Concepts of Botany Spring 2009 Topic 10: Cyanobacteria & Algae A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riot and Dance ANSWER KEY2.Indd

REVIEW QUESTIONS ANSWER KEY 2 the riot and the dance teacher’s guide • answer key Chapter 1 10. Draw a water molecule (H2O) showing orbitals and shared electrons (atomic 1. A substance that has distinct chemical number of hydrogen: 1). properties and cannot be broken down into simpler substances by normal chemical means is a(n) element. 2. The smallest unit of an element is a(n) atom. 3. Two or more atoms bonded together is a(n) molecule. 4. A molecule containing two or more elements is a(n) compound. 5. The two subatomic particles contained in the nucleus of an atom are neutrons and protons. What are their charges? Neutral and positive. 6. The subatomic particles contained in the shells orbiting the nucleus are the electrons. Charge? Negative. 7. Atomic number is the number of protons in an atom. 11. A complete transfer of electrons from one 8. Atomic weight or mass number is the sum atom to another resulting in oppositely of protons and neutrons. charged atoms sticking together is called 9. Draw an oxygen atom (atomic number: 8). a(n) ionic bond. 12. When atoms are joined together because they are sharing electrons it is called a(n) covalent bond. 13. In a polar covalent bond how are the electrons being distributed in the molecule? The atoms with the greatest pull on the shared electrons will cause the electrons to swarm around them more than the weaker atoms. 14. In a non-polar covalent bond how are the electrons being distributed in the molecule? The atoms involved have an equal pull on the shared electrons and consequently the electrons are equally distributed between the two or more atoms. -

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes Green Algae or Chlorophyta Genus/Species Common Name Acrosiphonia coalita Green rope, Tangled weed Blidingia minima Blidingia minima var. vexata Dwarf sea hair Bryopsis corticulans Cladophora columbiana Green tuft alga Codium fragile subsp. californicum Sea staghorn Codium setchellii Smooth spongy cushion, Green spongy cushion Trentepohlia aurea Ulva californica Ulva fenestrata Sea lettuce Ulva intestinalis Sea hair, Sea lettuce, Gutweed, Grass kelp Ulva linza Ulva taeniata Urospora sp. Brown Algae or Ochrophyta Genus/Species Common Name Alaria marginata Ribbon kelp, Winged kelp Analipus japonicus Fir branch seaweed, Sea fir Coilodesme californica Dactylosiphon bullosus Desmarestia herbacea Desmarestia latifrons Egregia menziesii Feather boa Fucus distichus Bladderwrack, Rockweed Haplogloia andersonii Anderson's gooey brown Laminaria setchellii Southern stiff-stiped kelp Laminaria sinclairii Leathesia marina Sea cauliflower Melanosiphon intestinalis Twisted sea tubes Nereocystis luetkeana Bull kelp, Bullwhip kelp, Bladder wrack, Edible kelp, Ribbon kelp Pelvetiopsis limitata Petalonia fascia False kelp Petrospongium rugosum Phaeostrophion irregulare Sand-scoured false kelp Pterygophora californica Woody-stemmed kelp, Stalked kelp, Walking kelp Ralfsia sp. Silvetia compressa Rockweed Stephanocystis osmundacea Page 1 of 4 Red Algae or Rhodophyta Genus/Species Common Name Ahnfeltia fastigiata Bushy Ahnfelt's seaweed Ahnfeltiopsis linearis Anisocladella pacifica Bangia sp. Bossiella dichotoma Bossiella -

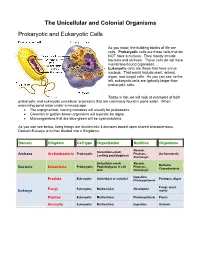

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic And

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells As you know, the building blocks of life are cells. Prokaryotic cells are those cells that do NOT have a nucleus. They mostly include bacteria and archaea. These cells do not have membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotic cells are those that have a true nucleus. That would include plant, animal, algae, and fungal cells. As you can see, to the left, eukaryotic cells are typically larger than prokaryotic cells. Today in lab, we will look at examples of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms that are commonly found in pond water. When examining pond water under a microscope… The unpigmented, moving microbes will usually be protozoans. Greenish or golden-brown organisms will typically be algae. Microorganisms that are blue-green will be cyanobacteria. As you can see below, living things are divided into 3 domains based upon shared characteristics. Domain Eukarya is further divided into 4 Kingdoms. Domain Kingdom Cell type Organization Nutrition Organisms Absorb, Unicellular-small; Prokaryotic Photsyn., Archaeacteria Archaea Archaebacteria Lacking peptidoglycan Chemosyn. Unicellular-small; Absorb, Bacteria, Prokaryotic Peptidoglycan in cell Photsyn., Bacteria Eubacteria Cyanobacteria wall Chemosyn. Ingestion, Eukaryotic Unicellular or colonial Protozoa, Algae Protista Photosynthesis Fungi, yeast, Fungi Eukaryotic Multicellular Absorption Eukarya molds Plantae Eukaryotic Multicellular Photosynthesis Plants Animalia Eukaryotic Multicellular Ingestion Animals Prokaryotic Organisms – the archaea, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and cyanobacteria Archaea - Microorganisms that resemble bacteria, but are different from them in certain aspects. Archaea cell walls do not include the macromolecule peptidoglycan, which is always found in the cell walls of bacteria. Archaea usually live in extreme, often very hot or salty environments, such as hot mineral springs or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. -

Coral Reef Algae

Coral Reef Algae Peggy Fong and Valerie J. Paul Abstract Benthic macroalgae, or “seaweeds,” are key mem- 1 Importance of Coral Reef Algae bers of coral reef communities that provide vital ecological functions such as stabilization of reef structure, production Coral reefs are one of the most diverse and productive eco- of tropical sands, nutrient retention and recycling, primary systems on the planet, forming heterogeneous habitats that production, and trophic support. Macroalgae of an astonish- serve as important sources of primary production within ing range of diversity, abundance, and morphological form provide these equally diverse ecological functions. Marine tropical marine environments (Odum and Odum 1955; macroalgae are a functional rather than phylogenetic group Connell 1978). Coral reefs are located along the coastlines of comprised of members from two Kingdoms and at least over 100 countries and provide a variety of ecosystem goods four major Phyla. Structurally, coral reef macroalgae range and services. Reefs serve as a major food source for many from simple chains of prokaryotic cells to upright vine-like developing nations, provide barriers to high wave action that rockweeds with complex internal structures analogous to buffer coastlines and beaches from erosion, and supply an vascular plants. There is abundant evidence that the his- important revenue base for local economies through fishing torical state of coral reef algal communities was dominance and recreational activities (Odgen 1997). by encrusting and turf-forming macroalgae, yet over the Benthic algae are key members of coral reef communities last few decades upright and more fleshy macroalgae have (Fig. 1) that provide vital ecological functions such as stabili- proliferated across all areas and zones of reefs with increas- zation of reef structure, production of tropical sands, nutrient ing frequency and abundance. -

A Comprehensive Kelp Phylogeny Sheds Light on the Evolution of an T Ecosystem ⁎ Samuel Starkoa,B,C, , Marybel Soto Gomeza, Hayley Darbya, Kyle W

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 136 (2019) 138–150 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A comprehensive kelp phylogeny sheds light on the evolution of an T ecosystem ⁎ Samuel Starkoa,b,c, , Marybel Soto Gomeza, Hayley Darbya, Kyle W. Demesd, Hiroshi Kawaie, Norishige Yotsukuraf, Sandra C. Lindstroma, Patrick J. Keelinga,d, Sean W. Grahama, Patrick T. Martonea,b,c a Department of Botany & Biodiversity Research Centre, The University of British Columbia, 6270 University Blvd., Vancouver V6T 1Z4, Canada b Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre, 100 Pachena Rd., Bamfield V0R 1B0, Canada c Hakai Institute, Heriot Bay, Quadra Island, Canada d Department of Zoology, The University of British Columbia, 6270 University Blvd., Vancouver V6T 1Z4, Canada e Department of Biology, Kobe University, Rokkodaicho 657-8501, Japan f Field Science Center for Northern Biosphere, Hokkaido University, Sapporo 060-0809, Japan ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Reconstructing phylogenetic topologies and divergence times is essential for inferring the timing of radiations, Adaptive radiation the appearance of adaptations, and the historical biogeography of key lineages. In temperate marine ecosystems, Speciation kelps (Laminariales) drive productivity and form essential habitat but an incomplete understanding of their Kelp phylogeny has limited our ability to infer their evolutionary origins and the spatial and temporal patterns of their Laminariales diversification. Here, we -

The Origin of Alternation of Generations in Land Plants

Theoriginof alternation of generations inlandplants: afocuson matrotrophy andhexose transport Linda K.E.Graham and LeeW .Wilcox Department of Botany,University of Wisconsin, 430Lincoln Drive, Madison,WI 53706, USA (lkgraham@facsta¡.wisc .edu ) Alifehistory involving alternation of two developmentally associated, multicellular generations (sporophyteand gametophyte) is anautapomorphy of embryophytes (bryophytes + vascularplants) . Microfossil dataindicate that Mid ^Late Ordovicianland plants possessed such alifecycle, and that the originof alternationof generationspreceded this date.Molecular phylogenetic data unambiguously relate charophyceangreen algae to the ancestryof monophyletic embryophytes, and identify bryophytes as early-divergentland plants. Comparison of reproduction in charophyceans and bryophytes suggests that the followingstages occurredduring evolutionary origin of embryophytic alternation of generations: (i) originof oogamy;(ii) retention ofeggsand zygotes on the parentalthallus; (iii) originof matrotrophy (regulatedtransfer ofnutritional and morphogenetic solutes fromparental cells tothe nextgeneration); (iv)origin of a multicellularsporophyte generation ;and(v) origin of non-£ agellate, walled spores. Oogamy,egg/zygoteretention andmatrotrophy characterize at least some moderncharophyceans, and arepostulated to represent pre-adaptativefeatures inherited byembryophytes from ancestral charophyceans.Matrotrophy is hypothesizedto have preceded originof the multicellularsporophytes of plants,and to represent acritical innovation.Molecular -

JUDD W.S. Et. Al. (2002) Plant Systematics: a Phylogenetic Approach. Chapter 7. an Overview of Green

UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS An Overview of Green Plant Phylogeny he word plant is commonly used to refer to any auto- trophic eukaryotic organism capable of converting light energy into chemical energy via the process of photosynthe- sis. More specifically, these organisms produce carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water in the presence of chlorophyll inside of organelles called chloroplasts. Sometimes the term plant is extended to include autotrophic prokaryotic forms, especially the (eu)bacterial lineage known as the cyanobacteria (or blue- green algae). Many traditional botany textbooks even include the fungi, which differ dramatically in being heterotrophic eukaryotic organisms that enzymatically break down living or dead organic material and then absorb the simpler products. Fungi appear to be more closely related to animals, another lineage of heterotrophs characterized by eating other organisms and digesting them inter- nally. In this chapter we first briefly discuss the origin and evolution of several separately evolved plant lineages, both to acquaint you with these important branches of the tree of life and to help put the green plant lineage in broad phylogenetic perspective. We then focus attention on the evolution of green plants, emphasizing sev- eral critical transitions. Specifically, we concentrate on the origins of land plants (embryophytes), of vascular plants (tracheophytes), of 1 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS 2 CHAPTER SEVEN seed plants (spermatophytes), and of flowering plants dons.” In some cases it is possible to abandon such (angiosperms). names entirely, but in others it is tempting to retain Although knowledge of fossil plants is critical to a them, either as common names for certain forms of orga- deep understanding of each of these shifts and some key nization (e.g., the “bryophytic” life cycle), or to refer to a fossils are mentioned, much of our discussion focuses on clade (e.g., applying “gymnosperms” to a hypothesized extant groups. -

Safety Assessment of Brown Algae-Derived Ingredients As Used in Cosmetics

Safety Assessment of Brown Algae-Derived Ingredients as Used in Cosmetics Status: Draft Report for Panel Review Release Date: August 29, 2018 Panel Meeting Date: September 24-25, 2018 The 2018 Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert Panel members are: Chair, Wilma F. Bergfeld, M.D., F.A.C.P.; Donald V. Belsito, M.D.; Ronald A. Hill, Ph.D.; Curtis D. Klaassen, Ph.D.; Daniel C. Liebler, Ph.D.; James G. Marks, Jr., M.D.; Ronald C. Shank, Ph.D.; Thomas J. Slaga, Ph.D.; and Paul W. Snyder, D.V.M., Ph.D. The CIR Executive Director is Bart Heldreth, Ph.D. This report was prepared by Lillian C. Becker, former Scientific Analyst/Writer and Priya Cherian, Scientific Analyst/Writer. © Cosmetic Ingredient Review 1620 L Street, NW, Suite 1200 ♢ Washington, DC 20036-4702 ♢ ph 202.331.0651 ♢ fax 202.331.0088 [email protected] Distributed for Comment Only -- Do Not Cite or Quote Commitment & Credibility since 1976 Memorandum To: CIR Expert Panel Members and Liaisons From: Priya Cherian, Scientific Analyst/Writer Date: August 29, 2018 Subject: Safety Assessment of Brown Algae as Used in Cosmetics Enclosed is the Draft Report of 83 brown algae-derived ingredients as used in cosmetics. (It is identified as broalg092018rep in this pdf.) This is the first time the Panel is reviewing this document. The ingredients in this review are extracts, powders, juices, or waters derived from one or multiple species of brown algae. Information received from the Personal Care Products Council (Council) are attached: • use concentration data of brown algae and algae-derived ingredients (broalg092018data1, broalg092018data2, broalg092018data3); • Information regarding hydrolyzed fucoidan extracted from Laminaria digitata has been included in the report. -

Cephaleuros Species, the Plant-Parasitic Green Algae

Plant Disease Aug. 2008 PD-43 Cephaleuros Species, the Plant-Parasitic Green Algae Scot C. Nelson Department of Plant and Environmental Protection Sciences ephaleuros species are filamentous green algae For information on other Cephaleuros species and and parasites of higher plants. In Hawai‘i, at least their diseases in our region, please refer to the technical twoC of horticultural importance are known: Cephaleu- report by Fred Brooks (in References). To see images of ros virescens and Cephaleuros parasiticus. Typically Cephaleuros minimus on noni in American Samoa, visit harmless, generally causing minor diseases character- the Hawai‘i Pest and Disease Image Gallery (www.ctahr. ized by negligible leaf spots, on certain crops in moist hawaii.edu/nelsons/Misc), and click on “noni.” environments these algal diseases can cause economic injury to plant leaves, fruits, and stems. C. virescens is The pathogen the most frequently reported algal pathogen of higher The disease is called algal leaf spot, algal fruit spot, and plants worldwide and has the broadest host range among green scurf; Cephaleuros infections on tea and coffee Cephaleuros species. Frequent rains and warm weather plants have been called “red rust.” These are aerophilic, are favorable conditions for these pathogens. For hosts, filamentous green algae. Although aerophilic and ter- poor plant nutrition, poor soil drainage, and stagnant air restrial, they require a film of water to complete their are predisposing factors to infection by the algae. life cycles. The genus Cephaleuros is a member of the Symptoms and crop damage can vary greatly depend- Trentepohliales and a unique order, Chlorophyta, which ing on the combination of Cephaleuros species, hosts and contains the photosynthetic organisms known as green environments. -

Photosynthesis... Using Algae Wrapped in Jelly Balls

Student Sheet 23 www.saps.org.uk Photosynthesis... using algae wrapped in jelly balls Algae can be considered as one-celled plants, and they usually live in water. You are going to use algae to look at the rate of photosynthesis. The algae are tiny and are difficult to work with directly in the water so the first part of the practical involves ‘immobilising’ the algae. This effectively traps large numbers of algal cells in ‘jelly like’ balls so that we can keep them in one place and not lose them. We use sodium alginate to help make the jelly. Sodium alginate is not harmful to the algae. When these algae are ‘wrapped up’ in the jelly balls they are excellent to use in experiments on photosynthesis. These algal balls are: • cheap to grow and easy to make – you will be able to make hundreds in a very short time • easy to get a standard quantity of plant material because each of the balls is approximately the same volume • easy to keep alive for several weeks so you can keep them for future experiments 1. First you need to obtain a 2. Now you have millions of algal 3. Finally we’re going to make the concentrated suspension of algae. cells in a small volume of liquid. balls… Do this by removing some of the It’s time to mix them into your liquid medium in which they are ‘jelly’. Pour the green mixture through growing in one of two ways. an open-ended syringe into a 2% Pour about 2.5cm3 of jelly (sodium solution of calcium chloride. -

CYANOBACTERIA (BLUE-GREEN ALGAE) BLOOMS When in Doubt, It’S Best to Keep Out!

Cyanobacteria Blooms FAQs CYANOBACTERIA (BLUE-GREEN ALGAE) BLOOMS When in doubt, it’s best to keep out! What are cyanobacteria? Cyanobacteria, also called blue-green algae, are microscopic organisms found naturally in all types of water. These single-celled organisms live in fresh, brackish (combined salt and fresh water), and marine water. These organisms use sunlight to make their own food. In warm, nutrient-rich (high in phosphorus and nitrogen) environments, cyanobacteria can multiply quickly, creating blooms that spread across the water’s surface. The blooms might become visible. How are cyanobacteria blooms formed? Cyanobacteria blooms form when cyanobacteria, which are normally found in the water, start to multiply very quickly. Blooms can form in warm, slow-moving waters that are rich in nutrients from sources such as fertilizer runoff or septic tank overflows. Cyanobacteria blooms need nutrients to survive. The blooms can form at any time, but most often form in late summer or early fall. What does a cyanobacteria bloom look like? You might or might not be able to see cyanobacteria blooms. They sometimes stay below the water’s surface, they sometimes float to the surface. Some cyanobacteria blooms can look like foam, scum, or mats, particularly when the wind blows them toward a shoreline. The blooms can be blue, bright green, brown, or red. Blooms sometimes look like paint floating on the water’s surface. As cyanobacteria in a bloom die, the water may smell bad, similar to rotting plants. Why are some cyanbacteria blooms harmful? Cyanobacteria blooms that harm people, animals, or the environment are called cyanobacteria harmful algal blooms. -

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual - pages 95-115) Major Characteristics Algae 1. Cbaracteristics 2. Classification 3. Division Cblorophyta 4. Division Chrysophyta 5. Division Phaeopbyta 6. Division Rhodopbyta Protozoans 1. Characteristics 2. Classification 3. Class FlageUata 4. Class Sarcodina 5. Class Ciliata 6. Class Sporozoa I Biology I Lecture Notes 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual- pages 95-115) Major Characteristics I. Protists possess eukaryotic cells with well defined nuclei and organelles 2. Most are unicellular, however there are multi-cellularforms 3. They are diverse in their structure 4. They vary in size from microscope algae to kelp that can be over 100feet in length 5. They are diverse (like bacteria) in the way they meet their nutritional needs A . Some are photosynthetic like land plants - are autotrophic B. Some ingest theirfood like animals - heterotrophic by ingestion C. Some absorb theirfood like bacteria andfungi - heterotrophic by absorption D. One species - Euglena - is mixotrophic meaning that it is capable ofboth autotrophic and heterotrophic life styles. 6. Reproduction in Protists A. is usually asexual by mitosis B. sexual reproduction involves meiosis and spore formation and usualJy occurs only when environmental conditions are hostile C. spores are resistant and can withstand adverse conditions 7. Some protozoans form cysts - a type ofresting stage 8. Photosynthetic protists (mostly algae) are part ofplankton. Plankton are those organisms suspended infresh and marine waters that serve asfood for -- heterotrophic animals and other protists 9. There are diverse opinions on how to classify members ofthe Kingdom Protista.