A Comparative Study on the Published Completions of the Unfinished Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annäherungen an Alma Mahler-Werfel (1)

Musikstunde „Sie war wie ein Vulkan!“ Annäherungen an Alma Mahler-Werfel (1) Von Susanne Herzog Sendung: 18. Februar 2019 Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: 2015 SWR2 können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.SWR2.de, auf Mobilgeräten in der SWR2 App, oder als Podcast nachhören: Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2- Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de Die neue SWR2 App für Android und iOS Hören Sie das SWR2 Programm, wann und wo Sie wollen. Jederzeit live oder zeitversetzt, online oder offline. Alle Sendung stehen sieben Tage lang zum Nachhören bereit. Nutzen Sie die neuen Funktionen der SWR2 App: abonnieren, offline hören, stöbern, meistgehört, Themenbereiche, Empfehlungen, Entdeckungen … Kostenlos herunterladen: www.swr2.de/app SWR2 Musikstunde mit Susanne Herzog 18. Februar – 23. Februar 2019 „Sie war wie ein Vulkan!“ Annäherungen an Alma Mahler-Werfel (1) Mit Susanne Herzog. „Sie war wie ein Vulkan“ hat Anna Mahler über ihre Mutter Alma Mahler-Werfel gesagt und ihre „Begeisterungsfähigkeit für alles Künstlerische“ betont. Den Facetten der schillernden Persönlichkeit von Alma Mahler-Werfel und ihren Beziehungen zu so vielen großen Künstlern des 20. Jahrhunderts ist die SWR 2 Musikstunde diese Woche auf der Spur. -

Schubert's Mature Operas: an Analytical Study

Durham E-Theses Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study Bruce, Richard Douglas How to cite: Bruce, Richard Douglas (2003) Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4050/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Richard Douglas Bruce Submitted for the Degree of PhD October 2003 University of Durham Department of Music A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without their prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. 2 3 JUN 2004 Richard Bruce - Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Submitted for the degree of Ph.D (2003) (Abstract) This thesis examines four of Franz Schubert's complete operas: Die Zwillingsbruder D.647, Alfonso und Estrella D.732, Die Verschworenen D.787, and Fierrabras D.796. -

FARA Second Semi-Annual Report

U.S. Department of Justice . Washington, D.C. 20530 Report of the Attorney General to the Congress of the United States on the Administration of the . Foreign Agents Registration Act . of 1938, as amended, for the six months ending December 31, 2014 Report of the Attorney General to the Congress of the United States on the Administration of the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended, for the six months ending December 31, 2014 LISTING ACCORDING TO THE GEOGRAPHICAL AREA OR NATIONALITY FIELD OF REGISTRANTS WHOSE STATEMENTS WERE IN ACTIVE STATUS AT ANY TIME DURING THIS SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT (T) Indicates registration terminated during this six month reporting period. (t) Indicates foreign principal terminated during the six month reporting period. The dollar figure included for each registrant represents the total amount of money received in the United States in furtherance of the agency purpose by agents working on behalf of the foreign principal. This information is based on the registrant’s reporting period rather than the calendar year. The list is compiled alphabetically by country or location1; however, it necessarily will include foreign principals which have no association with the government. The report sets forth the name, address and registration number of the registrant, the identity of the foreign principal, the nature of their activities, and the amount of monies received, if any. 1 Country or location is not reflective of United States foreign policy regarding recognition of sovereignty. AFGHANISTAN Fenton Communications -

Mayke Rademakers

Mayke Rademakers La Furia: Passion, Fury and Melancholia Enrique Granados | Joaquín Nin | Carlos Guastavino Gaspar Cassadó | Antón García Abril | Manuel de Falla Alberto Ginastera | Ástor Piazzolla Matthijs Verschoor - piano 1 Mayke Rademakers La Furia: Passion, Fury and Melancholia Enrique Granados | Joaquín Nin | Carlos Guastavino Gaspar Cassadó | Antón García Abril | Manuel de Falla Alberto Ginastera | Ástor Piazzolla Matthijs Verschoor - piano ENRIQUE GRANADOS (1867-1916) CARLOS GUASTAVINO (1912-2000) transcription by Mayke Rademakers [12] La Rosa y el Sauce 2:46 [1] Danza Española no. 5 – Andaluza 3:51 JOAQUÍN NIN (1879-1949) MANUEL DE FALLA (1876-1946) Seguida Española transcription by Maurice Maréchal [13] Vieja Castilla 1:58 Suite Popular Española [14] Murciana 1:35 [2] El paño moruno 2:08 [15] Asturiana 3:13 [3] Asturiana 2:27 [16] Andaluza 1:56 [4] Jota 3:02 [5] Nana 2:38 ÁSTOR PIAZZOLLA (1921-1992) [6] Canción 1:27 [17] Le Grand Tango 12:05 [7] Polo 1:33 ALBERTO GINASTERA (1916-1983) ANTÓN GARCÍA ABRIL (b. 1933) transcription by Pierre Fournier transcription by Mayke Rademakers [18] Triste 3:51 [8] No por Amor, no por Tristeza 3:26 GASPAR CASSADÓ (1897-1966) total time 64:07 Suite for Cello Solo [9] Preludio-Fantasia 6:15 [10] Sardana (Danza) 3:27 [11] Intermezzo e Danza Finale 6:20 4 5 Ruud Meijer talks with Mayke Rademakers “All my life, I’ve played a lot of Spanish music, and so has my partner and duo- more lyrical and uses a lot of embellishment, while De Falla is more primitive, pianist Matthijs Verschoor,” says Mayke Rademakers. -

Franz Schubert's Impromptus D. 899 and D. 935: An

FRANZ SCHUBERT’S IMPROMPTUS D. 899 AND D. 935: AN HISTORICAL AND STYLISTIC STUDY A doctoral document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2005 by Ina Ham M.M., Cleveland Institute of Music, 1999 M.M., Seoul National University, 1996 B.M., Seoul National University, 1994 Committee Chair: Dr. Melinda Boyd ABSTRACT The impromptu is one of the new genres that was conceived in the early nineteenth century. Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 are among the most important examples to define this new genre and to represent the composer’s piano writing style. Although his two sets of four impromptus have been favored in concerts by both the pianists and the audience, there has been a lack of comprehensive study of them as continuous sets. Since the tonal interdependence between the impromptus of each set suggests their cyclic aspects, Schubert’s impromptus need to be considered and be performed as continuous sets. The purpose of this document is to provide useful resources and performance guidelines to Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 by examining their historical and stylistic features. The document is organized into three chapters. The first chapter traces a brief history of the impromptu as a genre of piano music, including the impromptus by Jan Hugo Voŕišek as the first pieces in this genre. -

-

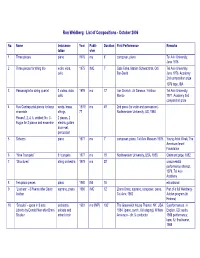

Ron Weidberg: List of Compositions - October 2006

Ron Weidberg: List of Compositions - October 2006 No. Name Instrumen- Year Publi- Duration First Performance Remarks tation sher 1 Three pieces piano 1975 ms 5' composer, piano Tel Aviv University, June 1976 2 Three pieces for string trio violin, viola, 1975 IMC 7’ Gabi Falka, Marian Schwarzbrat, Odi Tel Aviv University, cello Bar-David June 1976. Academy 2nd composition prize 1976 tape, IBA 3 Passacaglia for string quartet 2 violins, viola, 1976 ms 12' Ilan Gronich, Uri Samson, Ya'akov Tel Aviv University, cello Menze 1977. Academy 2nd composition prize 4 Five Contrapuntal pieces for large winds, brass, 1976/ ms 40' 2nd piece (for violin and percussion) - ensemble strings, 77 Northwestern University, US, 1980. Pieces1, 2, 4, 5, untitled; No. 3 - 2 pianos, 2 Fugue for 2 pianos and ensemble electric guitars drum-set, percussion 5 Scherzo piano 1977 ms 7' composer, piano, Tel Aviv Museum 1979. Young Artist Week, The American-Israel Foundation 6 “Nine Trumpets” 9 trumpets 1977 ms 15' Northwestern University, USA, 1980. Clairmont prize, 1982 7 “Structures” string orchestra 1978 ms 20' unsuccessful performance attempt, 1979, Tel Aviv Academy 8 Ten piano pieces piano 1980 IMI 15’ educational 9 “Lost war” - 3 Poems after David soprano, piano 1980 IMC 12’ Zimra Ornat, soprano, composer, piano, Part of a full Weidberg- Avidan Tel-Aviv, 1983 Avidan program (in Hebrew) 10 “Dracula” - opera in 3 acts. orchestra, 1981 ms (IMP) 100' The Greenwich House Theater, NY, USA, 5 performances. in Libretto by Donald Nier after Bram soloists and 1984. (piano, synth., full staging). William English. CD: audio, Stocker mixed choir Anderson - dir. -

Franz Schubert Written and Narrated by Jeremy Siepmann with Tom George As Schubert

LIFE AND WORKS Franz Schubert Written and narrated by Jeremy Siepmann with Tom George as Schubert 8.558135–38 Life and Works: Franz Schubert Preface If music is ‘about’ anything, it’s about life. No other medium can so quickly or more comprehensively lay bare the very soul of those who make or compose it. Biographies confined to the limitations of text are therefore at a serious disadvantage when it comes to the lives of composers. Only by combining verbal language with the music itself can one hope to achieve a fully rounded portrait. In the present series, the words of composers and their contemporaries are brought to life by distinguished actors in a narrative liberally spiced with musical illustrations. Unlike the standard audio portrait, the music is not used here simply for purposes of illustration within a basically narrative context. Thus we often hear very substantial chunks, and in several cases whole movements, which may be felt by some to ‘interrupt’ the story; but as its title implies the series is not just about the lives of the great composers, it is also an exploration of their works. Dismemberment of these for ‘theatrical’ effect would thus be almost sacrilegious! Likewise, the booklet is more than a complementary appendage and may be read independently, with no loss of interest or connection. Jeremy Siepmann 8.558135–38 3 Life and Works: Franz Schubert © AKG Portrait of Franz Schubert, watercolour, by Wilhelm August Rieder 8.558135–38 Life and Works: Franz Schubert Franz Schubert(1797-1828) Contents Page Track Lists 6 Cast 11 1 Historical Background: The Nineteenth Century 16 2 Schubert in His Time 26 3 The Major Works and Their Significance 41 4 A Graded Listening Plan 68 5 Recommended Reading 76 6 Personalities 82 7 A Calendar of Schubert’s Life 98 8 Glossary 132 The full spoken text can be found on the CD-ROM part of the discs and at: www.naxos.com/lifeandworks/schubert/spokentext 8.558135–38 5 Life and Works: Franz Schubert 1 Piano Quintet in A major (‘Trout’), D. -

Mahler's Symphony No. 10

SCHEDULE OF EVENTS WEDNESDAY, MAY 17, 7:30PM [Concert] Gordon Gamm Theater at The Dairy Center • G. Kurtág: Signs, Games, Messages (Jelek, Játékok és Üzenetek) • D. Matthews: Romanza for Violin and Piano, op 119a (U.S. Premiere) • G. Mahler/A. Schnittke: Piano Quartet in a (fragments) • F. Schubert: String Quintet in C, D. 956, Op. posth. 163 THURSDAY, MAY 18, 1:30PM [Master Class] Boulder Public Library • The Conducting Fellows, Kenneth Woods, David Matthews and Mahler specialists. • Mahler: Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen– Chamber version (Schoenberg) FRIDAY, MAY 19, 2:00PM [FILM] BOEDECKER THEATRE AT THE DAIRY CENTER, BOULDER • Ken Russell’s Mahler SATURDAY, MAY 20, [Symposium] (speaker order subject to change) • Morning Session – 8:30am – C-199 – Imig Building, CU Boulder • Frans Bouwman ”Transcribing Mahler 10: what does it show?” • David Matthews ”Mahler’s 10th Symphony – Restored to Life” • Kenneth Woods, Artistic Director and Conductor, Colorado MahlerFest “A Conductor’s Perspective on the Tenth Symphony” • Jerry Bruck assisted by Louise Bloomfield In“ Search of Mahler: A Personal Recollection” • Lunch – Atrium Lobby, ATLAS building, University of Colorado • Afternoon Session – 1:30pm - Rm 102 – ATLAS Building, CU Boulder • Panel Discussion with David Matthews, Kenneth Woods and Donald Fraser • Jason Starr’s “For the Love of Mahler – The Inspired Life of Henry-Louis de La Grange” Presented in Memory of Henry-Louis de La Grange SATURDAY, MAY 20, 7:30 PM [Orchestral Concert] Macky Auditorium, University of Colorado SUNDAY, MAY 21, 3:30 PM [Orchestral Concert] Macky Auditorium, University of Colorado • Sir Edward Elgar (arr. David Matthews): String Quartet in e, opus 83 – arranged for string orchestra (2010) (US Premiere) • Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. -

Rondo Form.Pdf

11/19/2008 The Classical Rondo The classical rondo features a recurring refrain called the rondo theme (or the principal theme), separated by digressions called episodes The classical rondo is a light and spritely type of piece with a tuneful and easily recognizable rondo theme It is often found as the final movement in symphonies, Rondo Form sonatas, string quartets and concertos The Rondo Theme The Episodes The rondo theme is always stated in the tonic key The episodes usually contrast with the rondo theme, whenever it returns although they may use similar motives The phrase structure of the rondo theme is usually quite The episodes are often in closely related keys—for clear, with regular phrase lengths forming a harmonically example, the first episode tends to be in the dominant closed period key or the relative major Sometimes when the rondo theme is repeated, it is varied The episodes may either be thematic (presenting their slightly—this is done to prevent monotony own contrasting themes) or developmental (developing motives from the rondo theme in several keys) Often, the rondo theme is shortened when it returns The main parts of the rondo are sometimes connected by short transitions and the rondo as a whole is often followed by a coda Five- and Seven-Part Rondos Sonata-Rondo Form The most common rondo types are five-part (A B A C A) Sonata-Rondo form is an interesting combination of sonata or (A B A B’ A) and seven-part (A B A C A B’ A)—with A form and rondo form representing the recurring rondo theme It is essentially -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

OS COMPOSITORES E SEU TEMPO Normando Carneiro

Normando Carneiro OS COMPOSITORES E SEU TEMPO Normando Carneiro Natal 2018 1 Os Compositores de seu tempo Normando Carneiro Vivaldi, Antonio (1678-1741) Compositor e violinista italiano, o mais influente de sua época. Nasceu em 04/03/1678 em Veneza, estudou com seu pai, violinista na catedral de San Marcos. Ordenou-se sacerdote em 1703, chamavam-no interprete russo (o cura ruivo), e começou a ensinar no Ospedale della Pietá que era um estabelecimento para meninas órfãs. Trabalhou ali como diretor musical até 1740, como professor e compunha concertos e oratórios para os concertos semanais através dos que conseguiu uma fama internacional. A partir de 1713 Vivaldi também trabalhou como compositor e empresário de óperas em Veneza e viajava a Roma, Mantua e outras cidades para supervisionar as representações de suas óperas. Para 1740 entrou ao serviço do corte do imperador Carlos VI em Viena. Faleceu nesta cidade o 28 de julho de 1741. Composições Vivaldi escreveu mais de 500 concertos e 70 sonatas, 45 óperas, música religiosa como o oratório Judithatriumphans (1716), a Glória em re (1708), missas e motetes. Suas sonatas instrumentais são mais conservadoras que seus concertos e sua música religiosa com frequencia reflete o estilo operístico da época e a alternância de orquestra e solistas que ajudou a introduzir nos concertos. Johann SebastianBach, contemporâneo seu, embora algo mais jovem, estudou a obra de Vivaldi em seus anos de formação e de alguns dos concertos para violino e sonatas de Vivaldi só existem as transcrições (em sua maior parte para clavecín) de Bach. 2 Os Compositores de seu tempo Normando Carneiro Johann Sebastian Bach (Eisenach, 21/03/1685 — Leipzig, 28/07/1750) Compositor, cravista, Kapellmeister, regente, organista, professor violinista e violista oriundo do Sacro Império Romano-Germânico, atual Alemanha.