2018 Kerala Floods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Right to Information Act 2005 (Coir Board Manual)

COIR BOARD (Ministry of Agro & Rural Industries, Govt. of India) M.G.Road, P.B.No.1752, Cochin – 16. MANUALS (Under Clause IV(i) (b) of the RTI Act, 2005) (Published by) Coir Board, Coir House, P.B.No.1702, Kochi – 682 016. RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT, 2005 (RTI ACT, 2005) MANUALS (Under Clause IV(i) (b) of the RTI Act, 2005) H$`a ~moS>© COIR BOARD (H¥${f d J«m_rUmoÚmoJ _§Ìmb`, ^maV gaH$ma Ministry of Agro & Rural Industries, Govt. of India) nr ~r Z§ /P.B. No. 1752, E_ Or amoS>/ M.G. Road, H$moƒr/ Kochi-16 RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT, 2005 (RTI ACT, 2005) MANUAL NO. I Particulars of the Organization, Functions and Duties (Under Clause IV (i) of the RTI Act, 2005) Coir Board was set up by an Act of Parliament viz. the Coir Industry Act, 1953 (45 of 1953). The Act came into force w.e.f 9th February, 1954. Mission Our mission is to achieve self sustained development of Indian coir industry through strategic interventions, modernisation, research and development, technology upgradation, quality improvement, market promotion, human resource development, environment protection and welfare of all those who are engaged in the coir sector. Policy i) Coir Board – a facilitator and promoter * Coir Board shall play the role of a facilitator and promoter of coir industry in India. * Sectoral strength and expertise in key areas may be developed through greater participation of State Governments, local self-governments and progressive involvement of private sector including NGOs. ii) Fuller utilisation of raw-material * Enhanced utilisation of raw-material viz. -

Dam Break Analysis of Idukki Dam Using HEC RAS

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395 -0056 Volume: 04 Issue: 07 | July-2017 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Dam Break Analysis of Idukki Dam using HEC RAS Abhijith R1, Amrutha G2, Gopika Vijayaraj3, Rijisha T V4 1 Asst. Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Viswajyothi College of Engineering and Technology, Vazhakulam, Kerala, India 2,3,4 UG Scholar, Department of Civil Engineering, Viswajyothi College of Engineering and Technology, Vazhakulam, Kerala, India ---------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - Idukki reservoir, with an active capacity of developments, contingency evacuation planning and real 1459000000 m3 is a part of the Idukki Hydroelectric Project time flood forecasting. For assessing the flood damage due and comprises of Idukki Arch Dam, Kulamavu Dam and to dam breach it is necessary to predict not only the Cheruthoni dam. During the monsoon period when the dams possibility and mode of a dam failure, but also the flood hydrograph of discharge from the dam breach and the are full at its Maximum Reservoir Level (MRL) or in an propagation of the flood waves. The studies are to map or adverse event of dam break, the maximum discharge gets delineate areas of potential flood inundation resulting from released from these dams. This results into floods on a dam breach, flood depth, flow velocity and travel time of downstream and may cause disaster in cities or towns the flood waves etc. Knowledge of the flood wave and settled on the banks of the reservoir. This paper presents a flood-inundation area caused by a dam breach can case study of dam break analysis of Idukki Arch Dam using potentially mitigate loss of life and property damage. -

Revised Based on Discussions with Inter Ministerial Central Team

Revised based on discussions with Inter Ministerial Central Team Submitted by Additional Chief Secretary, Disaster Management (State Relief Commissioner) Government of Kerala 17 January 2018 1 Contents 1. Situation Assessment ................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Timeline of the incident as per IMD and INCOIS bulletin .................................................................. 3 1.3. Action taken by the State Government on 29-11-2017 to 30-11-2017 ............................................ 3 2. Losses ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Human Fatalities ................................................................................................................................ 7 2.2. Search and Rescue Operations .......................................................................................................... 8 2.3. Relief Assistance ................................................................................................................................ 8 2.4. Clearance of Affected Areas .............................................................................................................. 9 2.5. House damages ................................................................................................................................ -

GOVERNMENT of INDIA MINISTRY of EARTH SCIENCES LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION No

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF EARTH SCIENCES LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION No. 2710 TO BE ANSWERED ON WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 03, 2018 CYCLONE FORECAST 2710. SHRI K.C. VENUGOPAL: SHRI KONDA VISHWESHWAR REDDY: SHRI B. SRIRAMULU: SHRI TEJ PRATAP SINGH YADAV: SHRIMATI ANJU BALA: Will the Minister of EARTH SCIENCES be pleased to state: (a) whether the cyclone Ockhi has wrecked havoc across southern States resulting in loss of lives and properties and if so, the details thereof; (b) whether the precautionary communications to various State Governments including Kerala were issued on possible cyclone in Indian ocean and if so, the details thereof; (c) whether early warning system for sending cyclone alert has failed to reduce devastation caused by Ockhi cyclone and if so, the details thereof; (d) whether the Government has taken any new initiatives to bring in technological advancement in cyclone forecasting system and sending early warning to the affected States and communities including fishermen, if so, the details thereof including the international cooperation/agreement made/signed in this regard; and (e) the steps taken by the Government to develop state-of-the-art cyclone forecasting and management system in the country? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE FOR MINISTRY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY AND MINISTRY OF EARTH SCIENCES (SHRI Y. S. CHOWDARY) (a) Damage as on 27-12-2017 due to cyclone Ockhi is attached in Annexure-I. (b-c) Yes Madam. The cyclone Ockhi had rapid intensification during its genesis stage. The system emerged into the Comorin Area during night of 29th and intensified into Deep Depression in the early hrs of 30th and into Cyclonic Storm in the forenoon of 30th Nov. -

Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (Scsp) 2014-15

Government of Kerala SCHEDULED CASTE SUB PLAN (SCSP) 2014-15 M iiF P A DC D14980 Directorate of Scheduled Caste Development Department Thiruvananthapuram April 2014 Planng^ , noD- documentation CONTENTS Page No; 1 Preface 3 2 Introduction 4 3 Budget Estimates 2014-15 5 4 Schemes of Scheduled Caste Development Department 10 5 Schemes implementing through Public Works Department 17 6 Schemes implementing through Local Bodies 18 . 7 Schemes implementing through Rural Development 19 Department 8 Special Central Assistance to Scheduled C ^te Sub Plan 20 9 100% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 21 10 50% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 24 11 Budget Speech 2014-15 26 12 Governor’s Address 2014-15 27 13 SCP Allocation to Local Bodies - District-wise 28 14 Thiruvananthapuram 29 15 Kollam 31 16 Pathanamthitta 33 17 Alappuzha 35 18 Kottayam 37 19 Idukki 39 20 Emakulam 41 21 Thrissur 44 22 Palakkad 47 23 Malappuram 50 24 Kozhikode 53 25 Wayanad 55 24 Kaimur 56 25 Kasaragod 58 26 Scheduled Caste Development Directorate 60 27 District SC development Offices 61 PREFACE The Planning Commission had approved the State Plan of Kerala for an outlay of Rs. 20,000.00 Crore for the year 2014-15. From the total State Plan, an outlay of Rs 1962.00 Crore has been earmarked for Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP), which is in proportion to the percentage of Scheduled Castes to the total population of the State. As we all know, the Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP) is aimed at (a) Economic development through beneficiary oriented programs for raising their income and creating assets; (b) Schemes for infrastructure development through provision of drinking water supply, link roads, house-sites, housing etc. -

Post-Mortem of the Kerala Floods 2018 Tragedy

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT RESEARCH ISSN (Online) - 2691-5103 Volume 1, Issue 1 ISSN (Print) - 2693-4108 Post-mortem of the Kerala floods 2018 tragedy *Pritha Ghosh Abstract After more than two weeks of relentless rain, in early August, 2018, Kerala, often referred as 'God's own country' a State at the southern tip of India, known internationally for its scenic green landscapes, tourists spots and backwaters, is left with over 1 million people in relief camps and close to 400 reported dead- the number expected to be much higher as many areas remain inaccessible. The coastal strip wedged between the Arabian Sea and the Western Ghats mountain chain is prone to inundation. Unusually heavy monsoon rains have got the entire State of Kerala in the grip of a massive, unprecedented flood: the last time anything like this has happened was in 1924. Even before the rains, Kerala's economy presented a mixed picture: relatively higher per capita income, but slow growth and high unemployment rates. As torrential rains abated in Kerala, the major question confronting the State and its unfortunate citizens is an assessment of the colossal loss of property, agriculture and infrastructure and the focus has turned towards the short-term negative implications and how will it rebuild its economy. There were evidently many political, economic, social and managerial lessons to take away from the disaster. The paper will describe the magnitude of the disaster in Kerala and the impact on the human population. Keywords: Kerala floods, Political lessons, Economic lessons, Social lessons, Managerial lessons, Rebuild the economy 46 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT RESEARCH ISSN (Online) - 2691-5103 Volume 1, Issue 1 ISSN (Print) - 2693-4108 *Research Scholar, University of Engineering & Management , Kolkata 1. -

Hydro Electric Power Dams in Kerala and Environmental Consequences from Socio-Economic Perspectives

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY – SEPT 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Hydro Electric Power Dams in Kerala and Environmental Consequences from Socio-Economic Perspectives. Liji Samuel* & Dr. Prasad A. K.** *Research Scholar, Department of Economics, University of Kerala Kariavattom Campus P.O., Thiruvananthapuram. **Associate Professor, Department of Economics, University of Kerala Kariavattom Campus P.O., Thiruvananthapuram. Received: June 25, 2018 Accepted: August 11, 2018 ABSTRACT Energy has been a key instrument in the development scenario of mankind. Energy resources are obtained from environmental resources, and used in different economic sectors in carrying out various activities. Production of energy directly depletes the environmental resources, and indirectly pollutes the biosphere. In Kerala, electricity is mainly produced from hydelsources. Sometimeshydroelectric dams cause flash flood and landslides. This paper attempts to analyse the social and environmental consequences of hydroelectric dams in Kerala Keywords: dams, hydroelectricity, environment Introduction Electric power industry has grown, since its origin around hundred years ago, into one of the most important sectors of our economy. It provides infrastructure for economic life, and it is a basic and essential overhead capital for economic development. It would be impossible to plan production and marketing process in the industrial or agricultural sectors without the availability of reliable and flexible energy resources in the form of electricity. Indeed, electricity is a universally accepted yardstick to measure the level of economic development of a country. Higher the level of electricity consumption, higher would be the percapitaGDP. In Kerala, electricity production mainly depends upon hydel resources.One of the peculiar aspects of the State is the network of river system originating from the Western Ghats, although majority of them are short rapid ones with low discharges. -

Key Electoral Data of Kuttanad Assembly Constituency | Sample Book

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/KR-106-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5313-572-0 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 128 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-9 Constituency -(Lok Sabha) | Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-11 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Villages by Population -

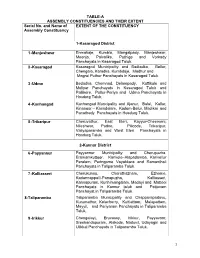

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

A Study About Post-Flood Impacts on Farmers of Wayanad District of Kerala

Print ISSN: 2277–7741 International Journal of Asian Economic Light (JAEL) SJIF Impact Factor(2018) : 6.028 Volume: 7 July-June 2019- 2020 A STUDY ABOUT POST-FLOOD IMPACTS ON FARMERS OF WAYANAD DISTRICT OF KERALA Dr. Joby Clement Department of Social Work, University of Mysore, Karnataka, India Dr. D. Srinivasa Guest Faculty, Department of Social Work, Sir M. V. PG. Centre of University of Mysore, Karnataka, India ABSTRACT From second week of August 2018 onwards the torrential rain and flooding damaged most of the districts of Kerala and caused the death of 483 civilians and many animals. That was the worst natural disaster to strike the southern Indian state in decades. Government of India declared it as level 3 type means “Severe” type calamity.13 Districts were severely affected with the consequences of flood among which Wayanad and Idukky had gone through several landslides along with flood and left isolated. This micro study focuses on the psycho social and economical aspects on farmers who faced the flood. The study also highlights to develop projects, strategies to mitigate losses now and in future. Both primary and secondary data were collected and analyzed the issue. This micro level study highlights the impacts of flood on society especially farmers. This study will help in framing the sustainable action plans in agriculture sector especially at rural villages to reduce the intensity of losses during calamities. KEYWORDS: Farmers, Flood, Stakeholders, Sustainable Action Plan, Micro Study BACKGROUND From first week of August 2018 onwards, Kerala State of Kerala, having a population around 3.3 Crore, is experienced the worst ever floods in its history since 1924. -

Munnar Landscape Project Kerala

MUNNAR LANDSCAPE PROJECT KERALA FIRST YEAR PROGRESS REPORT (DECEMBER 6, 2018 TO DECEMBER 6, 2019) SUBMITTED TO UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME INDIA Principal Investigator Dr. S. C. Joshi IFS (Retd.) KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD KOWDIAR P.O., THIRUVANANTHAPURAM - 695 003 HRML Project First Year Report- 1 CONTENTS 1. Acronyms 3 2. Executive Summary 5 3.Technical details 7 4. Introduction 8 5. PROJECT 1: 12 Documentation and compilation of existing information on various taxa (Flora and Fauna), and identification of critical gaps in knowledge in the GEF-Munnar landscape project area 5.1. Aim 12 5.2. Objectives 12 5.3. Methodology 13 5.4. Detailed Progress Report 14 a.Documentation of floristic diversity b.Documentation of faunistic diversity c.Commercially traded bio-resources 5.5. Conclusion 23 List of Tables 25 Table 1. Algal diversity in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 2. Lichen diversity in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 3. Bryophytes from the HRML study area, Kerala Table 4. Check list of medicinal plants in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 5. List of wild edible fruits in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 6. List of selected tradable bio-resources HRML study area, Kerala Table 7. Summary of progress report of the work status References 84 6. PROJECT 2: 85 6.1. Aim 85 6.2. Objectives 85 6.3. Methodology 86 6.4. Detailed Progress Report 87 HRML Project First Year Report- 2 6.4.1. Review of historical and cultural process and agents that induced change on the landscape 6.4.2. Documentation of Developmental history in Production sector 6.5. -

Film Tourism in India – a Beginning Towards Unlocking Its Potential

Film tourism in India – a beginning towards unlocking its potential FICCI Shoot at Site 2019 13 March 2019 Film tourism is a growing phenomenon worldwide, fueled by both the growth of the entertainment industry and the increase in international travel. Film tourism sector has seen tremendous growth in the past few years. It represents a gateway to new and more intense ways of experiencing destinations. At the same time, it creates the potential for new communities by way of an exchange of insights, knowledge and experience among the tourists themselves. Films play a significant role in the promotion of tourism in various countries and different states of India. A film tourist is attracted by the first-hand experience of the location captured on the silver screen. Not only is film tourism an excellent vehicle for destination marketing, it also presents new product development opportunities, such as location tours, film museums, exhibitions and the theme of existing tourist attractions with a film connection. This report focusses on the concept of film tourism and the various initiatives taken by both the state and central government of India for boosting film induced tourism through their respective film production policies. Dilip Chenoy Secretary General - Federation of Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry Foreword The significance of cinema in today’s times has gone beyond its intended purpose of mass entertainment. Cinema is a portal for people to escape from reality and into their world of fantasy. Cinema is a source of inspiration for some, a source of entertainment for some and a source of education for some.