Transit-Oriented Development in the Chicago Region Efficient and Resilient Communities for the 21St Century CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lawrence to Bryn Mawr Modernization Project: Start of Stage a Construction

Lawrence to Bryn Mawr Modernization Project: Start of Stage A Construction Town Hall audience questions from March 2&4, 2021* meetings General questions Q. What does this project cost and how is it funded? A. The $2.1 billion RPM Phase One project is funded through a combination of federal and local funds including: $957 in federal Core Capacity funds (FTA); a federal $125 million Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) grant from the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP); $622 million in Transit TIF (tax-increment financing) funds from the City of Chicago; and CTA financing. Q. Are updates and notices available in languages other than English? A. Yes. We regularly provide subtitled recordings of past community meetings in Chinese, Spanish and Vietnamese, as well as translated flyers distributed to local community organizations. Additionally, we offer live translation services for public meetings upon request. Q. When will the block-by-block meetings happen? A. They will be scheduled for April 2021. We will notify the public when the dates are finalized. Q. When will the project start? A. Stage A construction is expected to begin Spring 2021. Once construction schedules are finalized, we will notify the public in advance of important construction start dates. Station design/station and track construction Q. Why won’t you have temporary stations at Lawrence and Berwyn? A. There is not enough space available to build temporary stations at those locations, unfortunately. Passengers who normally board at Lawrence can use Wilson or Argyle stations, which are each a quarter mile away and connected via the #36 Broadway bus, and Berwyn customers can use the Bryn Mawr or Argyle stations. -

Lawrence to Bryn Mawr Modernization Project Area

TRANSIT-ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT PLAN PRESENTATION LAWRENCE TO BRYN MAWR MODERNIZATION PROJECT AREA Purpose • Create a community-led vision for redevelopment in the neighborhood • Test specific concepts for CTA owned parcels • Expedite development post-construction Timing • Outgrowth of the community engagement process that began in 2009 • Planning Grant award from Federal Transit Administration • Coordination between transit project and development sites Transit-Oriented Development Plan Lawrence To Bryn Mawr Modernization Area Community Engagement 12 month process 22 stakeholder meetings including 3 open house meetings: • May 2017 – idea gathering • November 2017 – vision & goals; initial ideas • May 2018 – review of recommendations; next steps Aldermanic dialogue Website updates Transit-Oriented Development Plan Lawrence To Bryn Mawr Modernization Area TOD Planning Process TODAY Discovery Visioning Development Recommendations Implementation 2018 2020’s • Existing • Engagement • Concept • Public meeting • Select Conditions development developers • Vision • Final report • Market • Market testing • Zoning / Analysis • Principles and public review Goals • Engagement • Transit project • Construction coordination • Concept refinement • Aldermanic reviews Transit-Oriented Development Plan Lawrence To Bryn Mawr Modernization Area A Multi-Modal District Pedestrians • Enhanced pedestrian environment • Widened sidewalk on Hollywood Boulevard Transit • CTA Bryn Mawr, Berwyn, Argyle, and Lawrence stations • Increased transit service • #36, #81, #84, -

Village of Oak Park Lake Street Corridor Architectural Historical Survey

Village of Oak Park Lake Street Corridor Architectural Historical Survey Prepared by: Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. 330 Pfingsten Road Northbrook, Illinois 60062 (847) 272-7400 WJE Project No. 2005.4108 2 November 2006 Architectural Historical Survey Village of Oak Park Lake Street Corridor 2 FINAL FOR HPC REVIEW 2 November 2006 Village of Oak Park Lake Street Corridor Architectural Historical Survey PROJECT BACKGROUND In summer 2006, the Village of Oak Park began a planning and development study of the eastern Lake Street Corridor. The intent of the study is to solicit community input on the current status and perceived needs of the neighborhood; to provide a land use plan to guide future development on Lake Street; to assess the economic marketability of the Lake Street corridor; to promote mixed uses and pedestrian- oriented development; to assess parking needs and traffic; to identify economic limitations and funding strategies; to develop a character plan to guide future architectural and infrastructure design on the corridor; to identify zoning and regulatory changes needed to support desired development; and to identify buildings with historic character and significance that should be preserved during future redevelopment. This architectural historical survey addresses the last of these various goals established by the Village. Most but not all of the study area is included within the Ridgeland-Oak Park Historic District. The study area includes numerous contributing buildings for the district, as well as non-contributing contemporary structures. This architectural historical survey report has been developed as part of the overall planning study for the Lake Street corridor by Solomon Cordwell Buenz, Chicago, Illinois, scheduled for completion in December 2006. -

2017Chicago Transit Authority a Horse Drawn Omnibus, Originally Operated by the Citizen’S Line Circa 1853, Is Displayed at West Shops at Pulaski and Lake

HISTORICAL CALENDAR 2017Chicago Transit Authority A horse drawn omnibus, originally operated by the Citizen’s Line circa 1853, is displayed at West Shops at Pulaski and Lake. These early transit vehicles were quite primitive, barely just a notch above stagecoaches – little more than hard, wooden bench seats were provided on either side of very sparsely appointed coaches, with no heat, light, or other amenities. It is hard to believe that, from such humble beginnings, Chicago would one day have the second largest public transit system in North America, as it does today. January 2017 S M T W T F S B C D E F G A 1 New Year’s Day 2 3 4 5 6 7 A B C D E F G 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 G A B C D E F Martin Luther 15 16 King, Jr. Day 17 18 19 20 21 F G A B C D E 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 E F G ABCDEFG: December 2016 February 2017 CTA Operations S M T W T F S S M T W T F S Division 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 Group Days Off 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 t Alternate day off if 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 you work on this day 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 29 30 31 l Central offices closed 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 26 27 28 Chicago streetcar #225 is outside of the 77th Street carbarn, sporting an early Chicago Transit Authority emblem but still wearing the red and cream color scheme of its predecessor company, the Chicago Surface Lines. -

Chicago & West Towns Railways, Inc

INSPIICTION TRIP CHICAGO & WEST TOWNS RAILWAYS, INC. (j SUNDAY, APRIL 23rd, 1939 Z ITINER~RY of TRIP 12:00 noon Depart in special cars of 139 type from C&WT terminal at 22nd & Kenton opposite Hawthorne Works, Western Electric Co. 1:00 p.m. Arrive LaGrange station, stopping en route in Riverside, at Desplaines River, Brookfield and LaGrange Park to photograph special cars in typical backgrounds. 1:25 p.m. Arrive Harlem barn to inspect and photograph shops and rolling stock, including line car 15 made of old passenger car. 2:05 p.m. Leave barns and proceed to 52nd Avenue, cross to Chicago Ave., car route and then to Roosevelt, west over joint track with Chicago Surface Lines to Austin and on to Desplaines Ave., north along regular route, stopping at typical residential background for photographs, to Lake Street and east to the Lake Street barn. </) 3:00 p.m. Arrive Lake st. barn and inspect and photograph equipment, including old power plant. Z 3:45 p.m. Leave Lake Street barn, retracing route to 22nd, then east to Kenton Avenue. 4:30 p.m. Arrive Kenton Ave., terminal, and leave special cars. ~ The above times are approximate and will be varied from as conditions l- may require. I (j) L :5 o o ~ u r u ~l:i'llITI:14.L I:LI:CTI:1IC 1:>4.1 LI'4.i'llIS~ ASS()CI4.TI()i'llI CIiIC4(;V. ILLINVIS BULLETIN NUMBER THREE April, 1939 ©1939, 2008 Central Electric Railfans' Association 1 www.cera-chicago.org Bulletin lUmber !hree of the Central Electric Railfans' A8sociation (Division of the national Electric Railroaders' Association, ••Y.) Duplicate copie8 8&7 be ,ecured at 15~ each by addre88ing OmRA , at 1240 idhon Building, Ohicqo OHIOAGO I WEST TOWNS RAILWAYS. -

Chicago Transit Authority (CTA)

06JN023apr 2006.qxp 6/21/2006 12:37 PM Page 1 All Aboard! Detailed Fare Information First Bus / Last Bus Times All CTA and Pace buses are accessible X to people with disabilities. This map gives detailed information about Chicago Transit # ROUTE & TERMINALS WEEKDAYS SATURDAY SUNDAY/HOL. # ROUTE & TERMINALS WEEKDAYS SATURDAY SUNDAY/HOL. # ROUTE & TERMINALS WEEKDAYS SATURDAY SUNDAY/HOL. Authority bus and elevated/subway train service, and shows Type of Fare* Full Reduced Reduced fares are for: You can use this chart to determine days, hours and frequency of service, and Fare Payment Farareboebox Topop where each route begins and ends. BROADWAY DIVISION ILLINOIS CENTER/NORTH WESTERN EXPRESS Pace suburban bus and Metra commuter train routes in the 36 70 Division/Austin east to Division/Clark 4:50a-12:40a 5:05a-12:40a 5:05a-12:40a 122 CASH FARE Accepted on buses only. $2 $1 Devon/Clark south to Polk/Clark 4:00a-12:10a 4:20a-12:00m 4:20a-12:15a Canal/Washington east to Wacker/Columbus 6:40a-9:15a & CTA service area. It is updated twice a year, and available at CTA Children 7 through 11 BUSES: CarCardsds It shows the first and last buses in each direction on each route, traveling Polk/Clark north to Devon/Clark 4:55a-1:20a 4:55a-1:05a 4:50a-1:15a Division/Clark west to Division/Austin 5:30a-1:20a 5:40a-1:20a 5:45a-1:20a 3:40p-6:10p Exact fare (both coins and bills accepted). No cash transfers available. years old. -

List of Illinois Recordations Under HABS, HAER, HALS, HIBS, and HIER (As of April 2021)

List of Illinois Recordations under HABS, HAER, HALS, HIBS, and HIER (as of April 2021) HABS = Historic American Buildings Survey HAER = Historic American Engineering Record HALS = Historic American Landscapes Survey HIBS = Historic Illinois Building Survey (also denotes the former Illinois Historic American Buildings Survey) HIER = Historic Illinois Engineering Record (also denotes the former Illinois Historic American Engineering Record) Adams County • Fall Creek Station vicinity, Fall Creek Bridge (HABS IL-267) • Meyer, Lock & Dam 20 Service Bridge Extension Removal (HIER) • Payson, Congregational Church, Park Drive & State Route 96 (HABS IL-265) • Payson, Congregational Church Parsonage (HABS IL-266) • Quincy, Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, Freight Office, Second & Broadway Streets (HAER IL-10) • Quincy, Ernest M. Wood Office and Studio, 126 North Eighth Street (HABS IL-339) • Quincy, Governor John Wood House, 425 South Twelfth Street (HABS IL-188) • Quincy, Illinois Soldiers and Sailors’ Home (Illinois Veterans’ Home) (HIBS A-2012-1) • Quincy, Knoyer Farmhouse (HABS IL-246) • Quincy, Quincy Civic Center/Blocks 28 & 39 (HIBS A-1991-1) • Quincy, Quincy College, Francis Hall, 1800 College Avenue (HABS IL-1181) • Quincy, Quincy National Cemetery, Thirty-sixth and Maine Streets (HALS IL-5) • Quincy, St. Mary Hospital, 1415 Broadway (HIBS A-2017-1) • Quincy, Upper Mississippi River 9-Foot Channel Project, Lock & Dam No. 21 (HAER IL-30) • Quincy, Villa Kathrine, 532 Gardner Expressway (HABS IL-338) • Quincy, Washington Park (buildings), Maine, Fourth, Hampshire, & Fifth Streets (HABS IL-1122) Alexander County • Cairo, Cairo Bridge, spanning Ohio River (HAER IL-36) • Cairo, Peter T. Langan House (HABS IL-218) • Cairo, Store Building, 509 Commercial Avenue (HABS IL-25-21) • Fayville, Keating House, U.S. -

Chicago Transit Authority, Under the Supervision of the Director of Subject of "Communities We Serve" in This Issue, Is the Lake Public Informotion

T R ~ ~ S • T ~ E \IV S FEBRU ARY, 1965 119 Employes Collect $1,190 in 1964 Suggestion Awards A TOTAL of $1,190.00 in cash awards was shared by 119 CTA employes whose ideas paid off when submitted for consideration by the Employe Sug- gestion Committee during 1964, according to the annual report released recently. The awards were given to 110 employes whose original suggestions were selected and placed in operation during the year, and nine employes re- ceived supplementary awards for suggestions adop- ted previously which had been tested in actual op- erations for one year and, after revaluation, prov- ed worthy of an additional award. Winners of the original awards received $1 ,050.00 in cash grants and $140.00 was divided by winners of supplementary awards, averaging out at $9.55 each for original award and $15.56 each for sup- plementary award. Of the total 1, 629 sugge stions submitted during The report pointed out that of the 1,629 sugges- the year, 811 or 50 per cent were accepted for tions received during the year, 811 were found evaluation. worthy of consideration and were given incentive prizes consisting of their choice of a Paper Mate Shops and Equipment personnel again received pen, men's or ladies' wallet, Zippo lighter, or a a major share of the awards, collecting 54 for a tote bag. In addition many will win a cash award total of $585.00. General Office employes were if their idea prove s workable. credited with winning 31 awards for a total of $195.00. -

2021 Historical Calendar Cta 2021 January

cta 2021 Historical Calendar cta 2021 January Built in 1936 by the St. Louis Car Company, Chicago Surface Lines trolley bus #184 heads eastbound via Diversey to Western. Trolley bus service was first introduced in Chicago on the #76 Diversey route in 1930. Other trolley bus routes were soon added, some as extensions of existing streetcar lines and later as conversions of streetcar lines to trolley bus service. Trolley bus extensions to existing streetcar lines were an economical way to serve new neighborhoods that were established in outlying parts of the city. Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat ABCDEFG: December 2020 February 2021 B C CTA Operations S M T W T F S S M T W T F S Division 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 Group Days Off 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 t Alternate day off if 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 you work on this day 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 l Central offices closed 27 28 29 30 31 28 1 New Year’s Day 2 C D E F G A B 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 B C D E F G A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 A B C D E F G Martin Luther King, 17 18 Jr. Day 19 20 21 22 23 G A B C D E F 24 F 31 25 26 27 28 29 30 cta 2021 February Car #1643 was an example of Chicago’s first electric streetcars. -

HISTORICAL CALENDAR Added Historical Notes Follow Calendar

2020 HISTORICAL CALENDAR Added historical notes follow calendar Chicago Transit Authority JANUARY 2020 After a snow in December 1951, CTA streetcar #4231 is making its way down Halsted to its terminus at 79th Street. Built in 1948 by the Pullman Company in Chicago, car #4231 was part of a fleet of 600 Presidents Conference Committee (PCC) cars ordered by Chicago Surface Lines (CSL) just before its incorporation into the Chicago Transit Authority. At 48 feet, these were the longest streetcars used in any city. Their comfortable riding experience, along with their characteristic humming sound and color scheme, earned them being nicknamed “Green Hornets” after a well-known radio show of the time. These cars operated on Chicago streets until the end of streetcar service, June 21, 1958. Car #4391, the sole survivor, is preserved at the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, IL. SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT ABCDEFG: December 2019 February 2020 C D E F CTA Operations S M T W T F S S M T W T F S Division 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 Group Days Off 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 t Alternate day off if 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 you work on this day 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 l Central offices closed 1 New Year’s Day 2 3 4 F G A B C D E 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 E F G A B C D 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 D E F G A B C Martin Luther 19 20 King, Jr. -

The Railway Age

118 The Railway age February 13, 1901. A TYPICAL SUBURBAN SERVICE. beautiful north shore, and will continue to demand frequent increase of transportation facilities. While the Northwestern is Chicago How the Sc Northwestern Carries the Rural Residents to already paralleled by an electric line to Waukegan and beyond and from Chicago. and also has the competition of another steam line as far as "Wells street station: Do not forget your umbrellas and Evanston, it is sure of a heavy increase in its patronage all parcels." This is the cheerful announcement and admonition along the lake shore, and its management, judging from the that salutes the ears of the 17,000 or more passengers who arrive Improvements which It is continually making, lias no fear about dally at the Chicago terminus of the Chicago & Northwestern competition In that direction. Railway on the trains, more than 125 in number, that bring THE WELLS 8TRRKT TERMINALS. suburban travel over the three divisions from the North, the Looking at the suburban train service of the Northwestern Northwest and the West. And Wells street station is a busy from an operative standpoint, one is at first impressed with spot— none more so in Chicago— as the incoming thousands meet admiration for the skill with which the immense move an equal number of outgoing thousands, and the 259 trains roll ment of trains, through as well as suburban, freight as well In and out on their appointed tracks and times, as if moved as passenger, is handled along the narrow throat of two pairs by gigantic clockwork, through the day and night. -

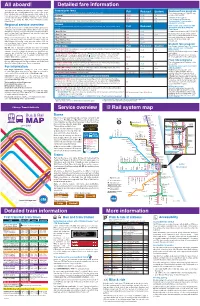

First Bus All Aboard! Rail System Map Detailed Fare in for Ma Tion Service

All aboard! Detailed fare in for ma tion First bus / last bus times This map gives detailed information about Chica go Transit Base/regular fares All CTA and Pace buses are accessible to people with disabilities. # ROUTE & TERMINALS WEEKDAYS SATURDAY SUN./HOL. # ROUTE & TERMINALS WEEKDAYS SATURDAY SUN./HOL. # ROUTE & TERMINALS WEEKDAYS SATURDAY SUN./HOL. Authority bus and el e vat ed/sub way train ser vice, and shows Full Reduced Student Reduced fare program X Pay-per-ride fares, as deducted from value in a Ventra Transit Account Use this chart to determine days, hours of service, where each Pace subur ban bus and Metra commut er train routes in the The following groups are eligible to pay a reduced fare on CTA: CTA ser vice area. It is up dat ed regularly, and avail able at ‘L’ train fare $2.50* $1.25 75¢ route begins and ends, and first and last buses in each direction Wallace/Racine West Lawrence Inner Drive/Michigan Express 44 Racine/87th north to Halsted (Orange) 4:30a-9:40p 8:00a-6:00p 9:00a-6:00p 81W Cumberland (Blue) east to Jeff Park (Blue) 5:25a-10:25p 5:20a-10:20p 8:45a-10:15p 14 6 Berwyn (Red) south to Museum Campus 5:55a-10:40p 6:00a-10:40p 6:00a-10:40p † on each route. X X X CTA rail stations, Metra down town terminals, visitor cen ters, Bus fare $2.25 $1.10 75¢ Children 7 through 11 Halsted (Orange) south to Racine/87th 5:15a-10:25p 8:50a-6:45p 9:45a-6:45p Museum Campus north to Berwyn (Red) 7:00a-11:35p 6:50a-11:40p 6:50a-11:35p X Jeff Park X (Blue) west to Cumberland X (Blue) 4:55a-9:55p 4:50a-9:50p 8:20a-9:50p air ports, or by calling the RTA.