Writings for Acquisition JUN 28 2005 LIBRARIES ROTCH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the 2006 Journal

The Iran Society JOURNAL 2006 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Ta'ziyeh in Iran 4 Alborz Retrospective 11 Architectural conservation in Iran 15 Sadeq Hedayat as a scholar 24 Pascal Coste and Eugene Flandin 29 Abul Ghassem Khan Gharagozlou, Nasser ul-Molk 32 Book Reviews: Eagle's Nest 36 Mirrors of the unseen - Journeys in Iran 38 General Maps of Persia 1477-1925 39 - 2 - INTRODUCTION This has been another busy year for the Society, with a number of well-attended supplementary activities to our usual lecture programme. The Council hopes to build on this over the coming year. In pursuit of the Society’s charitable objects, we are attempting to reach a wider audience than the Society’s present membership. In particular, we are planning a public lecture in memory of Sir Denis Wright, our former president and chairman, who contributed so much to the Society. David Blow, a Council member, is editing a compendium of travellers’ tales on Iran over the ages, which is due to be published by Eland Books next year, and we will continue to arrange tutored visits to UK exhibitions and events connected with Iran. Meanwhile, our Journal continues to go from strength to strength, and we all owe a debt of gratitude to the editor, Antony Wynn, and to Alan Ashmole, who arranges the printing. I am retiring as chairman in October. This is in many ways a sad moment for me, but I am delighted that Hugh Arbuthnott has been elected to succeed me as chairman. As a Persian speaker, who was twice posted to the British Embassy in Tehran and was British Ambassador in three countries, he brings a depth of experience and wisdom which will, I am sure, be of great benefit to the Society. -

''Les Monuments De L'architecture Arabe'

”Les monuments de l’architecture arabe” vus par Pascal Coste Mercedes Volait To cite this version: Mercedes Volait. ”Les monuments de l’architecture arabe” vus par Pascal Coste. Dominique Jacobi. Pascal Coste, toutes les Egypte, Parenthèses/Bibliothèque municipale de Marseille, pp.97-131, 1998. halshs-00957011 HAL Id: halshs-00957011 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00957011 Submitted on 7 Mar 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Mercedes Volait, CNRS "Les monuments de l'architecture arabe" vus par Pascal Coste* (publié in Pascal Coste, toutes les Egypte, sous la direction de Dominique Jacobi, Marseille: Parenthèses/Bibliothèque municipale de Marseille, 1998, p. 97-131) Dans les carnets de dessins que Pascal Coste rapporte en 1827 de ses pérégrinations égyptiennes, "l'architecture arabe" - ainsi qu'il était alors d'usage de la désigner - occupe une place de choix. Certes, cet insatiable curieux et infatigable dessinateur s'est également intéressé à bien d'autres aspects de l'Egypte, qu'il eut l'occasion de parcourir en tous sens au cours de deux longs séjours, le premier effectué d'octobre 1817 à octobre 1822, et le second d'octobre 1823 à novembre 18271: ses albums inédits, qu'il devait léguer à sa ville natale2, sont là pour en témoigner. -

European Artists in Iran During the Qâjâr Period

Mahshid Modares The familiarity of Iranians with European schools of art begins with the political European Artists relationship with Europe in the seventeenth century, and increases in the nineteenth century. in Iran During the In Europe, industrial, social, and cultural changes reformed many political systems in the Qâjâr Period nineteenth century and ended many monarchial, feudal, and hierarchical systems that had existed for centuries. In the transition from monarchy to democracy, according to Stephen Eisenman, in his book Nineteenth Century Art: A Critical History, the bourgeois controlled some parts of Europe for about a century. On the one hand, the working class, farmers, and women followed revolutionary ideas of enlightened individuals in gaining their freedom and equality.1 On the other hand, industrialized nations invaded weak countries in Africa, South America, and the Middle East, maintaining economical and military supremacy during the colonial period of the nineteenth century. Britain, for instance, asserted control over oil and other resources in Iran to assure its routes to India. Countries such as Iran suffered constant interference by Europeans trying to enforce their ascendancy in the name of modernization, two-way friendship, and trade. Having political and economic clout, England, Germany, France, and the United States chased valuable resources and lands. As a part of the plan, European ambassadors, government missions, military men, traders, archeologists, and artists, all of whom traveled to different regions, took back to Europe information on future investments, as well as a large number of ancient and contemporary art pieces and During the Qâjâr epoch Iranian artists exhibited a great treasures, which made many museums and interest in European paintings of the Renaissance and private collections enormously wealthy. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/09/2021 01:46:25PM Via Free Access Guise and Disguise Before and During the Tanzimat 187

chapter 5 Guise and Disguise Before and During the Tanzimat In 1911, French war illustrator Georges Bertin Scott objects coming to life in one’s reminiscence of past de Plagnolle (1873–1943) was entrusted by Henri events is a trope that has already been encoun- Moser with producing colour images for a portfo- tered in the words of artist Fortuny (Chapter 1) lio presenting his Middle Eastern arms and armour and that of architect Baudry (Chapter 4). The arte- displayed at Charlottenfels, the “castle,” or rather facts’ physical arrangements were meant to facili- mansion, which he had bought in Neuhausen tate that process. In his reflections on museology, (Switzerland) and where he had installed a fumoir Lockwood de Forest insisted that the “nearer you arabe [Islamic style smoking room]. Scott brings can get the surroundings which belong with the colour and detail to the type of display favoured objects, the more effective they are.” An enthu- by many collectors throughout the nineteenth siastic supporter of the Musée de Cluny in Paris, century. (Fig. 140) Sets of vibrant draperies and de Forest recalled sitting there on an old bench rugs hang in order to orientalise the armoury. The and feeling the “atmosphere of the Middle Ages.”3 room is replete with artefacts. The plate creates an Dress was an integral part of the method deployed image of plentifulness. Daggers are aligned in glass by private and public collectors alike in order to cases or arranged in mural trophies, while sets of reclaim the past into the present. It had the power armour are worn by papier mâché mannequins. -

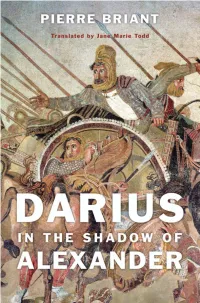

Darius in the Shadow of Alexander

Darius in the Shadow of Alexander DARIUS IN THE SHADOW OF ALEXANDER PIERRE BRIANT TRANSLATED BY JANE MARIE TODD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS LONDON, EN GLAND 2015 Copyright © 2015 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First printing Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the French Ministry of Foreign Aff airs and the Cultural Ser vices of the French Embassy in the United States. First published as Darius dans l’ombre d’Alexandre by Pierre Briant World copyright © Librairie Arthème Fayard, 2003. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Briant, Pierre. [Darius dans l’ombre d’Alexandre. En glish] Darius in the shadow of Alexander / Pierre Briant ; translated by Jane Marie Todd. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 49309- 4 (alkaline paper) 1. Darius III, King of Persia— 330 B.C. 2. Iran— Kings and rulers— Biography. 3. Iran— History—To 640. 4. Alexander, the Great, 356 B.C.– 323 B.C. I. Title. DS284.7.B7513 2015 935'.705092—dc23 [B] 2014018170 Contents Ac know ledg ments vii Preface to the English- Language Edition ix Translator’s Note xvii Introduction: Between Remembering and Forgetting 1 I THE IMPOSSIBLE BIOGRAPHY 1. A Shadow among His Own 15 2. Darius Past and Present 65 II CONTRASTING PORTRAITS 3. “The Last Darius, the One Who Was Defeated by Alexander” 109 4. Arrian’s Darius 130 5. A Diff erent Darius or the Same One? 155 6. Darius between Greece and Rome 202 vi Contents III RELUCTANCE AND ENTHUSIASM 7. -

A Catalogue of Known Gardens in Safavid Iran

A Catalogue of Known Gardens in Safavid Iran Mahvash Alemi* The custom of Iranian kings to move from cool to smaller cities such as Khuy, Shiraz, Kashan, warm places depending on the seasons, hunting Mashhad, Farhabad, Ashraf, and Sari. along the way as well as the need to have different 2. A suburban pleasance garden type defined as residences in different provinces for political reasons bāgh-i shāh (royal garden), bāgh-i takht (throne has led to the creation of a network of gardens in all garden) or chahār bāgh that were great gardens the provinces and along the main communication placed in suburban areas used for the private roads. These gardens can be divided in three main pleasure of the king and his family. Examples types. of this type are the bāgh-i hizār jarīb in Isfahan, 1. An urban type defined as dawlatkhāna (literal- bāgh-i shāh in Shiraz and bāgh-i shāh at Fin ly house of government) that were royal com- near Kashan. A promenade lined with trees plexes consisting of a fabric of courtyards and and watered by water channels called khīyābān gardens that contained the residence for the usually connected the suburban gardens to the king and his family (haram), buildings used urban centre. for official audiencesdivān ( khāna), or the 3. A type of garden created in hunting resorts private audiences of the king (khalvat khāna), by adding small pavilions or water basins to a officesdaftar ( khāna), and services. The latter, natural landscape in the woods or on natural called buyūtāt, consisted of baths (hammām), fountains. -

Ödön Lechner in Context

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Ödön Lechner in Context Studies of the international conference on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Ödön Lechner’s death The publication of this volume was supported by: Magyar Nemzeti Bank Ministry of Human Capacities HUNGARIAN NATIONAL COMMISSION FOR UNESCO Ödön Lechner in Context Studies of the international conference on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Ödön Lechner’s death Edited by Zsombor Jékely with the assistance of Zsuzsa Margittai and Klára Szegzárdy-Csengery Museum of Applied Arts Budapest, 2015 The conference was jointly organized by the Museum of Applied Arts, Budapest and the Institute of Art History, Research Centre for the Humanities, Hungarian Academy of Sciences Organising committee of the conference: Tamás Csáki, András Hadik, Zsombor Jékely, Katalin Keserü, Magda Lichner, József Sisa Edited by Zsombor Jékely with the assistance of Zsuzsa Margittai and Klára Szegzárdy-Csengery English translation: Stephen Kane, Eliška Hulcová, Barbara Lück, Harvey Mendelsohn and the authors Copy editing: Klára Szegzárdy-Csengery Book design: János Lengyel Layout: Zsolt Wilhelem © Museum of Applied Arts, Budapest, 2015 Cover photograph Design for the ceiling in the open atrium of the Museum of Applied Arts, Budapest ISBN 978-615-5217-21-0 Printed and bound by Gyomai Kner Nyomda Zrt., Gyomaendrôd Contents Preface ............................................................................. 7 Overview of the conference and introductions to the sections of the conference ...................... 13 STUDIES Katalin Keserü: The Œuvre of the Architect Ödön Lechner (1845–1914) and Research on Lechner .............. 17 Ilona Sármány-Parsons: Ödön Lechner: Maverick, Dreamer, Patriot – An Architect of Modernisation ........... -

The Architectural Order of Persian Talar Life of a Form

The Architectural Order of Persian Talar Life of a Form Ludovico Micara1 Tout est forme, et la vie même est une forme. Honoré de Balzac La forme … est d’abord une vie mobile dans un monde changeant. Les métamorphoses, sans fin, recommencent. Henri Focillon Abstract: the architectural order of the Persian talar, which characterized the most significant architecture of Safavid Persia and its capital Isfahan in the seventeenth century, condenses within its spaces a series of quality and characteristics that identify it as a recognizable and independent architectural form. This form syncretically collects and expresses a range of experiences and motives, that render the Persian architectural tradition and its continuity during at least 3000 years, an extraordinary unicum. The analysis of the persistence of the talar form to this day highlights the theme of vitality over time of certain architectural shapes and its meaning, whether overt or implied, almost independently of its temporary interpreters; perhaps proving and preluding a possible “life of forms” in architecture. Keywords: Architectural order, Forms, Talar, Hypostyle Hall, Persia, Safavid, Isfahan, Persepolis, the Arab-Islamic Mosque, Gunnar Asplund, Frank Lloyd Wright, Ludovico Quaroni, Norman Foster. The German naturalist, traveler and writer Engelbert Kaempfer, author in 1712 of the “relations, observations and descriptions of Persian things and farther Asia”2, contained in Amoenitatum exoticarum politico- physico-medicarum fasciculi V3, accurately illustrating the palaces and royal gardens of the Safavid Isfahan, avails himself of the opportunity to introduce and describe the talar palace (Fig. 1). Kaempfer distinguishes the two fundamental areas of the palatial structure of Isfahan, and more generally of the courts and royal residences of the Islamic world. -

The Benefits of Historical Studies on Re-Examining the Implemented

arts Article Authenticity and Restoration: The Benefits of Historical Studies on Re-Examining the Implemented Restorations in Persepolis Mahdi Motamedmanesh Institute for Architecture, Technische Universität Berlin (TU Berlin), Straße des 17. Juni 152-Sekr. A 16 10623 Berlin, Germany; [email protected]; Tel.: +49-17680809737; Fax: +49-30-3142-1844 Academic Editor: Aine Mangaoang Received: 24 June 2015; Accepted: 9 February 2016; Published: 4 March 2016 Abstract: Preserving the authenticity of historical monuments is an inseparable part of restoration activities that has always been asserted by the international principles of historical preservation. However, the local condition of historical sites may influence such a primitive intention of restorers. While historical documents are appropriate sources which can provide restorers with the real condition of ancient structures in the course of time, investigation through these precious materials is a time-consuming process and the reliability of these old evidences is, itself, a challenging issue. The Italian Institute for Middle and Far East (IsMEO) missioned long-term restoration activities in Persepolis between 1964 and the Islamic Revolution in Iran. Generally, this institute is praised for this series of projects. In this paper, the author questions the historical authenticity of restoration activities missioned by this institute in a structure so-called The Gate of All Nations. Indeed, the restoration of this structure was influenced by the 2500th anniversary of the Persian Empire, which was held in Persepolis in 1971. By tracing the context of historical evidences and presenting a method for obtaining the authenticity of these documents, this paper demonstrates a new perspective towards the arrangement of a stone-made capital, which ornaments the uppermost part of a re-erected ancient column. -

Herzfeld Symposium, (Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., Mai 2001) ______

À paraître dans : Ann Gunter et Stefan Hauser (éd.), Herzfeld Symposium, (Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., mai 2001) __________________ Milestones in the Development of Achaemenid Historiography in the Times of Ernst Herzfeld (1879-1948) Pierre Briant Collège de France -1- It is clear simply from consulting the bibliography of Ernst Herzfeld that even though he did not confine himself to this time and space of Achaemenid history and archaeology, he published many studies that concerned it. His investigations at Pasargadae, the opening of excavations at Persepolis, the founding of the Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran (the first volume of which was published in 1929-30), the many articles on Achaemenid inscriptions that he published there and elsewhere, and then his book of 1938 on the royal inscriptions--all these are eloquent testimony to his interest in the Iran of the Great Kings. This is surely the reason that the organizers initially asked me to give a presentation on the impact of Herzfeld’s work on Achaemenid history. Nevertheless, after consulting with Ann Gunter and Stefan Hauser, I decided to modify my approach somewhat1. In the first place, it is essential to recall that Herzfeld was at once a linguist, an epigraphist, an archaeologist, a historian of art, a geographer, and more, as is revealed particularly well by his work at Pasargadae, where he marshalled every kind of information that was available then (almost a century ago), and where he opened radically new perspectives. It was the same at Persepolis between 1931 and 1934, after the remarkable bilingual report published in 1929-30, in French and Persian (AMI 1: 17-40). -

The Tiered Stages of Naqsh-I Jahan Square in Isfahan

Empire In-the-Round: The Tiered Stages of Naqsh-I Jahan Square in Isfahan Sean P. Silvia University of Southern California “They say Isfahan is ‘Half the World’ By saying this, they only describe half of Isfahan” - Iskandar Munshi (Translated by Stephen P. Blake) Introduction Scholars have identified an iconographic connection between the Safavid maydan (city square) and the theater,1 the Safavid coffeehouse and the theater,2 and the caravanserai (inn for travelers) as an origin point for Safavid theater architecture.3 It is noteworthy that all of these types of theatrical structures are present within Naqsh-i Jahan Square in the Safavid’s capital city of Isfahan, a building complex known for its architectural unity (Fig.1),4 and all 1 Sussan Babaie, Kathryn Babayan, Massumeh Farhad, Ina Baghdiantz-McCabe, and Christoph Werner, Slaves of the Shah: New Elites of Safavid Iran, (London: Touris, 2004), 85; Babak Rahimi, “Maydān-I Naqsh-I Jahān: The Safavid Isfahan Public Square as “A Playing Field”, in In the Presence of Power: Court and Performance in the Pre-Modern Middle East, edited by Pomerantz Maurice A. and Vitz Evelyn Birge, 42-60, (New York: NYU Press, 2017). 2 Farshid Emami, “Coffeehouses, Urban Spaces, and the Formation of a Public Sphere in Safavid Isfahan,” Muqarnas Online 33, no. 1 (November 2016): 177-220, 191. 3 Jamshid Malekpour, The Islamic Drama, (London: Taylor a& Francis Group, 2004), 111. 4 “Isfahan,” in The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, edited by Jonathan M. Bloom, Sheila S. Blair. http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t276/e25; Sheila S. -

Augustus, the King of Kings

(RE)PRESENTING EMPIRE: THE ROMAN IMPERIAL CULT IN ASIA MINOR, 31 BC – AD 68 by Benjamin B. Rubin A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in the University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elaine K. Gazda, Co-Chair Professor Margaret C. Root, Co-Chair Professor Janet E. Richards Professor Carla M. Sinopoli © Benjamin B. Rubin All rights reserved 2008 For Lyndell. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want express my sincerest gratitude to all those who have helped to make this dissertation possible. My co-chairs, Elaine Gazda and Margaret Cool Root, have shown support for my project since its inception. I am indebted to them for their kindness, patience and thoughtful criticism of my written work. I would like to thank Elaine Gazda for instilling in me a careful attention to detail, which has helped me to clarify both my thinking and my writing. Her boundless energy and enthusiasm have been a continual inspiration to me over the past seven years. I greatly benefited from her eminar on the cities of Roman Asia Minor and the subsequent trip she organized to Turkey during the summer of 2004. I am grateful to Margaret Cool Root for encouraging me to think broadly and make connections across disciplinary divides. She has given me the courage to challenge my most deeply held assumptions and to share my ideas with the world. I admire Margaret not only for her scholarly acumen, but also for her deep commitment to cause of social justice both in the classroom and society at large.