What Can We Learn from Rapper and Provocateur, Azealia Banks?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madonna: Reina Del Pop... Y De Los Escándalos

6D EXPRESO Domingo 27 de Abril de 2008 eSTELAR Perez Hilton De a FAN CELEBRIDAD “Trabajo mucho y siempre tengo Gracias a su blog, Perez Hilton se ha acercado nueva información. Además, siempre tengo exclusivas y fui de los primeros en utilizar el formato del blog para in- a las estrellas de Hollywood sin temor y las exhibe formar sobre celebridades. Otra clave es que observo a Hollywood desde el interior y tengo una perspectiva dis- cada vez que puede, pero, ¿él podrá soportar la crítica? tinta”, confiesa. Perez publica exclusivas, incluso antes de que revistas como People lo Salvador Cisneros “Perez Hilton es sólo un persona- hagan. Él fue el primero en hacer pú- publicar que Lance Bass, vocalista de je y la gente no conoce mi verdadera blica la relación de Jessica Simpson y El blog de Perez Hilton se *NSYNC, y Neil Patrick Harris, prota- mado por millones de per- personalidad”, asegura el bloggero vía John Mayer. caracteriza porque en las gonista de Doogie Howser,eranho- sonas que festejan la irre- telefónica desde Los Ángeles. Sin embargo, acepta (a medias) fotografías que publica mosexuales. verencia con la que criti- Y tiene razón. Su voz es calmada que a veces se equivoca porque es hace anotaciones o dibujos “Sé con certeza que algunas ce- Aca a los hollywoodenses y y antes de contestar se toma unos se- humano. que tienden a ridiculizar a lebridades son gays y con otras sólo odiado por centenares de celebrida- gundos para reflexionar las pregun- “Escribí que Fidel Castro falleció los famosos. me gusta bromear al respecto. -

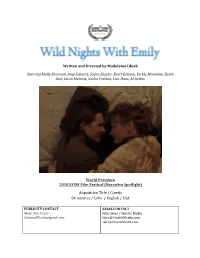

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

Nysba Spring 2020 | Vol

NYSBA SPRING 2020 | VOL. 31 | NO. 2 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association In This Issue n A Case of “Creative Destruction”: Takeaways from the 5Pointz Graffiti Dispute n The American Actress, the English Duchess, and the Privacy Litigation n The Battle Against the Bots: The Legislative Fight Against Ticket Bots ....and more www.nysba.org/EASL NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION In The Arena: A Sports Law Handbook Co-sponsored by the New York State Bar Association and the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section As the world of professional athletics has become more competitive and the issues more complex, so has the need for more reliable representation in the field of sports law. Written by dozens of sports law attorneys and medical professionals, In the Arena: A Sports Law Handbook is a reflection of the multiple issues that face athletes and the attorneys who represent them. Included in this book are chapters on representing professional athletes, NCAA enforcement, advertising, sponsorship, intellectual property rights, doping, concussion-related issues, Title IX and dozens of useful appendices. Table of Contents Intellectual Property Rights and Endorsement Agreements How Trademark Protection Intersects with the Athlete’s EDITORS Right of Publicity Elissa D. Hecker, Esq. Collective Bargaining in the Big Three David Krell, Esq. Agency Law Sports, Torts and Criminal Law PRODUCT INFO AND PRICES 2013 | 539 pages Role of Advertising and Sponsorship in the Business of Sports PN: 4002 (Print) Doping in Sport: A Historical and Current Perspective PN: 4002E (E-Book) Athlete Concussion-Related Issues Non-Members $80 Concussions—From a Neuropsychological and Medical Perspective NYSBA Members $65 In-Arena Giveaways: Sweepstakes Law Basics and Compliance Issues Order multiple titles to take advantage of our low flat Navigating the NCAA Enforcement Process rate shipping charge of $5.95 per order, regardless of the number of items shipped. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK ------X SETH GORDON, Civil Case No

Case 1:20-cv-00696 Document 1 Filed 02/07/20 Page 1 of 9 PageID #: 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK -----------------------------------------------------------------X SETH GORDON, Civil Case No. Plaintiff, COMPLAINT FOR WILLFUL COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT -against- JURY TRIAL DEMANDED BRYTAVIOUS CHAMBERS; DANIEL HERNANDEZ; CREATE MUSIC GROUP, INC.; TENTHOUSAND PROJECTS, LLC; and S.C.U.M GANG INC., Defendants. -----------------------------------------------------------------X Plaintiff, SETH GORDON (“Plaintiff”), by and through undersigned counsel and pursuant to the applicable Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the Local Rules of this Court hereby demands a trial by jury of all claims and issues so triable, and, as for his Complaint against Defendants DANIEL HERNANDEZ; BRYTAVIOUS CHAMBERS; CREATE MUSIC GROUP, INC.; TENTHOUSAND PROJECTS LLC; and S.C.U.M GANG INC. (collectively, “Defendants”) hereby asserts and alleges as follows: NATURE OF ACTION 1. This is a civil action seeking damages and injunctive relief under the Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. § 101 et seq., arising out of Defendants’ extensive unauthorized for-profit use and exploitation of Plaintiff’s original musical composition, registered as the “Yung Gordon Intro” (or the “Drop”), that was created and is wholly owned by the Plaintiff. JURISDICTION AND VENUE 2. Jurisdiction for Plaintiff’s claims lie with the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York pursuant to the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 101 et seq.; 28 U.S.C. § 1331 (conferring original jurisdiction “of all civil actions arising under the Constitution, Case 1:20-cv-00696 Document 1 Filed 02/07/20 Page 2 of 9 PageID #: 2 laws, or treatiEs of the UnitEd StatEs”) and 28 U.S.C. -

Edgewater Discography Download

Edgewater discography download Complete your Edgewater record collection. Discover Edgewater's full discography. Shop new and used Vinyl and CDs. Disponível no Rock Down 13 a discografia completa da banda Edgewater. Não perca tempo e faça logo o seu download. Download Edgewater - Discography () for free. Torrent info - MP3, kbps. Size: MB, Line-up. Micah Creel. Guitar. Jeremy "Worm" Rees. Drums. Justin Middleton. Guitar. Ricky Wolking. Bass. Matt Moseman. Vocals. Albums · Edgewater. Find Edgewater discography, albums and singles on AllMusic. Edgewater discografia completa, todos os álbuns de estúdio, ao vivo, singles e DVDs do artista. Edgewater was a five-piece rock band from the Dallas, Texas area that began in Edgewater would release their self-titled album in July The band began headlining local and regional venues in support of their album, which was. Edgewater discography and songs: Music profile for Edgewater, formed March Genres: Post-Grunge, Alternative Metal. Albums include The Punisher. Some facts about Casino94 Debut Album Download. Sheraton hotel and casino halifax Edgewater casino Casino94 Debut Album Download vancouver poker. Rock is dead? Oh please. Like the ubiquitous toolroach, there's no killing rock -- it will always be around, at least here in the States. And thus, when Edgewater. Music video and lyrics - letras - testo of 'Tres Quatros' by Edgewater. SongsTube List of all songs by Edgewater (A-Z) · Edgewater discography Songstube is against piracy and promotes safe and legal music downloading on Amazon. Music video and lyrics - letras - testo of 'Eyes Wired Shut' by Edgewater. SongsTube List of all songs by Edgewater (A-Z) · Edgewater discography Songstube is against piracy and promotes safe and legal music downloading on Amazon. -

PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + Special Guest Uncle Luke, a Poplife Production, During Miami Art Week in December

PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + Special Guest Uncle Luke, a Poplife Production, during Miami Art Week in December Special one-night-only performance to take place on PAMM’s Terrace Thursday, December 1, 2016 MIAMI – November 9, 2016 – Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) announces PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + special guest Uncle Luke, a Poplife Production, performance in celebration of Miami Art Week this December. Taking over PAMM’s terrace overlooking Biscayne Bay, Norwegian Musician and DJ Cashmere Cat will headline a one-night-only performance, kicking off Art Basel in Miami Beach. The show will also feature projected visual elements, set against the backdrop of the museum’s Herzog & de Meuron-designed building. The evening will continue with sets by Trinidadian DJ and music producer Jillionaire, with a special guest performance by Miami-based Luther “Uncle Luke” Campbell, an icon of Hip Hop who has enjoyed worldwide success while still being true to his Miami roots PAMM Presents Cashmere Cat, Jillionaire + special guest Uncle Luke, takes place on Thursday, December 1, 9pm–midnight, during the museum’s signature Miami Art Week/Art Basel Miami Beach celebration. The event is open to exclusively to PAMM Sustaining and above level members as well as Art Basel Miami Beach, Design Miami/ and Art Miami VIP cardholders. For more information, or to join PAMM as a Sustaining or above level member, visit pamm.org/support or contact 305 375 1709. Cashmere Cat (b. 1987, Norway) is a musical producer and DJ who has risen to fame with 30+ international headline dates including a packed out SXSW, MMW & Music Hall of Williamsburg, and recent single ‘With Me’, which premiered with Zane Lowe on BBC Radio One & video premiere at Rolling Stone. -

At the Jericho Tavern on Saturday NIGHTSHIFT PHOTOGRAPHER 10Th November

[email protected] nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 207 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2012 Alphabet Backwards photo: Jenny Hardcore photo: Jenny Hardcore Go pop! NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net DAMO SUZUKI is set to headline The album is available to download this year’s Audioscope festival. The for a bargain £5 at legendary former Can singer will www.musicforagoodhome.com. play a set with The ODC Drumline at the Jericho Tavern on Saturday NIGHTSHIFT PHOTOGRAPHER 10th November. Damo first headlined Johnny Moto officially launches his Audioscope back in 2003 and has new photo exhibition at the Jericho SUPERGRASS will receive a special Performing Rights Society Heritage made occasional return visits to Tavern with a gig at the same venue Award this month. The band, who formed in 1993, will receive the award Oxford since, including a spectacular this month. at The Jericho Tavern, the legendary venue where they signed their record set at Truck Festival in 2009 backed Johnny has been taking photos of deal back in 1994 before going on to release six studio albums and a string by an all-star cast of Oxfordshire local gigs for over 25 years now, of hit singles, helping to put the Oxford music scene on the world map in the musicians. capturing many of the best local and process. Joining Suzuki at Audioscope, which touring acts to pass through the city Gaz Coombes, Mick Quinn and Danny Goffey will receive the award at the raises money for homeless charity in that time and a remains a familiar Tavern on October 3rd. -

Turns to Affect in Feminist Film Theory 97 Anu Koivunen Sound and Feminist Modernity in Black Women’S Film Narratives 111 Geetha Ramanathan

European Film Studies Mutations and Appropriations in THE KEY DEBATES FEMINISMS Laura Mulvey and 5 Anna Backman Rogers (eds.) Amsterdam University Press Feminisms The Key Debates Mutations and Appropriations in European Film Studies Series Editors Ian Christie, Dominique Chateau, Annie van den Oever Feminisms Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures Edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover design: Neon, design and communications | Sabine Mannel Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 676 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 363 4 doi 10.5117/9789089646767 nur 670 © L. Mulvey, A. Backman Rogers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Editorial 9 Preface 10 Acknowledgments 15 Introduction: 1970s Feminist Film Theory and the Obsolescent Object 17 Laura Mulvey PART I New Perspectives: Images and the Female Body Disconnected Heroines, Icy Intelligence: Reframing Feminism(s) -

Quarterly Magazine

FLORIDA- CARIBBEAN Caribbean Cruising CRUISE THE FLORIDA-CARIBBEAN CRUISE ASSOCIATION MAGAZINE ASSOCIATION Third Quarter 2007 EXECUTIVE FEATURES COMMITTEE FCCAMicky Chairman, Arison Chairman & CEO 9 The 2007 FCCA Caribbean Cruise Conference and Trade Show. Carnival Corporation Join us in Cozumel, Mexico to foster new relationships. PresidentThomas M. McAlpin 12 A Look Inside Playa Mia Grand Beach Park. Disney Cruise Line 18 What Destinations Can Learn From Disney Cruise Line. PresidentRichard &E. CEO Sasso MSC Cruises (USA) Inc. By Tom McAlpin, President - Disney Cruise Line. PresidentColin V eitch& CEO 24 Port Everglades Expands for the Future. Norwegian Cruise Line 28 Tours - Thinking Outside the Box. VStephenice President, A. Nielsen By Darius Mehta, Director Land Programs - Regent Seven Caribbean & Atlantic Shore Operations Seas Cruises. Princess Cruises/Cunard Line 30 Cozumel - An Island of Cultural Treasures. PrAdamesident Goldstein Royal Caribbean International RCCL’s Patrick Schneider, Director of Shore Excursions Shares FCCA STAff 34 RCCL’s Patrick Schneider, Director of Shore Excursions Shares His Goals With Us. GraphicsOmari BrCoordinatoreakenridge 36 Cruise Control - Managing the Cruise Industry. Director,Terri Cannici Special Events By Vincent Vanderpool-Wallace, Secretary General & CEO, Caribbean Tourism Organization. VAdamice President Ceserano 40 NCL Welcomes New Billion Dollar Shareholder to Freestyle ExecutiveJessica LalamaAssistant Cruising and the Industry’s Youngest Fleet. Star Cruises and Apollo Team Up to Boost -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

The Tusker Tribune the Student Newspaper of Somers Middle School

The Tusker Tribune The Student Newspaper of Somers Middle School Issue Number 25 http://somersschools.org/domain/995 Spring 2018 7th Grade Zoo Trip Means Spring’s Here! By Ezra Weinstein it; we turned to see one huge lion that had a Tusker Tribune Staff beautiful mane and a fierce look on its face. Most people know that the sev- The lion was so cool but something was wrong. enth grade is going to be going to the The lion would not stop looking at me. It Bronx Zoo on Friday, April 20 to see stared and stared. I kept glancing at the lion the animals. Sounds like fun, right? and he did not stop staring. I believe it will be an amazing expe- Weinstein’s About five minutes later, he pranced rience for us students. Even though I have Wisdom over to me and put his paw on the glass and only been to the Bronx Zoo once, I can I put my tiny hand on the glass. It covered even tell you it is extremely probably ¼ of his humungous fascinating to watch the ani- paw. A friendship between boy mals in their habitats. and lion had been just awak- At the zoo, there are ened. I heard my mother call to some exotic animals there like me to say that we had to leave; it tigers, lions, and other animals was sad to see the lion look at you do not see every day. That me. He looked lonely as soon as I one time I went to the Bronx took that first step away from Zoo with my family, something him. -

Major Lazer Essential Mix Free Download

Major lazer essential mix free download Stream Diplo & Switch aka Major Lazer - Essential Mix - July by A.M.B.O. from desktop or your mobile device. Stream Major Lazer [Switch & Diplo] - Essential Mix by A Ketch from desktop or your Krafty Kuts - Red Bull Thre3style Podcast (Free Download). Download major-lazer- essential-mix free mp3, listen and download free mp3 songs, major-lazer-essential-mix song download. Convert Youtube Major Lazer Essential Mix to MP3 instantly. Listen to Major Lazer - Diplo & Friends by Core News Join free & follow Core News Uploads to be the first to hear it. Join & Download the set here: Diplo & Friends Diplo in the mix!added 2d ago. Free download Major Lazer Essential Mix mp3 for free. Major Lazer on Diplo and Friends on BBC 1Xtra (01 12 ) [FULL MIX DOWNLOAD]. Duration: Grab your free download of Major Lazer Essential Mix by CRUCAST on Hypeddit. Diplo FriendsFlux Pavillion one Hour Mix on BBC Radio free 3 Essential Mix - Switch & Diplo (aka Major Lazer) Essential MixSwitch. DJ Snake has put up his awesome 2 hour Essential Mix up for free You can stream DJ Snake's Essential Mix below and grab that free download so you can . Major Lazer, Travis Scott, Camila Cabello, Quavo, SLANDER. Essential Mix:: Major Lazer:: & Scanner by Scanner Publication date Topics Essential Mix. DOWNLOAD FULL MIX HERE: ?showtopic= Essential Mix. Track List: Diplo Mix: Shut Up And Dance 'Ravin I'm Ravin' Barrington Levy 'Reggae Music Dub. No Comments. See Tracklist & Download the Mix! Diplo and Switch (original Major Lazer) – BBC Essential Mix – Posted in: , BBC Essential.