Current Sociology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clothing Fantasies: a Case Study Analysis Into the Recontextualization and Translation of Subcultural Style

Clothing fantasies: A case study analysis into the recontextualization and translation of subcultural style by Devan Prithipaul B.A., Concordia University, 2019 Extended Essay Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication (Dual Degree Program in Global Communication) Faculty of Art, Communication and Technology © Devan Prithipaul 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2020 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Devan Prithipaul Degree: Master of Arts Title: Clothing fantasies: A case study analysis into the recontextualization and translation of subcultural style Program Director: Katherine Reilly Sun-Ha Hong Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor ____________________ Katherine Reilly Program Director Associate Professor ____________________ Date Approved: August 31, 2020 ii Abstract Although the study of subcultures within a Cultural Studies framework is not necessarily new, what this research studies is the process of translation and recontextualization that occurs within the transnational migration of a subculture. This research takes the instance of punk subculture in Japan as a case study for examining how this subculture was translated from its original context in the U.K. The frameworks which are used to analyze this case study are a hybrid of Gramscian hegemony and Lacanian psychoanalysis. The theoretical applications for this research are the study of subcultural migration and the processes of translation and recontextualization. Keywords: subculture; Cultural Studies; psychoanalysis; hegemony; fashion communication; popular communication iii Dedication Glory to God alone. iv Acknowledgements “Ideas come from pre-existing ideas” was the first phrase I heard in a university classroom, and this statement is ever more resonant when acknowledging those individuals who have led me to this stage in my academic journey. -

Willieverbefreelikeabird Ba Final Draft

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Japanskt mál og menning Fashion Subcultures in Japan A multilayered history of street fashion in Japan Ritgerð til BA-prófs í japönsku máli og menningu Inga Guðlaug Valdimarsdóttir Kt: 0809883039 Leðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorkellsdóttir September 2015 1 Abstract This thesis discusses the history of the street fashion styles and its accompanying cultures that are to be found on the streets of Japan, focusing on the two most well- known places in Tokyo, namely Harajuku and Shibuya, as well as examining if the economic turmoil in Japan in the 1990s had any effect on the Japanese street fashion. The thesis also discusses youth cultures, not only those in Japan, but also in North- America, Europe, and elsewhere in the world; as well as discussing the theories that exist on the relation of fashion and economy of the Western world, namely in North- America and Europe. The purpose of this thesis is to discuss the possible causes of why and how the Japanese street fashion scene came to be into what it is known for today: colorful, demiurgic, and most of all, seemingly outlandish to the viewer; whilst using Japanese society and culture as a reference. Moreover, the history of certain street fashion styles of Tokyo is to be examined in this thesis. The first chapter examines and discusses youth and subcultures in the world, mentioning few examples of the various subcultures that existed, as well as introducing the Japanese school uniforms and the culture behind them. The second chapter addresses how both fashion and economy influence each other, and how the fashion in Japan was before its economic crisis in 1991. -

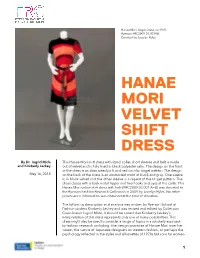

Hanae Mori Velvet Shift Dress

Hanae Mori Target Dress, ca.1970. Ryerson FRC2009.03.001AB. Donated by Jocelyn Ryles. HANAE MORI VELVET SHIFT DRESS By Dr. Ingrid Mida This Hanae Mori shift dress with stand collar, short sleeves and belt is made and Kimberly Leckey out of velvet and is fully lined in black polyester satin. The design on the front of the dress is an abstracted pink and red circular target pattern. The design May 16, 2014 on the back of the dress is an abstracted motif of black and gray. One sleeve is in black velvet and the other sleeve is a repeat of the target pattern. The dress closes with a back metal zipper and two hooks and eyes at the collar. This Hanae Mori velvet shift dress with belt (FRC2009.03.001 A+B) was donated to the Ryerson Fashion Research Collection in 2009 by Jocelyn Ryles. No other provenance information was obtained at the time of donation. The following description and analysis was written by Ryerson School of Fashion student Kimberly Leckey and was revised and edited by Collection Coordinator Ingrid Mida. It should be noted that Kimberly Leckey’s interpretation of this dress represents only one of many possibilities. This dress might also be used to consider a range of topics in a scholarly approach to fashion research including: the design practices of Hanae Mori over her career, the nature of Japanese designers on western fashion, or perhaps the psychology reflected in the styles and silhouettes of 1970s fashions for women. 1 Hanae Mori DESCRIPTION Target Dress, The dress is sewn together with black polyester thread and the inside seams ca.1970. -

Tokyo Orientation 2017 Ajet

AJET News & Events, Arts & Culture, Lifestyle, Community TOKYO ORIENTATION 2017 Stay Cool and Look Clean - how to be fashionably sweaty Find the Fun - how to get involved with SIGs (and what they exactly are) Studying Japanese - how to ganbaru the benkyou on your sumaho Shinju-who? - how to have fun and understand Shinjuku Hot and Tired in Tokyo - how to spend those orientation evenings The Japanese Lifestyle & Culture Magazine Written by the International Community in Japan1 CREDITS & CONTENT HEAD EDITOR HEAD OF DESIGN & HEAD WEB EDITOR Lilian Diep LAYOUT Nadya Dee-Anne Forbes Ashley Hirasuna ASSITANT HEAD EDITOR ASSITANT WEB EDITOR Lauren Hill COVER PHOTO Amy Brown Shantel Dickerson SECTION EDITORS SOCIAL MEDIA Kirsty Broderick TABLE OF CONTENTS John Wilson Jack Richardson Michelle Cerami Shantel Dickerson PHOTO Hayley Closter Shantel Dickerson Nicole Antkiewicz COPY EDITORS Verushka Aucamp Jasmin Hayward ART & PHOTOGRAPHY Tresha Barrett Tresha Barrett Hannah Varacalli Bailey Jo Josie Jasmin Hayward Abby Ryder-Huth Hannah Martin Sabrina Zirakzadeh Shantel Dickerson Jocelyn Russell Illaura Rossiter Micah Briguera Ashley Hirasuna This magazine contains original photos used with permission, as well as free-use images. All included photos are property of the author unless otherwise specified. If you are the owner of an image featured in this publication believed to be used without permission, please contact the Head of Graphic Design and Layout, Ashley Hirasuna, at ashley. [email protected]. This edition, and all past editions of AJET CONNECT, -

Habitual Difference in Fashion Behavior of Female College Students Between Japan and Thailand

Advances in Applied Sociology 2012. Vol.2, No.4, 260-267 Published Online December 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2012.24034 Habitual Difference in Fashion Behavior of Female College Students between Japan and Thailand Aliyaapon Jiratanatiteenun1, Chiyomi Mizutani2, Saori Kitaguchi3, Tetsuya Sato3, Kanji Kajiwara4 1Department of Engineering Design, Kyoto Institute of Technology, Kyoto, Japan 2Department of Textile and Clothing, Otsuma Women’s University, Tokyo, Japan 3The Center for Fiber and Textile Science, Kyoto Institute of Technology, Kyoto, Japan 4Fibre Innovation Incubator, Shinshu University, Nagano, Japan Email: [email protected] Received September 28th, 2012; revised October 30th, 2012; accepted November 13th, 2012 The purpose of this study is to elucidate a role of the street fashion as a habitual communication tool for the youth through the comparative study on the habitual behavior of the Japanese and Thai youths. The questionnaires concerning the fashion behavior were submitted to a total of 363 female college students in Japan and Thailand in 2011. The results revealed the significant differences in fashion behavior between the two countries, which were affected by the climate, personal income, and traditional lifestyle. The Japanese youths care much about their personal surroundings and adapt fashion as a communication tool for social networking to be accepted in a group. The Thai youths care less about fashion and seek for other tools for social networking. By the time of the survey, the Japanese street fashion has been already matured as a communication tool with a variety of expression ways and is transfiguring spontaneously by repeated diversification and integration of several fashion elements. -

Evolution of Male Self-Expression. the Socio-Economic Phenomenon As Seen in Japanese Men’S Fashion Magazines

www.ees.uni.opole.pl ISSN paper version 1642-2597 ISSN electronic version 2081-8319 Economic and Environmental Studies Vol. 18, No 1 (45/2018), 211-248, March 2018 Evolution of male self-expression. The socio-economic phenomenon as seen in Japanese men’s fashion magazines Mariusz KOSTRZEWSKI1, Wojciech NOWAK2 1 Warsaw University of Technology, Poland 2 Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland Abstract: Visual aesthetics represented in Western media by the name of “Japanese style”, is presented from the point of view of women’s fashion, especially in the realm of pop-culture. The resources available for non- Japanese reader rarely raise the subject of Japanese men’s fashion in the context of giving voice to self- expression by means of style and clothing. The aim of this paper is to supplement the information on the socio- economic correlation between the Japanese economy, fashion market, and self-expression of Japanese men, including their views on masculinity and gender, based on the profile of Japanese men’s fashion magazines readers. The paper presents six different fashion styles indigenous to metropolitan Japan, their characteristics, background and development, emphasizing the connections to certain lifestyle and socio-economic occurrences, resulting in an emergence of a new pattern in masculinity – the herbivorous man, whose requirements and needs are analyzed considering his status in the consumer market and society. Keywords: salaryman, kireime kei, salon mode kei, ojii boy kei, gyaru-o kei, street mode kei, mode kei, sōshokukei danshi, sōshoku danshi, Non-no boy, Popeye boy, the city boy, Japan, fashion, consumer market JEL codes: H89, I31, J17, Z00 https://doi.org/10.25167/ees.2018.45.13 Correspondence Address: Mariusz Kostrzewski, Faculty of Transport, Warsaw University of Technology, Koszykowa 75, 00-662 Warszawa, Poland. -

Fashion Talks… Back Issues As of November 9, 2020 *For Actual Stock, Please Refer to “List of Our Current Stock”

Fashion Talks… Back Issues As of November 9, 2020 *For actual stock, please refer to “List of our current stock”. Fashion Talks... SPRING 2015 / VOL. 1[underwear] ■Pleasure and Anxiety over a Piece of Cloth by Naoyuki KINOSHITA ■Reception of Western-style Underwear in the Taisho and Early Showa Period by Mihoko AOKI ■Eyes over Underwear in the Western History by Shigeru KASHIMA ■Fashion through the KCI Collection: Underwear from 18th Century to 1920s ■Virility, Enhancement and Men's Underwear by Shaun COLE ■NEW ACQUISITIONS [EXHIBITION REVIEWS] □Wardrobe Momories by Mizuki TSUJI □Hippie Chic / Dufy / Bishojo: Young Pretty Girls in Art History / Ages of Sarasa / Spirit of Life in the North of Japan □World of Corset at the KCI Gallery Fashion Talks... AUTUMN 2015 / VOL. 2[underwear 2] ■Public Underwear and Private Underwear by Yoshiko TOKUI ■About so-called Chirarism by Syoichi INOUE ■Pass by man and woman and panty by Chizuko UENO ■Fashion through the KCI Collection 2 ■NEW ACQUISITIONS ■Craze and Shame: Rubber Clothing during the Nineteenth Century in Paris, London, and New York City by Manuel CHARPY [EXHIBITION REVIEWS] Jeanne Lanvin/Déboutonner la mode Fashion Talks... SPRING 2016 / VOL. 3[economy 1] ■An establishment process and the present of the department store in Europe by Seiichi KITAYAMA ■The fashion industry prehistory of mode city Paris by Nao TSUNODA ■Fashion through the KCI Collection 3 ■The modernization of consumption and The Initial department store in Japan by Yuki JINNO ■The formation of the apparel industry in Japan by Akihiro KINOSHITA ■NEW ACQUISITIONS [EXHIBITION REVIEWS] Jean Paul Gaultier/Dries Van Noten. -

GAY JAPAN a Manaboutworld Insider Guide JAPAN: EVERYTHING IS an ADVENTURE

GAY JAPAN A ManAboutWorld Insider Guide JAPAN: EVERYTHING IS AN ADVENTURE o best understand Japan, you should fly there on a Japanese airline. The pleasantness is stunning, and while you first notice it in the professional and gracious crew, it is not because of them. It is because of the high ratio of Japanese pas- sengers. An ancient culture of conformity, respect and ritual has begotten a modern culture of people who are unusually respectful, orderly and polite. There’s even an animated in flight video on JAL, demonstrating good flight etiquette, in- Tcluding things we’ve never done, like alerting the passenger behind you before reclining your seat. It sure makes for a pleasant cabin (as did the extra humidity and oxygen of the air on our 787 Dreamliner — that’s another story). But these same cultural forces are the ones that stunt the liberation of the Japanese LGBT community. They are at the heart of every internal Japanese conflict, an amplified expression of the conflict we all experience between holding on to the past, and growing into the future. It shouldn’t seem so foreign to us. But it does. And that’s the heart of any Japanese adventure. From its earliest interactions with Dutch and Portuguese traders, Japan has kept foreigners at a distance. And yet its rituals of hospitality are unrivaled in their intricacy and graciousness. For western travelers, a visit to Japan opens windows to both the past and the future. This is easily visible in the juxtaposition of tourist staples like tea ceremonies and bullet trains. -

Tokyo Pocket Guide Harajuku Map Attractions Tokyo Pocket Guide Harajuku Map English

TOKYO POCKET GUIDE HARAJUKU MAP ATTRACTIONS Gim Togo AO Hipanda TOGO Tiger A B Nubian C D E F G H I 1 SHRINEShrine HUG Conv Aeropostal Shinjuku Stay Hassayadai Real Mojo 2030 Regatte Bring Toilet Whoop-de-doo Not Conventional Warp RamidusAbstract Takenoko RichardsGorakudo StylelandiaWorld What’s Tokia Happy Hearts Body Line Xing Fu Connection Blue TAKESHITA-DORIBroadway St #00TD Redeye Cosmura Gold’s Blackanny With Box Up 3/4 7/11 AC/DC Innisfree Gym Stormy Marion Romantic 1 Jean’sMate Wego Atmos gettry Standard asics MoMon Brand Tourist My Pouch Claire’s kuro Collect Info Wendy’s TAKESHITA-DORI STREET Murasaki Loyd Daiso Burlesque CalienteNadia Paris Kids WC MAP StrawGFC A.P.C. 2 Ruo Candy-a-gogoCute Cube McD’s Calbee Etudeto Alice Brand Wego Bic Matsumoto TokiaYosukeKokumin Me Santa LotteriaCollect Blowz Monica Etude New DisneyAlta Studious 2 Studious Conv Tutu Anna Balance GoodCalzedonia Day 2nd Takeshita-doriCS T&PSilhouette Street Anap A’gem Street Rinkan Girl Stussy Takeshita TabioDor Panama DNA Royal Yoshinoya Noa Boy Moosh Closet Child Tea SB's Surku studious Sunny B-side exit Champion AC/DC Anap Advan Studious 3 Bazz Bopper Le Rag Shining Attractions Carhartt Fonte Fake Store Diana P-mimi Abettor 2 Farms HUF Noah Viva Extreme X-Large Kamo Acryl Rawdrip Bones Goa Undefeated Aape Junk Yard Supreme flamingo X-girl Skechers Avex Reversal Artists LHP Neighbor 3 Alley Galaxy LaDonna Candy Bubbles Pool Stripper Undefeated Polcadot Tha Terminal Oshman’s Prisila 3 H&M Line Friends Luigi Billy’s U Deeta Leflah Beauty Square Fools Punk Chicago -

Modern Japanese Fashion

Loretta Gray Social Studies/English Language Arts Grades 6, 7, 8 Section 5: Modern Japanese Fashion Purpose: Students will be introduced to traditional and contemporary Japanese fashion; and explore Japan and Japanese street fashion to become aware of popular examples of Japanese street fashion trends. There will be discussions on contemporary Japanese fashion and its meaning to the younger generation in Japan (e.g. cosplay, youth culture and high fashion culture). Students will be able to: Identify/ locate/color/label Japan on a world map/globe Describe clothing/garments Draw street fashion garments Write descriptive summaries Create fashion scrapbooks Duration: Two 40 minute class periods (Two-day focus) Materials: World Map or Globe (teacher) Map of Japan (students) Japan and Japanese Street Fashion KWL graphic organizer (attached) Colored pencils Pencils Notebook paper Double pocket 3-ring folders Glue Scissors White paper Computer w/Internet access Essential Questions (Two-Day Focus) What do you know about Japan? What do you want to know? What have you learned? What continent is Japan located on? Where is Japan? What types of clothes are popular? Who wears the styles? Introduction to the History/Culture of Japan: Japanese Fashion When talking about fashion in Japan it is just impossible not to acknowledge the fact that the Japanese have an incredible sense of style. Fashion plays a huge role in the lives of the Japanese because they have a special outlook towards clothing. In Japan, fashion is considered as a way to express yourself, set your own style, and show others that you are aware of the newest trends. -

Shibuya Festival 2019 Date and Time:November 2 (Sat.) and 3 (Sun., Holiday)

The number for the Shibuya City Office is 3463-1211. If possible, tell the switchboard operator the extension for the section you wish to speak to. If you wish to make your inquiries in English, please contact the Intercultural Exchange Promotion Section, Cultural Promotion Division( Tel: 3463-1142). Editor: Shibuya City Office, Planning Department, Public Relations and Communications Division. Address: 1-1 Udagawa, Shibuya-ku Tel: 3463- 1287 HP: https://www.city.shibuya.tokyo.jp/ 42nd Hometown Shibuya Festival 2019 Date and time:November 2 (Sat.) and 3 (Sun., holiday) From 10:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. on the 2nd and to 4:00 p.m. on the 3rd the festival will be held even if it Venues:Section B of Yoyogi Park, other rains The Hometown Shibuya Festival is an occasion ★ for municipal residents to gather together and Directions to Venues ( ) Meiji Jingu Yoyogi Park relax, when people who love Shibuya join hands Shrine Harajuku Sta. Hachiko Bus in an effort to create a Shibuya that will make Yoyogi Koen stop Omotesando NHK Yoyogi National Stadium us all proud. The festival has three themes (under renovation) Meiji-dori St. Shibuya City Office Hachiko Bus Shibuya Kuyakusho stop “Shibuya—Turning Differences into Strengths,” Shibuya City Office temporary building “Hometown Shibuya—International and Peaceful Koen-dori St. Workers’ Welfare Hall City” and “I move. Shibuya changes.” All three Koen-dori St. JR are meant to convey the joy of living happily and helping each other. This year’s festival will be Access Miyamasu-zaka St. Ten-minute walk from Shibuya Station Shibuya Sta. -

Breaking the Rules of Kimono a New Book Shatters Antiquated Views of This Traditional Garment

JULY 2017 Japan’s number one English language magazine BREAKING THE RULES OF KIMONO A NEW BOOK SHATTERS ANTIQUATED VIEWS OF THIS TRADITIONAL GARMENT PLUS: The Boys for Sale in Shinjuku, Best Sake of 2017, Japan's New Emperor, and What Really Goes on Inside "Terrace House" To all investors and customers of e Parkhouse series: e Mitsubishi Jisho Residence overseas sales team is on hand for all your needs For the most up-to-date information about Mitsubishi Jisho Residence's new real estate projects, please visit our English website at www.mecsumai.com/international/en For inquiries, please email [email protected] Live in a Home for Life. e Parkhouse 34 26 32 36 JULY 2017 radar in-depth 36 BOYS FOR SALE THIS MONTH’S HEAD TURNERS COFFEE-BREAK READS A new documentary brings to light a particu- lar kind of sex trade in Shinjuku Ni-chome. 8 AREA GUIDE: YURAKUCHO 26 BREAKING THE RULES OF KIMONO This old-school neighborhood has a few A new book shows off the different person- modern surprises up its sleeve. alities of this very traditional garment. guide 14 STYLE 30 THE LIFE AND LOVE OF JAPAN'S CULTURE ROUNDUP Ready for a summer romance? Get your NEW EMPEROR 40 ART & FICTION spark back with some flirtatious swimwear As Emperor Akihito prepares to step down, Julian Lennon shows off his photography, all eyes are turning towards his son. and a new spy novel wends its way into 18 BEAUTY North Korea. Shake up your make-up with a full kit of 32 THE MISUNDERSTOOD CROWS organic, natural cosmetics.