Juniperus Communis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Kate, "Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole" (2012). All Theses. 1345. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SASSAFRAS TEA: USING A TRADITIONAL METHOD OF PREPARATION TO REDUCE THE CARCINOGENIC COMPOUND SAFROLE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Forest Resources by Kate Cummings May 2012 Accepted by: Patricia Layton, Ph.D., Committee Chair Karen C. Hall, Ph.D Feng Chen, Ph. D. Christina Wells, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to quantify the carcinogenic compound safrole in the traditional preparation method of making sassafras tea from the root of Sassafras albidum. The traditional method investigated was typical of preparation by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and other Appalachian peoples. Sassafras is a tree common to the eastern coast of the United States, especially in the mountainous regions. Historically and continuing until today, roots of the tree are used to prepare fragrant teas and syrups. -

California Juniper Picture Published with Permission of Bonsai Mirai

Junipers as bonsai V.3.2 April, 2017 Vianney Leduc 1- Introduction a. Esthetic quality The main beauty of junipers lies in the contrast between the living part and the deadwood California juniper Picture published with permission of Bonsai Mirai 2 Sierra juniper Picture published with permission of Bonsai Mirai 3 The influence of the contrast between living portion and deadwood comes from nature 4 We use this contrast seen in nature to style young junipers 5 b. Varieties of junipers Mature and compact foliage (e.g. Sargent juniper) Course foliage (e.g. Common juniper) Mature and juvenile foliage on same tree (e.g. San José juniper) 6 Examples of junipers with delicate and compact foliage o Sargent juniper (Juniperus chinesis sargentii) o Itoigawa juniper (Juniperus chinensis sargentii itoigawa) o Rocky Mountains Juniper (Juniperus scopulorum) o Blaauw juniper (Juniperus chinensis ‘blaauwii’) Examples of juniper with mature but longer foliage o San José juniper (Juniperus chinensis ‘san jose’) o California juniper (Juniperus californica) o Genévrier Sierra (Juniperus occidentalis australis) Examples of junipers with coarse foliage o Common juniper (Juniperus communis) o Needle juniper (Juniperus rigida) 7 c. Basic characteristics of junipers Relatively easy to cultivate Is ideal for most shape and styles of bonsai (except broom style) The wood is soft and easy to bend on younger trees Budding back ability varies greatly between sub-species o Some can bud back on the trunk o Others have a limited capacity Easy to find young specimen in nurseries We normally aim to create the look of an old tree with deadwood: branches should be pointing downward The strength of a juniper lies in its foliage Nice colour contrast between live veins and deadwood Deadwood will decay slowly Can develop a decent bonsai in relatively short time (4 to 5 years) Is an excellent species for all level of enthusiasts 8 2- Basic horticultural requirements a. -

A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus Communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine

© 2021 JETIR March 2021, Volume 8, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine. A Review * Dr. Aafiya Nargis 1, Dr. Ansari Bilquees Mohammad Yunus 2, Dr. Sharique Zohaib 3, Dr. Qutbuddin Shaikh 4, Dr. Naeem Ahmed Shaikh 5 *1 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Niswan wa Qabalat, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon 2 Associate professor, Dept. Tashreeh ul Badan, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon. 3 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Saidla, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Manssoora, Malegaon 4 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Tahaffuzi wa Samaji Tibb, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. 5 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Ain, Uzn, Anf, Halaq wa Asnan, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. Abstract:- Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are 훼-pinene, 훽-pinene, apigenin, sabinene, 훽-sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others Juniperus communis L. (Abhal) is an evergreen aromatic shrub with high therapeutic potential in human diseases. This plant is loaded with nutrition and is rich in aromatic oils and their concentration differ in different parts of the plant (berries, leaves, aerial parts, and root). The fruit berries contain essential oil, invert sugars, resin, catechin , organic acid, terpenic acids, leucoanthocyanidin besides bitter compound (Juniperine), flavonoids, tannins, gums, lignins, wax, etc. -

Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts Plant List

Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts Plant List This PDF document provides additional information to supplement the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management (CZM) Coastal Landscaping website. The plants listed below are good choices for the rugged coastal conditions of Massachusetts. The Coastal Beach Plant List, Coastal Dune Plant List, and Coastal Bank Plant List give recommended species for each specified location (some species overlap because they thrive in various conditions). Photos and descriptions of selected species can be found on the following pages: • Grasses and Perennials • Shrubs and Groundcovers • Trees CZM recommends using native plants wherever possible. The vast majority of the plants listed below are native (which, for purposes of this fact sheet, means they occur naturally in eastern Massachusetts). Certain non-native species with specific coastal landscaping advantages that are not known to be invasive have also been listed. These plants are labeled “not native,” and their state or country of origin is provided. (See definitions for native plant species and non-native plant species at the end of this fact sheet.) Coastal Beach Plant List Plant List for Sheltered Intertidal Areas Sheltered intertidal areas (between the low-tide and high-tide line) of beach, marsh, and even rocky environments are home to particular plant species that can tolerate extreme fluctuations in water, salinity, and temperature. The following plants are appropriate for these conditions along the Massachusetts coast. Black Grass (Juncus gerardii) native Marsh Elder (Iva frutescens) native Saltmarsh Cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) native Saltmeadow Cordgrass (Spartina patens) native Sea Lavender (Limonium carolinianum or nashii) native Spike Grass (Distichlis spicata) native Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) native Plant List for a Dry Beach Dry beach areas are home to plants that can tolerate wind, wind-blown sand, salt spray, and regular interaction with waves and flood waters. -

A Phytopharmacological Review on a Medicinal Plant: Juniperus Communis

Hindawi Publishing Corporation International Scholarly Research Notices Volume 2014, Article ID 634723, 6 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/634723 Review Article A Phytopharmacological Review on a Medicinal Plant: Juniperus communis Souravh Bais,1 Naresh Singh Gill,2 Nitan Rana,2 and Shandeep Shandil2 1 Department of Pharmacology, Rayat Institute of Pharmacy, Vpo Railmajra, Nawanshahr District, Punjab 144533, India 2 Rayat Institute of Pharmacy, Vpo Railmajra, Nawanshahr District, Punjab 144533, India Correspondence should be addressed to Souravh Bais; [email protected] Received 10 June 2014; Revised 28 September 2014; Accepted 15 October 2014; Published 11 November 2014 Academic Editor: Ronaldo F. do Nascimento Copyright © 2014 Souravh Bais et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are -pinene, -pinene, apigenin, sabinene, -sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others. This review includes -

Sacred Heart Game.Pmd

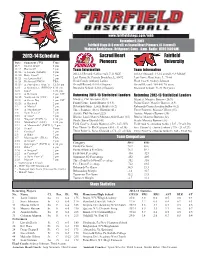

www.fairfieldstags.com/mbb November 9, 2013 Fairfield Stags (0-0 overall) vs Sacred Heart Pioneers. (0-0 overall) Webster Bank Arena - Bridgeport, Conn. - 8 pm - Radio : WICC (600 AM) 2013-14 Schedule Sacred Heart Fairfield Date Opponent (TV) Time Pioneers University 11/9 Sacred Heart! 8 pm 11/13 Hartford# 7 pm Team Information Team Information 11/16 at Loyola (MASN) 8 pm 11/20 Holy Cross# 7 pm 2012-13 Record: 9-20 overall, 7-11 NEC 2012-13 Record: 19-16 overall, 9-9 MAAC 11/23 vs. Louisville#^ 2 pm Last Game: St. Francis Brooklyn, L, 80-92 Last Game: Kent State, L, 73-60 11/24 Richmond/UNC#^ TBA Head Coach: Anthony Latina Head Coach: Sydney Johnson 11/29 at Providence (Fox 1) 12:30 pm Overall Record: 0-0 (1st Season) Overall Record: 105-84 (7th year) 12/6 at Quinnipiac (ESPN3)* 8:30 pm Record at School: 0-0 (1st Season) Record at School: 41-31 (3rd year) 12/8 Iona* 1:30 pm 12/11 at Belmont 7 pm CST Returning 2012-13 Statistical Leaders Returning 2012-13 Statistical Leaders 12/15 Northeastern (SNY) 1 pm 12/21 at Green Bay 1 pm CST Minutes: Phil Gaetano (35.3) Minutes: Maurice Barrow (26.9) 12/28 at Bucknell 2 pm Points/Game: Louis Montes (14.4) Points/Game: Maurice Barrow (8.9) 1/2 at Marist* 7 pm Rebounds/Game: Louis Montes (6.2) Rebounds/Game:Amadou Sidibe (6.2) 1/4 at Manhattan* 7 pm Three Pointers: Steve Glowiak (61) Three Pointers: Marcus Gilbert (35) 1/8 Saint Peter’s* 7 pm Assists: Phil Gaetano (222) Assists: Maruice Barrow (38) 1/10 at Iona* 7 pm Blocks: Louis Montes/Mostafa Abdel Latif (15) Blocks: Maurice Barrow (22) 1/16 Niagara* -

Tips for Cooking with Juniper Hunt Country Marinade

Recipes Tips for Cooking with Juniper • Juniper berries can be used fresh and are commonly sold dried as well. • Add juniper berries to brines and dry rubs for turkey, pork, beef, and wild game. • Berries are typically crushed before added to marinades and sauces. Hunt Country Marinade ¾ cup Cabernet Sauvignon or other dry red wine 3 large garlic cloves, minced ¼ cup balsamic vinegar 3 2x1-inch strips orange peel (orange part only) 3 tablespoons olive oil 3 2x1-inch strips lemon peel (yellow part only) 2 tablespoons unsulfured (light) molasses 8 whole cloves 2 tablespoons chopped fresh thyme or 2 8 whole black peppercorns teaspoons dried 2 bay leaves, broken in half 2 tablespoons chopped fresh rosemary or 2 ¾ teaspoon sa teaspoons dried 1 tablespoon crushed juniper berries or 2 tablespoons gin Mix all ingredients in a medium bowl. (Can be made 2 days ahead. Cover; chill.) Marinate poultry 2 to 4 hours and meat 6 to 12 hours in refrigerator. Drain marinade into saucepan. Boil 1 minute. Pat meat or poultry dry. Grill, basting occasionally with marinade. — Bon Appetit July 1995 via epicurious.com ©2016 by The Herb Society of America www.herbsociety.org 440-256-0514 9019 Kirtland Chardon Road, Kirtland, OH 44094 Recipes Pecan-Crusted Beef Tenderloin with Juniper Jus Two 2 ½ - pound well-trimmed center-cut 1 cup pecans, very finely chopped beef tenderloins, not tied 3 shallots, thinly sliced Salt and freshly ground pepper 1 carrot, thinly sliced 4 tablespoons unsalted butter 1 tablespoon tomato paste 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil 2 teaspoons dried juniper berries, crushed ¼ cup ketchup 1 ½ cups full-bodied red wine, such as Syrah ¼ cup Dijon mustard 1 cup beef demiglace (see Note) 4 large egg yolks Preheat the oven to 425°F. -

Phylogenetic Analyses of Juniperus Species in Turkey and Their Relations with Other Juniperus Based on Cpdna Supervisor: Prof

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY AYSUN DEMET GÜVENDİREN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BIOLOGY APRIL 2015 Approval of the thesis MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA submitted by AYSUN DEMET GÜVENDİREN in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Department of Biological Sciences, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Gülbin Dural Ünver Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Orhan Adalı Head of the Department, Biological Sciences Prof. Dr. Zeki Kaya Supervisor, Dept. of Biological Sciences METU Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Musa Doğan Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Prof. Dr. Zeki Kaya Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Prof.Dr. Hayri Duman Biology Dept., Gazi University Prof. Dr. İrfan Kandemir Biology Dept., Ankara University Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sertaç Önde Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Date: iii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Aysun Demet GÜVENDİREN Signature : iv ABSTRACT MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA Güvendiren, Aysun Demet Ph.D., Department of Biological Sciences Supervisor: Prof. -

Big Game Hunting Practices, Meanings, Motivations And

BIG GAME HUNTING PRACTICES, MEANINGS, MOTIVATIONS, AND CONSTRAINTS: A SURVEY OF OREGON BIG GAME HUNTERS Suresh K. Shrestha, Ph.D. (Brown 2009, Brown et al. 2000) and many wildlife Recreation, Parks and Tourism Resources conservation programs are funded through the sales of West Virginia University hunting licenses (Anderson et al. 1985, Floyd and Lee [email protected] 2002). Robert C. Burns The trend data, however, indicate that the participation West Virginia University of Americans in hunting has been declining over the past decade (USDI and USDC 2006). Similar downward trends have been noted in the number of Abstract.—We conducted a self-administered mail days spent in general hunting and big game hunting, survey in September 2009 with randomly selected and in hunters’ expenditures. Considering the Oregon hunters who had purchased big game hunting dependence of wildlife managers on regulated hunting licenses/tags for the 2008 hunting season. Survey to manage populations of game species as well as pest questions explored hunting practices, the meanings wildlife species, a decline in the number of hunters of and motivations for big game hunting, the will have tremendous direct and indirect managerial, constraints to big game hunting participation, and the social, economic, and environmental implications effects of age, years of hunting experience, hunting (Anderson et al. 1985, Floyd and Lee 2002, Lauber motivations, hunting meanings, and hunting success and Brown 2000, Sun et al. 2005). on overall quality of experience. The study found that although hunters gave high scores to the emotional The situation in the Pacific Northwest, including the and traditional meanings of hunting, their quality of state of Oregon, is even worse with respect to hunting experience depended largely on hunting success. -

The Ecological Status of Juniperus Foetidissima Forest Stands in the Mt

sustainability Article The Ecological Status of Juniperus foetidissima Forest Stands in the Mt. Oiti-Natura 2000 Site in Greece Nikolaos Proutsos * , Alexandra Solomou, George Karetsos, Konstantinia Tsagari, George Mantakas, Konstantinos Kaoukis, Athanassios Bourletsikas and George Lyrintzis Hellenic Agricultural Organization “Demeter”, Institute of Mediterranean Forest Ecosystems, Terma Alkmanos, 11528 Athens, Greece; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (G.K.); [email protected] (K.T.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (K.K.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (G.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-2107-787535 Abstract: Junipers face multiple threats induced both by climate and land use changes, impacting their expansion and reproductive dynamics. The aim of this work is to evaluate the ecological status of Juniperus foetidissima Willd. forest stands in the protected Natura 2000 site of Mt. Oiti in Greece. The study of the ecological status is important for designing and implementing active management and conservation actions for the species’ protection. Tree size characteristics (height, breast height diameter), age, reproductive dynamics, seed production and viability, tree density, sex, and habitat expansion were examined. The data analysis revealed a generally good ecological status of the habitat with high plant diversity. However, at the different juniper stands, subpopulations present high variability and face different problems, such as poor tree density, reduced numbers of juvenile trees or poor seed production, inadequate male:female ratios, a small number of female trees, reduced numbers of seeds with viable embryos, competition with other woody species, grazing, and Citation: Proutsos, N.; Solomou, A.; illegal logging. From the results, the need for site-specific active management and interventions is Karetsos, G.; Tsagari, K.; Mantakas, demonstrated in order to preserve or achieve the good status of the habitat at all stands in the region. -

Spice Basics

SSpicepice BasicsBasics AAllspicellspice Allspice has a pleasantly warm, fragrant aroma. The name refl ects the pungent taste, which resembles a peppery compound of cloves, cinnamon and nutmeg or mace. Good with eggplant, most fruit, pumpkins and other squashes, sweet potatoes and other root vegetables. Combines well with chili, cloves, coriander, garlic, ginger, mace, mustard, pepper, rosemary and thyme. AAnisenise The aroma and taste of the seeds are sweet, licorice like, warm, and fruity, but Indian anise can have the same fragrant, sweet, licorice notes, with mild peppery undertones. The seeds are more subtly fl avored than fennel or star anise. Good with apples, chestnuts, fi gs, fi sh and seafood, nuts, pumpkin and root vegetables. Combines well with allspice, cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, fennel, garlic, nutmeg, pepper and star anise. BBasilasil Sweet basil has a complex sweet, spicy aroma with notes of clove and anise. The fl avor is warming, peppery and clove-like with underlying mint and anise tones. Essential to pesto and pistou. Good with corn, cream cheese, eggplant, eggs, lemon, mozzarella, cheese, olives, pasta, peas, pizza, potatoes, rice, tomatoes, white beans and zucchini. Combines well with capers, chives, cilantro, garlic, marjoram, oregano, mint, parsley, rosemary and thyme. BBayay LLeafeaf Bay has a sweet, balsamic aroma with notes of nutmeg and camphor and a cooling astringency. Fresh leaves are slightly bitter, but the bitterness fades if you keep them for a day or two. Fully dried leaves have a potent fl avor and are best when dried only recently. Good with beef, chestnuts, chicken, citrus fruits, fi sh, game, lamb, lentils, rice, tomatoes, white beans. -

Non-Timber Forest Products and Their Contribution to Households Income

Suleiman et al. Ecological Processes (2017) 6:23 DOI 10.1186/s13717-017-0090-8 RESEARCH Open Access Non-timber forest products and their contribution to households income around Falgore Game Reserve in Kano, Nigeria Muhammad Sabiu Suleiman1*, Vivian Oliver Wasonga1, Judith Syombua Mbau1, Aminu Suleiman2 and Yazan Ahmed Elhadi1 Abstract Introduction: In the recent decades, there has been growing interest in the contribution of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) to livelihoods, development, and poverty alleviation among the rural populace. This has been prompted by the fact that communities living adjacent to forest reserves rely to a great extent on the NTFPs for their livelihoods, and therefore any effort to conserve such resources should as a prerequisite understand how the host communities interact with them. Methods: Multistage sampling technique was used for the study. A representative sample of 400 households was used to explore the utilization of NTFPs and their contribution to households’ income in communities proximate to Falgore Game Reserve (FGR) in Kano State, Nigeria. Descriptive statistics and logistic regression analysis were used to analyze and summarize the data collected. Results: The findings reveal that communities proximate to FGR mostly rely on the reserve for firewood, medicinal herbs, fodder, and fruit nuts for household use and sales. Income from NTFPs accounts for 20–60% of the total income of most (68%) of the sampled households. The utilization of NTFPs was significantly influenced by age, sex, household size, main occupation, distance to forest and market. Conclusions: The findings suggest that NTFPs play an important role in supporting livelihoods, and therefore provide an important safety net for households throughout the year particularly during periods of hardship occasioned by drought.