Britain on the Front Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

Globe 140611

June 2011 INSIDE Who’s keeping an eye on College Green? The Memory Shed all our histories Music in Exile A taste of England Welcome to my home My favourite food… Kenya comes to Bristol Faith in the City Bristol City of Sanctuary Steering Committee Bristol City of Sanctuary Supporters CONTENTS June Burrough (Chair) Founder and Director, The Pierian Centre Co If your organisation would like to be Hotwells Primary School ng 3 Letter to Bristol ratula added this lists, please visit Imayla International Organisation tions Lorraine Ayensu Team Manager, Asylum Support and Refugee In - www.cityofsanctuary.org/bristol for Migration Inderjit Bhogal tegration Team, Bristol City Council Churches Council for Industry and Alistair Beattie Chief Executive, Faithnetsouthwest ACTA Community Theatre Social Responsibility 4 Editorial Caroline Beatty Co-ordinator, The Welcome Centre, Bristol African and Caribbean Chamber of John Wesley’s Chapel Mike Jempson to Bris Commerce and Enterprise Kalahari Moon to Refugee Rights l – Jo Benefield Bristol Defend Asylum Campaign African Initiatives Kenya Association in Bristol 5 A movement gaining ground Adam Cutler Bristol Central Libraries African Voices Forum Kingswood Methodist Church Stan Hazell Afrika Eye Malcom X Centre Mohammed Elsharif Secretary, Sudanese Association Amnesty International Bristol MDC Bristol Elinor Harris Area Manager, Refugee Action, Bristol p 6-7 The Memory Shed ro Group Methodist Church, South West ud to b Reverend Canon Tim Higgins The City Canon, Bristol Cathedral Eugene Byrne e Anglo-Iranian -

The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 Building Unity Through State Narratives: The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941 Colin Cook University of Central Florida Part of the European History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Cook, Colin, "Building Unity Through State Narratives: The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6734. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6734 BUILDING UNITY THROUGH STATE NARRATIVES: THE EVOLVING BRITISH MEDIA DISCOURSE DURING WORLD WAR II, 1939-1941 by COLIN COOK J.D. University of Florida, 2012 B.A. University of North Florida, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2019 ABSTRACT The British media discourse evolved during the first two years of World War II, as state narratives and censorship began taking a more prominent role. I trace this shift through an examination of newspapers from three British regions during this period, including London, the Southwest, and the North. My research demonstrates that at the start of the war, the press featured early unity in support of the British war effort, with some regional variation. -

Prostitution in Bristol and Nantes, 1750-1815: a Comparative Study

Prostitution in Bristol and Nantes, 1750-1815: A comparative study Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy at the University of Leicester Marion Pluskota Centre for Urban History University of Leicester July 2011 Abstract This thesis is centred on prostitution in Nantes and Bristol, two port cities in France and England, between 1750 and 1815. The objectives of this research are fourfold: first, to understand the socio-economic characteristics of prostitution in these two port cities. Secondly, it aims to identify the similarities and the differences between Nantes and Bristol in the treatment of prostitution and in the evolution of mentalités by highlighting the local responses to prostitution. The third objective is to analyse the network of prostitution, in other words the relations prostitutes had with their family, the tenants of public houses, the lodging-keepers and the agents of the law to demonstrate if the women were living in a state of dependency. Finally, the geography of prostitution and its evolution between 1750 and 1815 is studied and put into perspective with the socio- economic context of the different districts to explain the spatial distribution of prostitutes in these two port cities. The methodology used relies on a comparative approach based on a vast corpus of archives, which notably includes judicial archives and newspapers. Qualitative and quantitative research allows the construction of relational databases, which highlight similar patterns of prostitution in both cities. When data is missing and a strict comparison between Nantes and Bristol is made impossible, extrapolations and comparisons with studies on different cities are used to draw subsequent conclusions. -

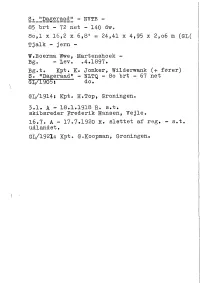

85 Brt - 72 Net - 140 Dw

S^o^^Dageraad*^ - WVTB - 85 brt - 72 net - 140 dw. 8o,l x 16,2 x 6,8' = 24,41 x 4,95 x 2,o6 m (GL( Tjalk - jern - W.Boerma Wwe, Martenshoek - Bg. - lev. .4.1897. Bg.t. Kpt. Ko Jonker, Wilderwank (+ fører) S. "Dageraad" - NLTQ - 8o brt - 67 net GI/1905: do. GL/1914: KptO H.Top, Groningen. 3.1. A - 18.1.1918 R. s.t. skibsreder Frederik Hansen, Vejle, 16.7. A - 17.7.1920 R. slettet af reg. - s.t. udlandet. Gl/1921: Kpt. G.Koopman, Groningen. ^Dagmar^ - HBKN - , 187,81 hrt - 181/173 NRT - E.C. Christiansen, Flenshurg - 1856, omhg. Marstal 1871. ex "Alma" af Marstal - Flb.l876$ C.C.Black, Marstal. 17.2.1896: s.t. Island - SDagmarS - NLJV - 292,99 brt - 282 net - lo2,9 x 26,1 x 14,1 (KM) Bark/Brig - eg og fyr - 1 dæk - hækbg. med fladt spejl - middelf. bov med glat stævn. Bg. Fiume - 1848 - BV/1874: G. Mariani & Co., Fiume: "Fidente" - 297 R.T. 29.8.1873 anrn. s.t. partrederi, Nyborg - "DagmarS - Frcs. 4o.5oo mægler Hans Friis (Møller) - BR 4/24, konsul H.W. Clausen - BR fra 1875 6/24 købm. CF. Sørensen 4/24 " Martin Jensen 4/24 skf. C.J. Bøye 3/24 skf. B.A. Børresen - alle Nyborg - 3/24 29.12.1879: Forlist p.r. North Shields - Tuborg havn med kul - Sunket i Kattegat ca. 6 mil SV for Kråkan, da skibet ramtes af brådsø, der knækkede alle støtter, ramponerede skibets ene side, knuste båden og ødelagde pumperne. -

Curriculum Knowledge Organiser

Curriculum Knowledge Organiser Year Six History: WW2 — Knowledge How did life change for children during WW2? Year six History: WW2 — Skills WALT: To understand how life WALT: To identify key countries in- WALT: TO understand how WALT: To understand how WALT: TO understand the changed during WW2. (Wow event– WALT: To order key events ALT: To understand significant volved in WW2 and life on the affects of Dig for victory allotment and creating the human geography of of WW2 events of WW2. ration carrot cake) to find these on a map. London/ Bristol changed after WW2. home front Changed during WW2. WW2 on children. Timeline of key events Key Figures Skills Teaching Strategies 1939 1st Sept Germany invades Poland. Hitler 1889 –1945 German dictator during WWII and leader of the Nazi political party. Winston Churchill British Prime minister from 1940 to 1945 then Chronological understanding Make a timeline to be displayed in class with key dates again from 1951 to 1955. He is famous for his 1939 3rd Sept Britain declares war on Ger- 1874 –1965 from WW2, add dates and events throughout each lesson speeches that inspired people to continue Place the time studied on a time line and sequence many. based on knowledge learned. Children create own time fighting. events. lines of significant events during ww2. 1940 Winston Churchill replaces Chamber- Neville Chamberlin 1869– British Prime minster from May 1937– May 1940 1940. He is famous for declaring that Britain was Map Skills Locate countries on a globe/map. lain as PM. Know which countries were involved in World War Two and at war with Germany. -

Material Cultures of Childhood in Second World War Britain

Material Cultures of Childhood in Second World War Britain How do children cope when their world is transformed by war? This book draws on memory narratives to construct an historical anthropology of childhood in Second World Britain, focusing on objects and spaces such as gas masks, air raid shelters and bombed-out buildings. In their struggles to cope with the fears and upheavals of wartime, with families divided and familiar landscapes lost or transformed, children reimagined and reshaped these material traces of conflict into toys, treasures and playgrounds. This study of the material worlds of wartime childhood offers a unique viewpoint into an extraordinary period in history with powerful resonances across global conflicts into the present day. Gabriel Moshenska is Associate Professor in Public Archaeology at University College London, UK. Material Culture and Modern Conflict Series editors: Nicholas J. Saunders, University of Bristol, Paul Cornish, Imperial War Museum, London Modern warfare is a unique cultural phenomenon. While many conflicts in history have produced dramatic shifts in human behaviour, the industrialized nature of modern war possesses a material and psychological intensity that embodies the extremes of our behaviours, from the total economic mobiliza- tion of a nation state to the unbearable pain of individual loss. Fundamen- tally, war is the transformation of matter through the agency of destruction, and the character of modern technological warfare is such that it simulta- neously creates and destroys more than any previous kind of conflict. The material culture of modern wars can be small (a bullet, machine-gun or gas mask), intermediate (a tank, aeroplane, or war memorial), and large (a battleship, a museum, or an entire contested landscape). -

Why Did Britain Go to War in 1937? (The Front Line)

Unit No. 19A Year Group: UKS2 Question: Why did Britain go to war in 1937? (The Front Line) Timeline of World War 2 I already know… Essential Knowledge and Vocabulary The Phoney War Sept 1939 – April 1940 European countries and cities – features of navigation Germany invades Poland. Britain and Sep The war was caused by long and short term France declare war on Germany – Start of Physical and human features of Krakow, Poland. Causes 1939 factors World War 2 World War 2 was from 1939 until 1945 Allies – see Countries which fought on the British side – in Blitzkrieg April 1940 – June 1940 Adolf Hitler was the leader of the Nazi Party in map alliance/friendship with us Dunkirk evacuated (UK troops rescued from beaches) Germany. The war started when Adolf Hitler and his and France surrenders to Germany. Germany uses Countries with found against the British side troops invaded Poland, on 1st September 1939. Axis – see map ‘blitzkrieg’ to take over much of Western Europe Britain and Empire Alone July 1940 – June 1941 Neville Chamberlin was the Prime Minster on Britain. Neutral Countries with fought supporting neither side Germany launches air attacks on Britain He declared war on Germany on 3rd September 1939. A long narrow ditch used for troops to shelter July Germany, Italy and Japan signed the Trenches 1940 Battles were fought in Asia, Africa and Europe, on the from enemy fire Tripartite Pack creating an alliance ground and in the air. The Battle of Britain was an air Mass murder (genocide) of Jews and other The Tide Turns 1941 - 1943 Holocaust battle between the Luftwaffe (German Air force) and the groups by the Nazis June Hitler invades Russia in Operation RAF (Royal British Airforce). -

History Curriculum Framework

History Curriculum Framework Intent: The Futura Learning Partnership (FLP) intent for history is that a high-quality history education will inspire children to have a curiosity and fascination about the local area and Britain’s past and that of the wider world as well. Children will be able to think critically, weigh evidence, sift arguments, and develop perspective and judgement. The children’s deep learning of history and its related information gathering skills will enable them to have an understanding of where we have come from and how this has been influenced by the wider world and different cultural heritages. This in turn will enable us to learn from the past, model the future and understand society and the child’s place within it. Furthermore, it gives us a view of other cultures and their development through time. We believe that learning about historical events provides an important context for the development of pupils’ key learning skills, particularly communication, working with others, problem solving and critical thinking skills and that this will be done not just through experiences in the classroom but also through the use of field work and educational visits. Inclusion: Our curriculum is ambitious for all and strives to address inclusion and disadvantage in its intent and implementation 1 Aims: Underpinning the intent are key substantive concepts: Chronological A secure knowledge of the order of events necessarily underpins any attempt to explain cause and consequence or to chart the process of Understanding change and continuity. Historical Concepts 1. Some concepts and terms (such as Calvinism or Menshivism) are highly specific to a particular period or place – and it is easy to recognise that their meaning needs to be explicitly taught. -

Creative Approaches to Learning About Bristol Blitz. Professional Journal

Harnett, P. (2013) creative approaches to learning about Bristol Blitz. Professional Journal . We recommend you cite the published version. The publisher’s URL is https://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/secure/21734/ Refereed: No (no note) Disclaimer UWE has obtained warranties from all depositors as to their title in the material deposited and as to their right to deposit such material. UWE makes no representation or warranties of commercial utility, title, or fit- ness for a particular purpose or any other warranty, express or implied in respect of any material deposited. UWE makes no representation that the use of the materials will not infringe any patent, copyright, trademark or other property or proprietary rights. UWE accepts no liability for any infringement of intellectual property rights in any material deposited but will remove such material from public view pend- ing investigation in the event of an allegation of any such infringement. PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR TEXT. CASE STUDY Case Study 4: Creative approaches to learning about the Bristol blitz — Penelope Harnett, Greg Davies, Steve Baxter and Robbie Keast Introduction the children did have opportunities of imaginative experience that is so The University of the West of England, to consider the points of view and conducive to learning. It demonstrates Bristol has strong partnerships with feelings of people living at the time. how active participation in workshops many local schools and is developing For example, cooking with war captures the attention of everyone, and innovative ways in working with time ingredients enabled children positively encourages children to learn. trainees, teachers and children. The to appreciate the lack of variety in Knowledge can be obtained from books approach taken to learning about the war time diets. -

Our Inherited City Bristol Heritage Framework 2015 - 2018

Our Inherited City Bristol Heritage Framework 2015 - 2018 CITY DESIGN PLACE DIRECTORATE October 2015 Contents Preface 3 Introduction 4 The story of place 9 The story of the ‘place by the bridge’ 10 The benefits of heritage 14 Historic streets 16 Historic neighbourhoods 18 Heritage and sustainable placemaking 20 Heritage and climate change 24 Heritage in practice 26 Our Approach 34 Our Priorities 46 Sharing objectives 62 Further information 68 Glossary 74 Prepared by City Design Group, Planning Division, Place Directorate, Bristol City Council © City Design Group, 2015 Aerial photography © Blom Pictometry, 2012 ©Crown Copyright and database right 2014, Ordnance Survey 100023406 2 Preface Heritage and the vision for Bristol Bristol has a unique historic environment. Each Heritage is a key component in creating quality places. of the city’s neighbourhoods has an individual Heritage will continue to contribute to the delivery of physical identity and distinctiveness that has the Vision for Bristol set out by the Mayor, November developed incrementally over many generations. 2013. Heritage fits specifically with the Vision for place Our historic environment represents a major part and the aspiration for Building successful places, which of the city’s DNA. We have inherited an outstanding makes direct reference to the rejuvenation of the legacy of iconic and everyday buildings, structures historic centre and regeneration in the Temple Quarter and landscapes that positively contribute to the Enterprise Zone. economic, environmental and social wellbeing of This Vision is an extension of the objectives set out in Bristol. This legacy needs to be stewarded with the Bristol Core Strategy that underpins place making sensitivity, creativity and innovation to ensure that in Bristol. -

Weir, Paul.Pdf

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details BRITISH ATTITUDES TO THE AERIAL BOMBARDMENT OF GERMAN CITIES DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR PAUL WEIR PHD UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX SEPTEMBER 2014 2 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. However, the thesis incorporates to the extent indicated below, material already submitted as part of required coursework and/or for the degree of Master of Arts in Modern European History which was awarded by the University of Sussex. Signature: Chapter Four, entitled: “‘A city of the dead’: Dresden and the end of the war”, is a reworked version of my Master of Arts dissertation, completed in 2008. The version included here incorporates original research carried out during my current period of registration at the University of Sussex. The argument has been substantially developed to situate this part of my research within the broader scope of my thesis.