Percussive Fingerstyle Guitar Through the Lens of NIME: an Interview Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack Pearson

$6.00 Magazine Volume 16, Number 2 January/February 2012 Jack Pearson Al Smith Nick DiSebastian Schenk Guitars 1 Flatpicking Guitar Magazine January/February 2012 design by [email protected] by “I am very picky about the strings I use on my Kendrick Custom Guitar, and GHS gives me unbeatable tone in a very long lasting string.” GHS Corporation / 2813 Wilber Avenue / Battle Creek . Michigan 49015 / 800 388 4447 2 Flatpicking Guitar Magazine January/February 2012 Block off February 23 thru the 26th!! Get directions to the Hyatt Regency in Bellevue, WA. Make hotel & travel arrangements. Purchase tickets for shows and workshops! Practice Jamming!! Get new strings! Bookmark wintergrass.com for more information! Tell my friends about who’s performing: Ricky Skaggs & Kentucky Thunder Tim O’Brien, The Wilders, The Grascals, The Hillbenders, Anderson Family Bluegrass and more!!! Practice Jamming!!!!! wintergrass.com 3 Flatpicking Guitar Magazine January/February 2012 Feb 23-26th 4 Flatpicking Guitar Magazine January/February 2012 1 Flatpicking Guitar Magazine January/February 2012 CONTENTS Flatpicking FEATURES Jack Pearson & “Blackberry Pickin’” 6 Guitar Schenk Guitars 25 Flatpick Profile: Al Smith & “Take This Hammer” 30 Magazine CD Highlight: Nick DiSebastian: “Snowday” 58 The Nashville Number System: Part 2 63 Volume 16, Number 2 COLUMNS January/February 2012 Bluegrass Rhythm Guitar: Homer Haynes 15 Published bi-monthly by: Joe Carr High View Publications Beginner’s Page: “I Saw the Light” 18 P.O. Box 2160 Dan Huckabee Pulaski, VA 24301 -

Training Your Musical Muse with Richard Gilewitz... an Exclusive

Training Your Musical Muse with Richard Gilewitz... an exclusive guitar and ukulele 1 day workshop for beginner/intermediate instrumentalists (guitar or ukulele) and singer/songwriters No matter if you play a guitar or ukulele, sing or don’t sing, compose originals or play covers, it’s all the same when teaching your musical muse the solid basics of good technique. During this 1-day workshop, you’ll learn about fingerpicking patterns and strumming, rhythm, why some notes work while others are a train wreck, and how to develop good habits that will protect your inner muse from the dole drum of sameness and predictability. Join master teacher, Richard Gilewitz, for an experience for both ukulele and guitar. These workshops offer players and/or singers the techniques for developing and expanding a life-long craft in a most satisfying direction. It’s an opportunity to witness and join in on the fun and challenges presented by learning new techniques and how the Gilewitz method works for both guitar and ukulele. Class Sessions will be 50 minutes each with group exercises and special attention to every student in the class. Each class is $30 10:00am Guitar Class1: The Fingerpicking Engine, Effective Chord Transfers, & Food Rhythm Gather the ingredients for the picking fingers with very simple patterns that can be applied to literally any genre of music. The components of the Fingerpicking Engine are the foundation for fingerstyle guitar. Study and explore fingering techniques that power this playing style that include banjo- style inside and forward rolls, pairing, pinch-patterns, hammer-ons, and pull-offs, classical arpeggios, tapping and harmonics, as well as effective method of incorporating rhythmic/strumming techniques within your picking patterns. -

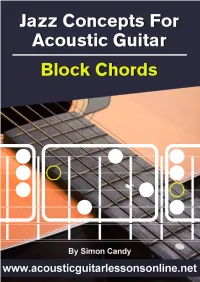

Jazz Concepts for Acoustic Guitar Block Chords

Jazz Concepts For Acoustic Guitar Block Chords © Guitar Mastery Solutions, Inc. Page !2 Table Of Contents A Little Jazz? 4 What Are Block Chords? 4 Chords And Inversions 5 The 3 Main Block Chord Types And How They Fit On The Fretboard 6 Major 7th ...................................................................................6 Dominant 7th ..............................................................................6 Block Chord Application 1 - Blues 8 Background ................................................................................8 Organising Dominant Block Chords On The Fretboard .......................8 Blues Example ...........................................................................10 Block Chord Application 2 - Neighbour Chords 11 Background ...............................................................................11 The Progression .........................................................................11 Neighbour Chord Example ...........................................................12 Block Chord Application 3 - Altered Dominant Block Chords 13 Background ...............................................................................13 Altered Dominant Chord Chart .....................................................13 Altered Dominant Chord Example .................................................15 What’s Next? 17 © Guitar Mastery Solutions, Inc. Page !3 A Little Jazz? This ebook is not necessarily for jazz guitar players. In fact, it’s more for acoustic guitarists who would like to inject a little -

Fingerstyle Guitar Arrangements

The Heritage Fingerstyle Guitar Arrangements Includes FREE CD! By Stuart Ryan The Heritage An Overview PICKING HAND TECHNIQUES There are several diferent approaches to the picking must ensure your fretting hand is clean and accurate hand that you will encounter in this book. Pieces so you can really keep these strings sounding. When like ‘Amazing Grace’ rely on the traditional ‘pima’ building your own arrangements you’ll fnd DADGAD is fngerpicking approach. In this system the thumb is ideal for pieces from the Irish and Scottish canon (and typically used to pluck the 6th, 5th and 4th strings whilst beyond) but you may come to a point where you fnd it the index, middle and ring fngers pluck 3rd, 2nd and always drags you to the key of D so make sure you try 1st strings respectively. Of course there are variations arranging in some other keys when using this tuning! on these patterns and sometimes the fngers move to diferent strings but if you come from a traditional Standard tuning is ideal for pieces requiring walking fngerpicking background then you will probably be basslines or chords that are commonly associated with already familiar with this approach. Other pieces like Gospel and Blues and you’ll fnd this used on pieces ‘Since I Lay My Burden Down’ rely on the traditional like ‘Amazing Grace’ and ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot.’ American blues/Travis picking system where the thumb A close cousin of Standard tuning is Drop D where the is used to pluck alternating basslines on the 6th, 5th and 6th string is lowered a tone from E to D. -

Tale of Two Champions Guitarists Muriel Anderson and Helen Avakian Will Display Their Winning Styles at the Towne Crier

May 20-26, 2015 Creative Living celebrating all good things Tale of two champions Guitarists Muriel Anderson and Helen Avakian will display their winning styles at the Towne Crier. by Kate Goldsmith compositions by Ralph Towner, George Muriel Anderson Gershwin, Stevie Wonder, Lennon & also Helen Avakian McCartney and Avakian, herself. There’s Friday, May 22, 8:30 p.m. also a dual-guitar arrangement by Peter Towne Crier Café Huttlinger of the traditional “Monaghan 379 Main St., Beacon Jig,” with a guest performance by Tickets $20 advance, $25 door Huttlinger. (845) 855-1300• www.townecrier.com As an arranger, Avakian takes songs that she loves, listens carefully to all the parts What are the chances of the only two and transcribes them. female fingerstyle guitar champions in the “After that I often will give it to a guitar world performing on the same bill in ensemble I am working with. This gives me Beacon, New York? a chance to see how the parts fit together Pretty good, as it happens. and sound on guitar,” she said. “That leads Muriel Anderson and Helen Avakian to tweaking the arrangement, fixing prob- will share the Towne Crier stage this Friday lems and maybe getting a new idea or two. evening, demonstrating why they are Then I figure out how to fit it all on one gui- among the best of the best. Each will per- tar as effectively as I can.” form a solo set and then join forces for a She records throughout the process, too, few tunes. “so I can listen from more of an outsider A longstanding popular presence on the observer point of view.” The performance Hudson Valley music scene, Avakian is an process tweaks the piece further until a accomplished singer-songwriter who was “standardized” version emerges. -

Acoustic Guitar

45 ACOUSTIC GUITAR THE CHRISTMAS ACOUSTIC GUITAR METHOD FROM ACOUSTIC GUITAR MAGAZINE COMPLETE SONGS FOR ACOUSTIC BEGINNING THE GUITAR GUITAR ACOUSTIC METHOD GUITAR LEARN TO PLAY 15 COMPLETE HOLIDAY CLASSICS METHOD, TO PLAY USING THE TECHNIQUES & SONGS OF by Peter Penhallow BOOK 1 AMERICAN ROOTS MUSIC Acoustic Guitar Private by David Hamburger by David Hamburger Lessons String Letter Publishing String Letter Publishing Please see the Hal Leonard We’re proud to present the Books 1, 2 and 3 in one convenient collection. Christmas Catalog for a complete description. first in a series of beginning ______00695667 Book/3-CD Pack..............$24.95 ______00699495 Book/CD Pack...................$9.95 method books that uses traditional American music to teach authentic THE ACOUSTIC EARLY JAZZ techniques and songs. From the folk, blues and old- GUITAR METHOD & SWING time music of yesterday have come the rock, country CHORD BOOK SONGS FOR and jazz of today. Now you can begin understanding, GUITAR playing and enjoying these essential traditions and LEARN TO PLAY CHORDS styles on the instrument that truly represents COMMON IN AMERICAN String Letter Publishing American music: the acoustic guitar. When you’re ROOTS MUSIC STYLES Add to your repertoire with done with this method series, you’ll know dozens of by David Hamburger this collection of early jazz the tunes that form the backbone of American music Acoustic Guitar Magazine and swing standards! The and be able to play them using a variety of flatpicking Private Lessons companion CD features a -

Review of Jim Bruce's Ragtime and Blues Guitar Picking Course

Review of Jim Bruce's Ragtime and Blues Guitar Picking Course Learn to Play Finger Style Acoustic Blues Guitar Something great has happened for anybody wanting to learn how to play acoustic blues guitar. It's called Jim Bruce Ragtime and Blues Guitar Picking Course - From Texas to the Delta. Now there's a mouthful! So what is it? Well, pretty much as the title says, it's a guitar course for learning how to play ragtime and blues finger style acoustic guitar. Before I go on, let me just say this isn't something for the absolute beginner guitarist. If you aren't yet comfortable or reasonably fluent in playing common chords, then you probably aren't ready for this just yet, unless you are hyper determined! About the Course The course is quite straightforward. It jumps straight in and shows you how to play a collection of 40 blues songs from blues guitarists such as Blind Blake, Robert Johnson and Big Bill Broonzy to name but a few. Each of the songs are shown on video (MP4 format), first at normal speed and then broken down into small sections, played slowly. The video also uses split screen for showing the left and right hands independently and displaying on screen Tabs and chord diagrams. All of the songs also come with a printable pdf file with the full guitar Tab. Although Jim offers a few tips in the videos, you are expected to know certain things like how to read guitar tab and are already familiar with the basic chords. -

Fingerstyle Chapter 1

FINGER STYLE GUITAR Fingerstyle Basics for Guitar NYC Guitar School ©2011 New York City Guitar School 251 West 30th Street ©2011 Lenny Molotov New York, NY 10001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may Publisher: Dan Emery be reproduced in any manner in any media, or Editor: Vince DeMasi transmitted by any means whatsoever, electronic Book design: Chika Azuma or mechanical (including photocopy, film or Photographer: Woody Quinn video recording. Internet posting, or any other Additional Photo (page 38) Chika Azuma information storage and retrieval system), without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN First edition Published in the United States by NYC Guitar School. Printed and Bound in the United States ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish I could name some teachers or mentors who personally initiated me into the secrets of fingerstyle guitar, but actually there are none. The knowledge put forth in this book was obtained through hours of hard listening—to the recordings of fingerpicking singer-songwriters and early blues and ragtime guitar- ists. With the listening went transcribing. Initially this was to learn this type of material myself, later it also became about teaching it to others. While teaching over the last 10 years I have been learning the essential principles of the fingerstyle art and figur- ing the best way to convey them. This process is under constant refinement. The book represents a crystallization of this process. More teaching methods today focus on chords or linear lines, riffs and soloing so I think it’s safe to say that there is a void in fingerstyle (non-classical) guitar education. -

Design of a Composite Guitar Master Thesis Report Max Roest

Technische Universiteit Delft Design of a composite guitar Master Thesis Report Max Roest Design of a composite guitar Master Thesis Report by Max Roest Student number: 4084217 Hand-in date: August 17, 2016 Supervisor: dr. ir. O.K. Bergsma, TU Delft Summary Today’s acoustic guitars are getting increasingly expensive due to the worsening availability of the highest quality woods. Composites show great promise in replacing wood in acoustic guitars as they are lightweight, are not as sensitive to environmental effects and are much stronger. Current composite guitars however do not sound as good as their wooden counterparts. Therefore this thesis research has been set-up to create a composite material that can match wood acoustically and therefore have all the benefits in terms of environ- mental sensitivity and strength while not compromising the sound quality of the instrument. A new com- posite is developed and extensively tested. This composite consists of a carbon fibre reinforced polyurethane foam and has a comparable acoustic response to high quality spruce used for guitar soundboards. With this new composite a complete composite guitar is designed, manufactured and tested. The psychoacoustic anal- ysis performed showed that the new composite guitar is considerably more wood like in its sound compared to current carbon fibre acoustic guitars. ii Preface Max Roest Delft, July 2016 It is over 20 years ago that I received my first guitar. A few months later, at the age of 4, I had my first guitar lessons. Now at the age of 24, it is hard to remember any period in my life where guitars and music have not played a major role in my life. -

(1984): Michael Hedges and the De/Reterritorialization of the Steel-String Acoustic Guitar

Marcel Bouvrie 4069277 | Beyond Aerial Boundaries (1984): Michael Hedges and the De/reterritorialization of the Steel-String Acoustic Guitar Beyond Aerial Boundaries (1984): Michael Hedges and the De/reterritorialization of the Steel-String Acoustic Guitar Marcel Bouvrie 4069277 Master thesis Applied Musicology July 2018 University Utrecht Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Emile Wennekes Contents: Introduction p. 2 Methodology p. 4 Chapter 1: Assemblage p. 8 Chapter 2: The Rhizome p. 13 Chapter 3: De/reterritorialization p. 20 Conclusion p. 31 Bibliography p. 33 1 Marcel Bouvrie 4069277 | Beyond Aerial Boundaries (1984): Michael Hedges and the De/reterritorialization of the Steel-String Acoustic Guitar Introduction In 1984, acoustic guitar virtuoso Michael Hedges released his second album, Aerial Boundaries, which many describe as the genesis of a new solo acoustic guitar movement:1 a movement where guitarists expand the sonic and musical palette of the acoustic guitar by optimally combining its melodic, harmonic, timbral and percussive potential. This, in order to develop the acoustic guitar as a fully-fledged solo instrument, rather than its more typical role of accompanying instrument. Before Hedges, there were already several acoustic guitarists who challenged the convention that the steel-string acoustic guitar’s primary function is that of an instrument for accompaniment. John Fahey, Leo Kottke, Will Ackerman and Preston Reed were the most prominent guitarists to try to validate the steel-string acoustic guitar as a solo instrument. They all had their own unique idiosyncratic approach within this self- proclaimed mandate, but none had the disruptive impact that Hedges had, and still has. Today, this new acoustic guitar movement – often described as Fingerstyle or Percussive Guitar – is larger and more popular than ever. -

Taylor Guitars Wood & Steel Magazine

INSIDE THE WORLD OF TAYLOR GUITARS / VOLUME 74 winter 2013 THE 2013 GUITAR GUIDE The New Grand Orchestra Big & Balanced Koa 200s Find Your Fit All About Shapes, Woods & Sounds Your Player Profile Sustainable Forestry String-Changing Tips Taylor Around the World 2 www.taylorguitars.com 3 Letters Volume 74 Winter 2013 Find us on Facebook. Subscribe on YouTube. Follow us on Twitter: @taylorguitars the eye of the hurricane passed over around the block, so to speak. We lor sales managers Michael Lille and the beauty and the fullness of the us and spared us the non-stop winds were overwhelmed by the knowledge, Aaron Dablow, and product specialist sound coming from such a small guitar. and torrential rain that afflicted the sense of humor, and musical abilities of Marc Seal] played three different Taylor I knew I had to have one. areas farther north. We did, however, both people putting on the show [Ed. guitar shapes with different woods My wife and I do a great deal of suffer two high-tide storm surges that Note: Taylor district sales manager together, it was awesome to hear the traveling. I realized that the Mini would reached record heights. We were with- Mike Ausman and product specialist differences. The guys all had fantastic make a truly great travel guitar. The out heat or electricity for four days, and Wayne Johnson]. We are both retired attitudes, great senses of humor, and a Road Show was on a Tuesday, and were banned from returning home for teachers and have hundreds if not wonderful dedication to Taylor Guitars. -

The Making of a Modern Fingerstyle Album: Exploring Relevant Techniques and Fingerstyle History

University of Huddersfield Repository Cronin, Reece The Making of a Modern Fingerstyle Album: Exploring Relevant Techniques and Fingerstyle History Original Citation Cronin, Reece (2018) The Making of a Modern Fingerstyle Album: Exploring Relevant Techniques and Fingerstyle History. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34632/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ The Making of a Modern Fingerstyle Album: Exploring Relevant Techniques and Fingerstyle History Reece Cronin A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music by Research The University of Huddersfield February