Traditional Knowledge Rights and Wrongs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue 2013/2014 Curriculum Connections • New Shows • Theatrical Resources Hal Leonard Australia

Disney Aladdin KIDS Disney Cinderella KIDS Disney The Aristocats KIDS Disney The Jungle Book KIDS Disney Sleeping Beauty KIDS Winnie The Pooh KIDS Annie KIDS A Year with Frog and Toad KIDS Disney Aladdin JR. Disney Alice in Wonderland JR. Disney Beauty and the Beast JR. Disney High School Musical JR. Disney High School Musical 2 JR. Disney Mulan JR. Annie JR. Captain Louie JR. Dear Edwina JR. Fiddler on the Roof JR. Guys and Dolls JR. Honk! JR. Into the Woods JR. The Music Man JR. Once on This Island JR. The Phantom Tollbooth JR. The Pirates of Penzance JR. School House Rock Live! JR. Seussical JR. Millie JR. Disney Aladdin KIDS Disney Cinder- ella KIDS Disney The Aristocats KIDS Disney The Jungle Book KIDS Disney Sleeping Beauty KIDS Winnie The Pooh KIDS Annie KIDS A Year with Frog and Toad KIDS Disney Aladdin JR. Disney Alice in Wonderland JR. Disney Beauty and the Beast JR. Disney High School Musical JR. Disney High School Musical 2 JR. Disney Mulan JR. Annie JR. Captain Louie JR. Dear Edwina JR. Fiddler on the Roof JR. Guys and Dolls JR. Honk! JR. Into the Woods JR. The Music Man JR. Once on This Island JR. The Phantom Tollbooth JR. The Pirates of Penzance JR. School House Rock Live! JR. Seussical JR. Millie JR. Disney Aladdin KIDS Disney Cinderella KIDS Disney The Aristocats KIDS Disney The Jungle Book KIDS Disney Sleeping Beauty KIDS Winnie The Pooh KIDS Annie KIDS A Year with Frog and Toad KIDS Disney Aladdin JR. Disney Alice in Wonderland JR. -

THE ANCESTORS: the Ancestors Need to Be Strong Actor/Singers That Can Carry Solo Work

THE ANCESTORS: The Ancestors need to be strong actor/singers that can carry solo work. There are five ancestors: LAOZI (pronounced LAU-tsi) represents Honor and is the leader of the group. LIN represents Loyalty and is the hardest on Mulan; Lin does not appreciate any challenges to the oldworld belief system. ZHANG (ZANG) represents Strength, the strong silent type. HONG represents Destiny and is Laozi's right-hand man. YUN (YOON) represents Love and is Mulan's greatest advocate from the beginning – the mother figure that eventually encourages the others to support Mulan for who she is. All Ancestors may be cast as either male or female. Vocal Range: A3 – D5. Audition song: “Honor to Us All Part 2”. FA ZHOU (fa zoo): Mulan's father, requires a confident and calm performer who has a strong presence and can sing, at least a little. Without playing "older," his calm strength contrasts with Mulan's frenetic energy at the top of the show. Sings a brief solo. Vocal Range: C4 – D5. Audition song: Choose from any of the audition songs. FA LI: Mulan's mother, is someone who also possesses strength but understands her place in her generation and culture. There is a definite wisdom that she passes on to Mulan. Vocal Range: C4 – D5. Audition song: “Honor to Us All Part 2” or any of the other songs on the audition list. GRANDMOTHER FA: Grandmother sees greatness in Mulan, but still wants her to achieve it through tradition. Although she does not need to be a strong singer, an actor with mischief in her eye will work well here. -

Montuno Sadly Announces the Passing of One of Cuba's Finest

1931 - 2011 Montuno sadly announces the passing of one of Cuba’s finest guitarists, Manuel Galbán, who died on Thursday 7th July 2011, in Havana at 80 years old. At just 13 years old, he made his professional debut. He moved to Havana in 1956 where he worked with a number of bands and it was during this time that he began to make a name for himself within the Havana music scene. He joined the internationally acclaimed Los Zafiros in 1963, they combined the Cuban filín movement with other music styles such as bolero, doo-wop, calypso music, bossa nova and rock. This fusion transformed Los Zafiros into one of the most popular Cuban groups of the time and changed the course of Cuban music. They achieved international fame and performed at several venues in Europe including the Paris L’Olympia, a concert that was even attended by the Beatles. Galbán re- mained with the group for the majority of their career, becoming one of their key members. He was so important to the group’s success that the prominent Cuban pianist Peruchi once said of him: “You’d need two guitarists to replace Galbán”. From 1972 through 1975, Galbán led Cuba’s national music ensemble, Dirección Nacional de Música, before forming his own group Batey where he remained for 23 years. With Batey, Galbán toured the world and became one of the key ambassadors of Cuban music. During this period he recorded number of albums documenting popular Cuban music with the prestigious Cuban record label Egrem and the Bulgarian label Balkanton. -

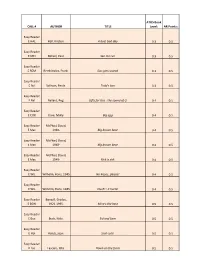

Title 10 Years Beautiful Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs More Than This

M & M MUSIC Title Title 10 Years 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Beautiful She Got It Wasteland 20 Fingers 10,000 Maniacs Short Dick Man More Than This 21st Century Girls Trouble Me 21st Century Girls 100 Proof Aged In Soul 2Play & Thomes Jules & Jucxi D Somebody's Been Sleeping Careless Whisper 10Cc 3 A M Donna Busted Dreadlock Holiday 3 Doors Down I'm Mandy Away From The Sun I'm Not In Love Be Like That Rubber Bullets Behind Those Eyes 112 Better Life It's Over Now Citizen Soldier Peaches & Cream Duck & Run Right Here For You Every Time You Go U Already Know Here By Me 112 & Ludacris Here Without You Hot & Wet It's Not My Time 12 Gauge Kryptonite Dunkie Butt Landing In London 12 Stones Let Me Be Myself We Are One Let Me Go 1910 Fruitgum Co Live For Today Simon Says Loser 2 Live Crew Road I'm On Doo Wah Diddy So I Need You Me So Horny When I'm Gone We Want Some P-Y When You're Young 2 Pac 3 Of A Kind California Love Baby Cakes Until The End Of Time Ikaw Ay Bayani 2 Pac & Eminem 3 Of Hearts One Day At A Time Love Is Enough 2 Pac & Notorious B.I.G. 30 Seconds To Mars Runnin (Dying To Live) Kill 2 Pistols & Ray J 311 You Know Me All Mixed Up Song List Generator® Printed 12/7/2012 Page 1 of 410 Licensed to Melissa Ben M & M MUSIC Title Title 311 411 Amber Teardrops Beyond The Grey Sky 44 Creatures (For A While) When Your Heart Stops Beating Don't Tread On Me 5 6 7 8 First Straw Steps Hey You 50 Cent Love Song 21 Questions 38 Special Amusement Park Caught Up In You Best Friend Fantasy Girl Candy Shop Hold On Loosely Disco Inferno If I'd Been -

COMPRO ORO Suburban Exotica

DESCRIPTION Compro Oro ; a psychedelic underground road trip to Africa, the Middle East and the Americas via Belgium. On the band's Suburban Exotica , the spirit of Cal Tjader , Mulatu Astatke , or Marc Ribot is never far away. One of the leading bands in the ever-expanding new wave of Belgian jazz, Compro Oro's wayward and psychedelic approach to a broad range of sounds has gained them a devoted fan base since the band's formation in 2014. Produced by Ghent-based multi-instrumentalist Dijf Sanders , Suburban Exotica digs deep into several ethnic music traditions, leaving the listener enthralled in dark grooves and rabid psychedelica. From the danceable beats and colorful sounds of "Miami New Wave", the exotic rhythms and textures of "10 Dollar Jeans Jacket", and the curious vibraphone infusions and wild guitar riffs of "Rastapopoulos", to the heady, bass-laden mover and shaker "Lalibela", and traditional Latin and Cuban rhythms of "Dark Crystal", Compro Oro offer wild, profound, and uncanny flavors that explore the best of Afro-Cuban music and jazz-tinged psychedelia. Suburban Exotica features drummer, keyboardist, and percussionist Joachim Cooder , son of guitar legend Ry Cooder who played on both the landmark Buena Vista Social Club albums and the Manuel Galban spin-off, Mambo Sinuendo . He adds percussion and his effects-laden electric mbira to three tracks on the album: "Miami New Wave", "Rastapopoulos", and "Dark Crystal". "I had a great time COMPRO ORO playing on this record. Compro Oro blends together so many interesting rhythms and styles that I never knew what was coming next. -

Character Breakdown Ancestors: 1

Character Breakdown Ancestors: 1. Laozi (pronounced LAU-tsi) represents honor and is the leader of the group. 2. Lin represents loyalty and is the hardest on Mulan; Lin does not appreciate any challenges to the old-world belief system. 3. Zhang represents strength, the strong silent type. 4. Hong represents destiny and is Laozi’s right-hand man. 5. Yun represents love and is Mulan’s greatest advocate from the beginning - the mother figure that eventually encourages the others to support Mulan for who she is. Gender: both • Vocal range top: D5 • Vocal range bottom: A3 Fa Zhou is Mulan’s father who is very strict and also a famed war veteran who was injured in war. Gender: male • Vocal range top: D5 • Vocal range bottom: C4 Fa Li is Mulan’s mother and is someone who also possesses strength, but understands her place in her generation and culture. Gender: female • Vocal range top: D5 • Vocal range bottom: C4 Grandmother Fa sees greatness in Mulan, but still wants her to achieve it through tradition. Gender: female • Vocal range top: D5 • Vocal range bottom: Bb3 Mulan is a young girl who is willing to give up her life to save her father. She enters the army as a man named Ping. She faces the worst enemy China has ever seen, the Hun leader Shan-Yu, who has an army willing to destroy anything in their path. In the army, Mulan discovers that she wants to be more than just someone’s daughter or wife. She is determined to prove that she too can be written in stone and give her family honor. -

B-Sides, Undercurrents and Overtones: Peripheries to Popular in Music, 1960 to the Present

B-Sides, Undercurrents and Overtones: Peripheries to Popular in Music, 1960 to the Present George Plasketes B-SIDES, UNDERCURRENTS AND OVERTONES: PERIPHERIES TO POPULAR IN MUSIC, 1960 TO THE PRESENT for Julie, Anaïs, and Rivers, heArt and soul B-Sides, Undercurrents and Overtones: Peripheries to Popular in Music, 1960 to the Present GEORGE PLASKETES Auburn University, USA © George Plasketes 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. George Plasketes has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington, VT 05401-4405 Surrey GU9 7PT USA England www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Plasketes, George B-sides, undercurrents and overtones : peripheries to popular in music, 1960 to the present. – (Ashgate popular and folk music series) 1. Popular music – United States – History and criticism I. Title 781.6’4’0973 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Plasketes, George. B-sides, undercurrents and overtones : peripheries to popular in music, 1960 to the present / George Plasketes. p. cm.—(Ashgate popular and folk music series) ISBN 978-0-7546-6561-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Popular music—United -

First Choice of Part Recommended Audition Piece

We are looking forward to some great auditions for Mulan Jr. in a couple of weeks! We would like to hear you sing at your audition in order to ensure that we match the correct individual with each role. It would be helpful if you could audition on the songs below. You may also choose to audition on another musical theater standard or Disney song of your choosing. If you choose to do so, please bring a recording of the accompaniment with you to your audition. If you do not want a solo or small ensemble vocal feature, you may choose to sing with a group or alone at an alternate time without other students present. No one will be required to sing alone if they are not comfortable with this. See the table below for specific song suggestions for each role. If the song on which you choose to audition is a duet or ensemble piece, please sing the melody for the entire piece even if your desired character does not sing all of the song. All students will be considered for all roles regardless of the song on which they audition. Students auditioning for the role of Mulan should prepare the excerpts provided for BOTH songs listed below; we may or may not need to hear both. Click on the links to listen to and practice the piece that you choose to sing. You may audition with the guide vocals IF NECESSARY. However, singing with only the accompaniment demonstrates a higher level of musicianship AND preparation. Please contact Mrs. -

Manuel Galbán

Manuel Galbán Manuel Galbán nace en 1931 en Gibara, en la provincia de Holguín (Cuba), en el seno de una familia profundamente vinculada a la música, ya que dos de sus hermanos tocaban la guitarra, su padre tocaba el tres y su madre cantaba. Su educación musical, fundamentalmente autodidacta, se inició muy pronto, “cuando, sentado en un taburete, todavía no me llegaban los pies al suelo”, contaba Manuel Galbán, y ya desde un primer momento fue alternando la guitarra con el tres en distintas formaciones locales. Su debut profesional se produce en 1944, con la Orquesta Villa Blanca. En 1956, Galbán se traslada a La Habana. Durante los siguientes siete años, el guitarrista alternará las actuaciones en diferentes locales de la capital con las apariciones en emisiones radiofónicas y la participación en distintos trabajos discográficos. Estos años son fundamentales en la carrera de Galbán, pues es cuando se da a conocer en la escena musical cubana, que descubre el fraseo que lo hará famoso y ese sonido que sólo él ha sabido extraer de la guitarra. No en vano, Galbán será uno de los primeros guitarristas de la historia en emplear habitualmente la mano derecha para mutear el sonido de las cuerdas y extraer unos tonos secos de su instrumento, unos tonos que acercan la sonoridad de la guitarra a la de un instrumento de percusión. Al mismo tiempo, su interés por la música norteamericana le lleva a explorar también los sonidos que unos años más tarde se harán populares en la música de inspiración surfera y a incorporarlos a su estilo. -

Master List for AR Revised

ATOS Book CALL # AUTHOR TITLE Level: AR Points: Easy Reader E HAL Hall, Kirsten. A bad, bad day 0.3 0.5 Easy Reader E MEI Meisel, Paul. See me run 0.3 0.5 Easy Reader E REM Remkiewicz, Frank. Gus gets scared 0.3 0.5 Easy Reader E Sul Sullivan, Paula. Todd's box 0.3 0.5 Easy Reader E Bal Ballard, Peg. Gifts for Gus : the sound of G 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader E COX Coxe, Molly. Big egg 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader McPhail, David, E Mac 1940- Big brown bear 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader McPhail, David, E Mac 1940- Big brown bear 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader McPhail, David, E Mac 1940- Rick is sick 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader E WIL Wilhelm, Hans, 1945- No kisses, please! 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader E WIL Wilhelm, Hans, 1945- Ouch! : it hurts! 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader Bonsall, Crosby, E BON 1921-1995. Mine's the best 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Buc Buck, Nola. Sid and Sam 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Hol Holub, Joan. Scat cats! 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Las Lascaro, Rita. Down on the farm 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Mor Moran, Alex. Popcorn 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Tri Trimble, Patti. What day is it? 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Wei Weiss, Ellen, 1949- Twins in the park 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Kli Amoroso, Cynthia. -

Disney's Mulan

Aud number_______ Height _______ Theatre Company Audition Form – Disney’s Mulan, Jr. Please fill out this form completely and clearly and bring it to the auditions. Who may audition: Any Tulare County Student, grades 1 – 12 Date & Time: Thursday, June 2, 2011 and Friday , June 3, 2011 @ 4:00 p.m. Callbacks (by invitation only) Saturday, June 4, 2011 @ 9:00 a.m. Location: TCOE, 7000 Doe Avenue, Visalia (Doe & Shirk), Sequoia Roo m IMPORTANT OPPORTUNITY: to understand our program better and/or be extra prepared for auditions, come to an audition preparation workshop on Tuesday , May 24, 2011 @ 5:30 p.m . in the Elderwood Room, 7000 Doe Avenue , Visalia. You will be able to meet the directors, check out a copy of the show script and a music CD, ask questions and become acquainted with our audition process. Parents and students are encouraged to attend. Call Charlotte at 651- 1482 ext 3646 or email her [email protected] with any questions. This meeting is not mandatory but will really help you! This is a “cattle-call” style audition where everyone will sing the same piece of music and speak the same dialogue. Have this memorized to be sure to give your best audition: Vocal audition Speaking audition We w ake up each morning to another day MUSHU( pleading ): I just want my chance to earn my way back Each one playing a part that is her own into the Temple- this is where I belong. Let me help Mulan. With a future as certain as the buds of May (grateful & excited ) Wow! Thank you! This just proves how Every step of the way already know much you believe in me! Written in Stone ** Wear clothing suitable for a dance audition (taught to you that day). -

The Continuo Arts Foundation's

The Continuo Arts Foundation’s Summer Musical Theater Conservatory Presents: Saturday, July 26th, 2014 4:00 p.m. Matinee * 7:30 p.m. Evening Hinman Hall, St. John’s Lutheran Church 587 Springfield Avenue Summit, NJ 07901 Staff & Volunteer Staff Samantha Holgate............................................................................SMTC Director Candace Wicke............................................................................Executive Director Jocelyn McGillian......................................................................Executive Assistant Lyle Brehm..........................................................................Development Associate Emmy Abdill, Julia Craig....................................................Administrative Interns Prestine Allen, Jose Soto..................................................................................Sound Dan Apruzzese, Craig Kovera...................................................Production Chairs Petra Krugel...................................................................................Costume Mistress Gloria Ron-Fornes, Eileen Blancato........................................Concession Chairs Join us between shows for David Scherzer.....................................................................................Videographer Gary McCready....................................................................................Photographer dinner at the Grand Summit Board of Directors Hotel’s award winning Candace Wicke Heidi Evenson Joe Ciresi William Hildebrant Jesse