Anti-Slavery Movement, Britain Jason M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Treaties: a Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. University of Southampton Department of History After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History June 2018 i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam This study is built on an investigation of a large number of archival sources, but in particular the Journals and Votes of the House of the Assembly of Jamaica, drawn from resources in Britain and Jamaica. Using data drawn from these primary sources, I assess how the Maroons of Jamaica forged an identity for themselves in the century under slavery following the peace treaties of 1739 and 1740. -

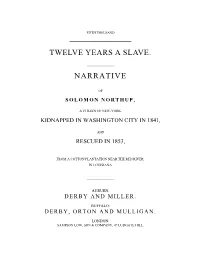

Twelve Years a Slave. Narrative

FIFTH THOUSAND TWELVE YEARS A SLAVE. NARRATIVE OF SOLOMON NORTHUP, A CITIZEN OF NEW-YORK, KIDNAPPED IN WASHINGTON CITY IN 1841, AND RESCUED IN 1853, FROM A COTTON PLANTATION NEAR THE RED RIVER, IN LOUISIANA. AUBURN: DERBY AND MILLER. BUFFALO: DERBY, ORTON AND MULLIGAN. LONDON: SAMPSON LOW, SON & COMPANY, 47 LUDGATE HILL. 1853. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-three, by D E R B Y A N D M ILLER , In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Northern District of New-York. ENTERED IN LONDON AT STATIONERS' HALL. TO HARRIET BEECHER STOWE: WHOSE NAME, THROUGHOUT THE WORLD, IS IDENTIFIED WITH THE GREAT REFORM: THIS NARRATIVE, AFFORDING ANOTHER Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED "Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone To reverence what is ancient, and can plead A course of long observance for its use, That even servitude, the worst of ills, Because delivered down from sire to son, Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing. But is it fit, or can it bear the shock Of rational discussion, that a man Compounded and made up, like other men, Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust And folly in as ample measure meet, As in the bosom of the slave he rules, Should be a despot absolute, and boast Himself the only freeman of his land?" Cowper. [Pg vii] CONTENTS. PAGE. EDITOR'S PREFACE, 15 CHAPTER I. Introductory—Ancestry—The Northup Family—Birth and Parentage—Mintus Northup—Marriage with Anne Hampton—Good Resolutions—Champlain Canal—Rafting Excursion to Canada— Farming—The Violin—Cooking—Removal to Saratoga—Parker and Perry—Slaves and Slavery— The Children—The Beginning of Sorrow, 17 CHAPTER II. -

Recession of 1797?

SAE./No.48/February 2016 Studies in Applied Economics WHAT CAUSED THE RECESSION OF 1797? Nicholas A. Curott and Tyler A. Watts Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise What Caused the Recession of 1797? By Nicholas A. Curott and Tyler A. Watts Copyright 2015 by Nicholas A. Curott and Tyler A. Watts About the Series The Studies in Applied Economics series is under the general direction of Prof. Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise ([email protected]). About the Authors Nicholas A. Curott ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of Economics at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana. Tyler A. Watts is Professor of Economics at East Texas Baptist University in Marshall, Texas. Abstract This paper presents a monetary explanation for the U.S. recession of 1797. Credit expansion initiated by the Bank of the United States in the early 1790s unleashed a bout of inflation and low real interest rates, which spurred a speculative investment bubble in real estate and capital intensive manufacturing and infrastructure projects. A correction occurred as domestic inflation created a disparity in international prices that led to a reduction in net exports. Specie flowed out of the country, prices began to fall, and real interest rates spiked. In the ensuing credit crunch, businesses reliant upon rolling over short term debt were rendered unsustainable. The general economic downturn, which ensued throughout 1797 and 1798, involved declines in the price level and nominal GDP, the bursting of the real estate bubble, and a cluster of personal bankruptcies and business failures. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

1 1. Suppression of the Atlantic Slave Trade

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Leeds Beckett Repository 1. Suppression of the Atlantic slave trade: Abolition from ship to shore Robert Burroughs This study provides fresh perspectives on criticalaspects of the British Royal Navy’s suppression of the Atlantic slave trade. It is divided into three sections. The first, Policies, presents a new interpretation of the political framework underwhich slave-trade suppression was executed. Section II, Practices, examines details of the work of the navy’s West African Squadronwhich have been passed over in earlier narrativeaccounts. Section III, Representations, provides the first sustained discussion of the squadron’s wider, cultural significance, and its role in the shaping of geographical knowledge of West Africa.One of our objectives in looking across these three areas—a view from shore to ship and back again--is to understand better how they overlap. Our authors study the interconnections between political and legal decision-making, practical implementation, and cultural production and reception in an anti-slavery pursuit undertaken far from the metropolitan centres in which it was first conceived.Such an approachpromises new insights into what the anti-slave-trade patrols meant to Britain and what the campaign of ‘liberation’ meant for those enslaved Africans andnavalpersonnel, including black sailors, whose lives were most closely entangled in it. The following chapters reassess the policies, practices, and representations of slave- trade suppression by building upon developments in research in political, legal and humanitarian history, naval, imperial and maritime history, medical history, race relations and migration, abolitionist literature and art, nineteenth-century geography, nautical literature and art, and representations of Africa. -

Slave Trade a Select Bibliography

SLAVE TRADE A SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY In Commemoration of the 200thAnniversary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Compiled by Nicole Bryan Genevieve Jones Jessica Lewis Princena Miller Bernadette Worrell National Library of Jamaica 2007 ii Copyright © 2007 by National Library of Jamaica 12 East Street Kingston All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the National Library of Jamaica. Images on Cover (left to right) 1. Slave Auction (J. Blake, Photographer) 2. Group of Negroes as Imported to be Sold as Slaves 3. Sold Into Slavery 4. Negroes Captives Being Forced on Slave Boat Slave trade : a selected bibliography / compiled by the National Library of Jamaica. p. ; cm. In commemoration of the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade ISBN 978-976-8020-04-8 (pbk) 1. Slave trade - Bibliography. 2. Slavery - Bibliography I. National Library of Jamaica 016.306362 dc 22 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................2 Chronology of the Slave Trade ...........................................................4 Reference Notes .................................................................................8 Books and Pamphlets .........................................................................9 Periodical Articles..............................................................................44 Newspaper References.....................................................................47 Manuscripts.......................................................................................53 -

Can Words Lead to War?

Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Full-page illustration from first edition Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Hammatt Billings. Available in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture. Supporting Questions 1. How did Harriet Beecher Stowe describe slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 2. What led Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 3. How did northerners and southerners react to Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 4. How did Uncle Tom’s Cabin affect abolitionism? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Framework for Summary Objective 12: Students will understand the growth of the abolitionist movement in the Teaching American 1830s and the Southern view of the movement as a physical, economic and political threat. Slavery Consider the power of words and examine a video of students using words to try to bring about Staging the Question positive change. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 How did Harriet Beecher What led Harriet Beecher How did people in the How did Uncle Tom’s Stowe describe slavery in Stowe to write Uncle North and South react to Cabin affect abolitionism? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Tom’s Cabin? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Complete a source analysis List four quotes from the Make a T-chart comparing Participate in a structured chart to write a summary sources that point to the viewpoints expressed discussion regarding the of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that Stowe’s motivation and in northern and southern impact Uncle Tom’s Cabin includes main ideas and write a paragraph newspaper reviews of had on abolitionism. -

The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica

timeline The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica Questions A visual exploration of the background to, and events of, this key rebellion by former • What were the causes of the Morant Bay Rebellion? slaves against a colonial authority • How was the rebellion suppressed? • Was it a riot or a rebellion? • What were the consequences of the Morant Bay Rebellion? Attack on the courthouse during the rebellion The initial attack Response from the Jamaican authorities Background to the rebellion Key figures On 11 October 1865, several hundred black people The response of the Jamaican authorities was swift and brutal. Making Like many Jamaicans, both Bogle and Gordon were deeply disappointed about Paul Bogle marched into the town of Morant Bay, the capital of use of the army, Jamaican forces and the Maroons (formerly a community developments since the end of slavery. Although free, Jamaicans were bitter about ■ Leader of the rebellion the mainly sugar-growing parish of St Thomas in the of runaway slaves who were now an irregular but effective army of the the continued political, social and economic domination of the whites. There were ■ A native Baptist preacher East, Jamaica. They pillaged the police station of its colony), the government forcefully put down the rebellion. In the process, also specific problems facing the people: the low wages on the plantations, the ■ Organised the secret meetings weapons and then confronted the volunteer militia nearly 500 people were killed and hundreds of others seriously wounded. lack of access to land for the freed people and the lack of justice in the courts. -

Empire Under Strain 1770-1775

The Empire Under Strain, Part II by Alan Brinkley This reading is excerpted from Chapter Four of Brinkley’s American History: A Survey (12th ed.). I wrote the footnotes. If you use the questions below to guide your note taking (which is a good idea), please be aware that several of the questions have multiple answers. Study Questions 1. How did changing ideas about the nature of government encourage some Americans to support changing the relationship between Britain and the 13 colonies? 2. Why did Americans insist on “no taxation without representation,” and why did Britain’s leaders find this request laughable? 3. After a quiet period, the Tea Act caused tensions between Americans and Britain to rise again. Why? 4. How did Americans resist the Tea Act, and why was this resistance important? (And there is more to this answer than just the tea party.) 5. What were the “Intolerable” Acts, and why did they backfire on Britain? 6. As colonists began to reject British rule, what political institutions took Britain’s place? What did they do? 7. Why was the First Continental Congress significant to the coming of the American Revolution? The Philosophy of Revolt Although a superficial calm settled on the colonies for approximately three years after the Boston Massacre, the crises of the 1760s had helped arouse enduring ideological challenges to England and had produced powerful instruments for publicizing colonial grievances.1 Gradually a political outlook gained a following in America that would ultimately serve to justify revolt. The ideas that would support the Revolution emerged from many sources. -

Leisure Activities in the Colonial Era

PUBLISHED BY THE PAUL REVERE MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION SPRING 2016 ISSUE NO. 122 Leisure Activities in The Colonial Era BY LINDSAY FORECAST daily tasks. “Girls were typically trained in the domestic arts by their mothers. At an early age they might mimic the house- The amount of time devoted to leisure, whether defined as keeping chores of their mothers and older sisters until they recreation, sport, or play, depends on the time available after were permitted to participate actively.” productive work is completed and the value placed on such pursuits at any given moment in time. There is no doubt that from the late 1600s to the mid-1850s, less time was devoted to pure leisure than today. The reasons for this are many – from the length of each day, the time needed for both routine and complex tasks, and religious beliefs about keeping busy with useful work. There is evidence that men, women, and children did pursue leisure activities when they had the chance, but there was just less time available. Toys and descriptions of children’s games survive as does information about card games, dancing, and festivals. Depending on the social standing of the individual and where they lived, what leisure people had was spent in different ways. Activities ranged from the traditional sewing and cooking, to community wide events like house- and barn-raisings. Men had a few more opportunities for what we might call leisure activities but even these were tied closely to home and business. Men in particular might spend time in taverns, where they could catch up on the latest news and, in the 1760s and 1770s, get involved in politics. -

The Writings of Ladies' Abolitionist Societies in Britain, Anna Wood "In Taking a View of the Means Which May Be Employed W

The Writings of Ladies' Abolitionist Societies in Britain, 1825-1833 Anna Wood "In taking a view of the means which may be employed with advantage to effect the mitigation and ultimate extinction of NEGRO SLAVERY, it would be unpardonable to overlook THE LADIES OF THE UNITED KINGDOM, of all classes, and especially of the upper ranks, who have now an opportunity of exerting themselves beneficially in behalf of the most deeply injured of the human race." 1 On April 8, 1825, in the home of Lucy Townsend, the wife of an Anglican clergyman, forty four women gathered to establish the first women's anti-slavery society in Britain. Its initial name was the Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves, but later adopted the name Female Society for Birmingham. This society was committed to the "Amelioration of the Condition of the Unhappy Children of Africa, and especially of Female Negro Slaves."2 This formation preceded that of the first abolition society in the United States, the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, by seven years.3 The Birmingham society actively helped other societies form through various religious network connections. They "acted more like a national than a local society, actively promoting the foundation of local women's societies throughout England, and in Wales and Ireland, 1 Negro Slavery, to the Ladies of the United Kingdom, London, 1 824, Slavery and Anti Slavery, Gale, Wichita State University Libraries (DS 103 7001 86). 2 Clare Midgley, Women Against Slavery: The British Campaigns, 1780-1870 (London: Routledge, 1 992), 43-44. ; Wendy Hamand Venet, Neither Ballots nor Bullets: Women Abolitionists and the Civil War(Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1991 ), 4. -

Loyalists in War, Americans in Peace: the Reintegration of the Loyalists, 1775-1800

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 Aaron N. Coleman University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Coleman, Aaron N., "LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800" (2008). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 620. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/620 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERATION Aaron N. Coleman The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2008 LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 _________________________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _________________________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aaron N. Coleman Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Daniel Blake Smith, Professor of History Lexington, Kentucky 2008 Copyright © Aaron N. Coleman 2008 iv ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION LOYALISTS IN WAR, AMERICANS IN PEACE: THE REINTEGRATION OF THE LOYALISTS, 1775-1800 After the American Revolution a number of Loyalists, those colonial Americans who remained loyal to England during the War for Independence, did not relocate to the other dominions of the British Empire.