Connecting Thread

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Machine Embroidery Threads

Machine Embroidery Threads 17.110 Page 1 With all the threads available for machine embroidery, how do you know which one to choose? Consider the thread's size and fiber content as well as color, and for variety and fun, investigate specialty threads from metallic to glow-in-the-dark. Thread Sizes Rayon Rayon was developed as an alternative to Most natural silk. Rayon threads have the soft machine sheen of silk and are available in an embroidery incredible range of colors, usually in size 40 and sewing or 30. Because rayon is made from cellulose, threads are it accepts dyes readily for color brilliance; numbered unfortunately, it is also subject to fading from size with exposure to light or frequent 100 to 12, laundering. Choose rayon for projects with a where elegant appearance is the aim and larger number indicating a smaller thread gentle care is appropriate. Rayon thread is size. Sewing threads used for garment also a good choice for machine construction are usually size 50, while embroidered quilting motifs. embroidery designs are almost always digitized for size 40 thread. This means that Polyester the stitches in most embroidery designs are Polyester fibers are strong and durable. spaced so size 40 thread fills the design Their color range is similar to rayon threads, adequately without gaps or overlapping and they are easily substituted for rayon. threads. Colorfastness and durability make polyester When test-stitching reveals a design with an excellent choice for children's garments stitches so tightly packed it feels stiff, or other items that will be worn hard stitching with a finer size 50 or 60 thread is and/or washed often. -

Schmetz Needle Guide

NEEDLE GUIDE Needle Anatomy Butt: The beveled end allows easy insertion in the needle bar. Shank: Household needles have a flat shank, while commercial and industrial needles have round, threaded, notched or other special shanks. Shanks allow perfect positioning of the needle in the sewing machine needle bar. Shoulder: The sloping area transitioning between the shank and blade. Schmetz color codes appear on the shoulder. Blade: Needle size is determined by the blade diameter (i.e., size 75 is .75mm) Groove: The groove cradles and guides thread to the eye. The length and size of the groove vary according to needle type. Scarf: The indentation above the eye that allows the bobbin hook to smoothly grab the thread under the throat plate to create a stitch. The shape and size of the scarf vary according to needle type. Eye: The hole through which thread passes. The shape and size of the eye vary according to needle type. Point and Tip: Length, shape and size vary according to needle types. Change Your Needle 130/705 H Damaged or worn needles result in: Household sewing machines require a needle with a flattened shank. All needles in this system have a flattened shank for perfect needle • Broken or shredded threads positioning in the needle bar in relation to the hook. • Skipped stitches • Puckered fabrics • Damaged fabrics Schmetz Works with All Sewing Machines! • Uneven threads Schmetz needles work with all new, current and older household sewing machines! Replace Your Needle It’s the easiest way to How to Read a Needle Package improve your stitch quality. -

Thread Yarn and Sew Much More

Thread Yarn and Sew Much More By Marsha Kirsch Supplies: • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Yarn embellishment foot set 920403096 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® 7 hole cord foot with threader 412989945 • HUSQVARNA VIKING ® Clear open toe foot 413031945 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Clear ¼” piecing foot 412927447 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Embroidery Collection # 270 Vintage Postcard • HUSQVARNA VIKING® Sensor Q foot 413192045 • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER™ Royal Hoop 360X200 412944501 • INSPIRA® Cut away stabilize 141000802 • INSPIRA® Twin needles 2.0 620104696 • INSPIRA® Watercolor bobbins 413198445 • INSPIRA® 90 needle 620099496 © 2014 KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. VIKING, INSPIRA, DESIGNER and DESIGNER DIAMOND ROYALE are trademarks of KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. HUSQVARNA is a trademark of Husqvarna AB. All trademarks used under license by VSM Group AB • Warm and Natural batting • Yarn –color to match • YLI pearl crown cotton (color to match yarn ) • 2 spools of matching Robison Anton 40 wt Rayon thread • Construction thread and bobbin • ½ yard back ground fabric • ½ yard dark fabric for large squares • ¼ yard medium colored fabric for small squares • Basic sewing supplies and 24” ruler and making pen Cut: From background fabric: 14” wide by 21 ½” long From dark fabric: (20) 4 ½’ squares From medium fabric: (40) 2 ½” squares 21” W x 29” L (for backing) From Batting 21” W x 29” L From YLI Pearl Crown Cotton: Cut 2 strands 1 ¾ yds (total 3 ½ yds needed) From yarn: Cut one piece 5 yards © 2014 KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. VIKING, INSPIRA, DESIGNER and DESIGNER DIAMOND ROYALE are trademarks of KSIN Luxembourg ll, S.ar.l. HUSQVARNA is a trademark of Husqvarna AB. All trademarks used under license by VSM Group AB Directions: 1. -

Stress Relaxation of Elastomeric Orthodontic Thread

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1976 Stress Relaxation of Elastomeric Orthodontic Thread Robert Theodore Bergman Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Bergman, Robert Theodore, "Stress Relaxation of Elastomeric Orthodontic Thread" (1976). Master's Theses. 2851. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/2851 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1976 Robert Theodore Bergman STRESS RELAXATION OF ELASTOMERIC ORTHODONTIC THREAD by Robert T. Bergman, B. A., D. D.S. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science June 1976 -- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Dr. James L. Sandrik, for his advice and continued guidance which provided me with a sincere appreciation of investigative principles during the work on my thesis. I gratefully acknowledge Marie Feng whose assistance and advice helped during the preparation of this thesis. I acknowledge Dr. Milton Braun for his guidance and interest during my years of graduate work. I also wish to thank John Cheng for all the help he gave me in the processing of the statistics for this thesis. ii -- VITA Robert Theodore Bergman was born on April 6, 1942 in Los Angeles, California. -

OT Fact Sheet: Sewing Thread

Sewing Thread – Textile and Wearing Apparel Overview This provision refers to articles of clothing in Chapters 61 and 62 that must be assembled using sewing thread of the Parties to the Agreement. The provision applies to the component that determines the tariff classification of the good and such component must satisfy the tariff change requirements set out in the rule for that good. This is a new provision under the new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and there is no such provision in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Processing: sewing thread is considered formed and finished in the territory of one or more Parties if all production processes and finishing operations, starting with the extrusion of filaments, strips, film or sheet, and including slitting a film or sheet into strip, or the spinning of all fibers into yarn, or both, and ending with the finished single or plied thread ready for use for sewing without further processing, took place in the territories of one or more of the USMCA countries even if non-originating fiber is used in the production of sewing thread of heading 52.04, 54.01 or 55.08, or yarn of heading 54.02 used as sewing thread References • USMCA • NAFTA o Final Text: Chapter 4, Annex 4-B, Section XI o No provision. o HTSUS: Chapter 61, Note 3 and Chapter 62, Note 4 o General Note 11 Significant Changes in USMCA Provision USMCA NAFTA Sewing New provision in USMCA. • No provision. Thread • An article of apparel or clothing accessory of Chapter 61 or Chapter 62 that contains sewing thread of headings 52.04 (cotton), 54.01 (man-made filaments), or 55.08 (man-made staple fiber), or yarn of heading 54.02 (synthetic filament yarn) used as sewing thread shall be considered FACT SHEET SHEET FACT originating only if such sewing thread is both formed and finished in the territory of one or more of the Parties. -

Sewing Focus Umbrellas

S EWING F OCUS TECHNICAL SEWING INFORMATION Umbrellas Checklist for Sewing Umbrellas Sewing Parameters: SCHMETZ Tip: Needle size NM SIZE 70 – 110 10 – 18 Depending on the thickness of the material. We recommend the use of the SCHMETZ SERV 7 needle. Needle point In the production of umbrellas, mostly round points of the type “R” and “SPI” are used. Sewing thread In the production of umbrellas, mostly core spun threads made from cotton or polyester are used. They have a core multi filament made from polyester and thus have greater strength. These threads are also available with hydrophobic finishing. Machine Many processes are carried out using industrial high-speed sewing machines with stitch types 301 (double lockstitch) and types of overedge chain stitches (class 500). Several types of automats are also used. Other factors: Thread tension The required thread tension depends on fabric, sewing thread and sewing machine. It should however be kept as low as possible in order to avoid seam puckering. Stitch type Double lockstitch (stitch type 301), single thread chain stitch (stitch type 101) and types of overedge chain stitch (class 500); all stitch types and classes according to DIN 61400. Stitch density The higher the stitch density the higher the elasticity and strength of the seam. The production of umbrellas requires an extremely high stitch density of 7 stitches/cm for the seam to withstand the high tension. Sewing Focus TECHNICAL SEWING INFORMATION Quick Reference for Typical Sewing Problems in Umbrella Manufacturing Symptoms Effect -

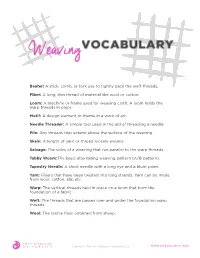

A Long, Thin Thread of Material Like Wool Or Cotton. a Machine Or Frame

Weaving A stick, comb or fork used to tightly pack the weft threads. A long, thin thread of material like wool or cotton. Beater: A machine A stick, or frame comb, used or fork for useweaving to tightly cloth. pack A loom the weftholds threads. the warp threads in place. Fiber: A long, thin thread of material like wool or cotton. A design element or theme in a work of art. Loom: A machine or frame used for weaving cloth. A loom holds the warp threads A in simple place. tool used in the aid of threading a needle. A design element or theme in a work of art. AnyMotif: threads that extend above the surface of the weaving. Needle Threader: A simple tool used in the aid of threading a needle. A length of yarn or thread loosely wound. Pile: Any threads that extend above the surface of the weaving. The sides of a weaving that run parallel to the warp threads. Skein: A length of yarn or thread loosely wound. The basic alternating weaving pattern (A/B pattern). Selvage: The sides of a weaving that run parallel to the warp threads. A short needle with a long eye and a blunt point. Tabby Weave:The basic alternating weaving pattern (A/B pattern). Fibers that have been twisted into long strands. Yarn can be made from wool, cotton,Tapestry silk, Needle: etc. A short needle with a long eye and a blunt point. Yarn: In weaving, Fibers thatthe verticalhave been threads twisted held into in placelong strands. on a loom Yarn that can form be madethe foundationfrom wool,of a fabric. -

Buttons & Buttonholes

CT-MMB.189 BUTTONS & BUTTONHOLES BUTTONS Selection Button selection depends on the type and style Buttons can be fascinating, functional, and of the garment. Buttons should be selected fashionable. They are fascinating because of their BEFORE making buttonholes or button loops. many sizes, shapes, colors, and designs. They are Consider the following when making your functional because they are one of the major selection: methods of opening and closing garments. Buttons are fashionable because they also decorate and $ The pattern will have a suggested size which enhance apparel & other items. was determined as the pattern was being made. If the button size is changed, so must the size of the button and buttonhole placket. $ Weight of fabric B Heavy fabric needs heavier and larger buttons; lighter fabric needs lighter and smaller buttons. $ Fabric design B Buttons can blend with the History fabric OR they can call attention to the area. The term is from the French word, bouton, To call attention to the area use solid colored meaning a round object. Since the 13th century, buttons on prints and patterned buttons on buttons have been used as fasteners. Before that, solid color fabrics. they were used more for their decorative and symbolic value. Today, buttons continue to be used as decoration, but their placement once served a useful purpose. For instance buttons on the back of men’s coats served as a way to fasten coat tails up out of the $ Use a smooth, flat-textured button on smooth way when riding on horseback. During Frederick textured fabrics. Shiny buttons are best on the Great=s reign, it was customary for three decorative, shiny fabrics. -

Troubleshooting Embroidery Designs Written By: Kay Hickman, BERNINA Educator, Professional & Home Embroidery Specialist

BERNINA eBook Series JUST EMBROIDER IT! Troubleshooting Embroidery Designs Written by: Kay Hickman, BERNINA Educator, Professional & Home Embroidery Specialist Qualities of a Good Design § Maintenance Proper Setup § Problem / Solution Scenarios § Pressing Matters There is nothing quite as satisfying as stitching a perfect embroidery design for that special project. But it can also be frustrating when things go wrong. In order to troubleshoot and fix embroidery design problems, we need to first understand the qualities of a good design and how preventative maintenance can prevent a lot of issues from occurring in the first place. QUALITIES OF A GOOD DESIGN • The fabric is smooth and pucker-free around the outer edges of the design. • There are no traces of the bobbin thread showing on the top side. • There is no gapping between individual elements of a design or between the fill stitches and the design outlines. BACK SIDE • On the back (bobbin) side, you should see the bobbin thread. You should also see the needle threads around the edges of a fill or either side of a column type design. FRONT SIDE MAINTENANCE Preventative maintenance can go a long way to aid in getting a good stitch out. • Clean the machine every 3 to 4 hours of stitching time. This is especially crucial because the high speed of the embroidery creates more lint and fuzz than you encounter during normal sewing. Remove BEFORE HOOK OIL AFTER HOOK OIL all fuzz and check for tiny bits of thread that might • Follow the manufacturer’s suggestions and take be stuck in the bobbin case. -

Sewing Basics - Know Your Needles by Nancy Fiedler

Sewing Basics - Know Your Needles By Nancy Fiedler Whether you have a top-of-the-line sewing machine or an economy model, the most important tool used is the sewing machine needle. The sewing life of a needle is 8 hours. In that time, the point will become worn and stitch quality may become compromised. Keep a variety of needles on-hand to change regularly. A good rule of thumb is to use a new needle at the start of every project. The type and size of needle to use is determined by: • Thread type: polyester, cotton, rayon or metallic • Thread weight: 12wt, 30wt, 40wt, 60wt, 90wt (The higher the number, the finer the thread.) • Fabric type: knit, woven, densely woven, specialty • Technique: general sewing, embroidery, embellishing or quilting Take a look at the anatomy of a needle: www.janome.com Page 1 Sewing Basics - Know Your Needles A sewing machine needle is made of six parts: 1. The Shank is the upper portion of the needle, which is inserted into the sewing machine. The shank on a needle for domestic sewing has a flat back. This needle system is indicated on some packaging by these notations: HA x 1, 15 x 1 or 130/705. 2. The Shaft is the entire lower portion of the needle. The size of the needle is determined by the diameter of the shaft. The smaller the number, the smaller the shaft will be. The eye will increase in size proportionately to the size of the shaft. 3. The Groove is on the front of the needle. -

Juki MOL-254

AUTOMATIC 2-NEEDLE BELT-LOOP ATTACHING MACHINE MOL-254 Shortened machine time and consistent loop feeding help increase productivity. MOL-254 (equipped with full options) MACHINE TIME 1.2 SEC./BELT-LOOP The machine time is 1.2 seconds per belt-loop (with 28 stitches). The new machine head specifically developed for belt-loop attaching machines runs at a maximum sewing speed of 2,500rpm and is equipped with a direct-drive system that improves start up performance and shortens sewing time. The belt-loop feeding device is now provided with a halfway standby capability for subsequent belt-loops, and its faster belt-loop supply action shortens the time required for supplying belt-loops and helps speed up the machine time to 1.2 seconds per belt-loop (with 28 stitches). With the improved consistency in belt-loop supply action and re-try capability, the machine down time is substantially reduced. Belt-loops are fed out by the conventional gear-roller feeding mechanism and also drawn out by the new drawing mechanism on the clamp device. Supported by these two mechanisms, the folding fork catches “curled” or “creased” belt-loops every time and supplies them to the head. In addition, the sensor of the clamp device detects the presence/absence of belt-loops. If it detects a faulty belt-loop feed, the clamp device automatically repeats the clamping action. Since the operator doesn't have to operate the set-back switch, less time is lost. ●When feeding out belt-loops ●When the finger catches belt-loops The machine quickly and reliably disposes splices without any delays in cycle time. -

Sewing Stretch Knit Fabrics

TECHNICAL BULLETIN Sewing Stretch Knit Fabrics Most stretch knit garments are seamed with overedge and/or coverstitch seam constructions because these stitches offer the best seam elasticity and coverage of the raw edge of the fabric. A quality problem that is common with stretch knits is excessive “broken stitches” or “stitch cracking” when the seam is stretch excessively. Generally the greater the elasticity of the fabric, i.e., higher Lycra® or Spandex® content, the more likely you are to have broken stitches if you do not understand how to optimize elasticity in the seam. WHAT CAN BE DONE TO MINIMIZE BROKEN STITCHES? Most broken stitches are the result of one of the following: - Not using the correct thread type & size - Not having enough stitches per inch - Not sewing with the correct stitch balance or machine thread tensions set incorrectly - Not using the correct seam margin or needle spacing for the application WHAT THREAD TYPE & SIZE ARE COMMONLY USED TO SEW STRETCH KNIT FABRICS? The most common threads used to sew stretch knit fabrics are textured polyester or textured nylon threads like A&E’s Wildcat® Plus or Best Stretch®. Textured threads are ideal for overedge and coverstitch seams because they offer excellent seam coverage and seam elasticity. In cases where performance garments will be subjected to harsh end-use applications and wash cycles, many manufacturers prefer to use Perma Core® threads in the needles and textured threads in the looper positions. Spun polyester threads such as A&E’s Perma Spun® and Excell® are also used to reduce thread cost.