The First World War: and Its Aftermaths in the Seychelles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Axis and Allied Maritime Operations Around Southern Africa, 1939-1945

THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA, 1939-1945 Evert Philippus Kleynhans Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Military Science (Military History) in the Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof I.J. van der Waag Co-supervisor: Dr E.K. Fedorowich December 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: December 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract The majority of academic and popular studies on the South African participation in the Second World War historically focus on the military operations of the Union Defence Force in East Africa, North Africa, Madagascar and Italy. Recently, there has been a renewed drive to study the South African participation from a more general war and society approach. The South African home front during the war, and in particular the Axis and Allied maritime war waged off the southern African coast, has, however, received scant historical attention from professional and amateur historians alike. The historical interrelated aspects of maritime insecurity evident in southern Africa during the war are largely cast aside by contemporary academics engaging with issues of maritime strategy and insecurity in southern Africa. -

Xref Ml Catalogue for Auction 2

Online Auction 2 Page:1 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Other Pre-Decimals Lot 326 326 PB 1958 War Memorial 5½d+5½d setenant die proof in the issued colour ACSC 341-2DP(1) removed from the presentation mount, large margins except at L/R where cut close, light adhesive-stains at left & right, Cat $4000. 500 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - British Commonwealth Occupation Forces (B.C.O.F.) Lot 342 342 CB 1945 airmail cover with naval crest in green at U/L to GB with KGVI 3d purple-brown x3 tied by the woodcut 'TOKYO BAY/JAPAN' cancel with 'HMAS SHROPSHIRE/Official Signing of/Japanese Surrender' cachet in red and British 'POST/OFFICE - MARITIME/MAIL' machine in red, opened-out & minor blemishes. Unusual usage. 60 Ex Lot 343 343 VA 1946-48 Overprints ½d to 5/- Robes Thin Paper (unusually well centred) tied to plain cover by 'AUST ARMY PO/12OC48/214.' cds, Cat £275. (7) 200T Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au 10 - 12 October 2020 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - British Commonwealth Occupation Forces (B.C.O.F.) (continued) Lot Type Grading Description Est $A Lot 344 344 CO B 1949 airmail cover (230x168mm) to London with rare franking of unoverprinted 3d 1/- Lyrebird & Robes Thin Paper 5/- strips of 3 (Cat $750 for a single on cover) tied by 'AUST ARMY PO/11JE49/214' cds in use at Empire House in Tokyo, vertical fold & minor blemishes. A very scarce franking in any circumstances, all the more desirable for being a BCOF in Japan usage. -

The Naturalist and His 'Beautiful Islands'

The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific David Russell Lawrence The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific David Russell Lawrence Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Lawrence, David (David Russell), author. Title: The naturalist and his ‘beautiful islands’ : Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific / David Russell Lawrence. ISBN: 9781925022032 (paperback) 9781925022025 (ebook) Subjects: Woodford, C. M., 1852-1927. Great Britain. Colonial Office--Officials and employees--Biography. Ethnology--Solomon Islands. Natural history--Solomon Islands. Colonial administrators--Solomon Islands--Biography. Solomon Islands--Description and travel. Dewey Number: 577.099593 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: Woodford and men at Aola on return from Natalava (PMBPhoto56-021; Woodford 1890: 144). Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgments . xi Note on the text . xiii Introduction . 1 1 . Charles Morris Woodford: Early life and education . 9 2. Pacific journeys . 25 3 . Commerce, trade and labour . 35 4 . A naturalist in the Solomon Islands . 63 5 . Liberalism, Imperialism and colonial expansion . 139 6 . The British Solomon Islands Protectorate: Colonialism without capital . 169 7 . Expansion of the Protectorate 1898–1900 . -

September 2014

Listening POSTSEPT 2014 Vol 37 - No 4 THE CENTENNIAL EDITIONS 2014-18 ANZAC lighthouse legend grows Story page 26 The Official Journal of The Returned & Services League of Australia WA Branch Incorporated 2 The Listening Post SEPT 2014 State Executive contents 2011-2015 3 Life on the ANZAC convoy State President 4 Diary of Fred White Mr Graham Edwards AM 5 From the President’s Pen State Vice President Mr Denis Connelly 6 Your letters State Treasurer contact: 7 Bits & Pieces Mr Phillip Draber RFD JP Editorial and Advertising 8 Anyone for a brew? State Executive Information Mr Bob Allen OAM, Mr Scott Rogers Acting Editor: Amy Hunt 9287 3700 10 Poppies link to a mother’s love Mrs Judy Bland Mr Peter Aspinall Email: [email protected] 17 Women’s Forum Mr Gavin Briggs Mr Ross Davies Media & Marketing Manager: Mr Bill Collidge RFD Mr Tony Fletcher John Arthur 0411 554 480 19 Vietnam Veterans’ Day Mr David Elson BM Mrs Donna Prytulak Email: [email protected] 21 Albany ANZAC Centenary Mr John McCourt Graphic Design: Type Express Pages Trustees Printer: Rural Press 27 Albany’s sailing disaster Mr Don Blair OAM RFD ED Mr Kevin Trent OAM RFD JP Contact Details 29 WA’s ANZACs depart Mr Wayne Tarr RFD ED The Returned & Services League of Australia - WA Branch Incorporated 30 Goldfi elds honours 187 ANZAC House, 28 St Georges Tce 34 Sub Branch News Deadline for next PERTH WA 6000 PO Box 3023, EAST PERTH WA 6892 37 Anne Leach - Red Cross icon edition: Nov 17, 2014 Email: [email protected] 38 Sculptors’ iconic designs If possible, submissions should be typed Website: www.rslwahq.org.au and double-spaced. -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 30 June

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 30 June Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Jun 16 1832 – Native Americans: Battle of Burr Oak Grove » The Battle is either of two minor battles, or skirmishes, fought during the Black Hawk War in U.S. state of Illinois, in present-day Stephenson County at and near Kellogg's Grove. In the first skirmish, also known as the Battle of Burr Oak Grove, on 16 JUN, Illinois militia forces fought against a band of at least 80 Native Americans. During the battle three militia men under the command of Adam W. Snyder were killed in action. The second battle occurred nine days later when a larger Sauk and Fox band, under the command of Black Hawk, attacked Major John Dement's detachment and killed five militia men. The second battle is known for playing a role in Abraham Lincoln's short career in the Illinois militia. He was part of a relief company sent to the grove on 26 JUN and he helped bury the dead. He made a statement about the incident years later which was recollected in Carl Sandburg's writing, among others. Sources conflict about who actually won the battle; it has been called a "rout" for both sides. The battle was the last on Illinois soil during the Black Hawk War. Jun 16 1861 – Civil War: Battle of Secessionville » A Union attempt to capture Charleston, South Carolina, is thwarted when the Confederates turn back an attack at Secessionville, just south of the city on James Island. -

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 6 IUCN - The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biologi- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna cal diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- of fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their vation of species or biological diversity. conservation, and for the management of other species of conservation con- cern. Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: sub-species and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintaining biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of bio- vulnerable species. logical diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conservation Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitoring 1. To participate in the further development, promotion and implementation the status of species and populations of conservation concern. of the World Conservation Strategy; to advise on the development of IUCN's Conservation Programme; to support the implementation of the • development and review of conservation action plans and priorities Programme' and to assist in the development, screening, and monitoring for species and their populations. -

Perang Parit). Atau the Great War (Perang Besar

WW I - Part 1 Kita refresh laa pasai WWI ni. Perang ni juga dikenali dgn nama Trench War (Perang Parit). atau The Great War (Perang Besar). Dalam perang nilah...Jentera2 digunakan secara besar2an. Sebelum ni alat2 pengangkutan dijana oleh kuda (tupasal lah skarang ni pun kalau nak tgk kuasa enjin..depa mesti ckp kuasa kuda). Lori2, kereta kebal, pesawat dan kapal2 keluli yg diberi nama Dreadnought (pioneered oleh British pada 1906), kapalselam2 digunakan dgn meluas oleh kedua2 pihak yg bermusuhan. Kira macam..perang moden yg pertama laa. Teknoloji tentera mmg berkembang dlm perang ni. Perang ni menjadi amat sengit adalah kerana kekuatan kedua2 pihak yg bermusuhan adalah seimbang. Masing2 mempunyai teknoloji.... Bukan macam Italy lawan Ethiopia (Abyssinia) masa WWII yg kita cite lepas....sorang pakai tank dan sorang pakai lembing. Tak fair langsung...aaa perang yg ni adalah sebaliknya. Pernah satu ketika antara parit 1 (askar A) dan parit 2 (askar , Jarak cuma 500-700 mter je. hari ni askar A tawan parit 2, dua tiga hari besok, askar B pulak tawan parit 1..berlanjutan tawan menawan antara parit A dan B berbulan2 lamanya dan angka kematian berpuluh2 ribu. Memang seksa...askar biasalaa yg seksa..Jeneral2 kalau kita tgk...hanya memberi arahan saja dlm HQ yg serba mewah. Zaman ni masih dikira zaman ala2 Imperial. Manakan tidak, Negara2 yg terlibat mempunyai empayar dan masih berpaksikan King atau Queen. Apasal perang ni dipanggil Perang Dunia (World War I) ? Perang kat Eropah aje? WWI - Part 2 Sebelum kita pegi lebih jauh, cuba kita tgk keadaan Eropah sebelum meledaknya conflict gila khinzir ni. -

My Reminiscences of East Africa

My 'Reminiscences of East Africa .J General VOII Lettow-Vorbeck. [f'runJi:spiect. :My nEMINISCENCES I OF EAST AFRICA :: CJ3y General von Leitoto- Vorbeck With Portrait. 22 Maps and Sketch.Maps. and 13 Vraw;ngs 13y General von Lettoui- Vorbechs Adjutant LONDON: HURST AND BLACKETT. LTD. PATERNOSTER HOUSE, E.C. f I I I I ,.\ I PREFACE N all the German colon.ies,t~ough but a few d~ca~es old, a life I full of promise was discerruble. \Ve were beginning to under• stand the national value of our colonial possessions; settlers and capital were venturing in; industries and factories were beginning to flourish. Compared with that of other nations, the colonizing process of Germany had progressed peacefully and steadily, and the inhabitants had confidence in the justice of German administration. This development had barely commenced when it was destroyed by the world war. In spite of all tangible proofs to the contrary, an unjustifiable campaign of falsehood is being conducted in order to make the world believe that the Germans lacked colonizing talent and were cruel to the natives. A small force, mainly composed of these very natives, opposed this development. Almost without any external means of coercion, even without immediate payment, this force, with its numerous native followers, faithfully followed its German leaders throughout the whole of the prolonged war against a more than hundredfold superiority. When the armistice came it was still fit to fight, and imbued with the best soldierly spirit. That is a fact which cannot be controverted, and is in itself a sufficient answer to the hostile mis-statements. -

Australian Submarines from 1914 Africa's Indian Ocean Navies: Naval

ISSUE 152 JUNE 2014 Australian Submarines from 1914 Africa’s Indian Ocean Navies: Naval evolution in a complex and volatile region The Aussie military history your kids aren’t learning Cooperation or Trust: What comes first in the South China Sea? Israel Navy Dolphin-II class submarine Netherlands-Belgian Naval Squadron World Naval Developments The War of 1812: What it Means to the United States Flying the ASEAN Flag Centenary of ANZAC (Navy) The Far Flank of the Indo-Pacific: India and China in the South-West Pacific Confrontation at Sea: The Midshipman Who Almost Shot ‘The General’ JOURNAL OF THE Sponsorship_Ad_Outlines.indd 1 30/11/2013 10:43:20 PM Issue 152 3 Letter to the Editor Contents Dear Readers, As before, we require you to Australian Submarines from 1914 4 Headmark is going through conform to the Style Notes and other some changes. It will henceforth be guidelines printed at the back of the published constantly online, and paper edition, and also to be found on Africa’s Indian Ocean Navies: Naval in print twice a year, for June and the website. evolution in a complex and volatile December. The changes will bring more region 11 Publishing online will mean a steady immediacy, and less costs to the stream of articles reaching the website, ANI. Publishing world-wide is going The Aussie military history your kids which you can access at: through changes, and we are also aren’t learning 17 www.navalinstitute.com.au altering ourselves to best fit the new ANI members will have access to world. -

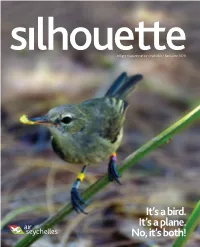

It's a Bird. It's a Plane. No, It's Both!

HM Silhouette Cover_Apr2019-Approved.pdf 1 08/03/2019 16:41 Inflight magazine of Air Seychelles • April-June 2020 It’s a bird. It’s a plane. No, it’s both! 9405 EIDC_Silhou_IBC 3/5/20 8:48 AM Page 5 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Composite [ CEO’S WELCOME ] Dear Guests, Welcome aboard! As you are probably aware, the aviation industry globally is under considerable pressure over the issue of carbon emissions and its impact on climate change. At Air Seychelles we are indeed proud of the contribution we are making towards sustainable development. Following the successful delivery of our second Airbus A320neo aircraft, Pti Merl Dezil in March 2020, I am pleased to announce that Air Seychelles is now operating the youngest jet fleet in the Indian Ocean. Performing to standard, the new engine option aircraft is currently on average generating 20% fuel savings per flight and 50% reduced noise footprint. This amazing performance cannot go unnoticed and we remain committed to further implement ecological measures across our business. Apart from keeping Seychelles connected through air access, Air Seychelles also provides ground handling services to all customer airlines operating at the Seychelles International Airport. Following an upsurge in the number of carriers coming into the Seychelles, in 2019 we surpassed the 1 million passenger threshold handled at the airport, recording an overall growth of 5% increase in arrival and departures. Combining both inbound and outbound travel including the domestic network, Air Seychelles alone contributed a total of 414,088 passengers after having operated 1,983 flights. -

Copyright © 2016 by Bonnie Rose Hudson

Copyright © 2016 by Bonnie Rose Hudson Select graphics used by permission of Teachers Resource Force. All Rights Reserved. This book may not be reproduced or transmitted by any means, including graphic, electronic, or mechanical, without the express written consent of the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews and those uses expressly described in the following Terms of Use. You are welcome to link back to the author’s website, http://writebonnierose.com, but may not link directly to the PDF file. You may not alter this work, sell or distribute it in any way, host this file on your own website, or upload it to a shared website. Terms of Use: For use by a family, this unit can be printed and copied as many times as needed. Classroom teachers may reproduce one copy for each student in his or her class. Members of co-ops or workshops may reproduce one copy for up to fifteen children. This material cannot be resold or used in any way for commercial purposes. Please contact the publisher with any questions. ©Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com 2 World War I Notebooking Unit The World War I Notebooking Unit is a way to help your children explore World War I in a way that is easy to personalize for your family and interests. In the front portion of this unit you will find: How to use this unit List of 168 World War I battles and engagements in no specific order Maps for areas where one or more major engagements occurred Notebooking page templates for your children to use In the second portion of the unit, you will find a list of the battles by year to help you customize the unit to fit your family’s needs. -

Queensland at War

ANZAC LEGACY GALLERY Large Print Book Queensland at War PROPERTY OF QUEENSLAND MUSEUM Contents 5 ...... Gallery Map 6 ...... Gallery introduction 7 ...... Queensland at War introduction 9 ...... Queensland at War - hats 10 .... Together 23 .... Loss 33 .... Wounded 44 ... Machine 63 .... World 78 .... Honour 92 .... Memories 4 Gallery Map 5 Entry Introductory panels Lift Interactives Gallery introduction 6 Queensland at War introduction 7 QUEENSLAND AT WAR People ... Queenslanders ... nearly 58,000 of them, left our shores for the war to end all wars. There are so many stories of the First World War – of people, experiences, and places far away – that changed our State forever. A small thing – like a medal crafted from bronze and silk – can tell an epic story of bravery, fear, and adventure; of politics, religion, and war. It represents the hardship and sacrifice of the men and women who went away, and the more than 10,000 Queenslanders who gave their lives for their country. Queensland at War introduction 8 First group of soldiers from Stanthorpe going to the war, seen off at Stanthorpe Station, 1914 Queensland Museum collection Queensland at War - hats 9 Military cap belonging to Percy Adsett, who served at Gallipoli in 1915 and was wounded at Pozieres in September 1916 Prussian infantryman’s pickelhaube acquired as a trophy on the Western Front in 1917 Nurses cap used by Miss Evelyn Drury when she was in the Voluntary Aid Detachment working at Kangaroo Point Military Hospital during World War 1 British Mark 1 Brodie Helmet, developed in the First World War as protection against the perils of artillery Together 10 Together CHARITY AND FUNDRAISING Charities like the Red Cross and ‘Patriotic’ and ‘Comfort Funds’ aided soldiers at the front and maintained morale at home.