role Of Youth by BloodConnect, IIT- WALK starting at Raj Ghat and going northwards WALK FILMS (English/2012/25mins) Dir.Benoy K. Museum of Art leads a walk exploring WALK that weaves in the warp and weft of Dilli's S Delhi & DU. Followed by street play- to Shanti Vana with Naturalist Pradip Behl The documentary is about the Krishen. Please contact the Programme select significant works from the new tarikh and tehzeeb, led by historian, Blood Donation: Karke Dekho, Achha Lagta Desk for registration and details. exhibition Crossings that plays on the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai pedagogue and 'Delhi'ologist Beeba Hai Dir.Snehil Basoya. Concludes with paradox of permanence and transience. Prod. Doordarshan WORKSHOP 10:30am- 5:00pm|WORKSHOP|Rare Sobti. Please contact the Programme Desk a musical performance by IIT Delhi Please contact the Programme Desk for 7:00pm|Raag Rang Santoor recital by for registration and details. Ragaas- Masterclass on Hindustani registration and details. MUSIC Students Collab: Green Shakti Classical music by Sarod Maestro Pt. Bipul Kumar Ray, disciple of Pt. 7:00pm|Bhajan by Gopa Bhattacharya. 7:00pm|Schools By Design A presentation MUSIC Foundation Buddhadev Dasgupta concludes. -

Dr Chandan Basu Is Currently Professor of History in the School of Social Sciences, Netaji Subhas Open University. He Is Also No

Dr Chandan Basu is currently Professor of History in the School of Social Sciences, Netaji Subhas Open University. He is also now the Director of the School of Social Sciences, NOSU. His areas of research are the development of left ideology and politics in West Bengal, the social history of modern Bengal and the gender studies. The Email ID of Dr Basu is [email protected]. Dr Basu’s publication details are given below: Publications Books 1. The Making of the Left Ideology in West Bengal: Culture, Political Economy, Revolution, 1947 – 1970. New Delhi: Abjjeet Publications, Delhi, 2009. (ISBN 978-93-80031-20-0) 2. Radical Ideology and ‘Controlled Politics’: CPI and the History of West Bengal, 1947-1964. Kolkata: Alphabet Books, 2015. (ISBN 978-81-929635-0-1) Edited Volume 1. Third Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Memorial Lecture (Decolonization and the Crisis of Hindu Nationalism, 1947-52: Sekhar Bandyopadhyay). Kolkata: Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Memorial Lecture, 2012. (Co-edited with Professor Debnarayan Modak) ISBN 978-93-82112-06-8 2. Fourth Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Memorial Lecture (The End Game of the Raj and Subhas Bose’s Political Strategy, 1943-1954: Sabyasachi Bhattacharya). Kolkata, 2013. (Co-edited with Professor Debnarayan Modak) ISBN 978-93-82112- 08-2 3. Gender Sensitization, Women Empowerment and Distance Education: History, Society and Culture. Kolkata: Netaji Subhas Open University, 2014. (Co-edited with Professor Kajal De and Sri Srideep Mukherjee) ISBN 978-93-82112-12-9 4. Fifth Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Memorial Lecture (Search for New Constituencies of Politics: Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Freedom Struggle: Bidyut Chakrabarty).