Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Action Is Funded by the European Union

EN This action is funded by the European Union ANNEX 7 of the Commission Decision on the financing of the Annual Action Programme 2018 – part 3 in favour of Eastern and Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean to be financed from the 11th European Development Fund Action Document for Somalia Regional Corridors Infrastructure Programme (SRCIP) 1. Title/basic act/ Somalia Regional Corridors Infrastructure Programme (SRCIP) CRIS number RSO/FED/040-766 financed under the 11th European Development Fund (EDF) 2. Zone East Africa, Somalia benefiting from The action shall be carried out in Somalia, in the following Federal the Member States (FMS): Galmudug, Hirshabelle, Jubaland, Puntland action/location 3. Programming 11th EDF – Regional Indicative Programme (RIP) for Eastern Africa, document Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean (EA-SA-IO) 2014-2020 4. Sector of Regional economic integration DEV. Aid: YES1 concentration/ thematic area 5. Amounts Total estimated cost: EUR 59 748 500 concerned Total amount of EDF contribution: EUR 42 000 000 This action is co-financed in joint co-financing by: Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) for an amount of EUR 3 500 000 African Development Fund (ADF) 14 Transitional Support Facility (TSF) Pillar 1: EUR 12 309 500 New Partnership for Africa's Development Infrastructure Project Preparation Facility (NEPAD-IPPF): EUR 1 939 000 6. Aid Project Modality modality(ies) Indirect management with the African Development Bank (AfDB). and implementation modality(ies) 7 a) DAC code(s) 21010 (Transport Policy and Administrative Management) - 8% 21020 (Road Transport) - 91% b) Main 46002 – African Development Bank (AfDB) Delivery Channel 1 Official Development Aid is administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective. -

Rethinking the Somali State

Rethinking the Somali State MPP Professional Paper In Partial Fulfillment of the Master of Public Policy Degree Requirements The Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs The University of Minnesota Aman H.D. Obsiye May 2017 Signature below of Paper Supervisor certifies successful completion of oral presentation and completion of final written version: _________________________________ ____________________ ___________________ Dr. Mary Curtin, Diplomat in Residence Date, oral presentation Date, paper completion Paper Supervisor ________________________________________ ___________________ Steven Andreasen, Lecturer Date Second Committee Member Signature of Second Committee Member, certifying successful completion of professional paper Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 5 The Somali Clan System .......................................................................................................... 6 The Colonial Era ..................................................................................................................... 9 British Somaliland Protectorate ................................................................................................. 9 Somalia Italiana and the United Nations Trusteeship .............................................................. 14 Colonial -

Somalia Hunger Crisis Response.Indd

WORLD VISION SOMALIA HUNGER RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT 5 March 2017 RESPONSE HIGHLIGHTS 17,784 people received primary health care 66,256 people provided with KEY MESSAGES 24,150,700 litres of safe drinking water • Drought has led to increased displacement education. In Somaliland more than 118 of people in Somalia. In February 2017 schools were closed as a result of the alone, UNHCR estimates that up to looming famine. 121,000 people were displaced. • Urgent action at this stage has a high • There is a sharp increase in the number of chance of saving over 300,000 children Acute Water Diarrhoea (AWD/cholera) who are acutely malnourished as well cases. From January to March, 875 AWD as over 6 million people facing possible cases and 78 deaths were recorded in starvation across the country. 22,644 Puntland, Somaliland and Jubaland. • Despite encouraging donor contributions, • There is an urgent need to scale up the Somalia humanitarian operational people provided with support for health interventions in the plan is less than 20% funded (UNOCHA, South West State (SWS) especially FTS, 7th March 2017). Approximately 5,917 in districts that have been hard hit by US$825 million is required to reach 5.5 NFI kits outbreaks of Acute Watery Diarrhoea million Somalis facing possible famine until (AWD). Only few agencies have funding June 2017. to support access to health care services. • More than 6 million people or over 50% • According to Somaliland MOH, high of Somalia’s population remain in crisis cases of measles, diarrhea and pneumonia and face possible famine if aid does not have been reported since November as match the scale of need between now main health complications caused by the and June 2017. -

Peace in Puntland: Mapping the Progress Democratization, Decentralization, and Security and Rule of Law

Peace in Puntland: Mapping the Progress Democratization, Decentralization, and Security and Rule of Law Pillars of Peace Somali Programme Garowe, November 2015 Acknowledgment This Report was prepared by the Puntland Development Re- search Center (PDRC) and the Interpeace Regional Office for Eastern and Central Africa. Lead Researchers Research Coordinator: Ali Farah Ali Security and Rule of Law Pillar: Ahmed Osman Adan Democratization Pillar: Mohamoud Ali Said, Hassan Aden Mo- hamed Decentralization Pillar: Amina Mohamed Abdulkadir Audio and Video Unit: Muctar Mohamed Hersi Research Advisor Abdirahman Osman Raghe Editorial Support Peter W. Mackenzie, Peter Nordstrom, Jessamy Garver- Affeldt, Jesse Kariuki and Claire Elder Design and Layout David Müller Printer Kul Graphics Ltd Front cover photo: Swearing-in of Galkayo Local Council. Back cover photo: Mother of slain victim reaffirms her com- mittment to peace and rejection of revenge killings at MAVU film forum in Herojalle. ISBN: 978-9966-1665-7-9 Copyright: Puntland Development Research Center (PDRC) Published: November 2015 This report was produced by the Puntland Development Re- search Center (PDRC) with the support of Interpeace and represents exclusively their own views. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the contribut- ing donors and should not be relied upon as a statement of the contributing donors or their services. The contributing donors do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor do they accept responsibility for any use -

Factors Influencing Persisted High Global Acute Malnutrition Among IDP Camps in Puntland

UNICEF Field Office NEZ Factors Influencing Persisted High Global Acute Malnutrition Among IDP Camps in Puntland Rapid Assessment of IDP settlements of Bosaso, Garowe, Galkayo and Gardo, April 2018 ABBREVIATIONS ANC antenatal Care ARI Acute Respiratory Infections AWD Acute Watery Diarrhea C4D Communication for Development CBO Community Based Organizations CHW Community Health workers EPI Expended Program on Immunization FCS Food Consumption Scores FSNAU Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit GAM global Acute Malnutrition HHS Household Hunger Scores IDPs Internally Displaced peoples IEC Information Education Communication ISDP Integrated Services for Displaced Persons IYCF Infant and Young Child Feeding MCHN Maternal and Child Health and Nutrition MDM Medicins De Monde MOH Ministry of Health MSF Medecins Sans Frontieres MUAC Mid Upper Arm circumference NGOs Non-Governmental Organizations NUWACO Nugal Water Company OPD Outpatient Department ORS Oral Rehydration Salt OTP Outpatient therapeutic Program I PNC Postnatal Care PSA Puntland Students Association RI Relief International RR Risk Ratio SAM Severe Acute malnutrition SC Stabilization Center SCI Copying Strategies Index SDRA Social Development and Research Association SIAs supplementary Immunization Activities SRCS Somali Red Crescent society TSFP Targeted Supplementary Feeding Program UNICEF: United Nations Children’s Fund WFP World Food Program WHO World Health Organization WVI World Vision II TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................ -

Galkayo Urban Baseline Profile

L I V E L I H OLivelihood O D Baseline Profile - Galkayo Urban FSNAU BASELINE Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit - Somalia P R O F I L E Issued October, 2010 Galkayo Urban HISTORICAL TIMELINE GALKAYO AND SURROUNDING LiVELIHOOD ZONES GALKAYO HISTORICAL TIMELINE 2005-2009 Food DJIBOUTI Awdal Sanag Year Security Events, Effects, and Reponses Woq. Galbeed Bari Ranking Togdheer Sool Below Average Year: Prolonged Nugal drought; influx of IDPs; decline of food prices; influx of destitute pastoralists; Jariban Mudug Goldogob Galgadud political problems in southern Galkayo Bakol Galkayo Hiran (split of Galmudug); Improved security GAALKACYO Gedo 2009 2 situation compared to previous M. Shabelle Bay conflicts between the North and Banadir L. Shabelle South Galkayo, despite of organized Juba and targeted killings in the reference year.; replacement of CARE by WFP and 50% reduction of food aid. Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit - Somalia http://www.fsnau.org P.O. Box 1230 Village Market, Nairobi, Kenya Email: [email protected] tel: 254-20-4000000 fax:254-20-4000555 FSNAU is managed by FAO The boundaries and names on these maps do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Below Average Year: Drought; The regional & District boundaries reflect those endorsed by the Government of the Republic of Somalia in 1986. insecurity/piracy; inflation; food aid; influx of rural destitute and Hobyo 2008 2 ensuing tensions; suspension of CARE activities; lifting of roadblocks; establishment of IRC office in Galkayo; high food prices. Bad Year: Drought; inflation; insecurity; IDPs influx; water shortage and water trucking from Addun Pastoral: Mixed sheep & goats, camel 2007 2 Belet Weyne; high water price; Awdal border & coastal towns: Petty trading, fishing, salt mining printing of Somali bank note; poor purchasing power; expansion of Central regions Agro-Pastoral: Cowpea, sheep & goats, camel, cattle town; and increased social services. -

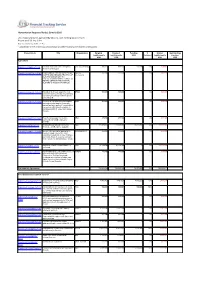

With Funding Status of Each Report As

Humanitarian Response Plan(s): Somalia 2016 List of appeal projects (grouped by Cluster), with funding status of each Report as of 23-Sep-2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R3) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and recipient organizations. Project Code Title Organization Original Revised Funding % Unmet Outstanding requirements requirements USD Covered requirements pledges USD USD USD USD Agriculture SOM-16/A/84942/5110 Puntland and Lower Juba Emergency VSF (Switzerland) 998,222 998,222 588,380 59% 409,842 0 Animal Health Support SOM-16/A/86501/15092 PROVISION OF FISHING INPUTS FOR SAFUK- 352,409 352,409 0 0% 352,409 0 YOUTHS AND MEN AND TRAINING OF International MEN AND WOMEN ON FISH PRODUCTION AND MAINTENANCE OF FISHING GEARS IN THE COASTAL REGIONS OF MUDUG IN SOMALIA. SOM-16/A/86701/14592 Integrated livelihoods support to most BRDO 500,000 500,000 0 0% 500,000 0 vulnerable conflict affected 2850 farming and fishing households in Marka district Lower Shabelle. SOM-16/A/86746/14852 Provision of essential livelihood support HOD 500,000 500,000 0 0% 500,000 0 and resilience building for Vulnerable pastoral and agro pastoral households in emergency, crisis and stress phase in Kismaayo district of Lower Juba region, Somalia SOM-16/A/86775/17412 Food Security support for destitute NRO 499,900 499,900 0 0% 499,900 0 communities in Middle and Lower Shabelle SOM-16/A/87833/123 Building Household and Community FAO 111,805,090 111,805,090 15,981,708 14% 95,823,382 0 Resilience and Response Capacity SOM-16/A/88141/17597 Access to live-saving for population in SHARDO Relief 494,554 494,554 0 0% 494,554 0 emergency and crises of the most vulnerable households in lower Shabelle and middle Shabelle regions, and build their resilience to withstand future shocks. -

THE PUNTLAND STATE of SOMALIA 2 May 2010

THE PUNTLAND STATE OF SOMALIA A TENTATIVE SOCIAL ANALYSIS May 2010 Any undertaking like this one is fraught with at least two types of difficulties. The author may simply get some things wrong; misinterpret or misrepresent complex situations. Secondly, the author may fail in providing a sense of the generality of events he describes, thus failing to position single events within the tendencies, they belong to. Roland Marchal Senior Research Fellow at the CNRS/ Sciences Po Paris 1 CONTENT Map 1: Somalia p. 03 Map 02: the Puntland State p. 04 Map 03: the political situation in Somalia p. 04 Map 04: Clan division p. 05 Terms of reference p. 07 Executive summary p. 10 Recommendations p. 13 Societal/Clan dynamics: 1. A short clan history p. 14 2. Puntland as a State building trajectory p. 15 3. The ambivalence of the business class p. 18 Islamism in Puntland 1. A rich Islamic tradition p. 21 2. The civil war p. 22 3. After 9/11 p. 23 Relations with Somaliland and Central Somalia 1. The straddling strategy between Somaliland and Puntland p. 26 2. The Maakhir / Puntland controversy p. 27 3. The Galmudug neighbourhood p. 28 4. The Mogadishu anchored TFG and the case for federalism p. 29 Security issues 1. Piracy p. 31 2. Bombings and targeted killings p. 33 3. Who is responsible? p. 34 4. Remarks about the Puntland Security apparatus p. 35 Annexes Annex 1 p. 37 Annex 2 p. 38 Nota Bene: as far as possible, the Somali spelling has been respected except for “x” replaced here by a simple “h”. -

MALI Somalia

Somalia: Travel Advice ERITREA YEMEN n ‘Abd al Kūrī A d e (YEMEN) o f Caluula DJIBOUTI u l f DJIBOUTI G Saylac Laasqoray Boosaaso Maydh Ceerigaabo Badhan Baki Berbera Bown Xaafuun Boorama SOMALILAND PUNTLAND Burco Bandarbeyla Hargeysa Bandar Wanaag Garadag Qardho Oodweyne Xudun A Laascaanood Sinujiif Buuhoodle Garoowe I Eyl Jirriiban ETHIOPIA N Gaalkacyo L (Galkayo) Gellinsoor Cadaado (Adado) A (Galmudug interim administration centre) Godinlabe A Dhuusamareeb E Hobyo GALMUDUG Xarardheere Beledweyne (Haradhere) C W e Yeed b i S Maxaas h M a b Xuddur e Derri e l le O Luuq Tayeeglow Waajid Buulobarde W Mereeg e b i HIRSHABELLE J u b Baydhabo Garbahaarrey b O a (Baidoa) Mahaddayweyne Qansaxdheere El Wak El Beru Hagia International Boundary Buurhakaba Wanlaweyn Jawhar N Cadale Administrative Boundary Baardheere Diinsoor S National Capital SOUTH WEST Afgooye STATE A Administrative Centre MUQDISHO Dhoomadheere (MOGADISHU) City / Town Marka JUBALAND I Major Road Bu'aale Rail Haaway Baraawe 0 100miles D 0 100 200 kilometres Jilib Bilis Qooqaani Kamsuuma N Advise against all travel I Kismaayo Advise against all but essential travel KENYA Buur Gaabo Federal Member States established, though issues of formalisation still pending. (Bur Gavo) Somaliland claims independence but is not internationally recognised* Areas of Sool and Sanaag are claimed by both Puntland and Somaliland. Galmudug and Puntland both claim parts of Galkayo. FCDO (TA) 035 Edition 1 (September 2020) Please note Briefing Maps are not to taken as necessarily representing the views of the UK government on boundaries or political status. This map has been designed for briefing purposes only and should not be used for determining the precise location of places or features, or considered an authority on the delimitation of international boundaries or on the spelling of place and feature names. -

Understanding US Policy in Somalia Current Challenges and Future Options Contents

Research Paper Paul D. Williams Africa Programme | July 2020 Understanding US Policy in Somalia Current Challenges and Future Options Contents Summary 2 1 Introduction 3 2 What Is the US Mission in Somalia? 7 3 How Is the US Implementing Its Mission in Somalia? 10 4 Is US Policy Working in Somalia? 15 5 What Future for US Engagement in Somalia? 21 About the Author 24 Acknowledgments 24 1 | Chatham House Understanding US Policy in Somalia Summary • The US has real but limited national security interests in stabilizing Somalia. Since 2006, Washington’s principal focus with regard to Somalia has been on reducing the threat posed by al-Shabaab, an Al-Qaeda-affiliated Islamist insurgent group seeking to overthrow the federal government. • Successive US administrations have used military and political means to achieve this objective. Militarily, the US has provided training, equipment and funds to an African Union operation, lent bilateral support to Somalia’s neighbours, helped build elements of the reconstituted Somali National Army (SNA), and conducted military operations, most frequently in the form of airstrikes. Politically, Washington has tried to enable the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) to provide its own security, while implementing diplomatic, humanitarian and development efforts in parallel. • Most US resources have gone into its military efforts, but these have delivered only operational and tactical successes without altering the strategic terrain. The war against al-Shabaab has become a war of attrition. Effectively at a stalemate since at least 2016, neither side is likely to achieve a decisive military victory. • Instead of intensifying airstrikes or simply disengaging, the US will need to put its diplomatic weight into securing two linked negotiated settlements in Somalia. -

Transition Initiatives for Stabilization Plus (Tis+) Program Year Three – Annual Work Plan

TRANSITION INITIATIVES FOR STABILIZATION PLUS (TIS+) PROGRAM YEAR THREE – ANNUAL WORK PLAN (OCTOBER 1, 2017 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2018) Revised November 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by AECOM. Annual Work plan | Transition Initiatives for Stabilization Plus (TIS+) Program i TRANSITION INITIATIVES FOR STABILIZATION PLUS (TIS+) PROGRAM YEAR THREE – ANNUAL WORK PLAN (OCTOBER 1, 2017 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2018) Contract No: AID-623-C-15-00001 Submitted to: USAID | Somalia Prepared by: AECOM International Development DISCLAIMER: The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Year Three - Annual Work Plan | Transition Initiatives for Stabilization Plus (TIS+) Program i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................ ii Acronym List .............................................................................................................................................. iii Stabilization Context .................................................................................................................................. 5 Goals and Objectives of USAID and TIS+ ............................................................................................... 6 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ -

The Somali Shelter / NFI Cluster

The Somali Shelter / NFI Cluster Reviews of coordination and response Combined report April 2015 Disclaimer The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR. Responsibility for the opinions expressed in this report rests solely with the authors. Publication of this document does not imply endorsement by UNHCR of the opinions expressed. Somalia Shelter / NFI Cluster 2015 2 Contents Abbreviations and acronyms 4 Acknowledgements 5 Executive summary 6 Recommendations 10 1 Introduction 1.1 Evaluation purpose, scope and clients 13 2 Methodology 2.1 Evaluation methodology 14 2.2 Constraints 15 3 Background and context 3.1 Context of the humanitarian response in Somalia 17 3.2 Shelter Cluster deployment 21 4 Findings 4.1 Leadership 23 4.2 Cluster personnel 24 4.3 Supporting shelter service delivery 26 Case study: The electronic cluster (1) 32 4.4 Informing strategic decision-making for the humanitarian response and cluster strategy and planning 34 Case study: Emergency Shelter, Mogadishu (short version) 35 Case study: Transitional shelter, Bosaso (short version) 40 Case study: Permanent Shelter, Galkayo (short version) 42 Case study: The electronic cluster (2) 45 4.5 Monitoring and reporting on implementation of Shelter 49 4.6 Advocacy 50 4.7 Accountability to affected persons 51 4.8 Contingency planning, preparedness and capacity-building 52 5 Conclusions 54 Annex 1 Timeline 56 Annex 2 Natural disasters in Somalia 2006-2014 58 Annex 3 Informants (coordination review) 61 Annex 4 Bibliography 63 Annex