Croatian Interpreters and Translators: Profiles and Reported Behaviour in Professional Settings”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCSH Section L

L (The sound) Formal languages La Boderie family (Not Subd Geog) [P235.5] Machine theory UF Boderie family BT Consonants L1 algebras La Bonte Creek (Wyo.) Phonetics UF Algebras, L1 UF LaBonte Creek (Wyo.) L.17 (Transport plane) BT Harmonic analysis BT Rivers—Wyoming USE Scylla (Transport plane) Locally compact groups La Bonte Station (Wyo.) L-29 (Training plane) L2TP (Computer network protocol) UF Camp Marshall (Wyo.) USE Delfin (Training plane) [TK5105.572] Labonte Station (Wyo.) L-98 (Whale) UF Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol (Computer network BT Pony express stations—Wyoming USE Luna (Whale) protocol) Stagecoach stations—Wyoming L. A. Franco (Fictitious character) BT Computer network protocols La Borde Site (France) USE Franco, L. A. (Fictitious character) L98 (Whale) USE Borde Site (France) L.A.K. Reservoir (Wyo.) USE Luna (Whale) La Bourdonnaye family (Not Subd Geog) USE LAK Reservoir (Wyo.) LA 1 (La.) La Braña Region (Spain) L.A. Noire (Game) USE Louisiana Highway 1 (La.) USE Braña Region (Spain) UF Los Angeles Noire (Game) La-5 (Fighter plane) La Branche, Bayou (La.) BT Video games USE Lavochkin La-5 (Fighter plane) UF Bayou La Branche (La.) L.C.C. (Life cycle costing) La-7 (Fighter plane) Bayou Labranche (La.) USE Life cycle costing USE Lavochkin La-7 (Fighter plane) Labranche, Bayou (La.) L.C. Smith shotgun (Not Subd Geog) La Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 BT Bayous—Louisiana UF Smith shotgun USE Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 La Brea Avenue (Los Angeles, Calif.) BT Shotguns La Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) This heading is not valid for use as a geographic L Class (Destroyers : 1939-1948) (Not Subd Geog) USE Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) subdivision. -

YUGOSLAVIA Official No

YUGOSLAVIA Official No. : C. 169. M. 99. 1939. Conf. E. V. R. 23. Geneva, August 1939. LEAGUE OF NATIONS EUROPEAN CONFERENCE O N RURAL LIFE National Monographs drawn up by Governments YUGOSLAVIA Series of League of Nations Publications EUROPEAN CONFERENCE « « O N RURAL LIFE ^ « 5 Peasant from the Cettinje neighbourhood (Montenegro). TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I n t r o d u c t io n ................................................................................................ 5 I. P op u lation : General C onsiderations............................ g II. A griculture : Structure........................................................ 16 III. A grarian R e f o r m .................................................................. 18 1. Ancient Provinces of the Voivodine, Syrmia, Slavonia, Croatia and S lo v en ia .................... 18 2. Southern S e r b i a ......................................................... 19 3. Bosnia and H erzegovina.......................................... 19 4 . D a lm a tia ....................................................................... 19 IV. T echnical I mprovement of the So i l ....................... 21 V. Improvement of Live-stock and Plants .... 24 VI. A gricultural In d u st r ie s .................................................... 27 VII. L and Settlemen r .................................................................. 28 Technical and Cultural Propaganda in Country D i s t r i c t ............................................................................. 30 VIII. A gricultural Co-operation -

Montenegro Media Sector Inquiry with Recommendations for Harmonisation with the Council of Europe and European Union Standards

Montenegro Media Sector Inquiry with Recommendations for Harmonisation with the Council of Europe and European Union standards Report by Tanja Kerševan Smokvina (ed.) Jean-François Furnémont Marc Janssen Dunja Mijatović Jelena Surčulija Milojević Snežana Trpevska 29 December 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................5 PROJECT BACKGROUND 5 FINDINGS AND PROPOSALS 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 13 PURPOSE 13 SCOPE 13 ORGANISATION 14 STRUCTURE 14 METHODOLOGY 16 CH. I: MARKET OVERVIEW AND ASSESSMENT ................................................................................... 17 CONTEXT AND ENVIRONMENT 17 ACCESS AND OFFER 18 ECONOMIC HEALTH AND DYNAMICS 20 LEGAL AND REGULATORY INTERVENTIONS 22 IMPLICATIONS FOR THE PUBLIC 23 POLICY BRIEF 24 CH. II: LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK .............................................................................. 26 HARMONISATION: A STEP FORWARD, TWO BACK 26 LEGISLATION: OVERVIEW AND SUGGESTIONS 26 INSTITUTIONS: GAPS, OVERLAPS AND CAPTURE 35 THE NATIONAL REGULATORY AUTHORITY 40 POLICY BRIEF 42 CH. III: PUBLIC SERVICE MEDIA ......................................................................................................... 44 PUBLICLY FUNDED MEDIA IN MONTENEGRO 44 ORGANISATION AND GOVERNANCE 44 FUNDING 46 AUTONOMY AND INDEPENDENCE 47 CONTENT: UNIVERSALITY AND -

11 BUILDING BRIDGES. an INTRODUCTION Lucia Alberti I

BUILDING BRIDGES. AN INTRODUCTION Lucia Alberti CNR - Istituto di Scienze del Patrimonio Culturale (ISPC) [email protected] I ponti gli piacevano, uniscono separazioni, come una stretta di mano unisce due persone. I ponti cuciono strappi, annullano vuoti, avvicinano lontananze. Mauro Corona, La casa dei sette ponti, Milano, 20121 This volume marks the first in a new monographic series, Bridges, whose aim is to publish the results of the bilateral projects the National Research Council of Italy under- takes with various foreign scientific institutions. The series can be further organized into differing sub-sections, related to the countries involved. The present publication – the first volume in theBridges: Italy Montenegro series – gives an account of the numerous joint-research projects that since 2015 the CNR has conducted with Montenegrin institutions belonging to the Ministry of Sciences and Ministry of Culture of Montenegro. The main topics are related to cultural heritage studies dealing with matters both physical and intangible, with particular reference to the more innovative methodologies and technologies. Already in an advanced stage of preparation is the second volume in this series. Edited by Carla Sfameni and Tatjana Koprivica, it concerns the history of the Italian involvement in the archaeology of Montenegro from the 19th century to the present day. The history of the CNR participation in Montenegro is very recent. In 2013, a first scientific agreement was signed by the former CNR President, Professor Luigi Nicolais, 1 ‘He liked bridges, they unify separate entities, as a handshake joins two persons. Bridges sew up torn holes, fill in empty gaps, and bring far-off things nearer’. -

Projekat Je Finansiran Od Strane Evropske Unije Projekat

Projekat je finansiran Projekat implementira od strane Evropske Unije NVO Phiren Amenca This project is funded by A project implemented by The European Union NGO Phiren Amenca PUBLISHER ROMA YOUTH ORGANISATION “WALK WITH US – PHIREN AMENCA” PODGORICA FOR PUBLISHER ELVIS BERIŠA EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR INTRODUCTION PREPARED BY ELVIS BERIŠA PROOFREADING AND TRANSLATION DŽENITA BRČVAK DESIGN AND TECHNICAL PREPARATION COPY CENTER PRINT COPY CENTER COPIES 50 SUPPORTED BY NGO YOUNG ROMA - HERCEG NOVI MONITORING THE INTEGRATION OF ROMA IN PODGORICA (MIRuPG) MONITORING THE SITUATION OF ROMA IN PODGORICA THROUGH CASE STUDIES Podgorica April, 2017 The report before you is a key product of the project Monitoring the integration of Roma in Podgorica implemented by the Roma Youth Organization “Walk with us - Phiren Amenca” supported by the NGO Young Roma through the awarding of small grants within the project “Joint Initiative for Empowerment of Roma Civil Sector in the Western Balkans and Turkey”, financed by the European Commission. Nouns in the texts, written in the masculine gender refer to the feminine gender, as well. The contents of the Report are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of NGO Young Roma and the European Commision. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................6 DISCRIMINATION IS STRONGER THAN THE DIPLOMA....................................................7 DELAYED CITIZENSHIP.....................................................................................................12 -

Illyrian Policy of Rome in the Late Republic and Early Principate

ILLYRIAN POLICY OF ROME IN THE LATE REPUBLIC AND EARLY PRINCIPATE Danijel Dzino Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics University of Adelaide August 2005 II Table of Contents TITLE PAGE I TABLE OF CONTENTS II ABSTRACT V DECLARATION VI ACKNOWLEDGMENTS VII LIST OF FIGURES VIII LIST OF PLATES AND MAPS IX 1. Introduction, approaches, review of sources and secondary literature 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Rome and Illyricum (a short story) 2 1.3 Methodology 6 1.4.1 Illyrian policy of Rome in the context of world-system analysis: Policy as an interaction between systems 9 1.4.2 The Illyrian policy of Rome in the context of world-system analysis: Working hypothesis 11 1.5 The stages in the Roman Illyrian relationship (the development of a political/constitutional framework) 16 1.6 Themes and approaches: Illyricum in Roman historiography 18 1.7.1 Literature review: primary sources 21 1.7.2 Literature review: modern works 26 2. Illyricum in Roman foreign policy: historical outline, theoretical approaches and geography 2.1 Introduction 30 2.2 Roman foreign policy: Who made it, how and why was it made, and where did it stop 30 2.3 The instruments of Roman foreign policy 36 2.4 The place of Illyricum in the Mediterranean political landscape 39 2.5 The geography and ethnography of pre-Roman Illyricum 43 III 2.5.1 The Greeks and Celts in Illyricum 44 2.5.2 The Illyrian peoples 47 3. The Illyrian policy of Rome 167 – 60 BC: Illyricum - the realm of bifocality 3.1 Introduction 55 3.2 Prelude: the making of bifocality 56 3.3 The South and Central Adriatic 60 3.4 The North Adriatic 65 3.5 Republican policy in Illyricum before Caesar: the assessment 71 4. -

Montenegro: Vassal Or Sovereign?

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Helms School of Government January 2009 Montenegro: Vassal or Sovereign? Octavian Sofansky Stephen R. Bowers Liberty University, [email protected] Marion T. Doss, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Sofansky, Octavian; Bowers, Stephen R.; and Doss, Jr., Marion T., "Montenegro: Vassal or Sovereign?" (2009). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 28. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Helms School of Government at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Montenegro: Vassal or Sovereign? 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................ ................................ ............... 3 INTRODUCTION ................................ ................................ ......................... 4 STRATEGIC SIGNIFICANCE OF MONTENEGRO................................ .............. 6 INTERNAL POLITICAL DUALISM ................................ ................................ 12 RUSSIAN POLICY TOWARDS THE BALKANS................................ ............... 21 MULTILATERAL IMPLICATIONS -

LIST of STUDY PROGRAMMES – University of Montenegro

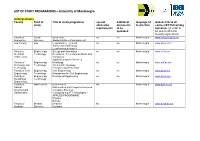

LIST OF STUDY PROGRAMMES – University of Montenegro Undergraduates Faculty Field of Title of study programme special additional language of website link to all study admission documents instruction courses/ECTS/learning requirements to be outcomes (in order to uploaded be able to fill in the learning agreement) Faculty of Social Economics no no Montenegrin www.ekonomija.ac.me Economics Sciences Applied studies of management Law Faculty Law Legal studies – general no no Montenegrin www.pravni.net Safety and Criminology Legal-historical studies Faculty of Engineering, Energy and Automatics no no Montenegrin www.etf.ac.me Electrical Technology Electronics, Telecommunications and Engineering Computers Applied Computer Sciences Faculty of Engineering, Metallurgy no no Montenegrin www.mtf.ac.me Metallurgy and Technology Chemical Technology Technology Environmental Protection Faculty of Civil Engineering, Civil Engineering no no Montenegrin www.gf.ac.me Engineering Technology Management in Civil Engineering Faculty of Engineering, Mechanical Engineering no no Montenegrin www.mf.ac.me Mechanical Technology Engineering Faculty of Mathematics Mathematics No Montenegrin www.pmf.ac.me Natural Mathematics and Computer Sciences Sciences and Computer Sciences Mathematics Computing and IT Technologies - APPLIED PROGRAMME Physics Biology Faculty of Medical Medicine No Montenegrin www.medf.ac.me Medicine Sciences Dentistry LIST OF STUDY PROGRAMMES – University of Montenegro Faculty of Social English Language and Literature No Montenegrin, www.ff.ac.me Philosophy -

Post-Modern Nation Montenegro One Year After Independence

PICTURE STORY Post-modern Nation Montenegro one year after independence September 2007 Post-modern Nation Montenegro one year after independence With its mountainous geography and turbulent history Montenegro is a small Balkan. It is Europe's youngest state, gaining independence in summer 2006. Since then it has not been in the news much. This is in itself remarkable for a country that was once feared to turn into a failed state in a troubled region. Throughout its history Montenegro was known in Europe for its fierce tribes and blood feuds. For centuries Muslim (Ottoman) and Catholic (Venice and Austria) Empires met on its territory. However, in recent years Montenegro surprised those who expected that it would be torn apart by internal conflict. Montenegro was the only one of the six former Yugoslav republics that managed to avoid all violent conflict on its territory since 1989. It is a country without an ethnic majority, two Orthodox churches and no agreed name for the language most of its people speak. The national currency of independent Montenegro is the Euro. Its 620,000 citizens are Orthodox Montenegrins and Orthodox Serbs, Muslim Bosniaks, Catholic and Muslim Albanians, as well as some Croats and other minorities. Upon re-establishing statehood, Montenegro drastically downsized the armed forces it inherited from the joint state with Serbia to 2,500 and destroyed all except one of its 62 tanks. The adjective “wild” is no longer used to scare away potential invaders but to attract tourists. In recent months ESI has taken a closer look at this post-modern nation, from the mountainous North to the Adriatic coastline, to see what independence has brought. -

University of Montenegro Internationalisation Strategy 2020-2025

UNIVERSITY OF MONTENEGRO INTERNATIONALISATION STRATEGY 2020-2025 DRAFT DOCUMENT Project no. 609675-EPP-1-2019-1-ME-EPPKA2-CBHE-SP "The European Commission's support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein." November 2020 1 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 3 2. THE STARTING POINT OF THE INTERNATIONALISATION STRATEGY ............................................... 3 2.1 Vision ...................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Mission .................................................................................................................................... 3 3. OVERVIEW OF CURRENT STATE OF INTERNATIONALISATION ........................................................ 3 3.1 Internationalisation of education .......................................................................................... 3 3.2 Internationalisation of mobility ............................................................................................. 4 3.2.1 International students and incoming student mobility ................................................ 4 3.2.2 Outgoing student mobility ............................................................................................ -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/05/2021 02:14:13AM Via Free Access

journal of language contact 12 (2019) 305-343 brill.com/jlc Language Contact in Social Context: Kinship Terms and Kinship Relations of the Mrkovići in Southern Montenegro Maria S. Morozova Russian Academy of Sciences, Saint Petersburg, Russia [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this article is to study the linguistic evidence of Slavic-Albanian lan- guage contact in the kinship terminology of the Mrkovići, a Muslim Slavic-speaking group in southern Montenegro, and to demonstrate how it refers to the social con- text and the kind of contact situation. The material for this study was collected during fieldwork conducted from 2012 to 2015 in the villages of the Mrkovići area. Kinship terminology of the Mrkovići dialect is compared with that of bcms, Albanian, and the other Balkan languages and dialects. Particular attention is given to the items borrowed from Albanian and Ottoman Turkish, and to the structural borrowing from Albanian. Information presented in the article will be of interest to linguists and anthropologists who investigate kinship terminologies in the world’s languages or do their research in the field of Balkan studies with particular attention to Slavic-Albanian contact and bilingualism. Keywords Mrkovići dialect – kinship terminology – language contact – bilingualism – borrowing – imposition – BCMS – Albanian – Ottoman Turkish © maria s. morozova, 2019 | doi:10.1163/19552629-01202003 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication. Downloaded from Brill.com10/05/2021 02:14:13AM via free access <UN> 306 Morozova 1 Introduction Interaction between Slavs and Albanians in the Balkans has resulted in numer- ous linguistic changes, particularly for those dialects that were in immediate contact with one another. -

The Enigma of Montenegrin History-The Example of Svač

THE ENIGMA OF MONTENEGRIN HISTORY-THE EXAMPLE OF SVAČ JAMES PETTIFER AND AVERIL CAMERON In most periods of Montenegrin history, the coast has been of the greatest significance, from the original ancient traders and colonists who ventured north to found colonial settlements, and throughout the Roman and Byzantine periods. Coastal trade and associated military shipping were what mattered, whether under the Roman and Byzantine empires, the Angevin conquests of the Adriatic in the Middle Ages, or the Venetians. Yet the object of this history has been very little known, or visited. For long periods, Montenegro and Montenegrins did not impinge on the wider European consciousness as either a state or a people. In the nineteenth century, when the first Montenegrin state emerged after the Congress of Berlin in 1878, it was wrapped in a romantic mythology of mountain life that distorted its real history. The emergence of the new country after the May 2006 independence referendum is likely to bring renewed debate about these issues.1 A coastal site such as little known Svač, near the most southern Montenegrin town of Ulcinje, illustrates this process. The isolation of Svač and its near-disappearance is a paradigm of twentieth-century and Cold War border impositions. It illustrates the distortions and displacements of its published history in the Yugoslav period, and its 1 See also Elizabeth Roberts, Realm of the Black Mountain. A History of Montenegro (London, 2007). 2 emergence into normal Montenegrin society in recent years. It illustrates both the complex interfaces on borders, where culture, religion and popular memory interact and often collide, and the difficulties historians face, given the extreme paucity of archaeological work in many places in the non-Greek Balkan lands.2 There has been almost no sustained archaeological work or scientific survey of the site, as is also the case with many others in Montenegro.