Development of Party Systems After a Dictatorship: Voting Patterns and Ideological Shaping in Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.THE IMPACT of NATO on the SPANISH AIR FORCE

UNISCI Discussion Papers ISSN: 1696-2206 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Yaniz Velasco, Federico THE IMPACT OF NATO ON THE SPANISH AIR FORCE: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND FUTURE PROSPECTS UNISCI Discussion Papers, núm. 22, enero, 2010, pp. 224-244 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=76712438014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 22 (January / Enero 2010) ISSN 1696-2206 THE IMPACT OF NATO ON THE SPANISH AIR FORCE: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND FUTURE PROSPECTS Federico Yaniz Velasco 1 Brigadier General, Spanish Air Force (Retired) Abstract: The Spanish Air Force is one of the oldest independent Air Forces in the world and the youngest service of the Spanish Armed Forces. Since the early 50’s of the last century it was very much involved in exercises and training with the United States Air Force following the Agreements that Spain signed with the United States in 1953. That is why when Spain joined NATO in 1982 the Spanish Air Force was already somewhat familiar with NATO doctrine and procedures. In the following years, cooperation with NATO was increased dramatically through exercises and, when necessary, in operations. The Spanish Air Force is now ready and well prepared to contribute to the common defence of NATO nations and to participate in NATO led operations whenever the Spanish government decides to do so. -

Vox: a New Far Right in Spain?

VOX: A NEW FAR RIGHT IN SPAIN? By Vicente Rubio-Pueyo Table of Contents Confronting the Far Right.................................................................................................................1 VOX: A New Far Right in Spain? By Vicente Rubio-Pueyo....................................................................................................................2 A Politico-Cultural Genealogy...................................................................................................3 The Neocon Shift and (Spanish) Constitutional Patriotism...................................................4 New Methods, New Media........................................................................................................5 The Catalonian Crisis..................................................................................................................6 Organizational Trajectories within the Spanish Right............................................................7 International Connections.........................................................................................................8 VOX, PP and Ciudadanos: Effects within the Right’s Political Field....................................9 Populist or Neoliberal Far Right? VOX’s Platform...................................................................9 The “Living Spain”: VOX’s Discourse and Its Enemies............................................................11 “Make Spain Great Again”: VOX Historical Vision...................................................................13 -

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy Sophie Diamant Richardson Old Chatham, New York Bachelor of Arts, Oberlin College, 1992 Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics University of Virginia May, 2005 !, 11 !K::;=::: .' P I / j ;/"'" G 2 © Copyright by Sophie Diamant Richardson All Rights Reserved May 2005 3 ABSTRACT Most international relations scholarship concentrates exclusively on cooperation or aggression and dismisses non-conforming behavior as anomalous. Consequently, Chinese foreign policy towards small states is deemed either irrelevant or deviant. Yet an inquiry into the full range of choices available to policymakers shows that a particular set of beliefs – the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence – determined options, thus demonstrating the validity of an alternative rationality that standard approaches cannot apprehend. In theoretical terms, a belief-based explanation suggests that international relations and individual states’ foreign policies are not necessarily determined by a uniformly offensive or defensive posture, and that states can pursue more peaceful security strategies than an “anarchic” system has previously allowed. “Security” is not the one-dimensional, militarized state of being most international relations theory implies. Rather, it is a highly subjective, experience-based construct, such that those with different experiences will pursue different means of trying to create their own security. By examining one detailed longitudinal case, which draws on extensive archival research in China, and three shorter cases, it is shown that Chinese foreign policy makers rarely pursued options outside the Five Principles. -

Casanova, Julían, the Spanish Republic and Civil

This page intentionally left blank The Spanish Republic and Civil War The Spanish Civil War has gone down in history for the horrific violence that it generated. The climate of euphoria and hope that greeted the over- throw of the Spanish monarchy was utterly transformed just five years later by a cruel and destructive civil war. Here, Julián Casanova, one of Spain’s leading historians, offers a magisterial new account of this crit- ical period in Spanish history. He exposes the ways in which the Republic brought into the open simmering tensions between Catholics and hard- line anticlericalists, bosses and workers, Church and State, order and revolution. In 1936, these conflicts tipped over into the sacas, paseos and mass killings that are still passionately debated today. The book also explores the decisive role of the international instability of the 1930s in the duration and outcome of the conflict. Franco’s victory was in the end a victory for Hitler and Mussolini, and for dictatorship over democracy. julián casanova is Professor of Contemporary History at the University of Zaragoza, Spain. He is one of the leading experts on the Second Republic and the Spanish Civil War and has published widely in Spanish and in English. The Spanish Republic and Civil War Julián Casanova Translated by Martin Douch CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521493888 © Julián Casanova 2010 This publication is in copyright. -

Appendix I the Covenant of the League of Nations*

Appendix I The Covenant of the League of Nations* The High Contracting Parties In order to promote international co-operation and to achieve interna tional peace and security by the acceptance of obligations not to resort to war, by the prescription of open, just and honourable relations between na tions, by the firm establishment of the understandings of international law as the actual rule of conduct among Governments, and by the maintenance of justice and a scrupulous respect for all treaty obligations in the dealings of organised peoples with one another, Agree to this Covenant of the League of Nations. Article 1 I. The original Members of the League of Nations shall be those of the Signatories which are named in the Annex to this Covenant and also such of those other States named in the Annex as shall accede without reserva tion to this Covenant. Such accession shall be effected by a Declaration deposited with the Secretariat within two months of the coming into force of the Covenant. Notice thereof shall be sent to all other Members of the League. 2. Any fully self-governing State, Dominion or Colony not named in the Annex may become a Member of the League if its admission is agreed to by two-thirds of the Assembly, provided that it shall give effective guarantees of its sincere intention to observe its international obligations, and shall accept such regulations as may be prescribed by the League in regard to its military, naval and air forces and armaments. 3. Any Member of the League may, after two years' notice of its * The texts printed in italics indicate amendments adopted by the League. -

Military Rearmament and Industrial Competition in Spain Jean-François Berdah

Military Rearmament and Industrial Competition in Spain Jean-François Berdah To cite this version: Jean-François Berdah. Military Rearmament and Industrial Competition in Spain: Germany versus Great Britain, 1921-1931. Tid og Tanke, Oslo: Unipub, 2005, pp.135-168. hal-00180498 HAL Id: hal-00180498 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00180498 Submitted on 19 Oct 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Military Rearmament and Industrial Competition in Spain: Germany vs. Britain (1921-1931) Jean-François Berdah Toulouse II-Le Mirail University, France The loss of Cuba, the Philippines and Porto Rico as a consequence of the Spanish military defeat against the US Navy in 1898 was considered by the public opinion not only as a tragic humiliation, but also as a national disaster. In spite of the subsequent political and moral crisis, the Spanish government and the young King Alfonso XIII intended nevertheless to rebuild the Army according to their strong belief that Spain still remained a great power. But very soon the conscience of the poor technical level of the national industry forced the Spanish government to gain the support of the foreign knowledge and financial resources. -

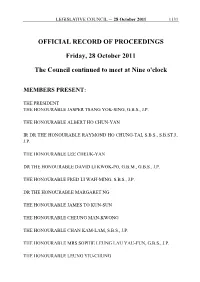

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Friday, 28 October

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 28 October 2011 1131 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Friday, 28 October 2011 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG 1132 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 28 October 2011 DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. -

The Despotic Body

Chapter One The Despotic Body Raza: Espíritu de Franco (1939–1952) ¿Quién se ha metido en las entrañas de España como Franco hasta el punto de no saber ya si Franco es España o si España es Franco? —Ernesto Giménez Caballero, in Carmen Martín Gaite, Usos amorosos “España es un país privilegiado que puede bastarse a sí mismo. Tenemos todo lo que nos hace falta para vivir, y nuestra producción es lo suficientemente abundante para asegurar nuestra propia subsistencia. No tenemos necesidad de importar nada, y es así como nuestro nivel de vida es idéntico al que había antes de la guerra” (Vázquez Montalbán, Los demonios familiares de Franco, 230).1 These words, pronounced by Francisco Franco toward the end of the Spanish Civil War, were assiduously anachronistic and deceptive. In reality the country was completely impoverished after the brutal three-year war. Besides that, the end of the Spanish Civil War on April 1, 1939, was the beginning of more than a decade-long isolation of Spain from the rest of Europe and the world (with the exception of the Axis powers). The isolation lasted until Spain’s acceptance to the UN in 1952. The isolation further impoverished the already stricken 11 12 DESPOTIC BODIES AND TRANSGRESSIVE BODIES country ideologically and culturally, as well as economically. Franco’s statement marked the beginning of the winning side’s attempt to rewrite history. Even though the isolation of Spain was an imposed one, it went hand in hand with autarky, Franco’s ideology of isolationism. In this chapter I will discuss how the dictator is disseminated as the despotic body in political discourse, film, and lit- erature. -

August 2018 Vol. 20, No. 2 September 2018

EDITED BY CARL BAKER BRAD GLOSSERMAN CREATIVE DIRECTOR NICHOLAS CIUFFETELLI MAY – AUGUST 2018 VOL. 20, NO. 2 SEPTEMBER 2018 CC.PACFORUM.ORG PACIFIC FORUM Founded in 1975, the Pacific Forum is a non-profit, foreign policy research institute based in Honolulu, Hawaii. The Forum’s programs encompass current and emerging political, security, economic and business issues and works to help stimulate cooperative policies in the Asia Pacific region through analysis and dialogue undertaken with the region’s leaders in the academic, government, and corporate areas. The Forum collaborates with a network of more than 30 research institutes around the Pacific Rim, drawing on Asian perspectives and disseminating its projects’ findings and recommendations to opinion leaders, governments, and publics throughout the region. We regularly cosponsor conferences with institutes throughout Asia to facilitate nongovernmental institution building as well as to foster cross- fertilization of ideas. A Board of Directors guides the Pacific Forum’s work. The Forum is funded by grants from foundations, corporations, individuals, and governments. The Forum’s studies are objective and nonpartisan and it does not engage in classified or proprietary work. EDITED BY CARL BAKER, PACIFIC FORUM BRAD GLOSSERMAN, TAMA UNIVERSITY CRS/PACIFIC FORUM CREATIVE DIRECTOR NICHOLAS CIUFFETELLI, PACIFIC FORUM MAY – AUGUST 2018 VOL. 20, NO. 2 SEPTEMBER 2018 HONOLULU, HAWAII COMPARATIVE CONNECTIONS A TRIANNUAL E-JOURNAL OF BILATERAL RELATIONS IN THE INDO-ASIA-PACIFIC Bilateral relationships in East Asia have long been important to regional peace and stability, but in the post-Cold War environment, these relationships have taken on a new strategic rationale as countries pursue multiple ties, beyond those with the US, to realize complex political, economic, and security interests. -

5 the Analysis of Far-Right Identities in Italy...2

MEA06 Tutor: Bo Bjurulf Characters: 88,574 Department of Political Science Far-Right Identities in Italy An analysis of contemporary Italian Far-Right Parties Michele Conte Abstract The (re)appearance of different Far-Right parties in Italy during the last decades brought me to the decision to write my Master’s thesis about this topic. Due to the fact that in this country, together with a long tradition of support for Far-Right ideologies, more than one tipology of Far-Right party exists, an interesting scenario is open for the analysis. I will study the cases of Lega Nord and Forza Nuova-Alternativa Sociale. As a first step, I will explain the differences that exist between different ideologies in order to classify these political groups, representing the two cases of analysis in the Italian Far-Right spectrum. I will then build a theory for the formation of Far-Right identities departing from a social constructivist approach. This theory will be tested in the empirical analysis applied to the two study cases. Finally, I will concentrate on the symbolic resources and the discursive strategies that these political actors use in order to construct shared collective identities and to persuade their audience. The results that I will obtain show that while Lega Nord is a Neo-Populist party, Forza Nuova-Alternativa Sociale can be considered as Neo-Fascist. Both the two study cases confirm the theory used to describe the process of Far-Right identity formation in Italy. Regarding the symbolic resources and the discursive strategies of the two political actors, the interesting result is that Lega Nord has shown the tendency to modify its rhetoric, as well as the way it communicates its political messages in order to take advantage of the political situation and increase consensus. -

A Tale of Parallel Lives: the Second Greek Republic and the Second Spanish Republic, 1924–36

Articles 29/2 15/3/99 9:52 am Page 217 T.D. Sfikas A Tale of Parallel Lives: The Second Greek Republic and the Second Spanish Republic, 1924–36 A cursory glance at Greek and Spanish history since the mid- nineteenth century suggests a number of parallels which become more pronounced after the 1920s and culminate in the civil wars of 1936–9 and 1946–9. The idea for a comparative approach to Greek and Spanish history occurred while writing a book on the Greek Civil War, when the social and economic cleavages which had polarized Greek society in the previous decade suggested parallels with the origins of the Spanish crisis of 1936–9. The Second Greek Republic of 1924–35 and the Second Spanish Republic of 1931–6 appeared to have shared more than their partial contemporaneity. The urge for a comparative perspective was reinforced by the need to provide against the threat of a historical and historiographical ethnocentricity; if the objective is to remain aware of the universality of human memory and avoid an ethnocentric perception of historical evolution, then it is not arbitrary to study other nations’ histories and draw comparisons where possible. As for the grouping together of Spain and Greece, objections based on dissimilarities with regard to the level of industrialization and urbanization must not be allowed to weaken the case for a meaningful comparative approach. Political scientists now treat Greece, Spain, Portugal and Italy as the distinct entity of southern Europe, structurally and histori- cally different from the continent’s western and eastern regions. -

Pedlars of Hate: the Violent Impact of the European Far Right

Pedlars of hate: the violent impact of the European far Right Liz Fekete Published by the Institute of Race Relations 2-6 Leeke Street London WC1X 9HS Tel: +44 (0) 20 7837 0041 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7278 0623 Web: www.irr.org.uk Email: [email protected] ©Institute of Race Relations 2012 ISBN 978-0-85001-071-9 Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge the support of the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust and the Open Society Foundations in the researching, production and dissemination of this report. Many of the articles cited in this document have been translated into English by over twenty volunteers who assist the IRR’s European Research Programme. We would especially like to thank Sibille Merz and Dagmar Schatz (who translate from German into English), Joanna Tegnerowicz (who translates from Polish into English) and Kate Harre, Frances Webber and Norberto Laguía Casaus (who translate from Spanish into English). A particular debt is due to Frank Kopperschläger and Andrei Stavila for their generosity in allowing us to use their photographs. In compiling this report the websites of the Internet Centre Against Racism in Europe (www.icare.to) and Romea (www.romea.cz) proved invaluable. Liz Fekete is Executive Director of the Institute of Race Relations and head of its European research programme. Cover photo by Frank Kopperschläger is of the ‘Silence Against Silence’ memorial rally in Berlin on 26 November 2011 to commemorate the victims of the National Socialist Underground. (In Germany, white roses symbolise the resistance movement to the Nazi