Entfust,Ilh, Synthesis Alid Aiark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hunter Economic Zone

Issue No. 3/14 June 2014 The Club aims to: • encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat • encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity A Black-necked Stork pair at Hexham Swamp performing a spectacular “Up-down” display before chasing away the interloper - in this case a young female - Rod Warnock CONTENTS President’s Column 2 Conservation Issues New Members 2 Hunter Economic Zone 9 Club Activity Reports Macquarie Island now pest-free 10 Glenrock and Redhead 2 Powling Street Wetlands, Port Fairy 11 Borah TSR near Barraba 3 Bird Articles Tocal Field Days 4 Plankton makes scents for seabirds 12 Tocal Agricultural College 4 Superb Fairy-wrens sing to their chicks Rufous Scrub-bird Monitoring 5 before birth 13 Future Activity - BirdLife Seminar 5 BirdLife Australia News 13 Birding Features Birding Feature Hunter Striated Pardalote Subspecies ID 6 Trans-Tasman Birding Links since 2000 14 Trials of Photography - Oystercatchers 7 Club Night & Hunterbirding Observations 15 Featured Birdwatching Site - Allyn River 8 Club Activities June to August 18 Please send Newsletter articles direct to the Editor, HBOC postal address: Liz Crawford at: [email protected] PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Deadline for the next edition - 31 July 2014 Website: www.hboc.org.au President’s Column I’ve just been on the phone to a lady that lives in Sydney was here for a few days visiting the area, talking to club and is part of a birdwatching group of friends that are members and attending our May club meeting. -

Mount Lyell Abt Railway Tasmania

Mount Lyell Abt Railway Tasmania Nomination for Engineers Australia Engineering Heritage Recognition Volume 2 Prepared by Ian Cooper FIEAust CPEng (Retired) For Abt Railway Ministerial Corporation & Engineering Heritage Tasmania July 2015 Mount Lyell Abt Railway Engineering Heritage nomination Vol2 TABLE OF CONTENTS BIBLIOGRAPHIES CLARKE, William Branwhite (1798-1878) 3 GOULD, Charles (1834-1893) 6 BELL, Charles Napier, (1835 - 1906) 6 KELLY, Anthony Edwin (1852–1930) 7 STICHT, Robert Carl (1856–1922) 11 DRIFFIELD, Edward Carus (1865-1945) 13 PHOTO GALLERY Cover Figure – Abt locomotive train passing through restored Iron Bridge Figure A1 – Routes surveyed for the Mt Lyell Railway 14 Figure A2 – Mount Lyell Survey Team at one of their camps, early 1893 14 Figure A3 – Teamsters and friends on the early track formation 15 Figure A4 - Laying the rack rail on the climb up from Dubbil Barril 15 Figure A5 – Cutting at Rinadeena Saddle 15 Figure A6 – Abt No. 1 prior to dismantling, packaging and shipping to Tasmania 16 Figure A7 – Abt No. 1 as changed by the Mt Lyell workshop 16 Figure A8 – Schematic diagram showing Abt mechanical motion arrangement 16 Figure A9 – Twin timber trusses of ‘Quarter Mile’ Bridge spanning the King River 17 Figure A10 – ‘Quarter Mile’ trestle section 17 Figure A11 – New ‘Quarter Mile’ with steel girder section and 3 Bailey sections 17 Figure A12 – Repainting of Iron Bridge following removal of lead paint 18 Figure A13 - Iron Bridge restoration cross bracing & strengthening additions 18 Figure A14 – Iron Bridge new -

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration Along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History That Refl Ects National Trends

Two Centuries of Botanical Exploration along the Botanists Way, Northern Blue Mountains, N.S.W: a Regional Botanical History that Refl ects National Trends DOUG BENSON Honorary Research Associate, National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney NSW 2000, AUSTRALIA. [email protected] Published on 10 April 2019 at https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/LIN/index Benson, D. (2019). Two centuries of botanical exploration along the Botanists Way, northern Blue Mountains,N.S.W: a regional botanical history that refl ects national trends. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 141, 1-24. The Botanists Way is a promotional concept developed by the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden at Mt Tomah for interpretation displays associated with the adjacent Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA). It is based on 19th century botanical exploration of areas between Kurrajong and Bell, northwest of Sydney, generally associated with Bells Line of Road, and focussed particularly on the botanists George Caley and Allan Cunningham and their connections with Mt Tomah. Based on a broader assessment of the area’s botanical history, the concept is here expanded to cover the route from Richmond to Lithgow (about 80 km) including both Bells Line of Road and Chifl ey Road, and extending north to the Newnes Plateau. The historical attraction of botanists and collectors to the area is explored chronologically from 1804 up to the present, and themes suitable for visitor education are recognised. Though the Botanists Way is focused on a relatively limited geographic area, the general sequence of scientifi c activities described - initial exploratory collecting; 19th century Gentlemen Naturalists (and lady illustrators); learned societies and publications; 20th century publicly-supported research institutions and the beginnings of ecology, and since the 1960s, professional conservation research and management - were also happening nationally elsewhere. -

Sendle Zones

Suburb Suburb Postcode State Zone Cowan 2081 NSW Cowan 2081 NSW Remote Berowra Creek 2082 NSW Berowra Creek 2082 NSW Remote Bar Point 2083 NSW Bar Point 2083 NSW Remote Cheero Point 2083 NSW Cheero Point 2083 NSW Remote Cogra Bay 2083 NSW Cogra Bay 2083 NSW Remote Milsons Passage 2083 NSW Milsons Passage 2083 NSW Remote Cottage Point 2084 NSW Cottage Point 2084 NSW Remote Mccarrs Creek 2105 NSW Mccarrs Creek 2105 NSW Remote Elvina Bay 2105 NSW Elvina Bay 2105 NSW Remote Lovett Bay 2105 NSW Lovett Bay 2105 NSW Remote Morning Bay 2105 NSW Morning Bay 2105 NSW Remote Scotland Island 2105 NSW Scotland Island 2105 NSW Remote Coasters Retreat 2108 NSW Coasters Retreat 2108 NSW Remote Currawong Beach 2108 NSW Currawong Beach 2108 NSW Remote Canoelands 2157 NSW Canoelands 2157 NSW Remote Forest Glen 2157 NSW Forest Glen 2157 NSW Remote Fiddletown 2159 NSW Fiddletown 2159 NSW Remote Bundeena 2230 NSW Bundeena 2230 NSW Remote Maianbar 2230 NSW Maianbar 2230 NSW Remote Audley 2232 NSW Audley 2232 NSW Remote Greengrove 2250 NSW Greengrove 2250 NSW Remote Mooney Mooney Creek 2250 NSWMooney Mooney Creek 2250 NSW Remote Ten Mile Hollow 2250 NSW Ten Mile Hollow 2250 NSW Remote Frazer Park 2259 NSW Frazer Park 2259 NSW Remote Martinsville 2265 NSW Martinsville 2265 NSW Remote Dangar 2309 NSW Dangar 2309 NSW Remote Allynbrook 2311 NSW Allynbrook 2311 NSW Remote Bingleburra 2311 NSW Bingleburra 2311 NSW Remote Carrabolla 2311 NSW Carrabolla 2311 NSW Remote East Gresford 2311 NSW East Gresford 2311 NSW Remote Eccleston 2311 NSW Eccleston 2311 NSW Remote -

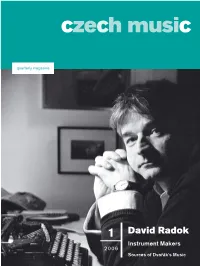

David Radok Instrument Makers 2006 Sources of Dvořák’S Music …Want to Learn More About Czech Music?

czech music quarterly magazine 1 David Radok Instrument Makers 2006 Sources of Dvořák’s Music …want to learn more about Czech music? …search for information about Czech musical life? www.musica.cz czech music contents 1/2006 In Opera Direction a Generalizing Approach Means the Absolute End. Interview with David Radok editorial RADMILA HRDINOVÁ Page 2 Václav František Červený - Master of his Craft GABRIELA NĚMCOVÁ A major theme in this issue of Czech Music Page 8 is the manufacture of musical instruments in the Czech Republic. When we look back on the history of instrument-making here, it Organ Building in the Czech Lands is hard not to feel a certain nostalgia and a PETR KOUKAL certain bitterness. In the Austro-Hungarian period and in the inter-war period under the Page 13 First Czechoslovak Republic this was a country with literally hundreds of instrument makers of all kinds, from the Manufacture of pianos in the Czech Republic: smallest to world famous firms. The Yesterday and Today communist nationalisation programme after 1948 and replacement of private enterprise TEREZA KRAMPLOVÁ by central planning had devastating Page 18 consequences for the music instrument industry, just as it had for the rest of the economy. There were, it is true, a few Four generations of Špidlens - The Legendary Violin Makers exceptions that remained capable of competing on world markets in terms of LIBUŠE HUBIČKOVÁ quality, but these were truly exceptions and Page 23 – above all – they cannot be used as arguments for the theory that is still heard too often, that “actually nothing so very The Composer Rudolf Komorous terrible happened”. -

The Magazine of the Nissan Patrol 4WD Club of NSW & ACT Inc

ON PATROL No 4. The Magazine of the Nissan Patrol 4WD Club of NSW & ACT Inc. April 2014 1 Nissan Patrol 4WD Club General Meetings 2nd Wednesday of each month at the Veteran Car Club 134 Queens Road Five Dock NSW 2046 Club mail can be sent to: Nissan Patrol 4WD Club PO Box 249 FIVE DOCK NSW 2046 The views expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the Nissan Patrol 4WD Club of NSW & ACT Inc. The Club and its officers do not expect nor invite any person to act or rely on any statement, opinion or advice. The Nissan Patrol 4WD Club website, www.nissanpatrolclub.org includes a "members only" area with access to details of upcoming trips and other news/information not meant for public consumption. To be issued a user name and password to access the website, please send an e-mail with your name and home phone number to [email protected]. Put "password required" in the subject area of the e-mail. After we have verified your details, you will receive an e-mail with your log-in information. C O N T E N T S About the Club 3 TR1 - There and Back Again 25 Committee Members 4 TR2 - Yerranderie 29 Editorial 5 TR3 - Barrington Tops 33 President’s Report 6 Bush Computer Terminology 37 2013 Club Awards 7 TR4 - March Working Bee 38 Get to Know... 11 TR5 - Committee Dinner 41 The Scoreboard 13 Tech Talk 42 Driver Training & Working Bees 14 DIY: Fire Starters 49 Club Calendar 15 Photo Competition 50 Trip Leaders & New Trips, Trip Bookings 20 Nature Lover 51 Trip Classification 21 Junior Patrollers 52 Radio Channels 22 Find-a-Word 53 Convoy Procedure 23 Club Noticeboard 54 4WDing Tips for Dummies 24 Camping Checklist 56 Front Cover: Ken S at November 2013 Driver Training. -

Mt Kosciuszko”

The known and less familiar history of the naming of “Mt Kosciuszko” Andrzej S. Kozek1 The highest peak on the continental Australia bears the name “Mt Kosciuszko” and we know this from our time in primary school. We as well remember that it was discovered and named by the Polish traveller and explorer, Paul Edmund de Strzelecki. Polish people consider it a magnificent monument to Tadeusz Kosciuszko. However, the history of its naming along with many related controversies are less familiar and lead to dissemination of incorrect information both in Poland and in Australia. Hence, to fill the gap, it is necessary to gather the facts in one publication equipped with references to the relevant historical resources. Key terms: Mt Kosciuszko, Tadeusz Kosciuszko, Kosciuszko's Will, Paul Edmund Strzelecki, Strzelecki, Australia, Aborigines, equality under the law, freedom, democracy. Macarthur and Strzelecki’s Expedition Paul Edmund Strzelecki (1797-1873) arrived in Australia in April 1839, as one of four passengers on the merchant ship Justine carrying potatoes and barley [P1, p. 57]. Half a century had already passed since the British flotilla under the command of Governor Arthur Phillip had landed in Australia on the shores of the Bay, which he named Sydney Harbour, and nearly 70 years since James Cook assimilated Australia into the British Empire. Strzelecki was a passionate of geology, a new discipline at the time, dealing with minerals and the wealth of the earth, and he was an expert in this field. His set goal for visiting Australia was to study Australia’s geology, or at least that of it’s eastern part, which no one had yet done systematically. -

Ecology of Pyrmont Peninsula 1788 - 2008

Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Sydney, 2010. Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula iii Executive summary City Council’s ‘Sustainable Sydney 2030’ initiative ‘is a vision for the sustainable development of the City for the next 20 years and beyond’. It has a largely anthropocentric basis, that is ‘viewing and interpreting everything in terms of human experience and values’(Macquarie Dictionary, 2005). The perspective taken here is that Council’s initiative, vital though it is, should be underpinned by an ecocentric ethic to succeed. This latter was defined by Aldo Leopold in 1949, 60 years ago, as ‘a philosophy that recognizes[sic] that the ecosphere, rather than any individual organism[notably humans] is the source and support of all life and as such advises a holistic and eco-centric approach to government, industry, and individual’(http://dictionary.babylon.com). Some relevant considerations are set out in Part 1: General Introduction. In this report, Pyrmont peninsula - that is the communities of Pyrmont and Ultimo – is considered as a microcosm of the City of Sydney, indeed of urban areas globally. An extensive series of early views of the peninsula are presented to help the reader better visualise this place as it was early in European settlement (Part 2: Early views of Pyrmont peninsula). The physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula has been transformed since European settlement, and Part 3: Physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula describes the geology, soils, topography, shoreline and drainage as they would most likely have appeared to the first Europeans to set foot there. -

New South Wales Topographic Map Catalogue

154° 153° 152° 13 151° 12 150° 149° 148° 147° 28° 146° 145° 144° Coolangatta 143° BEECHMONT BILAMBIL TWEED 9541-4S 9541-1S HEADS 142° Tweed Heads9641-4S WARWICK MOUNT LINDESAY 2014 141° MGA Zone 56 MURWILLUMBAH 2014 2002 1234567891011MGA Zone 55 9341 9441 TWEED KILLARNEY MOUNT 9541 LINDESAY COUGAL TYALGUM HEADS 9641 9341-2N 9441-2N MURWILLUMBAH CUDGEN 9441-3N 9541-3N 9541-2N 9641-3N 2014 2014 2014 2014 Murwillumbah 2013 2002 KOREELAH NP Woodenbong BORDER RANGES NP TWEED ELBOW VALLEY KOREELAH WOODENBONG GREVILLIA 9341-3S 9341-2S BRAYS CREEK BURRINGBAR 28° Index to Major Parks 9441-3S 9441-2S 9541-3S POTTSVILLE 2014 9541-2S 9641-3S 2012 2014 2015 Urbenville 2015 2014 2015 2009 2013 ABERCROMBIE RIVER NP ........ G9 MARYLAND NP TOONUMBAR 2002 2009 THE NIGHTCAP Mullumbimby A BAGO BLUFF NP ...................... D12 WYLIE CREEK TOOLOOM Brunswick Heads SUMMIT CAPEEN NP AFTERLEE NIMBIN BRUNSWICK Boggabilla 9240-1N 9340-4N 9340-1N 9440-4N NP HUONBROOK BALD ROCK NP ......................... A11 9440-1N 9540-4N 9540-1N HEADS BOGGABILLA YELARBON LIMEVALE 2014 2014 BALOWRA SCA ........................... E6 GRADULE BOOMI 2014 2004 2004 2013 Nimbin 9640-4N 8740-N 8840-N 8940-N 9040-N 9140-N KYOGLE 2002 2016 BANYABBA NR .......................... B12 YABBRA NP RICHMOND Kyogle LISMORE BYRON STANTHORPE LISTON PADDYS FLAT Byron Bay BAROOL NP .............................. B12 BONALBORANGE ETTRICK LARNOOK 9240-1S 9340-4S 9340-1S 9440-4S CITY DUNOON BYRON BAY BARRINGTON TOPS NP ........... E11 9440-1S 9540-4S 9540-1S 2014 2014 GOONDIWINDI 2015 YETMAN 2014 TEXAS 2014 2014 2014 NP 9640-4S BURRENBAR BOOMI STANTHORPE DRAKE 2014 2004 2004 2010 BARRINGTON TOPS SCA ....... -

NEWSLETTER Postal: PO Box 15020 City East

The Mineralogical Society of Queensland Inc. NEWSLETTER Postal: PO Box 15020 City East. Brisbane. Qld 4002. Internet: http://www.mineral.org.au Editor: Steve Dobos [email protected] Ph/Fax: (07) 3202 6150 No. 52 August 2008 Office Bearers: 2007-08 President: Russell Kanowski 4635 8627 Vice-President: Ron Young 3807 0870 Secretary: Tony Forsyth 3396 9769 Treasurer: Phil Ericksson 3711 3050 Membership Sec: Bill Kettley 3802 1186 Management Committee: Sue Ericksson 0431 906 769, Theo Kloprogge, George Brabon UPCOMING MINSOCQ MEETINGS 2008 MICROMOB MEETINGS starting 10am Minsoc meetings are held on the last Wednesday of The chosen topic will usually be the morning’s focus, each month, excepting December, at the Mt Gravatt followed by ‘problems’ and swaps in the afternoon …… Lapidary Society clubroom, formally starting at 7.30pm. (The clubhouse is located at the very end of Carson September 13: at the Mt Gravatt Lapidary Society Lane, which is off Logan Road, Upper Mt Gravatt, on Clubroom. The topic will be Pseudomorphs – what they the left as you are heading north towards the city, are and how they occur directly opposite McDonald’s. There is plenty of handy parking available, at no charge). October 11: at the Mt Gravatt Lapidary Society Clubroom. The topic will be Fluorescent Minerals August 27: Annual General Meeting. Reports for the past year will be presented, and new office bearers will November: no meeting due to the Annual Meeting of be elected for the year 2008-2009, plus questions and the Joint Mineralogical Societies of Australia at Zeehan. general discussions. The AGM will be followed by Theo Kloprogge’s presentation, entitled Pseudomorphs – what are they and how do they form? Of course, the Annual Meeting of the Joint Mineralogical Societies ‘minerals’ of the month will be pseudomorphs, so if you of Australia and New Zealand, hosted by the got ‘em, you bring ‘em, please. -

Muelleria Vol 32, 2014

‘A taste for botanic science’: Ferdinand Mueller’s female collectors and the history of Australian botany Sara Maroske Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, South Yarra, Victoria 3141, Australia Abstract Introduction In 1884, Ferdinand Mueller, In 1884, Ferdinand Mueller, Government Botanist of Victoria, told his New Government Botanist of Victoria, South Wales based collector, Mary Bate, ‘You are one of the very few Ladies told his collector Mary Bate that in all Australia, who have any taste for botanic science, in contrast to what she was ‘one of the very few’ women in Australia interested in is observed in all Europe and North America’ (L84.07.20). Mueller made this botany in contrast to the situation remark during a period in the Western world when the study of natural in Europe and North America. history had opened up to the general population, and the study of botany, This proposition is assessed using in particular, was possible for girls and women (Watts 2007). Nevertheless, Maroske and Vaughan’s biographical in opining the relative lack of enthusiasm Australian women had for his register (2014), which identifies 225 of Mueller’s female collectors, favourite science, Mueller was also playing an active part in overcoming it. and outlines their contribution to His letter to Bate was in fact a persuasive, intended to encourage this young Australian botany. An analysis of this woman to remain engaged in what could be an uncomfortable pastime in register reveals that Mueller achieved the bush around Tilba Tilba, by allying her with her more demure flower- a scale and level of engagement pressing and painting sisters at ‘Home’ in the United Kingdom. -

Sherbornia Date of Publication: an Open-Access Journal of Bibliographic 29 March 2021 and Nomenclatural Research in Zoology

E-ISSN 2373-7697 Volume 7(1): 1–4 Sherbornia Date of Publication: An Open-Access Journal of Bibliographic 29 March 2021 and Nomenclatural Research in Zoology Research Note The source of the name of the Sooty Albatross, Phoebetria fusca: a correction Murray D. Bruce P.O. Box 180, Turramurra 2074, NSW, Australia; [email protected] lsid:zoobank.org:pub: 442B27EBF0794BE58FBB65D71B8EB8C8 Karl [or Carl] Theodor Hilsenberg (1802–1824) 787)2. Moreover, another Hilsenbergia already was a young naturalist and collector, principally had been named (Reichenbach 1828: 117) and as a botanist, who died at sea off Île Sainte although later synonymised with Ehretia L., it is Marie (Nosy Boraha), an island off the northeast now recognised as a distinct genus, comprising coast of Madagascar on 11 September 1824 at 21 species in the forgetmenot family Boragi only 22 years of age (Pritzel 1872: 144; Hooker, naceae3. in Hilsenberg & Bojer 1833: 246–247). He had More recently, Hilsenberg’s claim to fame, travelled to Mauritius with his friend and fellow and actually published while he was still active, botanist Wenceslas Bojer (1795–1856), arriving was in naming a new species of albatross, there on 6 July 1821. After spending about a Diomedea fusca (Hilsenberg 1822a: col. 1164). year in Madagascar in 1822–1823, Hilsenberg A short note on his Diomedea fusca, including and Bojer were back at Mauritius. It was during circumscriptive details, also was provided in a a second expedition, departing in 1824, on its periodical usually referred to as ‘Froriep’s Noti- way to the eastern coast of Africa, with Bojer, zen’.