Indian Mountaineering Foundation Newsletter * Volume 9 * July 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLACIERS of NEPAL—Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range

Glaciers of Asia— GLACIERS OF NEPAL—Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range By Keiji Higuchi, Okitsugu Watanabe, Hiroji Fushimi, Shuhei Takenaka, and Akio Nagoshi SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD Edited by RICHARD S. WILLIAMS, JR., and JANE G. FERRIGNO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1386–F–6 CONTENTS Glaciers of Nepal — Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range, by Keiji Higuchi, Okitsugu Watanabe, Hiroji Fushimi, Shuhei Takenaka, and Akio Nagoshi ----------------------------------------------------------293 Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------------293 Use of Landsat Images in Glacier Studies ----------------------------------293 Figure 1. Map showing location of the Nepal Himalaya and Karokoram Range in Southern Asia--------------------------------------------------------- 294 Figure 2. Map showing glacier distribution of the Nepal Himalaya and its surrounding regions --------------------------------------------------------- 295 Figure 3. Map showing glacier distribution of the Karakoram Range ------------- 296 A Brief History of Glacier Investigations -----------------------------------297 Procedures for Mapping Glacier Distribution from Landsat Images ---------298 Figure 4. Index map of the glaciers of Nepal showing coverage by Landsat 1, 2, and 3 MSS images ---------------------------------------------- 299 Figure 5. Index map of the glaciers of the Karakoram Range showing coverage -

Glacier Elevation and Mass Changes in Himalayas During 2000-2014

The Cryosphere Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2019-85 Manuscript under review for journal The Cryosphere Discussion started: 29 April 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Glacier elevation and mass changes in Himalayas during 2000-2014 Debmita Bandyopadhyay1, Gulab Singh1, Anil V.Kulkarni2 1Center of Studies in Resources Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, 400076, India 5 2Divecha Centre for Climate Change, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, 560012, India Abstract Glacier mass balance is a crucial parameter to understand the changes in glaciers. For the Himalayas, it is more complex as glaciers have a heterogeneous pattern of elevation and mass changes. In this study, 10 mass balance using geodetic method is estimated, for which we utilize SRTM and TanDEM-X global digital elevation models (DEMs) of the year 2000 and 2012-2014 respectively. The unique feature of this study is that the dataset are prepared using repeat bistatic synthetic aperture radar interferometry which has not been used over the rugged Himalayan terrains on such a large-scale. The elevation and mass change measurements cover seven states namely Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, 15 Uttarakhand, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh. The mean elevation change is -0.45 ± 0.40 m yr -1 and the mass budget is -11.24 ± 0.79 Gt yr -1. However, the cumulative mass loss over the observation period of 2000-2014 is -154.72 ± 19.04 Gt which accounts for approximately 5% of the total ice-mass present in the Indian Himalayas. This ice-mass loss contributes to 0.42 ± 0.05 mm of sea- level rise. -

1) Consider the Following Statements with Respect to Shram Shakti Portal

Daily Current Affairs Prelims Quiz - 22-01-2021 - (Online Prelims Test) 1) Consider the following statements with respect to Shram Shakti Portal 1. It is a National Migration Support Portal to help migrant workers. 2. It was launched by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs. Which of the statement(s) given above is/are correct? a. 1 only b. 2 only c. Both 1 and 2 d. Neither 1 nor 2 Answer : c In a move that would effectively help in the smooth formulation of State and National level programs for migrant workers, the Union Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA) is launching Shram Shakti and Shram Saathi. ShramShakti – It is a National Migration Support Portal. Shram Saathi – It is a training manual for migrant workers at Goa. To facilitate and support approximately 4 lakhs migrants who come from different States to Goa, Chief Minister of Goa will also launch dedicated Migration cell in Goa. MoTA has also sanctioned Tribal research Institute, Tribal Museum, Van Dhan Kendras and Tribal Lok Utsav in Goa. 2) Consider the following statements with respect to India Science 1. It is an Internet-based science Over-The-Top (OTT) TV channel initiated by the Department of Science and Technology. 2. It has been implemented and managed by Prasar Bharati, an autonomous organization of the Department of Information and Broadcasting. Which of the statement(s) given above is/are correct? a. 1 only b. 2 only c. Both 1 and 2 d. Neither 1 nor 2 Answer : a India Science, Nation’s Science & Technology OTT (Over-the-top) channel has completed its second year of existence. -

A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya

The Himalaya by the Numbers A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya Richard Salisbury Elizabeth Hawley September 2007 Cover Photo: Annapurna South Face at sunrise (Richard Salisbury) © Copyright 2007 by Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley No portion of this book may be reproduced and/or redistributed without the written permission of the authors. 2 Contents Introduction . .5 Analysis of Climbing Activity . 9 Yearly Activity . 9 Regional Activity . .18 Seasonal Activity . .25 Activity by Age and Gender . 33 Activity by Citizenship . 33 Team Composition . 34 Expedition Results . 36 Ascent Analysis . 41 Ascents by Altitude Range . .41 Popular Peaks by Altitude Range . .43 Ascents by Climbing Season . .46 Ascents by Expedition Years . .50 Ascents by Age Groups . 55 Ascents by Citizenship . 60 Ascents by Gender . 62 Ascents by Team Composition . 66 Average Expedition Duration and Days to Summit . .70 Oxygen and the 8000ers . .76 Death Analysis . 81 Deaths by Peak Altitude Ranges . 81 Deaths on Popular Peaks . 84 Deadliest Peaks for Members . 86 Deadliest Peaks for Hired Personnel . 89 Deaths by Geographical Regions . .92 Deaths by Climbing Season . 93 Altitudes of Death . 96 Causes of Death . 97 Avalanche Deaths . 102 Deaths by Falling . 110 Deaths by Physiological Causes . .116 Deaths by Age Groups . 118 Deaths by Expedition Years . .120 Deaths by Citizenship . 121 Deaths by Gender . 123 Deaths by Team Composition . .125 Major Accidents . .129 Appendix A: Peak Summary . .135 Appendix B: Supplemental Charts and Tables . .147 3 4 Introduction The Himalayan Database, published by the American Alpine Club in 2004, is a compilation of records for all expeditions that have climbed in the Nepal Himalaya. -

In Memoriam I Met Ralph in 1989 When I Moved to Wolverhampton, Through Our Involvement with the Wolverhampton Mountain- Eering Club

Obituaries Matterhorn. Edward Theodore Compton. 1880. Watercolour. 43 x 68cm. (Alpine Club Collection HE118P) 399 I N M E M ORI am 401 Ralph Atkinson 1952 - 2014 In Memoriam I met Ralph in 1989 when I moved to Wolverhampton, through our involvement with the Wolverhampton Mountain- eering Club. Weekends in Wales The Alpine Club Obituary Year of Election and day trips to Matlock and the (including to ACG) Roaches became the foundation for extended expeditions to the Ralph Atkinson 1997 Alps including, in 1991, a fine Una Bishop 1982 six-day ski traverse of the Haute John Chadwick 1978 Route, Argentière to Zermatt, John Clegg 1955 and ascents in 1993 of the Mönch Dennis Davis 1977 and Jungfrau. Descending the Gordon Gadsby 1985 Jungfrau in a storm, we could Johannes Villiers de Graaff 1953 barely see each other. I slipped David Jamieson 1999 in the new snow and had to self- Emlyn Jones 1944 arrest, aided by the tension in the Brian ‘Ned’ Kelly 1968 rope to Ralph. It worked, and I Neil Mackenzie Asp.2011, 2015 Ralph Atkinson climbing on the slabs of Fournel, was soon back on the ridge, but Richard Morgan 1960 near Argentière, Ecrins. (Andy Clarke) when we dropped below the John Peacock 1966 Rottalsattel and could speak to Bill Putnam 1972 each other again, he had no idea that anything untoward had happened. Stephanie Roberts 2011 I recall long journeys by car enlivened by his wide-ranging taste in music. Les Swindin 1979 The keynote of many outings was his sense of fun. There were long stories, John Tyson 1952 jokes or pithy one-liners. -

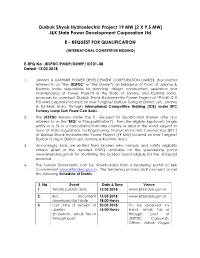

Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Project 19 MW (2 X 9.5 MW) J&K State Power Development Corporation Ltd

Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Project 19 MW (2 X 9.5 MW) J&K State Power Development Corporation Ltd. E - REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATION (INTERNATIONAL COMPETITIVE BIDDING) E-RFQ No: JKSPDC/PMDP/DSHEP/10101-08 Dated: 13.03.2018 1. JAMMU & KASHMIR POWER DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LIMITED, (hereinafter referred to as “the JKSPDC" or "the Owner”) an Enterprise of Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir, India, responsible for planning, design, construction, operation and maintenance of Power Projects in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, India, proposes to construct Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Power Project of 19 MW (2 X 9.5 MW) capacity located on river Tangtse/ Durbuk Gong in District Leh, Jammu & Kashmir, India, through International Competitive Bidding (ICB) under EPC Turnkey Lump Sum Fixed Cost Basis. 2. The JKSPDC hereby invites the E - Request for Qualification (herein after also referred to as the "RFQ" or "Prequalification") from the eligible Applicants (single entity or a JV or a consortium) from any country or area in the world subject to Govt of India regulations, for Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) of Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Power Project (19 MW) located on river Tangtse/ Durbuk Gong in District Leh, Jammu & Kashmir, India. 3. Accordingly, bids are invited from bidders who comply and satisfy eligibility criteria given in the detailed E-RFQ available on the e-tendering portal www.jktenders.gov.in for shortlisting the bidders found eligible for the aforesaid proposal. 4. The Tender Documents can be downloaded from e-tendering portal of J&K Government www.jktenders.gov.in . The tendering process shall proceed as per the following Schedule of Events: S. -

Monsoon-Influenced Glacier Retreat in the Ladakh Range, Jammu And

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 18, EGU2016-166, 2016 EGU General Assembly 2016 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Monsoon-influenced glacier retreat in the Ladakh Range, Jammu and Kashmir Tom Chudley, Evan Miles, and Ian Willis Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge ([email protected]) While the majority of glaciers in the Himalaya-Karakoram mountain chain are receding in response to climate change, stability and even growth is observed in the Karakoram, where glaciers also exhibit widespread surge- type behaviour. Changes in the accumulation regime driven by mid-latitude westerlies could explain such stability relative to the monsoon-fed glaciers of the Himalaya, but a lack of detailed meteorological records presents a challenge for climatological analyses. We therefore analyse glacier changes for an intermediate zone of the HKH to characterise the transition between the substantial retreat of Himalayan glaciers and the surging stability of Karakoram glaciers. Using Landsat imagery, we assess changes in glacier area and length from 1991-2014 across a ∼140 km section of the Ladakh Range, Jammu and Kashmir. Bordering the surging, stable portion of the Karakoram to the north and the Western Himalaya to the southeast, the Ladakh Range represents an important transitional zone to identify the potential role of climatic forcing in explaining differing glacier behaviour across the region. A total of 878 glaciers are semi-automatically identified in 1991, 2002, and 2014 using NDSI (thresholds chosen between 0.30 and 0.45) before being manually corrected. Ice divides and centrelines are automatically derived using an established routine. Total glacier area for the study region is in line with that Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI) and ∼25% larger than the GLIMS Glacier Database, which is apparently more conservative in assigning ice cover in the accumulation zone. -

Abode of Goddess Sharda

Abode of Goddess Sharda At Shardi I – Mother’s Grace {Mahima}, Sharda Mahatmaya And Grandeur - Brigadier Rattan Kaul {I dedicate this effort to Grace {Mahima} of Goddess Sharda for the benefit of my and Gen-X, who may not know much about Goddess Sharda and her implied benevolence to our Sharda Desh. This article is also a gift to Gen-X, like Naveen, who know more of our religion, culture and heritage than men of their age. Along with era scholars and personalities associated with Sharda Temple during various century’s, I have given brief details about them to make it more informative. Each part is self explanatory with notes to avoid reference to previous part.…Rattan} Mahima {Grace} Of Mother Sharda. As a young boy I got used to hear folk tales of Sone Kisli and other tales from Granny Zapar Ded, but what interested me was her narration of travelogue of Pandit Bhawani Kaul of 18th Century {Descendant of Pandit Narain Kaul; who wrote History of Kashmir during Akbar’s time}. His travels through dense forests in quest of spiritual and literary enlightenment kept me, an eight-year-old, gazing at her next lip movement, however, it was Bhawani Kaul’s challenging pilgrimage to Gangabal and Sharda Temple which impressed me most. At Matamal uncle would hold court at his Rehbab Sahib residence and amongst various discourses, Pandit Harjoo Fehrist’s {Mid 19th Century; social reformer and staunch Vedhist} visits to Sharda Temple, till he lost his life at the temple, held us spell bound. Those days Goddess Sharda meant a lot to me, in my quest to do well in studies. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-Hðgå-ÅÛ-Hýh-ºiô-;Ým-Mû-Ç+Ô¼-¾-Zçàz-Çeômü

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-hÝh-ºIô-;Ým-mÛ-Ç+ô¼-¾-zÇÀz-Çeômü Tahir Shawl Jigmet Takpa Phuntsog Tashi Yamini Panchaksharam 2 FOREWORD Ladakh is one of the most wonderful places on earth with unique biodiversity. I have the privilege of forwarding the fi eld guide on mammals of Ladakh which is part of a series of bilingual (English and Ladakhi) fi eld guides developed by WWF-India. It is not just because of my involvement in the conservation issues of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, but I am impressed with the Ladakhi version of the Field Guide. As the Field Guide has been specially produced for the local youth, I hope that the Guide will help in conserving the unique mammal species of Ladakh. I also hope that the Guide will become a companion for every nature lover visiting Ladakh. I commend the efforts of the authors in bringing out this unique publication. A K Srivastava, IFS Chief Wildlife Warden, Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir 3 ÇSôm-zXôhü ¾-hÐGÅ-mÛ-ºWÛG-dïm-mP-¾-ÆôG-VGÅ-Ço-±ôGÅ-»ôh-źÛ-GmÅ-Å-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-ŸÛG-»Ûm-môGü ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Å-GmÅ-;Ým-¾-»ôh-qºÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚Å-q-ºhÛ-¾-ÇSôm-zXôh-‚ô-‚Å- qôºÛ-PºÛ-¾Å-ºGm-»Ûm-môGü ºÛ-zô-P-¼P-W¤-¤Þ-;-ÁÛ-¤Û¼-¼Û-¼P-zŸÛm-D¤-ÆâP-Bôz-hP- ºƒï¾-»ôh-¤Dm-qôÅ-‚Å-¼ï-¤m-q-ºÛ-zô-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Ç+h-hï-mP-P-»ôh-‚Å-qôº-È-¾Å-bï-»P- zÁh- »ôPÅü Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚ô-‚Å-qô-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-¾ÛÅ-GŸôm-mÝ-;Ým-¾-wm-‚Å-¾-ºwÛP-yï-»Ûm- môG ºô-zôºÛ-;-mÅ-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-Tm-mÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-BôzÅ-¾-wm-qºÛ-¼Û-zô-»Ûm- hôm-m-®ôGÅ-¾ü ¼P-zŸÛm-D¤Å-¾-ºfh-qô-»ôh-¤Dm-±P-¤-¾ºP-wm-fôGÅ-qºÛ-¼ï-z-»Ûmü ºhÛ-®ßGÅ-ºô-zM¾-¤²h-hï-ºƒÛ-¤Dm-mÛ-ºhÛ-hqï-V-zô-q¼-¾-zMz-Çeï-Çtï¾-hGôÅ-»Ûm-môG Íï-;ï-ÁÙÛ-¶Å-b-z-ͺÛ-Íïw-ÍôÅ- mGÅ-±ôGÅ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-Bôz-Çkï-DG-GÛ-hqôm-qô-G®ô-zô-W¤- ¤Þ-;ÁÛ-¤Û¼-GŸÝP.ü 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The fi eld guide is the result of exhaustive work by a large number of people. -

Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 17 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin: Article 16 Solukhumbu and the Sherpa 1997 Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal Alton C. Byers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Byers, Alton C.. 1997. Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal. HIMALAYA 17(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol17/iss2/16 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal Alton C. Byers The Mountain Institute This study uses repeat photography as the primary Introduction research tool to analyze processes of physical and Repeat photography, or precise replication and cultural landscape change in the Khumbu (M!. Everest) interpretation of historic landscape scenes, is an region over a 40-year period (1955-1995). The study is analytical tool capable of broadly clarifying the patterns a continuation of an on-going project begun by Byers in and possible causes of contemporary landscapellanduse 1984 that involves replication of photographs originally changes within a given region (see: Byers 1987a1996; taken between 1955-62 from the same five photo 1997). As a research tool, it has enjoyed some utility points. The 1995 investigation reported here provided in the United States during the past thirty years (see: the opportunity to expand the photographic data base Byers 1987b; Walker 1968; Heady and Zinke 1978; from five to 26 photo points between Lukla (2,743 m) Gruell 1980; Vale, 1982; Rogers et al. -

Everest – South Col Route – 8848M the Highest Mountain in the World South Col Route from Nepal

Everest – South Col Route – 8848m The highest mountain in the world South Col Route from Nepal EXPEDITION OVERVIEW Join Adventure Peaks on their twelfth Mt Everest Expedition to the world’s highest mountain at 8848m (29,035ft). Our experience is amongst the best in the world, combined with a very high success rate. An ultimate objective in many climbers’ minds, the allure of the world’s highest summit provides a most compelling and challenging adventure. Where there is a will, we aim to provide a way. Director of Adventure Peaks Dave Pritt, an Everest summiteer, has a decade of experience on Everest and he is supported by Stu Peacock, a regular and very talented high altitude mountaineer who has led successful expeditions to both sides of Everest as well as becoming the first Britt to summit Everest three times on the North Side. The expedition is a professionally-led, non-guided expedition. We say non-guided because our leader and Sherpa team working with you will not be able to protect your every move and you must therefore be prepared to move between camps unsupervised. You will have an experienced leader who has previous experience of climbing at extreme high altitude together with the support of our very experienced Sherpa team, thus increasing your chance of success. Participation Statement Adventure Peaks recognises that climbing, hill walking and mountaineering are activities with a danger of personal injury or death. Participants in these activities should be aware of and accept these risks and be responsible for their own actions and involvement. Adventure Travel – Accuracy of Itinerary Although it is our intention to operate this itinerary as printed, it may be necessary to make some changes as a result of flight schedules, climatic conditions, limitations of infrastructure or other operational factors.