The Great Divorce by C.S. Lewis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

<I>Screwtape Letters</I> and <I>The Great Divorce

Volume 17 Number 1 Article 7 Fall 10-15-1990 Immortal Horrors and Everlasting Splendours: C.S. Lewis' Screwtape Letters and The Great Divorce Douglas Loney Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Loney, Douglas (1990) "Immortal Horrors and Everlasting Splendours: C.S. Lewis' Screwtape Letters and The Great Divorce," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 17 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol17/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Sees Screwtape and The Great Divorce as constituting “something like a sub-genre within the Lewis canon.” Both have explicit religious intention, were written during WWII, and use a “rather informal, episodic structure.” Analyzes the different perspectives of each work, and their treatment of the themes of Body and Spirit, Time and Eternity, and Love. -

Interventions for Children Experiencing Complex Trauma (Developmental Trauma Disorder)

1 Interventions for Children Experiencing Complex Trauma (Developmental Trauma Disorder) Preliminary Compilation from Research Project, Classroom Support for Children with Complex Trauma and Attachment Disruption Linda O’Neill, Andrew Kitchenham, and Tina Fraser, UNBC Serena George, Research Associate Joanna Pooley, Research Assistant Sarah Henklemen, Research Assistant Funded through SSHRC Partnership Development Grant 2 Introduction In our work to better understand and support children who have experienced Type I trauma (single-event, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) and Type II trauma (multiple events of an interpersonal nature, complex trauma also named developmental trauma disorder [DTD]) and the caregivers, teachers, counsellors and support staff who help these children, our team has worked to compile interventions and approaches that are designed by to establish safety for such children and aid in lowering distress. The following interventions and strategies were designed by researchers and experienced practitioners and come from various sources that are fully referenced in the appendix. Caregivers, teachers, counsellors and other helpers are strongly recommended to have a basic understanding of trauma-informed practice before using the following interventions. In all trauma support work, safety is paramount. A safe environment is critical for children with complex trauma reactions, with the establishment of safety the first stage of all trauma work (Aideuis, 2007; Courtois, 2008; Herman, 1997). For children who now see the world in a negative light and do not trust others, interventions can only succeed in a safe environment where self-efficacy and a sense of mastery are fostered (Faust & Katchen, 2004). The Attachment, Self-regulation and Competency (ARC) strengths-based model developed by Kinniburgh and Blaustein (2005) is a components based framework informed by attachment and traumatic stress theories. -

Myth in CS Lewis's Perelandra

Walls 1 A Hierarchy of Love: Myth in C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Communication In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English by Joseph Robert Walls May 2012 Walls 2 Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in English _______________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Dr. Branson Woodard, D.A. _______________________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Dr. Carl Curtis, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Dr. Mary Elizabeth Davis, Ph.D. Walls 3 For Alyson Your continual encouragement, support, and empathy are invaluable to me. Walls 4 Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: Understanding Symbol, Myth, and Allegory in Perelandra........................................11 Chapter 2: Myth and Sacramentalism Through Character ............................................................32 Chapter 3: On Depictions of Evil...................................................................................................59 Chapter 4: Mythical Interaction with Landscape...........................................................................74 A Conclusion Transposed..............................................................................................................91 Works Cited ...................................................................................................................................94 -

Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator

Volume 22 Number 2 Article 3 1998 Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator Diana Pavlac Glyer Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Glyer, Diana Pavlac (1998) "Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Biography of Joy Davidman Lewis and her influence on C.S. Lewis. Additional Keywords Davidman, Joy—Biography; Davidman, Joy—Criticism and interpretation; Davidman, Joy—Influence on C.S. Lewis; Davidman, Joy—Religion; Davidman, Joy. Smoke on the Mountain; Lewis, C.S.—Influence of Joy Davidman (Lewis); Lewis, C.S. -

2014 COMMUNITY SURVEY an Assessment by Citizens of Richland’S Strategic Leadership Plan

2014 COMMUNITY SURVEY An assessment by citizens of Richland’s Strategic Leadership Plan. CITY OF RICHLAND 2014 COMMUNITY SURVEY RESULTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report provides an executive summary of the results of Richland’s 2014 Community Survey. The Communications and Marketing Office administered the municipal survey during late 2014. In 2011, a baseline survey was created for the primary purpose of asking residents to assess their level of satisfaction with City Council-identified benchmarks and to obtain input toward potential goals for the Strategic Leadership Plan (SLP). The City conducted the survey in late 2014 so that City Council would receive an analysis of the results prior to its 2015 planning retreat. This timing will allow council to consider residents’ satisfaction levels with current services, suggestions, and comments in establishing the next set of five-year goals for the SLP. This, in turn, will guide the municipal staff in, first, identifying objectives to reach the goals and, second, recommending a budget for future years that will accomplish those objectives. ADMINISTERED BY THE CITY OF RICHLAND, WASHINGTON Communications & Marketing office | 2014 SURVEY METHODOLOGY The City conducted its 2014 survey through a web-based service. The City mailed postcards to a sampling of 4,250 residents, selected at random from the City’s utility customer base, inviting them to participate in the survey and instructing them how to access the survey via the City’s website. The postcard invited recipients without internet access and those who preferred a paper survey to request one by phoning the Communications and Marketing Office. Fifty-five residents requested paper copies of the survey; 45 of those completed and returned their surveys. -

C.S. Lewis' <I>The Great Divorce</I> and the Medieval Dream Vision

Volume 10 Number 2 Article 12 1983 C.S. Lewis' The Great Divorce and the Medieval Dream Vision Robert Boeing Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Boeing, Robert (1983) "C.S. Lewis' The Great Divorce and the Medieval Dream Vision," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 10 : No. 2 , Article 12. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol10/iss2/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Discusses the genre of the medieval dream vision, with summaries of some of the best known (and their precursors). Analyzes The Great Divorce as “a Medieval Dream Vision in which [Lewis] redirects the concerns of the entire genre.” Additional Keywords Lewis, C.S. -

The Immanence of Heaven in the Fiction of CS Lewis and George

Shadows that Fall: The Immanence of Heaven in the Fiction of C. S. Lewis and George MacDonald David Manley Our life is no dream; but it ought to become one, and perhaps will. (Novalis) Solids whose shadow lay Across time, here (All subterfuge dispelled) Show hard and clear. (C.S. Lewis, “Emendation for the End of Goethe’s Faust”) .S. Lewis’s impressions of heaven, including the distinctive notions ofC Shadow-lands and Sehnsucht, were shaped by George MacDonald’s fiction.1 The vision of heaven Lewis and MacDonald share is central to their stories because it constitutes the telos of their main characters; for example, the quest for heaven is fundamental to both Lewis’s The Pilgrim’s Regress and MacDonald’s “The Golden Key.” Throughout their fiction, both writers reveal a world haunted by heaven and both relate rapturous human longing after the source of earthly glimpses; both show that the highest function of art is to initiate these visions of heaven; and both describe a heaven that swallows up Earth in an all-embracing finality. The play Shadowlands is aptly named; for Lewis, the greatest earthly joys were merely intimations of another world where beauty, in Hopkins’s words, is “kept / Far with fonder a care” (“The Golden Echo” lines 44-45). He was repeatedly “surprised by Joy,” overcome with flashes ofSehnsucht during which he felt he had “tasted Heaven” (Surprised 135). For Lewis, “. heaven remembering throws / Sweet influence still on earth . .” (“The Naked Seed” 19-20). This “sweet influence” is a desire, not satisfaction; in his words, it is a “hunger better than any other fullness” (“Preface” from Pilgrim 7). -

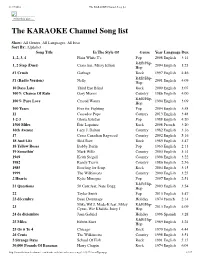

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

'The Full Treatment': C. S. Lewis on Repentance, the Process Of

The Dulia et Latria Journal, Vol. 3 (2010) 21 The “Full Treatment”: C. S. Lewis on Repentance, the Process of Becoming a “New-Made Man” By Chris Garrett Oklahoma City University (documentation in author’s style) The ultimate spiritual goal of most Christians is to go to heaven and live with God after death. According the Christian apologist C. S. Lewis, God desires to prepare us for eternal life by making us into new creatures. Having set the standard of absolute perfection before us and knowing that humanity falls short of that standard, God has prepared a way for man to become perfected. Through the atonement of Jesus Christ and the process of repentance man can be forgiven of sins and become glorified, immortal creatures. This essay explores and examines Lewis’s ideas on this core Christian principle of repentance. Lewis defines repentance as a gradual process of transformation that will not be completed during mortality (Mere Christianity 159-161). It is a process of surrender, in essence killing a part of yourself (44-45). By that Lewis is referring to his belief that man is an amphibian—“half animal and half spirit” (Screwtape Letters 36). When man surrenders to God, he attempts to forsake the natural and carnal man (the animal part) in favor of following his spiritual self. 22 Chris Garrett, “Lewis on Repentance” An important aspect of repentance is realizing you are on the wrong track and then getting back on the right road (Mere Christianity 44). Lewis describes repentance in terms of progress: We all want progress. -

Grimoire 1980

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Grimoire University Publications 1980 Grimoire 1980 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/grimoire Recommended Citation La Salle University, "Grimoire 1980" (1980). Grimoire. 61. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/grimoire/61 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grimoire by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. g r im o ir e g rim o ire La Salle College Student Arts Publication Managing Editor Lisa NelsonNelson A r t - Photography Editors Kathy Boyd John Di Donato Christopher A. Lucca James Palumbo Linda Barber Angela Martella Florence D’Ambrosio Cathy Moser Donna Feiler Mary O’Brien Renee Fairconcture Peter Speaker Paula Krebs Veronica Syndor Joe Lew Gregory Schmitt Beverly Martin Daniel Walker Business Consultant Richard Lautz Christine Lysionek C o v e r Robert Sicoramsa CONTENTS Page Approaching Distances........... 3 ............John Di Donato Photo.......................................... 3 ...................Louis Mosca Arriving at Departure.............. 4 ............John Di Donato Past the Cardboard Valley.. 5 ................ Daniel Walker The Snow Queens..................... 5 ................ Neil Silverman Illustration................................ 6 . Enrico D. Gamalinda Liberty, some farce.................. -

Dante's Divine Comedy in the Novels of CS Lewis

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of English Department of English 6-2016 Reflecting the Eternal: Dante's Divine Comedy in the Novels of C. S. Lewis (Book Review) Gary L. Tandy George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/eng_fac Part of the Christianity Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Tandy, Gary L., "Reflecting the Eternal: Dante's Divine Comedy in the Novels of C. S. Lewis (Book Review)" (2016). Faculty Publications - Department of English. 57. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/eng_fac/57 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of English by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reflecting the Eternal: Dante’s Divine Comedy in the Novels of c. 5. Lewis■ By Marsha Daigle-Williamson, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2015. ISBN 978-1- 61970-665-1. Pp. 330. $16.95. That c. s. lewis was a great admirer of Dante’s poetry, specifically his Divine Comedy, will come as no surprise to readers of Lewis’s fiction, literary criticism, and letters. At his first reading of the poem as a 20-year-old, Lewis stated that the Paradiso reaches ”heights of poetry you get nowhere else” (Letter to Arthur Greeves, October 13, 1918), and 10 years later he thought ”Dante’s poetry, on the whole, the greatest of all the poetry” he had read (Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature, 76). -

The Great Divorce: C.S. Lewis – Falling Between the Cracks

Douglas Ayling THEO 656A: Augustine: City of God The Great Divorce: C.S. Lewis – Falling between the cracks Unless otherwise stated, all page numbers refer to: C.S. Lewis, The Great Divorce (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1946) The structure of this paper will be as follows. First a brief synopsis of the plot of The Great Divorce is provided. I then delineate aspects of the theological position which Clive Staples “Jack” Lewis appears to stake out in this work of fiction. Discussion follows of the implications, some possible difficulties and internal inconsistencies. Then, in the context of Saint Augustine of Hippo’s City of God, I do my best to get the texts talking to each other. Again, the caveat: my competence to implement the above is limited. I entreat your patience where necessary. 1. Plot synopsis: The Great Divorce In this relatively short allegorical novel, C.S. Lewis’ first person narrator journeys by bus upwards from a dreary suburban purgatory / hell to another realm where above and beyond a pastoral idyll, an alpine divine resides. We see, first on the bus, later in heaven, a series of undesirable characters. Their faults are usually obvious and serve to provide illustrations of why they will get back onto the bus and go back to purgatory / hell. The welcoming party consists of nominated counterparts who have interrupted their journey “further and further into the mountains” (p.69). In most of these cases they knew the arrival while they were alive and the pilgrim is required to walk with them, receiving assistance on the journey towards God.