Vytautas Bacevičius in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOC 0328 CD Booklet.Indd

VYTAUTAS BACEVIČIUS, LITHUANIAN RADICAL by Šarūnas Nakas During his lifetime the name of Vytautas Bacevičius (1905–70) was almost unknown and few of his major works were published or performed, but he is now considered to have been the foremost fgure in Lithuanian music of the mid-twentieth century. He built his reputation as a modern composer in the decades preceding the Second World War, also pursuing an international career as a virtuoso pianist by appearing as recitalist and soloist with the leading orchestras in major venues in Europe, South America and later in the United States. His emergence into the musical life of the time was as a visionary, trendsetter and promoter of modern urban ideology, ardently defending his views against public criticism. Bacevičius was born in Łódź, in central Poland, into a family of joint Polish- Lithuanian origin. Vytautas was the only sibling to identify himself as Lithuanian, even though the father taught his two sons and two daughters Lithuanian and ofen took them to spend the summers in his homeland.1 Te best-known member of the family was Vytautas’ younger sister Grażyna Bacewicz (1909–69), who remained in Poland to achieve prominence as one of the most gifed Polish violinists and female composers. Afer graduating from the private conservatoire in Łódź, in 1926, Bacevičius moved to Kaunas, the inter-War capital of Lithuania, where he studied philosophy and aesthetics at the Vytautas Magnus University. In 1927 a state scholarship enabled him to pursue his education in Paris, where he studied piano with Santiago Riéra, composition with Nikolai Tcherepnin at the Russian Conservatoire and philosophy at the Sorbonne. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE LITHUANIAN CHORAL TRADITION: HISTORY, CONTEXT, EDUCATION, AND PRACTICE By INETA ILGUNAITĖ JONUŠAS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 © 2010 Ineta Ilgunaitė Jonušas 2 To the memory of Bronius Jonušas and his music “Heaven’s blessing earns he, who chooses music as his profession.” (Martin Luther) 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS When I left Lithuania, it was not so much to start a new life as to continue my old life, which revolved around music, in a new environment. I planned that I would attend an American university where I would continue my study of music and choral conducting to earn a master’s and doctoral degrees. My hope was to one day teach others to “make music” the way I had heard it most of my life in Lithuania. Now, after eight years of studying music in Lithuania and five years of graduate study in America, it seems that I have been blessed with the best of both worlds for having had the opportunity to learn from so many eminent Lithuanian and American “music makers.” In Lithuania, at the Vilnius Tallat-Kelpša Conservatory, while still a teenager, I was fortunate in being able to take my first lessons in conducting from Professor Vytautas Žvirblis, whose name will probably not mean much to anyone but the students who learned from his graceful hands. Later at the Lithuanian Academy of Music, I learned from Professor Vaclovas Radžiūnas, my major professor, and Jonas Aleksa, conductor of the Lithuanian State Opera. -

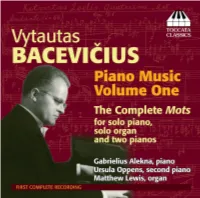

Toccata Classics TOCC 0134 Notes

1 3 6 2 7 9 1 3 6 7 9 2 2 2 7 9 P VYTAUTAS BACEVICIUSV AND HIS SEVEN MOTS by Malcolm MacDonald The Lithuanian composer Vytautas Bacevičius died in New York on 15 January 1970, having spent nearly half his life in exile. His name was almost unknown and few of his major works had been published or performed. Nowadays, by contrast, especially since the centenary celebrations in Kaunas and Vilnius in 2005, he is celebrated in Lithuania as one of the most original, and certainly the most radical and forward-looking, Lithuanian composers of the twentieth century. Bacevičius was born on 9 September 1905 in the Polish city of Łódź, into a cultured and highly musical family of joint Polish-Lithuanian origin. His father, Vincas Bacevičius, was a music-teacher from Lithuania who had married a Pole, Maria Modlínska. Their two boys and two girls grew up in Poland but often spent the summer in Lithuania. The best-known member of the family would be Bacevičius’ sister, the gifted Polish composer and violinist Grażyna Bacewicz (1909–69). While she remained in Poland with their mother, and adopted the Polish form of the family name, Bacevičius moved to Lithuania in 1926 to join his father, who had settled in Kaunas, which was the ‘provisional capital’ of Lithuania while Vilnius remained under Polish occupation. Bacevičius began composing at the age of nine and made his debut in concert in 1916 as both pianist and violinist. His first studies were in Łódź from 1919, including composition with Kazimierz Wilkomirski and Kazimierz Sikorski. -

Toccata Classics Cds Are Also Available in the Shops and Can Be Ordered from Our Distributors Around the World, a List of Whom Can Be Found At

Recorded in the Lithuanian National Philharmonic Hall on 8–9 October 2007 and 27–28 March 2009 Recording engineers: Michailas Omeljančukas (Nonet, Chamber Fantasy and String Quartet No. 3) and Vilius Kondrotas (Reflections) Mastering: Michailas Omeljančukas Booklet essay: Danutė Petrauskaitė, translated by Laima Servaitė and Veronika Janatjeva Design and layout: Paul Brooks, Design and Print, Oxford Executive producers: Eglė Grigaliūnaitė (Lithuanian Music Information and Publishing Centre) and Martin Anderson (Toccata Classics) Recording sponsored by The Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Lithuania TOCC 0169 © 2013, Toccata Classics, London P 2013, Toccata Classics, London Come and explore unknown music with us by joining the Toccata Discovery Club. Membership brings you two free CDs, big discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings and Toccata Press books, early ordering on all Toccata releases and a host of other benefits, for a modest annual fee of £20. You start saving as soon as you join. You can sign up online at the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com. Toccata Classics CDs are also available in the shops and can be ordered from our distributors around the world, a list of whom can be found at www.toccataclassics.com. If we have no representation in your country, please contact: Toccata Classics, 16 Dalkeith Court, Vincent Street, London SW1P 4HH, UK Tel: +44/0 207 821 5020 E-mail: [email protected] JERONIMAS KAČINSKAS: The pianist Daumantas Kirilauskas studied piano at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre, with Liucija Drąsutienė, and at the A LITHUANIAN RADICAL RECOVERED University Mozarteum Salzburg, with Karl-Heinz Kämmerling. -

Vytautas Bacevičius in New York

Non-promised Land: Vytautas Bacevičius in New York NON-PROMISED LAND: VYTAUTAS BACEVIčIUS IN NEW YORK Rūta Stanevičiūtė Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre Abstract: In the Lithuanian music of the twentieth century, one can clearly notice a cae- sura drawn by sociopolitical events which split the national culture in two parts both in terms of time and space. In the 1940s, most of the pre-war modernist composers appeared in exile. Graduates of the Paris, Berlin, and Prague Schools and founders of the ISCM Lithuanian Section who mainly settled down in the USA tried to adapt to the different musical and sociocultural reality which strongly affected the change in their creative orien- tations. Due to the broken relations with European centres of modern music, the conserva- tive cultural environment of Lithuanian emigrants and subsequent unsuccessful attempts to participate in the influential American music scene resulted in cultural isolation that significantly influenced the post-war music development, among others, that of composer and pianist Vytautas Bacevičius (1905–1970), the most prominent figure in Lithuanian emigration. An offspring of a mixed Lithuanian-Polish family and a representative of the Paris School moved to New York in 1940 and lived there as a refugee almost till the end of his life (he was granted citizenship as late as in 1967). Like many other European emigrant composers, being brought up in the cult of elitist art, he perceived egalitarian- ism of the American art as a personal menace. Since late 1950s, Bacevičius abandoned the strategies to adapt to American cultural environment and turned towards a unique conception of cosmic music, thus rethinking his early experiences of atonal music during the era of second avant-garde inspirations. -

Vytautas BACEVIČIUS Orchestral Works • 1 Piano Concertos Nos

Vytautas BACEVIČIUS Orchestral Works • 1 Piano Concertos Nos. 3 and 4 Spring Suite Gabrielius Alekna, Piano Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra Christopher Lyndon-Gee Vytautas Bacevičius (1905-1970) Orchestral Works • 1 The life of Vytautas Bacevičius is defined by exile. which he yearned as a native, Lithuania. He died on 15th He chose a first form of exile when, in 1926 at the age January, 1970, at the Queens Jewish Hospital, New York, of twenty-one, he left the Poland of his birth, his mother’s and is buried in the Cypress Hills cemetery in Queens. 1 country, abandoning the Polish style of his name, Witold, He had never loved America; from a vast correspondence, to accompany his Lithuanian-born father Vincas merely the letters that survive total 1,600, written on an (Wincenty) to the then-capital of Lithuania, Kaunas. He almost daily basis to his sisters and to various friends in almost immediately became a key figure in the musical Poland and Lithuania. They offer a vivid record of his life of this small nation, barely eight years after it was inability, unwillingness even, to lay down new roots in this re-established. alien land. He chose exile again when, in 1927, he began to Vytautas Bacevičius was born in Łódż, Poland on 9th spend substantial parts of each year in Paris, studying September, 1905, the second child of a Polish mother, piano with Santiago Riéra at the Russian Conservatoire Maria Modlińska (1871-1958) and her slightly younger that had been set up there by Nicolai Tcherepnin; the Lithuanian husband Vincas (1875-1952), his name latter became his composition teacher. -

Lietuvos Muzikologija 19.Indd

Lietuvos muzikologija, t. 19, 2018 Gražina DAUNORAVIČIENĖ Classes and Schools of Lithuanian Composers: A Genealogical Discourse Lietuvos kompozitorių klasės ir mokyklos: genealogijos diskursas Lietuvos muzikos ir teatro akademija, Gedimino pr. 42, LT-01110, Vilnius, Lietuva Email [email protected] Abstract The article addresses issues related to the development of the system for composition studies in Lithuania and beyond. Even though the ‘composition school’ notion has been featuring in musicological texts for quite some time, as a theoretical definition, it has received little reflection and conceptualisation. A study of different musicological texts shows that the notion is actually used to describe different phenom- ena and is not perceived differentially to this day. Theoretical discourse lacks in fundamental research aimed at uncovering the whole range of its meanings. This study is based on the hierarchical trinomial concept of the composition school proposed by Algirdas Jonas Ambrazas in his habilitation thesis entitled The Development of the Composition School of Juozas Gruodis and Other Lithuanian Composers (1991). The paper gives a brief historical and factual account of the emergence of the Lithuanian composition school. A particular focus is placed on the analysis of the creative approach and teaching methods of teachers associated with major Lithuanian composition classes and schools, namely Juozas Gruodis, Julius Juzeliūnas, Eduardas Balsys and Osvaldas Balakauskas. The relationship of these composition classes and schools with the national modernism idea articulated by Gruodis is investigated. The article delineates the difference between the two nonequivalent con- cepts, ‘composition class’ and ‘composition school’. From a genealogical point of view, the author defines two primary composition teaching schools – one of Gruodis and the other of Balakauskas – in the history of Lithuanian musical culture. -

SCANDINAVIAN, FINNISH & BALTIC CONCERTOS from the 19Th

SCANDINAVIAN, FINNISH & BALTIC CONCERTOS From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-H TORSTEIN AAGARD-NILSON (b.1964, NORWAY) Born in Oslo. He studied at the Bergen Conservatory and then taught contemporary classical music at this school. He has also worked as a conductor and director of music festivals. He has written works for orchestra, chamber ensemble, choir, wind and brass band. His catalogue also includes the following: Concerto for Cello and Orchestra (1995-6), Concerto for Trumpet and String Orchestra "Hommage" (1996), Trombone Concerto No. 1 (1998), Concerto for Euphonium and Orchestra "Pierrot´s Lament" (2000) and The Fourth Angel for Trumpet and Sinfonietta (1992-2000). Trombone Concerto No. 2 "Fanfares and Fairytales" (2003-5) Per Kristian Svensen (trombone)/Terje Boye Hansen/Malmö Symphony Orchestra ( + Hovland: Trombone Concerto, Amdahl: Elegy for Trombone, Piano and Orchestra and Plagge: Trombone Concerto) TWO-I 35 (2007) Tuba Concerto "The Cry of Fenrir" (1997, rev. 2003) Eirk Gjerdevik (tuba)/Bjorn Breistein/Pleven Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Koch: Tuba Concerto and Vaughan Williams: Tuba Concerto) LAWO CLASSICS LWC 1039 (2012) HANS ABRAHAMSEN (b. 1952, DENMARK) Born in Copenhagen. He played the French horn at school and had his first lessons in composition with Niels Viggo Bentzon. Then he went on to study music theory at The Royal Danish Academy of Music where his composition teachers included Per Nørgård and Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen. Later on, he had further composition studies with György Ligeti. In 1995, he was appointed assistant professor in composition and orchestration at The Royal Danish Academy of Music, Copenhagen. -

Experimentelle Musikkulturen in Mittelosteuropa Experimental Music Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe Sound Exchange

sound exchange sound exchange sucht nach den Wurzeln und der Gegenwart der experi mentellen Musik kulturen in Mittelosteuropa. Hier existiert eine lebendige, international vernetzte Szene von Musikern, Künstlern und Festivals. Jedoch sind lokale Traditionen und deren Protagonisten seit dem Umbruch 1989 teilweise in Vergessenheit geraten. sound Experimentelle Musikkulturen in Mittelosteuropa exchange will diese Traditionen sichtbar machen und zu aktuellen Experimental Music Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe Entwicklungen in den lokalen Musikszenen in Beziehung setzen. sound exchange embarks on a search for the roots and current state of experimental music cultures in Central and Eastern sound exchange Europe, which can boast a lively, internationally-linked scene of musicians, artists and festivals. Since the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, however, local traditions and their protagonists have partially been consigned to oblivion. sound exchange wants to ensure that these traditions can once again be seen, and position them in the context of current developments within local music scenes. ISBN 978-3-89727-487-7 Vertrieb distribution PFAU PFAU Herausgeber editors Carsten Seiffarth Carsten Stabenow Golo Föllmer 6 Vorwort 10 Preface Carsten Seiffarth / Carsten Stabenow 14 Grußwort: Goethe-Institut Prag 15 Welcome: Goethe-Institut Prague Angelika Eder 16 Grußwort: Kulturstiftung des Bundes 17 Welcome: The German Federal Cultural Foundation Hortensia Völckers / Alexander Farenholtz 18 Experiment und Widerstand – Experimentelle Musik