Download Chapter In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2013

Produced by volunteers for the people of Sedgefield, Bradbury, Mordon & Fishburn Published by Sedgefield Development Trust: Company No 4312745 Charity No 1100906 SedgefieldNEWS Text/call 07572 502 904 : email [email protected] September 2013 STOP PRESS SATURDAY 31st AUGUST Mordon on the Green Table Top Sale will be in the Hall if the weather is unkind. 10am - 12 noon. Come along, bring your friends and be assured of a warm welcome. APOLOGY Sedgefield Smilers Last month we brought you news of the planned walking weekend to the Peak District in April 2014, but unfortunately the contact details were missed out. We do apologise for this. The weekend is open to members and non members of the walking group. If you are interested, please contact Suzanne on 01429 882250 for more details. Below: A very special visitor to Bradbury is captured on camera by John Burrows. Gemma Hill, Victoria Sirrell & Harriet Wall about to embark on their trip A Jamboree for three (plus another thousand or so!) Three Sedgefield Guides had a once in a lifetime opportunity this summer, to represent village and country at an International Jamboree. Gemma, Victoria and Harriet, from 1st Sedgefield Guides, joined around 20 guides from County Durham and Darlington (the “North East Ninjas” - what would Baden-Powell think!) at the 10 day JamBe 2013 event, which took place in woodlands near the town of Leuven in Belgium. There they met around 1200 Scouts and Guides from all over the world to take part in a activities which ranged from sports to crafts, outdoor skills to international friendship. -

Durham Rare Plant Register 2011 Covering VC66 and the Teesdale Part of VC65

Durham Rare Plant Register 2011 Covering VC66 and the Teesdale part of VC65 JOHN L. DURKIN MSc. MIEEM BSBI Recorder for County Durham 25 May Avenue. Winlaton Mill, Blaydon, NE21 6SF [email protected] Contents Introduction to the rare plants register Notes on plant distribution and protection The individual species accounts in alphabetical order Site Index First published 2010. This is the 2011, second edition. Improvements in the 2011 edition include- An additional 10% records, most of these more recent and more precise. One kilometre resolution maps for upland and coastal species. My thanks to Bob Ellis for advice on mapping. The ―County Scarce‖ species are now incorporated into the main text. Hieracium is now included. This edition is ―regionally aligned‖, that is, several species which are county rare in Northumberland, but were narrowly rejected for the Durham first edition, are now included. There is now a site index. Cover picture—Dark Red Helleborine at Bishop Middleham Quarry, its premier British site. Introduction Many counties are in the process of compiling a County Rare Plant Register, to assist in the study and conservation of their rare species. The process is made easier if the county has a published Flora and a strong Biological Records Centre, and Durham is fortunate to have Gordon Graham's Flora and the Durham Wildlife Trust‘s ―Recorder" system. We also have a Biodiversity project, based at Rainton Meadows, to carry out conservation projects to protect the rare species. The purpose of this document is to introduce the Rare Plant Register and to give an account of the information that it holds, and the species to be included. -

Durham Dales Map

Durham Dales Map Boundary of North Pennines A68 Area of Outstanding Natural Barleyhill Derwent Reservoir Newcastle Airport Beauty Shotley northumberland To Hexham Pennine Way Pow Hill BridgeConsett Country Park Weardale Way Blanchland Edmundbyers A692 Teesdale Way Castleside A691 Templetown C2C (Sea to Sea) Cycle Route Lanchester Muggleswick W2W (Walney to Wear) Cycle Killhope, C2C Cycle Route B6278 Route The North of Vale of Weardale Railway England Lead Allenheads Rookhope Waskerley Reservoir A68 Mining Museum Roads A689 HedleyhopeDurham Fell weardale Rivers To M6 Penrith The Durham North Nature Reserve Dales Centre Pennines Durham City Places of Interest Cowshill Weardale Way Tunstall AONB To A690 Durham City Place Names Wearhead Ireshopeburn Stanhope Reservoir Burnhope Reservoir Tow Law A690 Visitor Information Points Westgate Wolsingham Durham Weardale Museum Eastgate A689 Train S St. John’s Frosterley & High House Chapel Chapel Crook B6277 north pennines area of outstanding natural beauty Durham Dales Willington Fir Tree Langdon Beck Ettersgill Redford Cow Green Reservoir teesdale Hamsterley Forest in Teesdale Forest High Force A68 B6278 Hamsterley Cauldron Snout Gibson’s Cave BishopAuckland Teesdale Way NewbigginBowlees Visitor Centre Witton-le-Wear AucklandCastle Low Force Pennine Moor House Woodland ButterknowleWest Auckland Way National Nature Lynesack B6282 Reserve Eggleston Hall Evenwood Middleton-in-Teesdale Gardens Cockfield Fell Mickleton A688 W2W Cycle Route Grassholme Reservoir Raby Castle A68 Romaldkirk B6279 Grassholme Selset Reservoir Staindrop Ingleton tees Hannah’s The B6276 Hury Hury Reservoir Bowes Meadow Streatlam Headlam valley Cotherstone Museum cumbria North Balderhead Stainton RiverGainford Tees Lartington Stainmore Reservoir Blackton A67 Reservoir Barnard Castle Darlington A67 Egglestone Abbey Thorpe Farm Centre Bowes Castle A66 Greta Bridge To A1 Scotch Corner A688 Rokeby To Brough Contains Ordnance Survey Data © Crown copyright and database right 2015. -

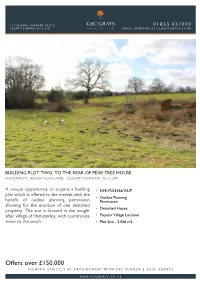

Offers Over £150,000 Viewing Strictly by Appointment with the Vendor’S Sole Agents

12 THE BANK, BARNARD CASTLE, 01833 637000 COUNTY DURHAM, DL12 8PQ EMAIL: [email protected] BUILDING PLOT TWO, TO THE REAR OF PEAR TREE HOUSE HAMSTERLEY, BISHOP AUCKLAND, COUNTY DURHAM, DL13 3PP A unique opportunity to acquire a building • DM/17/03336/OUT plot which is offered to the market with the • Outline Planning benefit of outline planning permission Permission allowing for the erection of one detached • Detached House property. The site is located in the sought after village of Hamsterley, with countryside • Popular Village Location views to the south. • Plot Size - 2,056 m2 Offers over £150,000 VIEWING STRICTLY BY APPOINTMENT WITH THE VENDOR’S SOLE AGENTS WWW. GSCGRAYS. CO. UK BUILDING PLOT TWO, TO THE REAR OF PEAR TREE HOUSE HAMSTERLEY, BISHOP AUCKLAND, COUNTY DURHAM, DL13 3PP SITUATION & AMENITIES AREAS, MEASUREMENTS & OTHER Wolsingham 6 miles, Bishop Auckland 7 miles, INFORMATION Barnard Castle 12 miles, Durham 19 miles, Darlington All areas, measurements and other information have 19 miles, Newcastle 32 miles. Please note all distances been taken from various records and are believed to are approximate. State secondary school with sixth be correct but any intending purchaser(s) should not form at Wolsingham. Local private education in rely on them as statements of fact and should satisfy Durham and Barnard Castle. Theatres at Darlington themselves as to their accuracy. The vendors reserve and Durham. Golf at Bishop Auckland, Barnard the right to change and amend the boundaries. Castle, Darlington and Durham. The plot is situated SERVICES in the picturesque, rural village of Hamsterley, which No services to site. -

Chapter.Org of Our Wonderful Community Email: [email protected] School Celebrates 50Th Volunteers Needed Anniversary with Top Award for New Food Bank

Published at: Friday 30th May 2014 First Floor, Town Council Offices, Issue 677 Civic Hall Square, Shildon, TER DL4 1AH. AP Telephone/Fax: 01388 775896 hill Duty journalist: 0790 999 2731 Ferry H ilt o n C & C h At the heart www.thechapter.org of our wonderful community email: [email protected] School celebrates 50th Volunteers needed anniversary with top award for new food bank Chiton Town Council are unknown where it will looking into setting up a based or when it would new foodbank after the be set up or start running. need for one was raised Vicky Nelson, clerical by the Citizens Advice officer at Chilton Town Bureau. Council said, “The Town In the UK there are an in- Council could not run the creasing number of people service but are looking going hungry everyday for for volunteers who could reasons ranging from re- operate the service and dundancy to receiving an hand out the food. We unexpected bill, or simply have a list of nine people by being on a low income. so far but we would like Along with rising costs of to enlist a few more”. food and fuel, combined Currently the nearest with static income, foodbank to Chilton is at high unemployment and St. Luke’s Church in Fer- changes to benefits, ryhill. people are finding them- For further information, selves in crisis. or to express an interest The scheme is still in the as a volunteer, call into early stages of planning Chilton Town Council or Pupils from Ferryhill Business and Enterprise College with their Outstanding Achieve- and it is currently telephone 01388 721788. -

THE RURAL ECONOMY of NORTH EAST of ENGLAND M Whitby Et Al

THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND M Whitby et al Centre for Rural Economy Research Report THE RURAL ECONOMY OF NORTH EAST ENGLAND Martin Whitby, Alan Townsend1 Matthew Gorton and David Parsisson With additional contributions by Mike Coombes2, David Charles2 and Paul Benneworth2 Edited by Philip Lowe December 1999 1 Department of Geography, University of Durham 2 Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies, University of Newcastle upon Tyne Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Scope of the Study 1 1.2 The Regional Context 3 1.3 The Shape of the Report 8 2. THE NATURAL RESOURCES OF THE REGION 2.1 Land 9 2.2 Water Resources 11 2.3 Environment and Heritage 11 3. THE RURAL WORKFORCE 3.1 Long Term Trends in Employment 13 3.2 Recent Employment Trends 15 3.3 The Pattern of Labour Supply 18 3.4 Aggregate Output per Head 23 4 SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL DYNAMICS 4.1 Distribution of Employment by Gender and Employment Status 25 4.2 Differential Trends in the Remoter Areas and the Coalfield Districts 28 4.3 Commuting Patterns in the North East 29 5 BUSINESS PERFORMANCE AND INFRASTRUCTURE 5.1 Formation and Turnover of Firms 39 5.2 Inward investment 44 5.3 Business Development and Support 46 5.4 Developing infrastructure 49 5.5 Skills Gaps 53 6. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 55 References Appendices 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The scope of the study This report is on the rural economy of the North East of England1. It seeks to establish the major trends in rural employment and the pattern of labour supply. -

Stanhope Churchyard

The Weardale Churchyard Project Prepared by Margaret Manchester on behalf of Weardale Field Study Society St Thomas' Churchyard, Stanhope, Weardale, Co.Durham, England. MEM NO. INSCRIPTION 1 In Affectionate Remembrance/ of/ GEORGE SANDERSON/ BELOVED HUSBAND OF HANNAH SANDERSON/ WHO DIED APRIL 4TH 1881 AGED 54 YEARS/ ALSO CLYDE SON OF THE ABOVE/ DIED MARCH 9TH 1870 AGED 2 YEARS/ ALSO WILLIAM SON OF THE ABOVE/ DIED AUGUST 9TH 1881 AGED 37 YEARS/ ALSO JOHN GEORGE SON OF THE ABOVE/ DIED JANY 20TH 1885 AGED 33 YEARS/ ALSO THOMAS SANDERSON/ WHO DIED JUNE 7TH 1887/ AGED 39 YEARS/ ALSO ROBERT SANDERSON/ WHO DIED MAY 22ND 1888/ AGED 34 YEARS/ ALSO OF THE ABOVE HANNAH SANDERSON/ DIED APRIL 3RD 1902 AGED 74 YEARS/ ALSO OF ANNIE NICHOLSON/ DIED APRIL 26TH 1906 AGED 34 YEARS 2 In/ MEMORY OF/ HANNAH WIFE OF/ JOSEPH DIXON OF EASTGATE/ WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE/ FEB 21ST 1860 AGED 73 YEARS/ ALSO OF ANN THEIR THIRD/ DAUGHTER WHO DIED/ JULY 1ST 1821 AGED 7 YEARS/ ALSO OF THE ABOVE/ JOSEPH DIXON WHO DIED/ DECEMBER 24TH 1861 AGED 74 YEARS 3 In Loving Memory/ of/ NICHOLAS/ BELOVED HUSBAND/ OF ELIZABETH SANDERSON/ WHO DIED DECR 5TH 1885/ AGED 67 YEARS./ ALSO OF THEIR CHILDREN/ JOHN/ DIED JUNE 3RD 1864 AGED 21 YEARS/ SARAH/ DIED NOVR 10TH 1866 AGED 20 YEARS/ MARY/ DIED DECR 7TH 1882 AGED 23 YEARS/ AND ELIZABETH HIS BELOVED WIFE/ WHO DIED OCT 2ND 1892/ AGED 73 YEARS/ "THY WILL BE DONE"/ ANNIE SMOKER/ DIED NOV 21ST 1927/ AGED 87 YEARS/ FREDERICK SMOKER/ DIED MARCH 9TH 1932/ AGED 83 YEARS 4 In/ Loving Memory of/ Thomas WILSON/ OF SCURFIELD HOUSE/ WHO DIED 25 DEC 1843/ AGED 46 YEARS./ ALSO OF JANE, WIFE OF THE ABOVE/ WHO DIED 26 APRIL 1892,/ AGED 94 YEARS./ ALSO OF/ ISABELLA, THEIR DAUGHTER/ WHO DIED AT BISHOP OAK/ 26 DEC 1902/ AGED 73 YEARS./ ALSO OF ELIZABETH, THEIR DAUGHTER/ WHO DIED AT EAST BIGGINS/ 20 JULY 1908,/ AGED 81 YEARS. -

North Pennines AONB High Nature Value Farming Research

North Pennines AONB High Nature Value Farming Research A report for the North Pennines AONB partnership European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism and Cumulus Consultants Ltd. Mike Quinn, Creative Commons Licence North Pennines AONB High Nature Value Farming Research A report for the North Pennines AONB partnership European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism and Cumulus Consultants Ltd. December 2013 Report prepared by: Gwyn Jones, EFNCP Paul Silcock, CC Jonathan Brunyee, CC Jeni Pring, CC This report was commissioned by the North Pennines AONB Partnership. Its content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the funders. Thanks to Karen MacRae for proof reading, but all mistakes are the authors’. Thanks also to Rebecca Barrett for her enthusiasm and support and to Pat Thompson for help with bird data. European Forum on Nature Conservation and Cumulus Consultants Ltd, Pastoralism, The Palmers, Wormington Grange, 5/8 Ellishadder, Culnancnoc, Wormington, Broadway, Portree IV51 9JE Worcestershire. WR12 7NJ Telephone: +44 (0)788 411 6048 Telephone: +44 (0)1386 584950 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Internet: www.efncp.org Internet: www.cumulus-consultants.co.uk 2 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. -

County Durham Plan (Adopted 2020)

County Durham Plan ADOPTED 2020 Contents Foreword 5 1 Introduction 7 Neighbourhood Plans 7 Assessing Impacts 8 Duty to Cooperate: Cross-Boundary Issues 9 County Durham Plan Key Diagram and Monitoring 10 2 What the County Durham Plan is Seeking to Achieve 11 3 Vision and Objectives 14 Delivering Sustainable Development 18 4 How Much Development and Where 20 Quantity of Development (How Much) 20 Spatial Distribution of Development (Where) 29 5 Core Principles 71 Building a Strong Competitive Economy 71 Ensuring the Vitality of Town Centres 78 Supporting a Prosperous Rural Economy 85 Delivering a Wide Choice of High Quality Homes 98 Protecting Green Belt Land 124 Sustainable Transport 127 Supporting High Quality Infrastructure 138 Requiring Good Design 150 Promoting Healthy Communities 158 Meeting the Challenge of Climate Change, Flooding and Coastal Change 167 Conserving and Enhancing the Natural and Historic Environment 185 Minerals and Waste 212 Appendices A Strategic Policies 259 B Table of Superseded Policies 261 C Coal Mining Risk Assessments, Minerals Assessments and Minerals and/or Waste 262 Infrastructure Assessment D Safeguarding Mineral Resources and Safeguarded Minerals and Waste Sites 270 E Glossary of Terms 279 CDP Adopted Version 2020 Contents List of County Durham Plan Policies Policy 1 Quantity of New Development 20 Policy 2 Employment Land 30 Policy 3 Aykley Heads 38 Policy 4 Housing Allocations 47 Policy 5 Durham City's Sustainable Urban Extensions 61 Policy 6 Development on Unallocated Sites 68 Policy 7 Visitor Attractions -

1 STANHOPE PARISH COUNCIL at a Meeting of the Council Held in the Dales Centre, Stanhope on 5Th February 2020 PRESENT: Cllr D Cr

STANHOPE PARISH COUNCIL At a meeting of the Council held in the Dales Centre, Stanhope on 5th February 2020 PRESENT: Cllr D Craig Chairman Cllr L Blackett, Cllr M Brewin, Cllr Mrs H Maddison, Cllr Mrs A Humble, Cllr W Wearmouth Cllr B Thompson, Cllr D Ellwood, Cllr Mrs S Thompson, Cllr Mrs D Sutcliff, Cllr Miss F Graham, Cllr Miss J Carrick, Cllr Mrs A Hawkes S Anderson Clerk ALSO PRESENT: Tri-responder Jamie Clarkson County Councillor Mrs A Savory 10180 Apologies for Absence All councillors present 10181 To receive any declarations of Interest from Members Cllr Wearmouth page 2 Scottish Woodlands 4th Dec 2019 if mentioned 10182 Minutes of the meeting held on 4th December 2019 Minutes were moved as a true and correct record and were signed by the Chairman 10183 Police and the Community Cllr Craig welcomed J Clarkson to the meeting who read the stats from 1st Jan. There were no thefts and one vehicle crime where a quad bike was stolen and the day after two cars were set alight. Anti Social behaviour had been reported at Garden Close, Stanhope. There has been a problem with off road vehicles at St Johns Chapel and drones will be used soon. Concerns were raised about the thefts of recent quad bikes and the lack of police protection in the dale. Arrests have been made with recent poaching in Rookhope and residents are encouraged to ring the police. Young Heros need nominations and in July an event will be held. Rural Watch is going out soon and vehicles will be stopped. -

BEDBURN COTTAGES Bedburn, County Durham

BEDBURN COTTAGES Bedburn, County Durham BEDBURN COTTAGES BEDBURN, HAMSTERLEY, COUNTY DURHAM, DL13 3NW Hamsterley 1⁄2 mile, Bishop Auckland 8 miles, Durham 16 miles, Darlington 17 miles A BEAUTIFULLY POSITIONED, STONE-BUILT FAMILY HOUSE OPPOSITE A MILL POND WITH A LARGE GARDEN AND ADDITIONAL WOODLAND. Accommodation Reception Hallway • Study • Cloakroom • Sitting Room • Dining Room Snug/Library • Kitchen/Breakfast Room and Utility Room • Main bedroom with ensuite bathroom • 4 further bedrooms and family bathroom Large double garage with planning consent for conversion to 2 bedroomed annexe. Delightful, fully enclosed garden (dog proof). Adjoining amenity woodland. In all about 2.74 acres (1.1 ha) FOR SALE AS A WHOLE OR IN TWO LOTS 5 & 6 Bailey Court, Colburn Business Park, North Yorkshire, DL9 4QL Tel: 01748 897610 www.gscgrays.co.uk [email protected] Offices also at: Alnwick Barnard Castle Chester-le-Street Easingwold Hamsterley Lambton Estate Leyburn Stokesley Tel: 01665 568310 Tel: 01833 637000 Tel: 0191 303 9540 Tel: 01347 837100 Tel: 01388 487000 Tel: 0191 385 2435 Tel: 01969 600120 Tel: 01642 710742 Situation and Amenities Bedburn Cottages Bedburn Cottage lies on the edge of the quiet hamlet of Bedburn about 1⁄2 a mile from Bringing together two homes has provided light and spacious rooms, and in particular on the the village of Hamsterley and close to Hamsterley Forest. The house is on the lane with its ground floor. The reception hall leads into a good sized, comfortable study with a cloakroom gardens and woodland behind and looks out over a delightful mill pond and into the forest in a and wc off with marble floor and surfaces. -

WVN 2014 Emap.Indd

© The Weardale Museum The Weardale Railway © Cube Creative Group © Forestry Commission Picture Library - J. McFarlane © Killhope Leadmining Museum © Forestry Commission Picture Library - Mark Pinder - Hamsterley Forest A Warm Weardale Welcome Weardale The area’s rich industrial heritage can be seen in the Lying high in the North Pennines, Weardale is a twenty remains of our lead mining past, and you can see Congratulations mile ribbon of river and road bringing you along tranquil how the miners lived and worked on a visit to family- Where we are & lanes, past tumbling rivers and waterfalls, through friendly Killhope, the North of England Lead Mining vibrant communities, over high moorland expanses Museum. Don’t forget to stop off at the fascinating how to get here You’ve found us! and within touching distance of the rarest wildlife, all Weardale Museum in Ireshopeburn, where you can through a landscape forged by man’s centuries’ old see the Weardale Tapestry and marvel at the historic battles with nature. High House Chapel. By road: Weardale is in the North Pennines Now get to know us with the A1M to the eastern side and the A great place to fi nd out about the area is the Durham A great way to get to grips with the rural way of life M6 to the west. Appropriate feeder roads Dales Centre in Stanhope – with its tearooms, gift and is to join the locals at one of the many agricultural lead into Weardale. craft shops it’s perfect for a leisurely afternoon; or 10 shows in August and September.