Associational Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

(COP 19) Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining

STANDARD GUIDANCE (COP 19) Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining A. Definitions and applicability Freedom of association is the right of workers and employers to freely form and join Workers Organisations such as trade unions, worker associations and worker councils or committees for the promotion and defence of occupational interests. Collective bargaining is a process through which employers (or their organisations) and workers’ associations (or in their absence, freely designated workers’ representatives) negotiate terms and conditions of work. Both are fundamental rights and they are linked. Collective bargaining cannot work without freedom of association because workers’ views cannot be properly represented. Workers must be free to choose whether and how they are to be represented and employers must not interfere in this process. A Collective Bargaining Agreement is a legally enforceable written contract between the management of a company and its employees, represented by a Workers Organisation, that defines terms and conditions of work. Collective bargaining agreements must comply with Applicable Law. A Workers Organisation is a voluntary association of workers organised on a continuing basis for the purpose of maintaining and improving their terms of employment and workplace conditions. Source: ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work http://www.ilo.org/declaration/principles/freedomofassociation/lang--en/index.htm ILO Better Work, Guidance Sheet 4: Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining http://betterwork.com/global/wp-content/uploads/4-Freedom-of-Association.pdf RJC Code of Practices (2013) The Freedom of Association and Collective Bargaining section of the COP is applicable to all Members with employees. B. Issue background The right to freedom of association is proclaimed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. -

Right to Freedom of Association in the Workplace: Australia's Compliance with International Human Rights Law

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title The Right to Freedom of Association in the Workplace: Australia's Compliance with International Human Rights Law Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/98v0c0jj Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 27(2) Author Hutchinson, Zoé Publication Date 2010 DOI 10.5070/P8272022218 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLES THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION IN THE WORKPLACE: AUSTRALIA'S COMPLIANCE WITH INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW Zoe Hutchinson BA LLB (Hons, 1st Class)* ABSTRACT The right to freedom of association in the workplace is a well- established norm of internationalhuman rights law. However, it has traditionally received insubstantial attention within human rights scholarship. This article situates the right to freedom of as- sociation at work within human rights discourses. It looks at the status, scope and importance of the right as it has evolved in inter- nationalhuman rights law. In so doing, a case is put that there are strong reasons for states to comply with the right to freedom of association not only in terms of internationalhuman rights obliga- tions but also from the perspective of human dignity in the context of an interconnected world. A detailed case study is offered that examines the right to free- dom of association in the Australian context. There has been a series of significant changes to Australian labor law in recent years. The Rudd-Gillard Labor government claimed that recent changes were to bring Australia into greater compliance with its obligations under internationallaw. This policy was presented to electors as in sharp contrast to the Work Choices legislation of the Howard Liberal-Nationalparty coalitiongovernment. -

Liberalism and the Charter: Freedom of Association and the Right to Strike

Dalhousie Journal of Legal Studies Volume 5 Article 5 1-1-1996 Liberalism and the Charter: Freedom of Association and the Right to Strike Terry Sheppard Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/djls This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Recommended Citation Terry Sheppard, "Liberalism and the Charter: Freedom of Association and the Right to Strike" (1996) 5 Dal J Leg Stud 117. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Schulich Law Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dalhousie Journal of Legal Studies by an authorized editor of Schulich Law Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIBERALISM AND THE CHARTER: FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION AND THE RIGHT TO STRIKE TERRY SHEPPARDt Liberalism, for the most part, has been opposed to unions because they are perceived to be opposed to individualism and detrimental to the free market. This paper will attempt to show how union rights, and more particularly the right to strike, can be accomodated in the liberal philosophy. As a preliminary matter, some principal tenets of liberal theory are examined: ethical individualism; the concept of liberty as negative liberty; the focus on individuals rather than groups as the locus of rights; and a desire to restrain the actions ofgovernment. The paper then proceeds to use liberal philosophy to critique decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada denying Charter protection to the right to strike. The right to strike, it is concluded, is more aptly phrased a freedom to strike. -

Freedom of Association and the Private Club: the Installation of a "Threshold" Test to Legitimize Private Club Status in the Public Eye Julie A

Marquette Law Review Volume 72 Article 3 Issue 3 Spring 1989 Freedom of Association and the Private Club: The Installation of a "Threshold" Test to Legitimize Private Club Status in the Public Eye Julie A. Moegenburg Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Julie A. Moegenburg, Freedom of Association and the Private Club: The Installation of a "Threshold" Test to Legitimize Private Club Status in the Public Eye, 72 Marq. L. Rev. 403 (1989). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol72/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION AND THE PRIVATE CLUB: THE INSTALLATION OF A "THRESHOLD" TEST TO LEGITIMIZE PRIVATE CLUB STATUS IN THE PUBLIC EYE I. INTRODUCTION The most natural privilege of man, next to the right of acting for himself, is that of combining his [energy, ideas and dreams] with those of his fellow creatures and of acting in common with them. The right of association therefore appears to me almost as inaliena- ble in its nature as the right of personal liberty.... Nevertheless, if the liberty of association is only a source of advantage and prosper- ity to some nations, it may be perverted or carried to excess by others, and from an element of life may be changed into a cause of destruction.1 For more than three decades,2 courts have recognized a right to associ- ate freely with others in pursuit of a wide variety of political, social, eco- nomic, educational, religious, and cultural objectives.3 Recently, the Supreme Court has crystallized two distinct aspects of freedom of associa- tion: freedom of intimate association and freedom of expressive association. -

Expressive Association and Anti-Discrimination Law After Dale: a Tripartite Approach

Scholarship Repository University of Minnesota Law School Articles Faculty Scholarship 2001 Expressive Association and Anti-Discrimination Law After Dale: A Tripartite Approach Dale Carpenter University of Minnesota Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dale Carpenter, Expressive Association and Anti-Discrimination Law After Dale: A Tripartite Approach, 85 MINN. L. REV. 1515 (2001), available at https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles/146. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in the Faculty Scholarship collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Expressive Association and Anti-Discrimination Law After Dale: A Tripartite Approach Dale Carpentert Is Dale' a disaster? To many who support equal civil rights for gay people, it certainly seems so. 2 In Dale, after all, the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment allowed the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) to exclude an openly gay scoutmaster despite a state law forbidding such discrimination.3 More broadly, the rationale for the decision-based on the BSA's right of expressive asso- ciation-has raised fears (for some, hopes) that the Court might be moving toward a sweeping review of the constitutionality of numerous state and federal statutes forbidding discrimination in business-related clubs, public accommodations, and even employment. 4 At the very least, Dale may have called a consti- t Associate Professor of Law, University of Minnesota; former Boy Scout. -

Brief Amici Curiae of First Amendment and Election Law Scholars Filed

No. 18-422, 18-726 In the Supreme Court of the United States ROBERT A. RUCHO, ET AL., Appellants, v. COMMON CAUSE, ET AL., Appellees. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina LINDA H. LAMONE, ET AL., Appellants, v. O. JOHN BENISEK, ET AL., Appellees. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Maryland BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE FIRST AMEND- MENT AND ELECTION LAW SCHOLARS IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES BRADLEY S. PHILLIPS Counsel of Record GREGORY D. PHILLIPS MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP 350 South Grand Ave 50th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90071 [email protected] (213) 683-9100 Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ...................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .......................... 1 ARGUMENT ..................................................... 5 A. The Right of Association Protects an Individual’s Ability to Enhance Her Political Influence by Associating with Others .............. 5 B. The Right of Association Forbids Districting that Discriminatorily Burdens Political Association Based on Party Affiliation......... 12 C. North Carolina’s Redistricting Plan Violates Plaintiffs’ Associational Rights .................. 22 D. Maryland’s Redistricting Plan Violates Plaintiffs’ Associational Rights. ........................................ 26 CONCLUSION ............................................... 28 APPENDIX OF AMICI CURIAE ....................1a ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) CASES Anderson v. Celebrezze, 460 U.S. 780 (1986) .......................................passim Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516 (1960) .............................................. 16 Branti v. Finkel, 445 U.S. 507 (1980) ................................................ 8 Burdick v. Takushi, 504 U.S. 428 (1992) .......................................passim Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996) ........................................ 20, 21 California Democratic Party v. Jones, 530 U.S. 567 (2000) ....................................... -

Joint Guidelines on Freedom of Association

Strasbourg, Warsaw, 17 December 2014 CDL-AD(2014)046 Or. Engl. Study no. 706/2012 OSCE/ODIHR Legis-Nr: GDL-FOASS/263/2014 EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) OSCE OFFICE FOR DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS (OSCE/ODIHR) JOINT GUIDELINES ON FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 101st Plenary Session (Venice, 12-13 December 2014) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int - 2 - CDL-AD(2014)046 Published by the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Miodowa 10 00-557 Warsaw Poland www.osce.org/odihr © OSCE/ODIHR 2015 ISBN 978-92-9234-906-6 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non- commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of ODIHR as the source. Cover and interior designed by Nona Reuter Printed in Poland by Poligrafus Jacek Adamiak - 3 - CDL-AD(2014)046 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 5 WORK OF THE OSCE/ODIHR AND THE VENICE COMMISSION ON LEGISLATIVE SUPPORT 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 7 INTRODUCTION 8 SECTION A: THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION 10 Introduction 10 Definition of associations ................................................................................................................... 12 Importance of associations ............................................................................................................... 12 Fundamental rights of associations ................................................................................................. -

Repression Falls on Those Who Struggle So It Also

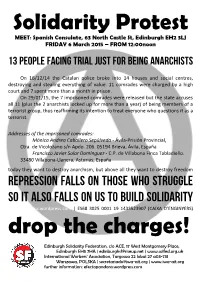

Solidarity Protest MEET: Spanish Consulate, 63 North Castle St, Edinburgh EH2 3LJ FRIDAY 6 March 2015 – FROM 12:00noon 13 PEOPLE FACING TRIAL JUST FOR BEING ANARCHISTS On 16/12/14 the Catalan police broke into 14 houses and social centres, destroying and stealing everything of value. 11 comrades were charged by a high court and 7 spent more than a month in prison. On 29/01/15, the 7 imprisoned comrades were released but the state accuses all 11 (plus the 2 anarchists locked up for more than a year) of being members of a terrorist group, thus reaffirming its intention to treat everyone who questions it as a terrorist. Addresses of the imprisoned comrades: Mónica Andrea Caballero Sepúlveda - Ávila-Prisión Provincial, Ctra. de Vicolozano s/n Apdo. 206. 05194 Brieva, Ávila, España Francisco Javier Solar Domínguez - C.P. de Villabona Finca Tabladiello. 33480 Villabona-Llanera, Asturias, España today they want to destroy anarchism, but above all they want to destroy freedom REPRESSION FALLS ON THOSE WHO STRUGGLE SO IT ALSO FALLS ON US TO BUILD SOLIDARITY efectopandora.wordpress.com | ES68 3025 0001 19 1433523907 (CAIXA D'ENGINYERS) drop the charges! Edinburgh Solidarity Federation, c/o ACE, 17 West Montgomery Place, Edinburgh EH5 7HA | [email protected] | www.solfed.org.uk International Workers’ Association, Targowa 22 lokal 27 a03-731 Warszawa, POLSKA | [email protected] | www.iwa-ait.org further information: efectopandora.wordpress.com the terrorist is the capitalist state ‘Operación Pandora’ is a deliberate attempt to intimidate and criminalise the libertarian movement, which has been pursued by the Spanish Audiencia Nacional [a special unit of the judiciary to combat "terrorism"] and the Catalonian police. -

Freedom of Association in the Wake of Coronavirus

Legal Sidebari Freedom of Association in the Wake of Coronavirus April 16, 2020 At least 42 U.S. states have issued emergency orders directing residents to “stay at home,” with many states prohibiting gatherings of various sizes to control the spread of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID- 19). California’s March 19th stay-at-home order effectively banned public gatherings outside of “critical” sectors and “essential” services. New York’s March 23rd order “canceled or postponed” “non-essential gatherings of individuals of any size for any reason (e.g. parties, celebrations or other social events),” with a maximum penalty of $1,000 for violations added in a later order. Maryland’s March 30th order prohibited “[s]ocial, community, spiritual, religious, recreational, leisure, and sporting gatherings and events . of more than 10 people,” with willful violators facing up to a year imprisonment and/or a maximum fine of $5,000. Texas’s March 31st order directed residents to “minimize social gatherings” except “where necessary to provide or obtain” designated “essential services.” In late March, some lawmakers called on the President to issue a temporary, nationwide shelter-in-place order. Mandatory social distancing measures have prompted constitutional questions, including whether gathering bans, which restrict in-person communication, comport with the First Amendment’s protections for freedom of speech and assembly. There have already been a few legal challenges to COVID-19– related orders litigated on these grounds. On March 25th, a New Hampshire court denied an emergency motion to enjoin that state’s previous ban on scheduled gatherings of 50 people or more. -

Bogg, A. L. (2017). Individualism and Collectivism in Collective Labour Law. Industrial Law Journal, 46(1), 72-108

Bogg, A. L. (2017). Individualism and Collectivism in Collective Labour Law. Industrial Law Journal, 46(1), 72-108. https://doi.org/10.1093/indlaw/dww045 Peer reviewed version License (if available): Other Link to published version (if available): 10.1093/indlaw/dww045 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the accepted author manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via OUP at https://doi.org/10.1093/indlaw/dww045 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ 1 ‘INDIVIDUALISM’ AND ‘COLLECTIVISM’ IN COLLECTIVE LABOUR LAW ALAN BOGG* ABSTRACT This article examines the concepts of ‘individualism’ and ‘collectivism’ in collective labour law. A popular critique of freedom of association norms characterises such norms as ‘individualist’ or ‘individualistic’. This individualist bias undermines the institutions of collective labour relations. The 'individualist' critique is often coupled with the development of an alternative positive account of collective labour law that is based upon a foundation of ‘collectivism’. ‘Collectivist’ labour law encompasses a concern for collective or group rights, rather than rights for individuals; it affirms collective values; and the metric of legitimacy of a legal regime of freedom of association is the extent to which it supports collective bargaining through independent trade unions. On this conventional approach, ‘individualism’ and ‘collectivism’ stand in opposition to each other. -

How Fundamental Is the Freedom? — Section 2(D)

Chapter 2 Freedom of Association: How Fundamental is the Freedom? Ð Section 2(d) Paul J.J. Cavalluzzo and Adrienne Telford* 1. Introduction The recent Fraser v. Ontario (Attorney General)1 case demonstrates a lingering debate in the Supreme Court of Canada on the nature of freedom of association. It harkens back to the vigorous debate between Justice McIntyre and Chief Justice Dickson in the Reference re: Public Service Employee Relations Act,2 the court's first attempt to instantiate the abstract right to freedom of association under s. 2(d) of the Charter. This debate, in the early stages of the Charter, was won by Justice McIntyre who rendered a narrow interpretation of freedom of association by relying upon American constitutional doctrine with no reference to the material differences in the Canadian context. In particular, he relied upon American legal literature which focused upon the individual nature of freedom of association. In the U.S., freedom of association is conceived of as a narrow individual right in part because it is derived from the individual rights found in the First Amendment to the Bill of Rights. Unlike the Charter, the American Bill of Rights does not explicitly protect freedom of association. Justice McIntyre also relied upon two policy reasons to support his conclusion that the right to strike was not protected by s. 2(d) which related to the institutional limits of courts in reviewing labour laws. In a strong dissent, Chief Justice Dickson recognized the different legal and political culture in Canada which was recognized by our * Both of Cavalluzzo Hayes Shilton McIntyre & Cornish, Toronto.