5 Lyon WC FE.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sr. No College Name District Gender Division Contact 1 GOVT

Sr. College Name District Gender Division Contact No 1 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 572613336 2 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN FATEH JANG, ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 572212505 3 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN PINDI GHEB, ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 4 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, JAND ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 572621847 5 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN HASSAN ABDAL ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 6 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN HAZRO, ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 572312884 7 GOVT. POST GRADUATE COLLEGE ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 579316163 8 Govt. Commerce College, Attock ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 9 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FATEH JANG ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 10 GOVT. INTER COLLEGE OF BOYS, BAHTAR, ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 11 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE (BOYS) PINDI GHEB ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572352909 12 Govt. Institute of Commerce, Pindigheb ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572352470 13 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE BOYS, JAND, ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572622310 14 GOVT. INTER COLLEGE NARRAH KANJOOR CHHAB ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572624005 15 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE BASAL ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572631414 16 Govt. Institute of Commerce, Jand ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572621186 17 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR BOYS HASSAN ABDAL, ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 18 GOVT.SHUJA KHANZADA SHAHEED DEGREE COLLEGE, HAZRO, ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572312612 19 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN CHAKWAL CHAKWAL Female RAWALPINDI 543550957 20 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN , DHADIAL , CHAKWAL CHAKWAL Female RAWALPINDI 543590066 21 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN MULHAL MUGHLAN, CHAKWAL CHAKWAL Female RAWALPINDI 543585081 22 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN BALKASSAR , CHAKWAL CHAKWAL Female RAWALPINDI 543569888 23 Govt Degree College for women Ara Basharat tehsil choa Saidan Shah chakwal CHAKWAL Female RAWALPINDI 543579210 24 GOVT. -

District ATTOCK CRITERIA for RESULT of GRADE 5

District ATTOCK CRITERIA FOR RESULT OF GRADE 5 Criteria ATTOCK Punjab Status Minimum 33% marks in all subjects 88.47% 88.32% PASS Pass + Minimum 33% marks in four subjects and 28 to 32 marks Pass + Pass with 88.88% 89.91% in one subject Grace Marks Pass + Pass with Pass + Pass with grace marks + Minimum 33% marks in four Grace Marks + 96.33% 96.72% subjects and 10 to 27 marks in one subject Promoted to Next Class Candidate scoring minimum 33% marks in all subjects will be considered "Pass" One star (*) on total marks indicates that the candidate has passed with grace marks. Two stars (**) on total marks indicate that the candidate is promoted to next class. PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, RESULT INFORMATION GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: ATTOCK Students Students Students Pass % with Pass + Promoted Pass + Gender Registered Appeared Pass 33% marks Students Promoted % Male 10474 10364 8866 85.55 9821 94.76 Public School Female 11053 10988 10172 92.57 10772 98.03 Male 4579 4506 3882 86.15 4313 95.72 Private School Female 3398 3370 3074 91.22 3298 97.86 Male 626 600 426 71.00 533 88.83 Private Candidate Female 384 369 295 79.95 351 95.12 30514 30197 26715 PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: ATTOCK Overall Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 11-138-126 Hadeesa Noor Ul Ain 482 1st 11-153-207 Shams Ul Ain 482 1st 11-138-221 Ia Eman 478 2nd 11-138-290 Manahil Khalid 477 3rd PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: ATTOCK Male Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 11-162-219 Muhammad Hasan Ali 476 1st 11-262-182 Raja Mohammad Bilal 475 2nd 11-135-111 Hammad Hassan 473 3rd PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: ATTOCK FEMALE Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 11-138-126 Hadeesa Noor Ul Ain 482 1st 11-153-207 Shams Ul Ain 482 1st 11-138-221 Ia Eman 478 2nd 11-138-290 Manahil Khalid 477 3rd j b i i i i Punjab Examination Commission Grade 5 Examination 2019 School wise Results Summary Sr. -

ATTOCK Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) Punjab 2007-08

Volume 30 ATTOCK Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) Punjab 2007-08 VOLUME -30 ATTOCK GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT BUREAU OF STATISTICS MARCH 2009 Contributors to the Report: Bureau of Statistics, Government of Punjab, Planning and Development Department, Lahore UNICEF Pakistan Consultant: Manar E. Abdel-Rahman, PhD M/s Eycon Pvt. Limited: data management consultants The Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey was carried out by the Bureau of Statistics, Government of Punjab, Planning and Development Department. Financial support was provided by the Government of Punjab through the Annual Development Programme and technical support by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). The final reportreport consists consists of of 36 36 volumes volumes. of whichReaders this may document refer to is the the enclosed first. Readers table may of contents refer to thefor reference.enclosed table of contents for reference. This is a household survey planned by the Planning and Development Department, Government of the Punjab, Pakistan (http://www.pndpunjab.gov.pk/page.asp?id=712). Survey tools were based on models and standards developed by the global MICS project, designed to collect information on the situation of children and women in countries around the world. Additional information on the global MICS project may be obtained from www.childinfo.org. Suggested Citation: Bureau of Statistics, Planning and Development Department, Government of the Punjab - Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, Punjab 2007–08, Lahore, Pakistan. ii MICS PUNJAB 2007-08 FOREWORD Government of the Punjab is committed to reduce poverty through sustaining high growth in all aspects of provincial economy. An abiding challenge in maintaining such growth pattern is concurrent development of capacities in planning, implementation and monitoring which requires reliable and real time data on development needs, quality and efficacy of interventions and impacts. -

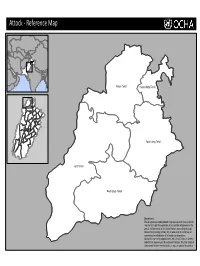

Reference Map

Attock ‐ Reference Map Attock Tehsil Hasan Abdal Tehsil Punjab Fateh Jang Tehsil Jand Tehsil Pindi Gheb Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Bahawalnagar‐ Reference Map Minchinabad Tehsil Bahawalnagar Tehsil Chishtian Tehsil Punjab Haroonabad Tehsil Fortabbas Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. p Bahawalpur‐ Reference Map Hasilpur Tehsil Khairpur Tamewali Tehsil Bahawalpur Tehsil Ahmadpur East Tehsil Punjab Yazman Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Planning Report Fateh Jang

PUNJAB MUNICIPAL DEVELOPMENT FUND COMPANY PUNJAB MUNICIPAL SERVICES IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (PMSIP) PLANNING REPORT FATEH JANG November 2007 TABLE O F CONTENTS Chapter I Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 PMSIP Planning 1 1.3 Limitations of PMSIP Planning 2 1.4 The Planning Process 2 1.5 Methodology 4 Chapter II Profile of Fateh Jang 6 2.1 General 6 2.2 Location 6 2.3 Area/Demography 6 Chapter III Institutional Analysis of TMA Fateh Jang 3.1 Capacity Building at TMA Fateh Jang 8 3.2 PMSIP Computer Trainings 8 3.3 Hands on Trainings for Complaint Resolution 9 3.4 Performance Management System 9 3.5 Financial Management System 11 3.6 Management Analysis 13 Chapter IV Urban Planning 4.1 TO(P) Office 14 4.2 Mapping 14 4.3 Land use Characteristics 16 4.4 City Zones 17 4.5 Housing Typologies 17 4.6 Growth Directions 18 Chapter V Status of Municipal Infrastructure & Recommendations 19 5.1 Road Network 19 5.2 Water Supply 20 5.3 Sewerage 25 5.4 Street Lights 29 5.5 Solid Waste Management 29 5.6 Fire Fighting 35 5.7 Parks 38 5.8 Slaughter House 40 Chapter VI Workshop on Prioritization of Infrastructure Sub-Projects 44 6.1 Pre-Workshop Consultations 44 6.2 Workshop Proceedings 44 6.3 Prioritized List of Sub-Projects 46 Annexes Annex-A Road Data 48 Annex-B Water Supply Data 49 Annex-C Sewerage Data 51 Annex-D Solid Waste Data 52 Punjab Municipal Services Improvement Project (PMSIP) ii Fateh Jang Urban Development Report LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Population forecast for Fateh Jang Table 2: Staff Trained under PMSIP Table 3: The details of Workshops / -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Attock

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT ATTOCK AUDIT YEAR 2012-13 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS......................................................................................................... I PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................... III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... IV SUMMARY TABLE & CHARTS........................................................................................................ VIII TABLE 1: AUDIT WORK STATISTICS ........................................................................................... VIII TABLE 2: AUDIT OBSERVATIONS CLASSIFIED BY CATEGORY ...................................... VIII TABLE4: IRREGULARITIES POINTED OUT ................................................................................... IX CHAPTER 1 .................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 DISTRICT GOVERNMENT ATTOCK ................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 INTRODUCTION OF DEPARTMENTS ................................................................................. 1 1.1.2 COMMENTS ON BUDGET AND ACCOUNTS (VARIANCE ANALYSIS) .................. 1 1.1.3 BRIEF COMMENTS ON THE STATUS OF COMPLIANCE WITH -

Rawalpindi Division NIC Applicantname Guardianname Address Winorder

Winner List Chief Minister Self Employment Scheme for Unemployed Educated Youth Rawalpindi Division NIC ApplicantName GuardianName Address WinOrder Distt. Attock Attock (Bolan) Key Used: sas91117 3710409582635 MUHAMMAD ASHFAQ MUHAMMAD NAWAZ P/O. GHARBI BASAL TEHSIL JAND 1 DISTT. ATTOCK 3710194732977 Muhammad Khalid Muhammad Idress House No.27, B Block Attock City. 2 3710117637067 IMRAN ALI HAJI SHER BAHADUR P/O. GOLRA DISTT. ATTOCK 3 3710167205235 IMTAZ AHMAD MUSTAQ AHMAD H NO. 381 SADDAR BAZZAR ATTOCK 4 CANTT 3710199615683 RAZI KHAN WARIS KHAN NEW ABADI QaSIM ABAD MIRZA P/O 5 SANJWAL CANTT DISTT 3710176505597 UMAIR AKHTAR AKHTAR HUSSAIN BHATTI H # 19 LANE # 2 6 GULHSANEKHUDADAD PHASE 5 3710126938959 ABDUL WAHEED AHMAD RUSTAM KHAN MOH.NASIR ABAD NEAR MASJID 7 KHATTAK FAROOQ E AZAM, DHOKE F 3710119531133 MUHAMMAD SALMAN IQBAL MUHAMMAD IQBAL MOHALA MADNI COLONY ZAFAR 8 ABBAD SANJWAL CANTT 3710130709617 JEHANGIR ABBAS GHULAM ABBAS H.NO.371, ST.NO.4, MOH. CHOIWEST 9 ATTOCK 3710117436007 MALIK RASHID MALIK FAZAL KHAN MOH. AMIN ABAD ST. NO.1 ATTOCK 10 3130235490949 Muhmmad Arshad Ghulam husain sial Mahalla Muhammad Abad p/o khan Bela 11 Teh. Liqauat p 3810408253813 M.SANA ULLAH JEEWAN KHAN GONDLAN WALA PO GOHAR WALA 12 TEH MANKERA 3710136961769 RIZWAN KHAN UMER KHAN D.S.G GATE MOHALLA SHAH NAGAR 13 SANWAL CANTT. DISTT. 3710117374349 MUHAMMAD DAUD MUHAMMAD FAROOQ MOHALA MUHAMMAD NAGAR SADAR 14 BAZAR ATTOCK 3710103070035 IMRAN ASLAM AWAN MUHAMAMD ASLAM AWAN MOH. NASIRABAD, H.NO.BXII 1525, 15 DHOKE FATEH ATTOCK 6110162800329 ARSHAD MEHMOOD MEHMOOD BLOCK NO.10 FLAT 14 CATEGORE V 16 SECTOR I-9/4 ISLAMA 3710107683223 FAISAL NAVEED NAVEED ISLAM VILLAGE MARI KANJOOR TEHSIL& 17 DISTT. -

Branchoperational.Pdf

S# Branch Code Branch Name Branch Adress City 1 24 Abbottabad Branch Mansera Road Abbottabad Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwarabad, Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad, Abbotabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad Abbottabad 4 721 Mansehra Road, Abbotabad Lodhi Golden Tower Supply Bazar Mansehra Road Abbottabad Abbottabad 5 721A PMA Kakul Abbottabad IJ-97, Near IJ Check Post, PMA Kakul, Abbottabad. Abbottabad 6 351 Ali Pur Chatha Near Madina Chowk, Ali Pur Chattha Ali Pur Chattha 7 266 Arifwala Plot # 48, A-Block, Outside Grain Market, Arifwala Arifwala 8 197 Attock City Branch Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City Attock 9 318 Khorwah, District Badin survey No 307 Main Road Khurwah District Badin Badin 10 383 Badyana Pasrur Road Badyana, District Sialkot. Badyana 11 298 Bagh, AJ&K Kashmir Palaza Hadari Chowk BAGH, Azad Kashmir BAGH AJK 12 201 Bahawalnagar Branch Grain Market Minchanabad Road Bahawalnagar Bahawalnagar 13 305 Haroonabad Plot No 41-C Ghalla Mandi, Haroonabad District Bahawalnagar Bahawalnagar 14 25 Noor Mahal Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 15 134 Channi Goth Bahawalpur Uch Road Channi Goth Tehsil Ahmed Pur East Bahawalpur 16 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur 17 269 UCH Sharif, District Bahawalpur Building # 68-B, Ahmed Pur East Road, Uch Sharif, Distric Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 18 390 Grain Market, Model Town-B, Bahawalpur Plot No. 112/113-B, Model Town-B, Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 19 750 IBB Circular Rd Bhawalpur Khewat No 38 Ground & First floor Aziz House Rafique Sabir Building Circular Road Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 20 258 Bannu Mir Afzal Khan Plaza, Outside Lucky Gate, Bannu Bannu 21 258A Bannu Cantt Shop No. -

Data Collection Survey on Renewable Energy Development in Pakistan

Data CollectionSurveyonRenewableEnergyDevelopmentinPakistan Islamic Republic of Pakistan Alternative Energy Development Board Data Collection Survey on Renewable Energy Development in Pakistan Final Report FINAL REPORT January 2013 January 2013 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. 4R JR 13-005 Data CollectionSurveyonRenewableEnergyDevelopmentinPakistan Islamic Republic of Pakistan Alternative Energy Development Board Data Collection Survey on Renewable Energy Development in Pakistan Final Report FINAL REPORT January 2013 January 2013 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. 4R JR 13-005 Data Collection Survey on Renewable Energy Development in Pakistan Final Report Location Map Islamabad Capital Territory Lahore Punjab Province Pakistan Sindh Province Karachi Source: Prepared by JICA Study Team based on the map downloaded at http://www.freemap.jp/ January 2013 i Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. Data Collection Survey on Renewable Energy Development in Pakistan Final Report SUMMARY 1. Background Pakistan is facing the acute electricity shortage. The gap between the estimated peak demand and the recorded peak supply of electricity in 2010 was around 5,000 MW. The gap between demand and supply in 2012 is estimated at more than 7,000 MW with the forecasted peak demand in 2012. This shortage of electricity supply affects harmfully daily life of the people and economic activities in Pakistan. The Government of Pakistan (GOP) addresses the resolution of electricity shortage as urgent issue. As the countermeasure of the resolution, the GOP placed the policy to make the electricity sources of Pakistan be diversified by developing indigenous resources: coal, large hydro power, and renewable energy (RE). 2. Objectives and Scope of the Study This survey aims to comprehensively collect data and information regarding the development of RE in Pakistan, and explore the possibility of cooperation by Japan for disseminating renewable energy. -

Attock Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (ATTOCK DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH ATTOCK DISTRICT 1,883,556 306,649 ATTOCK TEHSIL 434,705 69,049 ATTOCK CANTT 25,696 3590 CHARGE NO 01 25,696 3590 CIRCLE NO 01 13,211 1460 102010101 6,075 302 102010102 2,238 365 102010103 905 159 102010104 1,339 215 102010105 1,163 181 102010106 1,491 238 CIRCLE NO 02 4,072 684 102010201 557 99 102010202 679 125 102010203 1,840 303 102010204 996 157 CIRCLE NO 03 3,509 647 102010301 696 118 102010302 769 149 102010303 1,164 210 102010304 613 125 102010305 267 45 CIRCLE NO 04 4,904 799 102010401 1,146 177 102010402 649 128 102010403 1,334 210 102010404 1,775 284 ATTOCK I QH 111,812 17500 BOLIANWAL PC 10,031 1536 ARANG 1,232 186 101010807 1,232 186 BOLIANWAL 5,169 755 101010801 1,357 166 101010802 1,507 214 101010803 983 148 101010804 1,322 227 DAURDAD 1,994 304 101010806 1,994 304 SAKKABAD 1,636 291 101010805 1,636 291 CHOI GARIALA PC 9,935 1632 BAGH NILAB 1,135 180 101010304 293 48 101010305 842 132 CHOI GARIALA 3,015 512 Page 1 of 53 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (ATTOCK DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 101010301 1,318 205 101010302 1,109 209 101010303 588 98 SOJHANDA BHATA 5,785 940 101010306 2,285 331 101010307 696 135 101010308 506 96 101010309 867 164 101010310 1,431 214 DAKHNER PC 6,706 1015 DAKHNER 4,335 622 101010101 1,669 247 101010102 757 121 101010103 707 92 101010104 290 44 101010105 912 118 NOOR PUR KARAM ALIA 271 38 101010109 271 38 ROOMIAN 2,100 355 101010106 1,195 -

Attock, 5/12/1977 F.A 14/07/2014 Punjab

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE NAME BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 21689 IMTIAZ AHMED SHER ZAMAN V.P.O. SULTAN PURTEH.HASSAN ABDAL, ATTOCK, 5/12/1977 F.A 14/07/2014 PUNJAB 2 22043 MUHAMMAD RIAZ NOOR MOH AJA KHAIL V.P.O SHINKA TEHM HAZRODISTT, 8/12/1958 MATRIC 14/07/2014 MUHAMMAD ATTOCK, PUNJAB 3 36102 MUHAMMAD GHULAM DISTT. ATTOCK TEH, P/O PINDI GHEB VILLDHOKE 20-4-1976 MATRIC 15/7/2014 SABIR MUHAMMAD INAYAT ATTOCK, ATTOCK, PUNJAB 4 49528 RIZWAN AHMED IFTIKHAR UD MOH, ANDROON HASSAN ABAD DISTT,, ATTOCK, 10-5-1974 MA 21/07/2014 DIN PUNJAB 5 25384 JAMSHAID KAINOOR MOH, MELUD NAGAR H ABADAL , ATTOCK, PUNJAB 17-4-1979 MATRIC 07/08/2014 6 29782 MASOOD-UL- MANZOOR H NO. 3/101 MASJID MIAN NOOR TEH, ROADFATEH 26-1-1977 MATRIC 13/09/2014 HASSAN HASSAN JHANG , ATTOCK, PUNJAB 7 22266 MUHAMMAD KHAN VILL.&P.O. RINGO MOHALLAH BARATEH.&DISTT.,, 15/4/1961 MATRIC 26/09/2014 AFZAL BAHADAR ATTOCK, PUNJAB 8 35397 NAZIAM HUSSAIN ABDUL VILL BEHI PO AONBISARDHATA TEH &KUTLI, 1/4/1953 F.A 3/10/2014 SHAH HUSSAIN SHAH ATTOCK, PUNJAB 9 22294 GUL ZARIN GUL JAHAN VILL.MUGAM HADOO WALIP.O. INJRA TEH.PINDI 1/8/1956 MATRIC 09/10/2014 SAGHRI GHEB, ATTOCK, PUNJAB 10 46287 MUHAMMAD GHULAM P.O & TEH HASSAN ABDAL DISTT ATTOCK, ATTOCK, 18/03/1983 MATRIC 29/10/2014 ZUBAIR GALANI PUNJAB 11 39130 MUHAMMAD IRSHAD MOH, CHHOI EAST N.R PWER HOUSE , ATTOCK, 27-11-1971 FA 01/11/2014 ASAD MUHAMMAD PUNJAB 12 37134 SHAGUFTA MAULA NEAR AWAISIA MASJID DHOK FATEH ATTO, 29-6-1982 MATRIC 8/11/2014 NASREEN BAKHSH ATTOCK, PUNJAB 13 22401 SAJID HUSSAIN GHULAM VILL PO KOT CHAJJITEH JAND, ATTOCK, PUNJAB 3/12/1960 MATRIC 12/11/2014 QADIR 14 26105 RASHID KHAN SARWAR KHAN VILL P/O BURHAU HUSSAIN ABDAL DISTT,ATTOCK, 5-10-1980 FA 15/11/2014 ATTOCK, PUNJAB 15 38696 RAZI ABBAS SYED GILANI DAWA KHANA FATEH JHANG DISTTATTOCK, 7-10-1980 MATRIC 28/11/2014 SHAH MHUTAJAB ATTOCK, PUNJAB SHAH 16 25957 UMER JAVED MUHAMMAD H NO. -

Tackling Unmet Needs for Major Obstetric Interventions Case Studies

Tackling Unmet Obstetric Needs: Pakistan Tackling Unmet Needs for Major Obstetric Interventions Case studies Pakistan CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS............................................................................................................................... 2 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 3 2. CONTEXT................................................................................................................................... 3 General ................................................................................................................................... 3 Maternal health policy........................................................................................................... 4 3. THE UON EXERCISE .................................................................................................................. 7 Equipment and Method ......................................................................................................... 8 The data base....................................................................................................................... 11 Results.................................................................................................................................. 14 4. UTILISATION OF RESULTS.......................................................................................................... 23 Retro-information ...............................................................................................................