PLAYING the ROLE of AJ in ELLEN MCLAUGHLIN's AJAX in IRAQ By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sophocles, Ajax, Lines 1-171

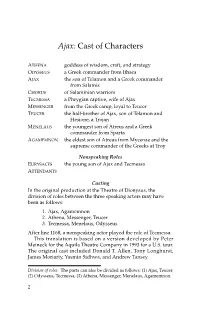

SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 2 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax: Cast of Characters ATHENA goddess of wisdom, craft, and strategy ODYSSEUS a Greek commander from Ithaca AJAX the son of Telamon and a Greek commander from Salamis CHORUS of Salaminian warriors TECMESSA a Phrygian captive, wife of Ajax MESSENGER from the Greek camp, loyal to Teucer TEUCER the half-brother of Ajax, son of Telamon and Hesione, a Trojan MENELAUS the youngest son of Atreus and a Greek commander from Sparta AGAMEMNON the eldest son of Atreus from Mycenae and the supreme commander of the Greeks at Troy Nonspeaking Roles EURYSACES the young son of Ajax and Tecmessa ATTENDANTS Casting In the original production at the Theatre of Dionysus, the division of roles between the three speaking actors may have been as follows: 1. Ajax, Agamemnon 2. Athena, Messenger, Teucer 3. Tecmessa, Menelaus, Odysseus After line 1168, a nonspeaking actor played the role of Tecmessa. This translation is based on a version developed by Peter Meineck for the Aquila Theatre Company in 1993 for a U.S. tour. The original cast included Donald T. Allen, Tony Longhurst, James Moriarty, Yasmin Sidhwa, and Andrew Tansey. Division of roles: The parts can also be divided as follows: (1) Ajax, Teucer; (2) Odysseus, Tecmessa; (3) Athena, Messenger, Menelaus, Agamemnon. 2 SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 3 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax SCENE: Night. The Greek camp at Troy. It is the ninth year of the Trojan War, after the death of Achilles. Odysseus is following tracks that lead him outside the tent of Ajax. -

Gillian Bevan Is an Actor Who Has Played a Wide Variety of Roles in West End and Regional Theatre

Gillian Bevan is an actor who has played a wide variety of roles in West End and regional theatre. Among these roles, she was Dorothy in the Royal Shakespeare Company revival of The Wizard of Oz, Mrs Wilkinson, the dance teacher, in the West End production of Billy Elliot, and Mrs Lovett in the West Yorkshire Playhouse production of Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Gillian has regularly played roles in other Sondheim productions, including Follies, Merrily We Roll Along and Road Show, and she sang at the 80th birthday tribute concert of Company for Stephen Sondheim (Donmar Warehouse). Gillian spent three years with Alan Ayckbourn’s theatre-in-the-round in Scarborough, and her Shakespearian roles include Polonius (Polonia) in the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre production of Hamlet (Autumn, 2014) with Maxine Peake in the title role. Gillian’s many television credits have included Teachers (Channel 4) in which she played Clare Hunter, the Headmistress, and Holby City (BBC1) in which she gave an acclaimed performance as Gina Hope, a sufferer from Motor Neurone Disease, who ends her own life in an assisted suicide clinic. During the early part of 2014, Gillian completed filming London Road, directed by Rufus Norris, the new Artistic Director of the National Theatre. In the summer of 2014 Gillian played the role of Hera, the Queen of the Gods, in The Last Days of Troy by the poet and playwright Simon Armitage. The play, a re-working of The Iliad, had its world premiere at the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre and then transferred to Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, London. -

Press Kit Combined Download

THEATER OF WAR PRODUCTIONS Theater of War Productions provides a framework to engage communities in challenging dialogues about human suffering. Using theater as a catalyst to spark conversations, Theater of War Productions addresses pressing public health and social issues such as combat-related psychological injury, suicide, end-of-life care, police/community relations, prison reform, gun violence, political violence, natural and manmade disaster, domestic violence, substance abuse, and addiction. Since its founding in 2009, Theater of War Productions has facilitated events for over 100,000 people, presenting 22 different tailored programs targeted to diverse communities across the globe. The company works with leading film, theater, and television actors to present dramatic readings of seminal plays—from classical Greek tragedies to modern and contemporary works— followed by town-hall discussions designed to confront social issues by drawing out raw and personal reactions to themes highlighted in the plays and underscoring how they resonate with contemporary audiences. The guided discussions break down stigmas and invite audience members to share their perspectives and experiences, helping to foster empathy, compassion, and an understanding of deeply complex issues. Notable artists who have performed with Theater of War Productions include Blythe Danner, Adam Driver, Reg E. Cathey, Jesse Eisenberg, Paul Giamatti, Jake Gyllenhaal, Alfred Molina, Frances McDormand, Samira Wiley, Jeffrey Wright, and many others. Theater of War Productions was co-founded by Bryan Doerries and Phyllis Kaufman, and Doerries currently serves as the company’s artistic director. In 2017, Doerries, was named NYC Public Artist in Residence (PAIR), a joint appointment with the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs and Department of Veterans’ Services. -

Pause in Homeric Prosody

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/140838 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-26 and may be subject to change. AUDIBLE PUNCTUATION Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Audible Punctuation: Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. Th.L.M. Engelen, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 21 mei 2015 om 14.30 uur precies door Ronald Blankenborg geboren op 23 maart 1971 te Eibergen Promotoren: Prof. dr. A.P.M.H. Lardinois Prof. dr. J.B. Lidov (City University New York, Verenigde Staten) Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. M.G.M. van der Poel Prof. dr. E.J. Bakker (Yale University, Verenigde Staten) Prof. dr. M. Janse (Universiteit Gent, België) Copyright©Ronald Blankenborg 2015 ISBN 978-90-823119-1-4 [email protected] [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Printed by Maarse Printing Cover by Gijs de Reus Audible Punctuation: Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Doctoral Thesis to obtain the degree of doctor from Radboud University Nijmegen on the authority of the Rector Magnificus prof. -

An Investigation Into British Neutrality During the American Civil War 1861-65

AN INVESTIGATION INTO BRITISH NEUTRALITY DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR 1861-65 BY REBECCA CHRISTINE ROBERTS-GAWEN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MA by Research Department of History University of Birmingham November 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis sought to investigate why the British retained their policy of neutrality throughout the American Civil War, 1861-65, and whether the lack of intervention suggested British apathy towards the conflict. It discovered that British intervention was possible in a number of instances, such as the Trent Affair of 1861, but deliberately obstructed Federal diplomacy, such as the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. This thesis suggests that the British public lacked substantial and sustained support for intervention. Some studies have suggested that the Union Blockade of Southern ports may have tempted British intervention. This thesis demonstrates how the British sought and implemented replacement cotton to support the British textile industry. This study also demonstrates that, by the outbreak of the Civil War, British society lacked substantial support for foreign abolitionists’’ campaigns, thus making American slavery a poorly supported reason for intervention. -

![Seven Against Thebes [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8404/seven-against-thebes-pdf-1828404.webp)

Seven Against Thebes [PDF]

AESCHYLUS SEVEN AGAINST THEBES Translated by Ian Johnston Vancouver Island University, Nanaimo, BC, Canada 2012 [Reformatted 2019] This document may be downloaded for personal use. Teachers may distribute it to their students, in whole or in part, in electronic or printed form, without permission and without charge. Performing artists may use the text for public performances and may edit or adapt it to suit their purposes. However, all commercial publication of any part of this translation is prohibited without the permission of the translator. For information please contact Ian Johnston. TRANSLATOR’S NOTE In the following text, the numbers without brackets refer to the English text, and those in square brackets refer to the Greek text. Indented partial lines in the English text are included with the line above in the reckoning. Stage directions and endnotes have been provided by the translator. In this translation, possessives of names ending in -s are usually indicated in the common way (that is, by adding -’s (e.g. Zeus and Zeus’s). This convention adds a syllable to the spoken word (the sound -iz). Sometimes, for metrical reasons, this English text indicates such possession in an alternate manner, with a simple apostrophe. This form of the possessive does not add an extra syllable to the spoken name (e.g., Hermes and Hermes’ are both two-syllable words). BACKGROUND NOTE Aeschylus (c.525 BC to c.456 BC) was one of the three great Greek tragic dramatists whose works have survived. Of his many plays, seven still remain. Aeschylus may have fought against the Persians at Marathon (490 BC), and he did so again at Salamis (480 BC). -

Ancient Greek Culture, with Its Myths, Philosophical Schools, Wars, Means of Warfare, Had Always a Big Appeal Factor on Me

Södertörns högskola | Institutionen för Humaniora Kandidatuppsats 15 hp | Litteraturvetenskap | Höstterminen 2009 This war will never be forgotten – a study of intertextual relations between Homer’s Iliad and Wolfgang Petersen’s Troy Av: Ieva Kisieliute Handledare: Ola Holmgren Table of contents Introduction 3 Theory and method 4 Previous research and selection of material 6 Men behind the Iliad and Troy 7 The Iliad meets Troy 8 Based on, adapted, inspired – levels of intertextuality 8 Different mediums of expression 11 Mutations of the Iliad in Troy 14 The beginning 14 The middle 16 The end 18 Greece vs. Troy = USA vs. Iraq? Possible Allegories 20 Historical ties 21 The nobility of war 22 Defining a hero 25 Metamorphosis of an ancient hero through time 26 The environment of breeding heroes 28 Achilles 29 A torn hero 31 Hector 33 Are Gods dead? 36 Conclusions 39 List of works cited 41 Introduction Ancient Greek culture, with its myths, philosophical schools, wars, means of warfare, had always a big appeal factor on me. I was always fascinated by the grade of impact that ancient Greek culture still has on us – contemporary people. How did it travel through time? How is it that the wars we fight today co closely resemble those of 3000 years ago? While weaving ideas for this paper I thought of means of putting the ancient and the modern together. To find a binding material for two cultural products separated by thousands of years – Homer‟s the Iliad and Wolfgang Petersen‟s film Troy. The main task for me in this paper is to see the “travel of ideas and values” from the Iliad to Troy. -

The Odyssey Homer's

Excerpt terms and conditions This excerpt is available to assist you in the play selection process. You may view, print and download any of our excerpts for perusal purposes. Excerpts are not intended for performance, classroom or other academic use. In any of these cases you will need to purchase playbooks via our website or by phone, fax or mail. A short excerpt is not always indicative of the entire work, and we strongly suggest reading the whole play before planning a production or ordering a cast quantity. HOMER’S THE ODYSSEY Drama by GREGORY A. FALLS and KURT BEATTIE ph: 800-448-7469 www.dramaticpublishing.com The Odyssey (Falls and Beattie) © Dramatic Publishing Company Odyssey (Falls and Beattie - O77) OUTSIDE COVER.indd 1 10/20/2011 4:45:41 PM THE ODYSSEY TYA/USA Outstanding Play Award Winner Produced at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and nationally applauded in professional productions, this is an action-filled adaptation of Homer’s classic, entertaining to children and adults alike. Suitable for a versatile ensemble cast implementing masks, songs, mime and percussive instruments for theatrical effect. Drama. Adapted by Gregory A. Falls and Kurt Beattie. From Homer’s The Odyssey. Cast: 6m., 2w., with doubling, or up to 36 (6m., 2w., 28 either gender). As the goddess Athena introduces the story of Odysseus’ epic journey home from the Trojan War, we see his beautiful wife, Penelope, fending off impatient, would-be suitors. Athena, disguised as an old man, brings news of Odysseus’ journey as the play’s action segues to his adventure. -

Abu Dhabi Review: Ferocious, 21St Century Retelling of Homer's Iliad

Abu Dhabi Review: Ferocious, 21st Century Retelling of Homer’s Iliad starring Denis O’Hare at NYU Abu Dhabi The National, By: Rob Garratt, March 15 2017 War is eternal, the urge to create conflict a deep-seated human impulse – that's the depressing, sledgehammer take-home from An Iliad, a modern one-man retelling of Homer's epic poem currently running at The Arts Centre at NYU Abu Dhabi. Actor Denis O'Hare during a dress rehearsal for An Iliad at The Arts Centre at NYU Abu Dhabi. Courtesy NYU Abu Dhabi War is eternal, the urge to create conflict a deep-seated human impulse – that’s the depressing, sledgehammer take-home from An Iliad, a modern one-man retelling of Homer’s epic poem currently running at The Arts Centre at NYU Abu Dhabi. At the evening’s emotional climax, our narrator spouts a list of dozens of conflicts, from ancient times right up to Aleppo. What slaps the psyche hardest is not just the length of the list, but how many of these wars you might never have heard of – and the fatigue inspired by merely hearing the names of the ones you have. Star and co-writer Denis O’Hare’s (True Blood) solo turn as our haggered, bewildered bard is a ferocious tour de force, the Tony winner stalking the Red Theatre’s stark stage with an crusty charisma and commanding physicality. The Storyteller’s purpose is never made clear – nor is the role of the acknowledged audience, the fourth wall distinctly broken by some early call and response. -

Euripides-Helen.Pdf

Euripides Helen Helen By Euripides, translation by E. P. Coleridge Revised by the Helen Heroization team (Hélène Emeriaud, Claudia Filos, Janet M. Ozsolak, Sarah Scott, Jack Vaughan) Before the palace of Theoklymenos in Egypt. It is near the mouth of the Nile. The tomb of Proteus, the father of Theoklymenos, is visible. Helen is discovered alone before the tomb. Helen These are the lovely pure streams of the Nile, which waters the plain and lands of Egypt, fed by white melting snow instead of rain from heaven. Proteus was king [turannos] of this land when he was alive, [5] living [oikeîn] on the island of Pharos and lord of Egypt; and he married one of the daughters of the sea, Psamathe, after she left Aiakos' bed. She bore two children in his palace here: a son Theoklymenos, [because he spent his life in reverence of the gods,] [10] and a noble daughter, her mother's pride, called Eido in her infancy. But when she came to youth, the season of marriage, she was called Theonoe; for she knew whatever the gods design, both present and to come, [15] having received these honors [tīmai] from her grandfather Nereus. My own fatherland, Sparta, is not without fame, and my father is Tyndareus; but there is indeed a story that Zeus flew to my mother Leda, taking the form of a bird, a swan, [20] which accomplished the deceitful union, fleeing the pursuit of an eagle, if this story is true. My name is Helen; I will tell the evils [kaka] I have suffered [paskhein]. -

Humanities 2 Lecture 5 REVIEW: Aeneid Book IV: One of the Great

Humanities 2 Lecture 5 REVIEW: Aeneid Book IV: one of the great love stories of all time; but it is a love story told as a tale of speech and rhetoric, duty and desire. Dido falls in love with Aeneas, in part through the ministrations of Cupid, but also as he is a story-teller: she becomes fascinated not by Aeneas the actor/hero but by Aeneas the tale-teller/poet. She is “inflamed”: the imagery of fire permeates the book Use of similes to locate the interior lives of characters in the exterior world The coupling of Dido and Aeneas represented as a cosmic, meteorological narrative Rumor as a monstrous personification; Rumor as an “anti-poet” Aeneas as morally compromised; Dido as wronged; Virgil as commentator Dido as fiction-maker; her ruse; her theatrical suicide Aeneid Book V: a period of respite; games as rule-governed behavior that displace military prowess on to controlled ritual competition. The boat race as a kind of answer to the story of the Trojan Horse. Today: Book VI The hell-descent: key feature of epic narrative Theory of poetry: the Sybil as a kind of poet figure; truth mixed with obscurity; scenes of interpretation (augury; haruspication) Emotional content: confrontation with the dead “Allegory”: a story of education; the hero’s education as both experiential and tutorial Poetic content and mythology: the Story of Daedalus and Icarus Philosophical content: development of Platonic and Stoic theories of knowledge Performative impact: we know Virgil read passages from this book to Augustus and Octavia (his sister); the legacy of the emotional response to literature. -

The Barbara and Lawrence Fleischman Theater at the Getty Villa

The Barbara and Lawrence Fleischman Theater at the Getty Villa Thursdays–Saturdays, September 6–29, 2012 View of the Barbara and Lawrence Fleischman Theater and the entrance of the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Villa Tonight’s performance is approximately ninety minutes long, without intermission. As a courtesy to our neighbors, we ask that you keep noise to a minimum while enjoying the production. Please refrain from unnecessarily loud or prolonged applause, shouting, whistling, or any other intrusive conduct during the performance. While exiting the theater and the Getty Villa, please do so quietly. The actors and stage managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. This theater operates under an agreement between the League of Resident Theatres and Actors’ Equity Association. Director Jon Lawrence Rivera is a member of the Society of Stage Directors and Choreographers (SDC), an independent national labor union. Adapted by Nick Salamone Directed by Jon Lawrence Rivera A new production by Playwrights’ Arena THE CAST Helen, queen of Sparta / Rachel Sorsa Menelaos, king of Sparta / Maxwell Caulfield Theoclymenus, ruler of Pharos / Chil Kong Theonoe, devotee of Artemis and sister of Theoclymenus / Natsuko Ohama Hattie, slave to Theoclymenus and Theonoe / Carlease Burke Lady, chorus / Melody Butiu Cleo, chorus / Arséne DeLay Cherry, chorus / Jayme Lake Old Soldier, follower of Menelaos / Robert Almodovar Teucer, younger brother of the Greek hero Ajax / Christopher Rivas Musicians / Brent Crayon, E. A., and David O Understudies / Anita Dashiell-Sparks, Robert Mammana, and Leslie Stevens THE COMPANY Producer / Diane Levine Associate Costume Designer / Byron Nora Composer and Musical Director / David O Costume Assistants / Wendell Carmichael Dramaturge / Mary Louise Hart and Taylor Moten Casting Directors / Russell Boast and Wardrobe Crew / Ellen L.