Imagining Ruins in Ancient Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2013 Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Custom Citation Kinney, Dale. "Spoliation in Medieval Rome." In Perspektiven der Spolienforschung: Spoliierung und Transposition. Ed. Stefan Altekamp, Carmen Marcks-Jacobs, and Peter Seiler. Boston: De Gruyter, 2013. 261-286. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/70 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Topoi Perspektiven der Spolienforschung 1 Berlin Studies of the Ancient World Spoliierung und Transposition Edited by Excellence Cluster Topoi Volume 15 Herausgegeben von Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler De Gruyter De Gruyter Dale Kinney Spoliation in Medieval Rome i% The study of spoliation, as opposed to spolia, is quite recent. Spoliation marks an endpoint, the termination of a buildlng's original form and purpose, whÿe archaeologists tradition- ally have been concerned with origins and with the reconstruction of ancient buildings in their pristine state. Afterlife was not of interest. Richard Krautheimer's pioneering chapters L.,,,, on the "inheritance" of ancient Rome in the middle ages are illustrated by nineteenth-cen- tury photographs, modem maps, and drawings from the late fifteenth through seventeenth centuries, all of which show spoliation as afalt accomplU Had he written the same work just a generation later, he might have included the brilliant graphics of Studio Inklink, which visualize spoliation not as a past event of indeterminate duration, but as a process with its own history and clearly delineated stages (Fig. -

Ancient Civilizations UNIT 2

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=A UNIT 2: Informative Essay Ancient Civilizations © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company • Image ©DmitryCredits: Pichugin/Fotolia 31 9_LNLEAS147591_U2O.indd 31 5/30/13 1:44 PM DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=A UNIT 2 Informative Essay n informative essay, also called an expository ANALYZE essay, is a short work of nonfiction that informs Aand explains. Unlike fiction, nonfiction is mainly THE MODEL written to convey factual information, although writers Evaluate informative essays of nonfiction shape information in a way that matches on Cuzco, Peru, and Machu their own purposes. Nonfiction writing can be found in Picchu. newspaper, magazine, and online articles, as well as in biographies, speeches, movie and book reviews, and true-life adventure stories. The nonfiction topics that you will read about in this unit discuss real facts and events about ancient civilizations and structures. PRACTICE In thIs UnIt, you will analyze information from THE TASK nonfiction articles, graphics, and data displays. You will Write a comparison/ study a variety of text structures that are frequently contrast essay on how used in the writing of informative text. You will use the Mayan and Egyptian these text structures to plan and write your essays. pyramids are alike and different. PERFORM THE TASK Write an informative essay about the successes of the Maya, the Aztecs, and the Inca. © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company 32 9_LNLEAS147591_U2O.indd -

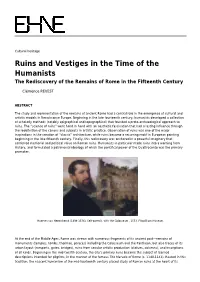

Ruins and Vestiges in the Time of the Humanists the Rediscovery of the Remains of Rome in the Fifteenth Century

Cultural heritage Ruins and Vestiges in the Time of the Humanists The Rediscovery of the Remains of Rome in the Fifteenth Century Clémence REVEST ABSTRACT The study and representation of the remains of ancient Rome had a central role in the emergence of cultural and artistic models in Renaissance Europe. Beginning in the late fourteenth century, humanists developed a collection of scholarly methods (notably epigraphical and topographical) that founded a proto-archaeological approach to ruins. The “science of ruins” went hand in hand with an aesthetic fascination that had a lasting influence through the redefinition of the canons and subjects in artistic practice. Observation of ruins was one of the major inspirations in the creation of “classic” architecture, while ruins became a recurring motif in European painting beginning in the late fifteenth century. Finally, this rediscovery was anchored in a powerful imaginary that conferred memorial and political value on Roman ruins. Humanists in particular made ruins into a warning from History, and formulated a patrimonial ideology of which the pontifical power of the Quattrocento was the primary promoter. Maerten van Heemskerck (1498-1574), Self-portrait, with the Colosseum , 1553. Fitzwilliam Museum. At the end of the Middle Ages, Rome was strewn with numerous fragments of its ancient past—remains of monuments (temples, tombs, thermae, palaces) including the Colosseum and the Pantheon, but also traces of its urban layout (ramparts, gates, bridges), ruins from secular artistic production (statues, columns), and inscriptions of all kinds. Beginning in the mid-twelfth century, the city’s primary ruins became the subject of learned descriptions intended for pilgrims, in the manner of the famous The Marvels of Rome (c. -

From Rome to Athens 9 – 13 DAYS

From Rome to Athens 9 – 13 DAYS From Rome to Athens Italy • Greece Extension includes Turkey Program Fee includes: • Round-trip airfare • 6 overnight stays in hotels with private bathrooms; plus 1 night cabin accommodation (5 with extension) • Complete European breakfast and dinner daily (3 meals daily on cruise extension) • Full-time bilingual EF Tour Director • 8 sightseeing tours led by licensed local guides; Vatican and Rome sightseeing tours includes headsets • 10 visits to special attractions • 2 EF walking tours The Acropolis towers over the center of Athens; its name translates to “city on the edge.” Highlights: Colosseum; Sistine Chapel: St. Peter’s Basilica; Spanish Steps; Pompeii Roman ruins; Olympia; Epidaurus; Mycenae; Acropolis; Agora site Day 1 Flight watchful eyes of the brightly dressed Swiss Gaurd. and Athenian cemetery; Delphi site and museum With extension: cruise ports: Mykonos; Kusadasi; Overnight flight to Italy • Relax as you fly across Inside, admire Michelangelo’s Pietá, the only Patmos; Rhodes; Heraklion; Santorini the Atlantic. sculpture he ever signed. Guided sightseeing of Rome • Pass the grassy Optional: Greek Evening Day 2 Rome ruins of the ancient Forum Romanum, once the Arrival in Rome • Touch down in bella Roma, the heart of the Roman Empire, and admire the Eternal City. Here Charlemagne was crowned enduring fragments of Rome’s glorious past. It Learn before you go emperor by the pope in A.D. 800. After clearing was here that business, commerce and the admin- www.eftours.com/pbsitaly customs you are greeted by your bilingual EF istration of justice once took place. Then vist the www.eftours.com/pbsgreece Tour Director, who will remain with you mighty Colosseum, Rome’s first permanent throughout your stay. -

Ruins to Conservation and Management © Commonwealth of Australia 2013

A guideRuins to conservation and management © Commonwealth of Australia 2013 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Department of the Environment, GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 or email [email protected] The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment. Cover photo: Marble Hill (SA Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources). A guide Ruinsto conservation and management Photo: Penitentiary building—simply maintain (Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority). Ruins a guide to conservation and management Contents 1. Introduction 7 2. What is a heritage ruin? 9 3. Why keep and protect heritage ruins? 13 4. Why do ruins pose particular challenges? 19 5. Principles 23 6. Management approaches for heritage ruins 25 7. Tools and techniques 39 8. Case studies 47 9. Glossary 63 10. For further guidance 67 5 Photo: Holy Trinity Anglican Church School (Department of the Environment). Ruins a guide to conservation and management 1. Introduction A place can become a ruin because it lacks a current purpose, is disused, has been abandoned or has been affected by disaster. Ruins can be a challenge for heritage property owners and managers due to their deteriorated condition and location. Conserving a ruin can often appear to be more expensive, time-consuming or requiring of specialist skills than conserving other heritage places. -

The Ruin of the Roman Empire

7888888888889 u o u o u o u THE o u Ruin o u OF THE o u Roman o u o u EMPIRE o u o u o u o u jamesj . o’donnell o u o u o u o u o u o u o hjjjjjjjjjjjk This is Ann’s book contents Preface iv Overture 1 part i s theoderic’s world 1. Rome in 500: Looking Backward 47 2. The World That Might Have Been 107 part ii s justinian’s world 3. Being Justinian 177 4. Opportunities Lost 229 5. Wars Worse Than Civil 247 part iii s gregory’s world 6. Learning to Live Again 303 7. Constantinople Deflated: The Debris of Empire 342 8. The Last Consul 364 Epilogue 385 List of Roman Emperors 395 Notes 397 Further Reading 409 Credits and Permissions 411 Index 413 About the Author Other Books by James J. O’ Donnell Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher preface An American soldier posted in Anbar province during the twilight war over the remains of Saddam’s Mesopotamian kingdom might have been surprised to learn he was defending the westernmost frontiers of the an- cient Persian empire against raiders, smugglers, and worse coming from the eastern reaches of the ancient Roman empire. This painful recycling of history should make him—and us—want to know what unhealable wound, what recurrent pathology, what cause too deep for journalists and politicians to discern draws men and women to their deaths again and again in such a place. The history of Rome, as has often been true in the past, has much to teach us. -

THE VANISHING PARADIGM of the FALL of ROME Glen W

BULLETIN THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES VoL. XLIX MAY 1996 No. 8 STATED MEETING ANNOUNCEMENT James Q. Wilson on CRIME AND JUSTICE IN ENGLAND AND AMERICA May 8, 1996 Cambridge, Massachusetts 3 ACADEMY POSITIONS OPEN IN 1997 5 THE 1996 RUMFORD PRIZE Awarded to John Cromwell Mather 8 100 MOST INFLUENTIAL BOOKS 12 PROJECT REPORT CULTURE AND THE PRODUCTION OF INSECURITY 19 STATED MEETING REPORT THE VANISHING PARADIGM OF THE FALL OF ROME Glen W. Bowersock 29 This content downloaded from 128.112.203.193 on Mon, 22 Oct 2018 14:21:30 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Stated Meeting Report The Vanishing Paradigm of the Fall of Rome Glen W. Bowersock When the first volume of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon was delivered to the public on Feb- ruary 17, 1776, it proved to be a huge and instant success. Its author observed in his Memoirs, "My book was on every table, and almost on every toilette." Two days after its publication the work was hailed as a classic by Horace Walpole, who found its style "as smooth as a Flemish picture." David Hume read the history in the short time that re- mained to him before his death in the same year, and he wrote to Gibbon, "Whether I consider the dignity of your style, the depth of your matter, or the extensiveness of your learning, I must regard the work as equally the object of esteem." Adam Ferguson com- pared Gibbon to Thucydides and declared the Decline and Fall "what Thucydides pro- posed leaving with his own countrymen, a possession in perpetuity." It is not so often that the judgment of contemporaries is confirmed by the judg- ment of posterity, but Gibbon's work is no less admired today than it was two centuries ago. -

The Lost City Campaign Sourcebook

Dungeon Module B4 T h e L o st C ity by Tom Moldvay The Lost City AN ADVENTURE FOR CHARACTER LEVELS Campaign1-3 Sourcebook a collection of original work and material gathered from the pages of Dragonsfoot and elsewhere on the internet with contributions by: Andy Campbell, Jason Cone, Lowell Francis, Geoff Gander, Jim Holloway, Zach Howard, Michael Kaluta, Bob Kindel, Luc Le Quiniat, James Maliszewski, Mike Monaco, M.W. Poort (Fingolwyn), Scott Rogers, Demos Sachlas, and Tom edited by Demos Sachlas March, 2018 Lost in the desert! The only hope for survival lies in a ruined city rising out of the sands. Food, water, and wealth await heroic adventurers inside an ancient pyramid ruled by a strange race of masked beings. This module includes a cover folder with maps, and a descriptive booklet with a ready-made adventure for the DUNGEON & DRAGONS® Basic game. It also includes enough information to continue the adventure beyond level 3, using the DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® Expert game rules. DUNGEONS & DRAGONS and D&D are registered trademarks of TSR Hobbies, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. Distributed in the United Kingdom by TSR Hobbies (UK) Ltd. © 1982 TSR Hobbies, Inc. All Rights Reserved. © 1 980 TS R Ho bbie s. Inc All Rights Re ser ve d IS B N 0 -93 56 96 -55-5 P R I N TED I N U.S.A . 9049 Table of Contents Retrospective: The Lost City 3 Expanding the Adventure 21 by James Maliszewski by -

The Ruins of Harappa Were Discovered in 1921 and Named After The

Click to reveal notes The ruins of Harappa A year after Harappa The civilization of were discovered in was discovered, the Harappa lasted for 1921 and named ruins of Mohenjo-Daro about 1000 years. after the nearby were found 400 miles village of Harappa SW of Harappa. The Lost Cities The great bath found Mohenjo-Daro of the Indus in Mohenjo-Daro might was a planned have been used for city of about religious ceremonies. 40,000 people, laid out in a grid, with paved Mohenjo-Daro streets at right means angles. “Mound of the Dead” A citadel is a strong in Sanskrit. fortress with thick walls to protect it. Almost identical Planned Cities-- Harappan cities layouts of Harappa Standard had sewer and Mohenjo-Daro measurements were systems, and indicate that there was used to make bricks many homes had probably a strong that were all the same toilets. central government size. that planned the cities. Harappan Culture Trade routes (Khyber Conclusions about Harappan culture are Pass) connected the Indus Specialized skills-- based on artifacts and Valley and Mesopotamia. Ancient Harappans remains of Mohenjo-Daro. Indus Valley traders traded were skilled engineers ivory, copper, and beads and craftworkers, for cloth, oil, and barley. making elegant jewelry, beautiful Harappans grew new seals, and decorated crops, like cotton, pottery, as well as mustard, and black Surplus food copper fish pepper, as well as wheat, allowed for the hooks. bananas, barley, and specialization of sesame jobs. Cities of the Indus About 1500 BC, a Valley were abandoned group of people from about 1600 BC, Asia, called the Aryans, Aryans means possibly because of crossed the Hindu- “noble ones” in earthquake, drought, Kush mountains into Sanskrit. -

Greece: Ancient Ruins & Iconic Islands

Privacy Notice: We use technologies on our website for personalizing content, advertising, providing social media features, and analyzing our traffic. We also share information about your use of our site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners. By continuing to use this website, you consent to our use of this technology. You can control this through your Privacy Options. Accept Last Updated: June 8, 2021 Greece: Ancient Ruins & Iconic Islands - EGANG 12 days: Athens to Athens What's Included • Your Journeys Highlight Moment: Ancient Athens Tour with an Archaeologist, Athens • Your Journeys Highlight Moment: Athens Culinary Mezze Experience, Athens • Your G for Good Moment: Tour of Shedia Home and a Beverage, Athens • Guided visit of Acropolis and Parthenon • Guided tour of Ancient Delphi • Delphi Archaeological Museum visit • Olympia Archaeological Site and Museum visit • Guided tour of Mycenae • Epidaurus and Ancient Corinth Ruins visit • Santorini Sailing Excursion • Orientation walks in Athens, Delphi and N■xos • All transport between destinations and to/from included activities The information in this trip details document has been compiled with care and is provided in good faith. However it is subject to change, and does not form part of the contract between the client and G Adventures. The itinerary featured is correct at time of printing. It may differ slightly to the one in the brochure. Occasionally our itineraries change as we make improvements that stem from past travellers, comments and our own research. Sometimes it can be a small change like adding an extra meal along the itinerary. Sometimes the change may result in us altering the tour for the coming year. -

Abstract Every City Has Its Modern Ruins, Whether Post-Industrial

Abstract Every city has its modern ruins, whether post-industrial remains rusting away; derelict houses falling into the street; or rows of empty and neglected shopfronts reminiscent of Walter Benjamin’s Parisian arcades. This chapter explores the associations with Benjamin’s work that can be brought forth through the contrast of the active and inhabited city, and ruinous architectural remnants – real and imagined – revealing the end of the city as the other face of modernity and history, made present in the critical formation of the modern ruin. Urban endings are characterised through the register of the imagined, and the politics of imagination, as much as material encounter. Modern ruins sustain alternative imaginaries of the city (as a concept) through the contrasting visions of the city as a site of ruin, and the city as a seamlessly planned environment. The power of such imagination to impact everyday experience evokes a distinctly Benjaminian reversal of progress, which he identified in the semi-abandoned Arcades, and which extends to modern ruins that evoke the end of the city, when architecture and technological forms are rendered useless and obsolete. Considering modern ruins (real and imagined), this chapter considers the relation between the materiality of contemporary architectural decay, and imagined urban endings. Through Walter Benjamin’s rubble-infused and urban-focused writings, modern ruins and urban endings reveal the transience of the city, its material decay and disappearance, reflecting the inherent flux and movement of the city. The chapter enacts Benjamin’s archaeological excavation of history in the present, where lived encounters and the act of reading flash up together with a multi-temporal recognition of the moment through the ruinous allegorical mode that takes modern ruin and urban endings as the site of critique. -

•Œex Nihilo Fortification on the Brabant-Namur Frontier in the High

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 4 Issue 4 30-49 2014 “Ex nihilo fortification on the Brabant-Namur Frontier in the High Middle Ages,” Walhain Research Project Bailey K. Young Eastern Illinois University and Laurent Verslype, Université Catholique de Louvain Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Young, Bailey K.. "“Ex nihilo fortification on the Brabant-Namur Frontier in the High Middle Ages,” Walhain Research Project." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 4, 4 (2014): 30-49. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol4/iss4/3 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Young “Ex nihilo fortification on the Brabant-Namur Frontier in the High Middle Ages,” Walhain Research Project1 By Bailey K. Young, Eastern Illinois University and Laurent Verslype, Université Catholique de Louvain On the south side of the village of Walhain-Saint-Paul in Walloon Brabant a round donjon tower stands looking over the cultivated fields southwest toward Gembloux, once the site of a renowned Benedictine abbey that, according to a charter of 946, owned the land on which the tower would later be built (Figure 1).2 Presumably its construction took place around 1200, the moment when the vogue for this circular form, called tour philippienne after the prototype that the French King Philip II had erected in Paris and elsewhere in his domains, was spreading.