2010 Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zambia 30 September 2017

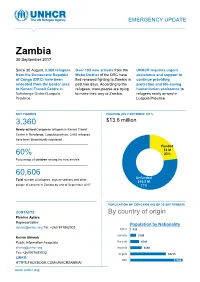

EMERGENCY UPDATE Zambia 30 September 2017 Since 30 August, 3,360 refugees Over 100 new arrivals from the UNHCR requires urgent from the Democratic Republic Moba District of the DRC have assistance and support to of Congo (DRC) have been fled renewed fighting to Zambia in continue providing relocated from the border area past two days. According to the protection and life-saving to Kenani Transit Centre in refugees, more people are trying humanitarian assistance to Nchelenge District/Luapula to make their way to Zambia. refugees newly arrived in Province. Luapula Province. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (AS 2 OCTOBER 2017) 3,360 $13.6 million requested for Zambia operation Newly-arrived Congolese refugees in Kenani Transit Centre in Nchelenge, Luapula province. 2,063 refugees have been biometrically registered Funded $3 M 60% 23% Percentage of children among the new arrivals Unfunded XX% 60,606 [Figure] M Unfunded Total number of refugees, asylum-seekers and other $10.5 M people of concern in Zambia by end of September 2017 77% POPULATION OF CONCERN (AS OF 30 SEPTEMBER) CONTACTS By country of origin Pierrine Aylara Representative Population by Nationality [email protected] Tel: +260 977862002 Other 415 Somalia 3199 Kelvin Shimoh Public Information Associate Burundi 4749 [email protected] Rwanda 6130 Tel: +260979585832 Angola 18715 LINKS: DRC 27398 HTTPS:FACEBOOK.COM/UNHCRZAMBIA/ www.unhcr.org 1 EMERGENCY UPDATE > Zambia / 30 September 2017 Emergency Response Luapula province, northern Zambia Since 30 August, over 3,000 asylum-seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have crossed into northern Zambia. New arrivals are reportedly fleeing insecurity and clashes between Congolese security forces FARDC and a local militia groups in towns of Pweto, Manono, Mitwaba (Haut Katanga Province) as well as in Moba and Kalemie (Tanganyika Province). -

Sister Brigid Gallagher Feast of St

.- The story of the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of )> Jesus and Mary in Zambia Brigid Gallagher { l (Bemba: to comfort, to cradle) The story of the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary in Zambia 1956-2006 Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary Let us praise illustrious people, our ancestors in their successive generations ... whose good works have not been forgotten, and whose names live on for all generations. Book of Ecclesiasticus, 44:1, 1 First published in the United Kingdom in 2014 by Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary Text© 2014 Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary ISBN 978-0-99295480-2 Production, cover design and page layout by Nick Snode ([email protected]) Cover image by Michael Smith (dreamstime.com) Typeset in Palatino 12.5/14.Spt Printed and bound by www.printondemand-worldwide.com, Peterborough, UK Contents Foreword ................................... 5 To th.e reader ................................... 6 Mother Antonia ................................ 7 Chapter 1 Blazing the Trail .................... 9 Chapter 2 Preparing the Way ................. 19 Chapter 3 Making History .................... 24 Chapter4 Into Africa ......................... 32 Chapters 'Ladies in White' - Getting Started ... 42 Chapter6 Historic Events ..................... 47 Chapter 7 'A Greater Sacrifice' ................. 52 Bishop Adolph Furstenberg ..................... 55 Chapter 8 The Winds of Change ............... 62 Map of Zambia ................................ 68 Chapter 9 Eventful Years ..................... 69 Chapter 10 On the Edge of a New Era ........... 79 Chapter 11 'Energy and resourcefulness' ........ 88 Chapter 12 Exploring New Ways ............... 96 Chapter 13 Reading the Signs of the Times ...... 108 Chapter 14 Handing Over .................... 119 Chapter 15 Racing towards the Finish ......... -

Zambia Country Operational Plan (COP) 2016 Strategic Direction Summary

Zambia Country Operational Plan (COP) 2016 Strategic Direction Summary June 14, 2016 Table of Contents Goal Statement 1.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context 1.1 Summary statistics, disease burden and epidemic profile 1.2 Investment profile 1.3 Sustainability profile 1.4 Alignment of PEPFAR investments geographically to burden of disease 1.5 Stakeholder engagement 2.0 Core, near-core and non-core activities for operating cycle 3.0 Geographic and population prioritization 4.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Scale-up Locations and Populations 4.1 Targets for scale-up locations and populations 4.2 Priority population prevention 4.3 Voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) 4.4 Preventing mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) 4.5 HIV testing and counseling (HTS) 4.6 Facility and community-based care and support 4.7 TB/HIV 4.8 Adult treatment 4.9 Pediatric treatment 4.10 Orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) 5.0 Program Activities in Sustained Support Locations and Populations 5.1 Package of services and expected volume in sustained support locations and populations 5.2 Transition plans for redirecting PEPFAR support to scale-up locations and populations 6.0 Program Support Necessary to Achieve Sustained Epidemic Control 6.1 Critical systems investments for achieving key programmatic gaps 6.2 Critical systems investments for achieving priority policies 6.3 Proposed system investments outside of programmatic gaps and priority policies 7.0 USG Management, Operations and Staffing Plan to Achieve Stated Goals Appendix A- Core, Near-core, Non-core Matrix Appendix B- Budget Profile and Resource Projections 2 Goal Statement Along with the Government of the Republic of Zambia (GRZ), the U.S. -

ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018

UNICEF ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018 Zambia Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Zambia/2017/Ayisi ©UNICEF REPORTING PERIOD: JANUARY - JUNE 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 15,425 # of registered refugees in Nchelengue • As of 28 June 2018, a total of 15,425 refugees from the district Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) were registered at (UNHCR, Infographic 28 June 2018) Kenani transit centre in the Luapula Province of Zambia. • UNICEF and partners are supporting the Government of Zambia 79% to provide life-saving services for all the refugees in Kenani of registered refugees are women and transit centre and in the Mantapala permanent settlement area. children • More than half of the refugees have been relocated to Mantapala permanent settlement area. 25,000 • The set-up of basic services in Mantapala is drastically delayed # of expected new refugees from DRC in due to heavy rainfall that has made access roads impassable. Nchelengue District in 2018 • Discussions between UNICEF and the Government are under way to develop a transition and sustainability plan to ensure the US$ 8.8 million continuity of services in refugee hosting areas. UNICEF funding requirement UNICEF’s Response with Partners Funding Status 2018 UNICEF Sector Carry- forward Total Total amount: UNICEF Sector $0.2 m Funds received current Target Results* Target year: $2.5 m Results* Nutrition: # of children admitted for SAM 400 273 400 273 treatment Health: # of children vaccinated against 11,875 6,690 11,875 6,690 measles WASH: # of people provided with access to 15,000 9,253 25,000 15,425 Funding Gap: $6.1 m safe water =68% Child Protection: # of children receiving 5,500 3,657 9,000 4,668 psychosocial and/or other protection services Funds available include funding received for the current year as well as the carry-forward from the previous year. -

Fifty Years of the Kasempa District, Zambia 1964 – 2014 Change and Continuity

FIFTY YEARS OF THE KASEMPA DISTRICT, ZAMBIA 1964 – 2014 CHANGE AND CONTINUITY. A case study of the ups and downs within a remote rural Zambian region during the fifty years since Independence. A descriptive analysis of its demography, geography, infrastructure, agricultural practice and present and traditional cultural aspects, including an account on the traditional ceremony of the installation of regional Headmen and the role and functions of the Kaonde clan structure. Dick Jaeger, 2015 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MAPS AND FIGURES...........................................................................................................3 PART I 4 PREFACE – A WORD OF THANKS.....................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY......................................................................................................6 CHAPTER 1. DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGES.......................................................................................10 ZAMBIA.............................................................................................................................10 KASEMPA DISTRICT........................................................................................................10 CHAPTER 2. AGRICULTURE............................................................................................................12 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................12 -

Improved Complementary Foods Recipe Booklet

National Food and Government of the Nutrition Commission Republic of Zambia Improved Complementary Foods Recipe Booklet Family Foods for Breastfed Children in Zambia Technical collaboration and financial support by Financial support for printing was provided by UNICEF, Zambia Improved Complementary Foods Recipe Booklet Family Foods for Breastfed Children in Zambia Lusaka, Zambia 2007 Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion what- soever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. National Food and Nutrition Commission, Government of the Republic of Zambia and The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2007 All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copy- right holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Chief, Publishing Management Service, Information Di- vision, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected] and to The Director, National Food and Nutrition Commission, Plot No. 5112, Lumumba Road, P.O. Box 32669, Lusaka, Zambia ISBN 9982-54-005-X Acknowledgements The recipes in this booklet were developed and field-tested in Luapula Province. -

National Health Insurance Management Authority

NATIONAL HEALTH INSURANCE MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY LIST OF ACCREDITED HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS AS OF SEPTEMBER 2021 Type of Facility Physical Address (Govt, Private, S/N Provider Name Service Type Province District Faith Based) 1 Liteta District Hospital Hospital Central Chisamba Government 2 Chitambo District Hospital Hospital Central Chitambo Government 3 Itezhi-tezhi District Hospital Hospital Central Itezhi tezhi Government 4 Kabwe Central Hospital Hospital Central Kabwe Government 5 Kabwe Women, Newborn & Children's HospHospital Central Kabwe Government 6 Kapiri Mposhi District Hospital Hospital Central Kapiri Mposhi Government 7 Mkushi District Hospital Hospital Central Mkushi Government 8 Mumbwa District Hospital Hospital Central Mumbwa Government 9 Nangoma Mission Hospital Hospital Central Mumbwa Faith Based 10 Serenje District Hospital Hospital Central Serenje Government 11 Kakoso 1st Level Hospital Hospital Copperbelt Chililabombwe Government 12 Nchanga North General Hospital Hospital Copperbelt Chingola Government 13 Kalulushi General Hospital Hospital Copperbelt Kalulushi Government 14 Kitwe Teaching Hospital Hospital Copperbelt Kitwe. Government 15 Roan Antelope General Hospital Hospital Copperbelt Luanshya Government 16 Thomson District Hospital Hospital Copperbelt Luanshya Government 17 Lufwanyama District Hospital Hospital Copperbelt Lufwanyama Government 18 Masaiti District Hospital Hospital Copperbelt Masaiti Government 19 Mpongwe Mission Hospital Hospital Copperbelt Mpongwe Faith Based 20 St. Theresa Mission Hospital Hospital -

Profiles of Active Civil Society Organisations in North-Western, Copperbelt and Southern Provinces of Zambia

Profiles of Active Civil Society Organisations in North-Western, Copperbelt and Southern Provinces of Zambia On behalf of Implemented by Published by: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Registered offices Bonn and Eschborn, Germany Address Civil Society Participation Programme (CSPP) Mpile Office Park, 3rd floor 74 Independence Avenue Lusaka, Zambia P +260 211 250 894 E [email protected] I www.giz.de/en Programme: Civil society participation in governance reform and poverty reduction Author: Isaac Ngoma, GFA Consulting Group GmbH Editor: Markus Zwenke, GFA Consulting Group GmbH, Eulenkrugstraße 82, 22359 Hamburg, Germany Design/layout: GFA Consulting Group GmbH and IE Zhdanovich Photo credits/sources: GFA Consulting Group GmbH On behalf of German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) As of June, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENT ACTIVE CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS IN NORTH-WESTERN PROVINCE � � � � � �7 Dream Achievers Academy �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Anti-voter Apathy Project ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Mentra Youth Zambia . 10 The Africa Youth Initiative Network �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 11 Radio Kabangabanga ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

The Case of Honey in Zambia the Case

Small-scale with outstanding economic potential enterprises woodland-based In some countries, honey and beeswax are so important the term ‘beekeeping’ appears in the titles of some government ministries. The significance of honey and beeswax in local livelihoods is nowhere more apparent than in the Miombo woodlands of southern Africa. Bee-keeping is a vital source of income for many poor and remote rural producers throughout the Miombo, often because it is highly suited to small scale farming. This detailed Non-Timber Forest Product study from Zambia examines beekeeping’s livelihood role from a range of perspectives, including market factors, production methods and measures for harnessing beekeeping to help reduce poverty. The caseThe in Zambia of honey ISBN 979-24-4673-7 Small-scale woodland-based enterprises with outstanding economic potential 9 789792 446739 The case of honey in Zambia G. Mickels-Kokwe G. Mickels-Kokwe Small-scale woodland-based enterprises with outstanding economic potential The case of honey in Zambia G. Mickels-Kokwe National Library of Indonesia Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mickels-Kokwe, G. Small-scale woodland-based enterprises with outstanding economic potential: the case of honey in Zambia/by G. Mickels-Kokwe. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 2006. ISBN 979-24-4673-7 82p. CABI thesaurus: 1. small businesses 2. honey 3. beekeeping 4. commercial beekeeping 5. non- timber forest products 6. production 7. processing 8. trade 9.government policy 10. woodlands 11. case studies 12. Zambia I. Title © 2006 by CIFOR All rights reserved. Published in 2006 Printed by Subur Printing, Jakarta Design and Layout by Catur Wahyu and Eko Prianto Cover photo by Mercy Mwape of the Forestry Department of Zambia Published by Center for International Forestry Research Jl. -

Household Food Security and Nutrition in the Luapula Valley, Zambia

22 Household food security and nutrition in the Luapula Valley, Zambia K. Callens and E.C. Phiri Karel Callens is Chief Technical Adviser and Elizabeth C. Phiri is National Project Coordinator for the Improving Household Food Security and Nutrition Project. he Luapula Valley of northern Zambia has significant Improvements in the production of other important food crops T natural resources, and the main road cutting through the were neglected. valley has attracted many people to the area. Of the In the Luapula Valley, rates of chronic malnutrition and population of 207 000, the majority of people live along the micronutrient deficiencies are unacceptably high. Preliminary lake, the lagoon and the river (Figure 1). Fishing is the results from two nutrition surveys carried out in the area in principal economic activity, and agriculture is practised September 1997 and May 1998 indicated that about 65 percent further inland. The diet of most households is based on two of children under five years of age were stunted because of main staples: cassava and maize. As relish people consume fish chronic protein-energy malnutrition, while 3.7 percent were in those areas with access to water resources and a limited wasted during the rainy season and 2.5 percent during the dry number of less abundant and seasonally available food crops season as a result of acute malnutrition. According to a such as sweet potatoes, groundnuts, bambara nuts, cowpeas participatory rural appraisal carried out by the Zambian and beans as well as indigenous and other vegetables. Palm oil Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries, the Ministry of is also consumed in a few villages where oil-palm trees are Health, the Ministry of Community Development and Social found. -

Zambia USADF Country Portfolio

Zambia USADF Country Portfolio Overview: Country program established in 1984 and reopened in U.S. African Development Foundation Partner Organization: Keepers Zambia 2004. USADF currently manages a portfolio of 23 projects and one Country Program Coordinator: Guy Kahokola Foundation (KZF) Cooperative Agreement. Total active commitment is $2.9 million. Suite 103 Foxdale Court Office Park Program Manager: Victor Makasa Agricultural investments total $2.6 million. Youth-led enterprise 609 Zambezi Road, Roma Tel: +260 211 293333 investments total $20,000. Lusaka, Zambia Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Country Strategy: The program focuses on support to agricultural enterprises, including organic farming as Zambia has been identified as a Feed the Future country. In addition, there are investments in off-grid energy and youth led-enterprises. Enterprise Duration Grant Size Description Mongu Dairy Cooperative Society 2012-2017 $152,381 Sector: Agriculture (Dairy) Limited Town/City: Mongu District in the Western Province 2705-ZMB Summary: The project funds will be used to increase the production and sales of milk through the purchase of improved breed cows, transportation, and storage equipment. Chibusa Home Based Care 2013-2018 $187,789 Sector: Agriculture (Food Processing) Association Town/City: Mungwi District in the Northern Province of Zambia 2925-ZMB Summary: The project funds will be used to provide working capital for purchasing grains, increase milling capacity, build a storage warehouse, and provide funds to improve marketing. Ushaa Area Farmers Association 2013-2018 $94,960 Sector: Agriculture (Rice) Limited Town/City: Mongu District in the Western Province of Zambia 2937-ZMB Summary: The project funds will be used to provide working capital for purchasing rice, build a storage warehouse, and provide funds to improve marketing. -

FORM #3 Grants Solicitation and Management Quarterly

FORM #3 Grants Solicitation and Management Quarterly Progress Report Grantee Name: Maternal and Child Survival Program Grant Number: # AID-OAA-A-14-00028 Primary contact person regarding this report: Mira Thompson ([email protected]) Reporting for the quarter Period: Year 3, Quarter 1 (October –December 2018) 1. Briefly describe any significant highlights/accomplishments that took place during this reporting period. Please limit your comments to a maximum of 4 to 6 sentences. During this reporting period, MCSP Zambia: Supported MOH to conduct a data quality assessment to identify and address data quality gaps that some districts have been recording due to inability to correctly interpret data elements in HMIS tools. Some districts lacked the revised registers as well. Collected data on Phase 2 of the TA study looking at the acceptability, level of influence, and results of MCSP’s TA model that supports the G2G granting mechanism. Data collection included interviews with 53 MOH staff from 4 provinces, 20 districts and 20 health facilities. Supported 16 districts in mentorship and service quality assessment (SQA) to support planning and decision-making. In the period under review, MCSP established that multidisciplinary mentorship teams in 10 districts in Luapula Province were functional. Continued with the eIMCI/EPI course orientation in all Provinces. By the end of the quarter under review, in Muchinga 26 HCWs had completed the course, increasing the number of HCWs who improved EPI knowledge and can manage children using IMNCI Guidelines. In Southern Province, 19 mentors from 4 districts were oriented through the electronic EPI/IMNCI interactive learning and had the software installed on their computers.